Cheetahs, with their sleek bodies and distinctive spotted coats, have captivated human imagination for centuries. As the fastest land animals on Earth, these magnificent big cats are often surrounded by myths and misconceptions that have persisted through time. While cheetahs are among the most recognized wild animals globally, many commonly held beliefs about them simply don’t align with scientific reality. From their hunting abilities to their relationship with humans, numerous falsehoods have taken root in popular culture.

In this article, we’ll separate fact from fiction by examining ten widespread myths about cheetahs and providing the scientific evidence that debunks them. By understanding the true nature of these remarkable creatures, we can better appreciate their unique adaptations and the conservation challenges they face in the wild. Let’s dive into the fascinating world of cheetahs and discover what science really tells us about these extraordinary big cats.

Myth 10 Cheetahs Are the Same as Leopards

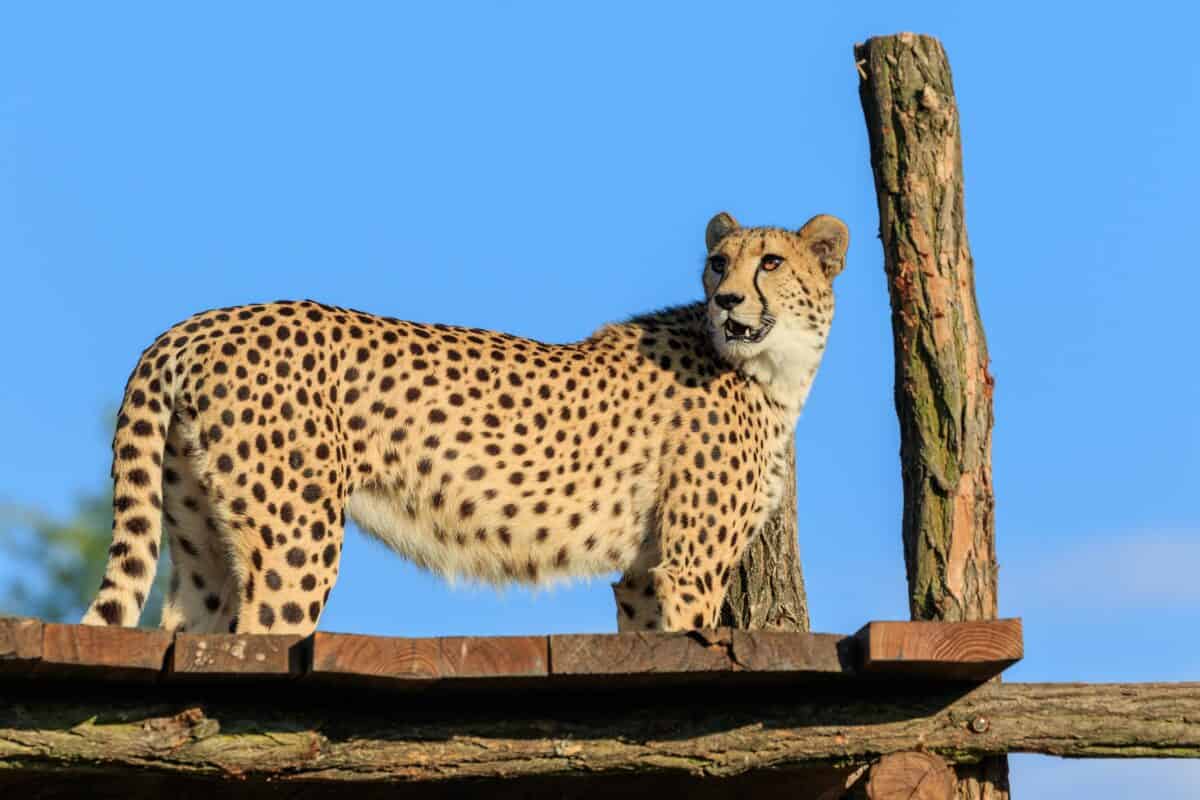

One of the most common misconceptions is that cheetahs and leopards are either the same species or nearly identical. While both are spotted big cats native to Africa, they are distinct species with significant differences. Cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) have a slender build optimized for speed, with solid black spots, distinctive “tear marks” running from the corners of their eyes to their mouths, and smaller heads relative to their bodies. Their claws are only semi-retractable, a specialization that provides better traction when running at high speeds.

Leopards (Panthera pardus), by contrast, are more powerfully built with rosette-shaped spots rather than solid dots. They have fully retractable claws, larger and more muscular heads, and lack the facial tear marks of cheetahs. Genetically, they’re even more different—leopards belong to the genus Panthera alongside lions, tigers, and jaguars, while cheetahs are the only living member of the genus Acinonyx. Scientists estimate these species diverged evolutionarily approximately 6.7 million years ago, making them about as related as humans are to some monkey species.

Myth 9 Cheetahs Are the Most Dangerous Big Cats

Many people mistakenly believe that cheetahs pose a significant threat to humans, lumping them together with other big cats as dangerous predators. Scientific evidence tells a very different story. Cheetahs are actually among the least dangerous of the big cats to humans. Their physical structure is specialized for speed rather than power, with a lightweight frame that would be damaged in confrontations with larger animals. Unlike lions or tigers, cheetahs have small jaws and teeth relative to their size, limiting their bite force.

Historical records of cheetah attacks on humans are exceedingly rare, with virtually no documented fatalities in the wild. This non-aggressive nature toward humans helps explain why cheetahs were kept as hunting companions by royalty in ancient Persia, India, and Egypt—a relationship that would have been impossible with more aggressive big cats. Conservation experts who work closely with cheetahs consistently report that while still wild animals deserving respect, they are typically shy and avoid human contact rather than seeking confrontation. Their natural instinct when threatened is to flee rather than fight.

Myth 8 Cheetahs Can Maintain Top Speed for Long Periods

The cheetah’s incredible speed—up to 70 mph (113 km/h)—is well-documented and accurate. However, a persistent myth suggests they can maintain these blazing speeds for extended periods, racing across vast distances at full sprint. Scientific studies using GPS tracking collars and high-speed cameras have revealed the truth: cheetahs can only maintain their top speed for approximately 20-30 seconds before overheating becomes dangerous. Most chases last even less time, typically between 10-20 seconds and covering distances of 200-300 meters (656-984 feet).

The physiological limitations are clear—a cheetah’s body temperature can rise from 38°C (100.4°F) to 40.5°C (105°F) during a chase, requiring a recovery period of about 30-40 minutes before they can run again. Their respiratory rate increases from 60 to 150 breaths per minute during pursuit. Rather than running marathons, cheetahs are evolutionary sprinters, with specialized adaptations including an enlarged heart, oversized lungs, wide nostrils, and expanded sinuses that collectively support oxygen intake during brief, explosive bursts of speed. After these short chases, they must rest regardless of the hunt’s outcome, making their hunting strategy one of short-distance ambush rather than long-distance pursuit.

Myth 7 Cheetahs Roar Like Other Big Cats

A common misconception places cheetahs alongside lions, tigers, leopards, and jaguars as roaring big cats. However, zoologists classify big cats into two distinct categories: those that can roar (genus Panthera) and those that cannot. Cheetahs fall firmly in the latter group. The anatomical reason is fascinating—cheetahs have a fixed hyoid bone in their throat, unlike the flexible hyoid bone of true roaring cats. This structural difference physically prevents them from producing the deep, intimidating roar associated with lions or tigers.

Instead, cheetahs communicate through a remarkable range of other vocalizations. Their most distinctive sound is a high-pitched chirp or yelp that sounds more like a bird call than a traditional cat sound. They also purr loudly when content (both while exhaling and inhaling, unlike domestic cats), and can hiss, growl, and make a unique “stuttering” vocalization during courtship. Some cheetahs even produce a “bleat” sound similar to that of goats. These vocalizations, particularly the chirping, serve crucial functions in communication between mothers and cubs and between coalition members, helping these social cats coordinate while maintaining visual contact in tall grasslands.

Myth 6 Cheetahs Are Solitary Like Most Cats

Many assume cheetahs are solitary animals like most other felids, interacting only for mating purposes. This generalization significantly misrepresents cheetah social behavior, which varies considerably by sex and circumstance. Adult female cheetahs do typically live solitary lives except when raising cubs, which stay with their mother for 13-20 months learning hunting and survival skills. However, male cheetahs display a social complexity that defies the solitary stereotype entirely. Approximately 60% of male cheetahs live in small groups called coalitions, usually consisting of 2-4 individuals, often but not always brothers from the same litter.

These coalitions are remarkably stable, with members hunting together, defending territories collectively, and sometimes even cooperating to court females—though only one male typically mates. Research by the Cheetah Conservation Fund and other organizations has documented coalitions lasting the entire adult lifespan of the members, with strong social bonds demonstrated through grooming, coordinated territorial patrolling, and shared hunting success. This social structure gives coalition males significant advantages, allowing them to defend larger territories and achieve higher reproductive success than solitary males. The complex social dynamics of cheetahs align them more closely with lions (the only truly social big cats) than with solitary species like tigers or leopards.

Myth 5 Cheetahs Always Lose Their Kills to Larger Predators

A widespread belief suggests that cheetahs invariably lose their hard-won meals to larger predators like lions and hyenas—sometimes portrayed as happening nearly 100% of the time. While kleptoparasitism (food theft) is indeed a challenge for cheetahs, scientific field studies present a more nuanced reality. Research from the Serengeti indicates that cheetahs lose approximately 10-15% of their kills to other predators, not the majority as often claimed. In the Kalahari, this figure ranges between 20-25%, depending on the density of other large carnivores in the area.

Cheetahs have developed strategic adaptations to minimize kill losses. They typically hunt during daylight hours when lions are least active, often choosing early morning or late afternoon. Once a kill is made, they eat rapidly, consuming up to 14 kg (31 pounds) of meat in one sitting—approximately 20% of their body weight. Research from Namibia’s cheetah populations shows they preferentially hunt in areas with good visibility, allowing them to spot approaching competitors and make strategic decisions about whether to defend their kill or abandon it to avoid injury. Far from being perpetual victims, cheetahs have evolved behavioral strategies that allow them to maintain sufficient caloric intake despite competition from larger predators in their ecosystem.

Myth 4 Cheetahs Are Unsuccessful Hunters

A persistent myth portrays cheetahs as inefficient hunters with dismal success rates, sometimes claimed to be as low as 5-10%. This misconception likely stems from comparing isolated hunting statistics across different predator species without accounting for their hunting strategies. In reality, comprehensive field research conducted over decades tells a different story. Studies in the Serengeti have documented cheetah hunting success rates between 50-70%, making them among the most successful mammalian predators. For comparison, lions typically succeed in 25-30% of hunts, and leopards in 38-40%.

The variation in reported success rates can be explained by several factors, including prey type, habitat, season, and observation methodology. Cheetahs are particularly successful when hunting smaller antelopes like Thomson’s gazelles and impala, especially when targeting young or old individuals. Their success rates decrease when pursuing larger or more vigilant prey. Additionally, researchers now recognize that using different definitions of what constitutes a “hunt attempt” significantly affects reported success rates. When standardized measurement protocols are applied, cheetahs consistently demonstrate high hunting efficiency, especially considering they hunt alone or in small groups rather than in the larger prides that benefit lions. Their exceptional speed, acceleration, and maneuverability—combined with calculated prey selection—make them formidable hunters despite their relatively small size among big cats.

Myth 3 Cheetahs Cannot Climb Trees

A common misconception holds that cheetahs, unlike other big cats, are incapable of climbing trees due to their specialized running adaptations—particularly their semi-retractable claws. While cheetahs are indeed less proficient climbers than leopards (renowned for hauling large prey up trees) and don’t regularly climb as part of their hunting strategy, zoological research confirms they absolutely can and do climb trees. Field researchers have documented wild cheetahs climbing trees for various purposes, including using elevated positions as vantage points for spotting prey and potential threats.

Their climbing ability is particularly evident in cubs and adolescents, who frequently climb as part of play and skills development. Adult cheetahs have been photographed resting on lower, accessible branches in areas where suitable trees are available. Their semi-retractable claws, while specialized for traction during high-speed running, still provide adequate grip for climbing when necessary. The Cheetah Conservation Fund and other research organizations have observed that climbing behavior varies significantly between individual cheetahs and between populations in different habitats, suggesting this behavior has both genetic and learned components. While climbing is not their primary adaptation or preferred activity, the absolute statement that cheetahs “cannot climb trees” is scientifically inaccurate.

Myth 2 Cheetahs Are Simply Smaller Versions of Ancient Cheetahs

Many assume modern cheetahs are merely smaller versions of their prehistoric ancestors, but paleontological evidence reveals a fascinating evolutionary history far more complex than simple downsizing. The modern cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) is actually the last surviving member of a once diverse subfamily, Acinonychinae, that included several genera and species adapted for cursorial (running) hunting. The giant cheetah (Acinonyx pardinensis), which lived approximately 3 million to 500,000 years ago, stood significantly taller than modern cheetahs with a shoulder height approaching 3 feet and an estimated weight of 79-143 kg (174-315 pounds)—nearly twice the size of today’s cheetahs.

Perhaps more surprising, genetic analysis reveals modern cheetahs underwent a severe population bottleneck approximately 10,000-12,000 years ago, coinciding with the end of the last ice age. This event reduced genetic diversity so dramatically that modern cheetahs show less genetic variation between individuals than exists between identical twins in humans. This genetic uniformity, rather than representing a simple continuation of ancient lineages, demonstrates that today’s cheetahs survived a near-extinction event that eliminated many other cheetah species and genetically distinct populations. The modern cheetah represents not a downsized version of its ancestors, but rather a highly specialized survivor that narrowly escaped extinction during a period of massive ecological change—a history written clearly in their genetics and the fossil record.

Myth 1 Captive Cheetahs Cannot Be Released Into the Wild

A widespread belief suggests that once cheetahs have been in captivity, they can never successfully return to the wild due to dependency on humans or loss of hunting skills. While reintroduction is indeed challenging, scientific evidence from multiple conservation programs demonstrates it is possible with proper protocols. Organizations like the Cheetah Conservation Fund in Namibia have developed successful rehabilitation techniques that include minimizing human contact, providing opportunities to develop and maintain hunting skills, and implementing gradual “soft release” programs where cheetahs transition through progressively more natural environments before full release.

Success rates vary based on multiple factors, including the age at which cheetahs entered captivity, the duration of captivity, the methods used during rehabilitation, and the quality of the release habitat. Orphaned cubs raised in specialized facilities with minimal human imprinting show particularly promising results, with some programs documenting post-release survival rates of 70% or higher at the one-year mark. GPS collar tracking of released cheetahs has shown many successfully establish territories, hunt effectively, and even reproduce in the wild. While not every captive cheetah is a candidate for release, and the process requires significant resources and expertise, the absolute claim that captive cheetahs “cannot” return to the wild has been scientifically disproven through multiple successful reintroduction programs across Africa.

Why These Myths Matter Conservation Implications

The myths surrounding cheetahs aren’t merely harmless misconceptions—they have tangible impacts on conservation efforts for this vulnerable species. When cheetahs are confused with leopards or incorrectly perceived as dangerous to humans, it can affect public policy decisions about habitat protection and human-wildlife conflict resolution. Misunderstandings about their social behavior and hunting effectiveness can lead to improper management strategies that don’t account for their actual ecological needs. With fewer than 7,000 cheetahs remaining in the wild, precision in our understanding has never been more critical.

Scientific literacy about cheetahs directly translates to more effective conservation. For example, recognizing their true success rate as hunters helps explain why habitat fragmentation is so devastating—cheetahs require sufficient space and prey density to maintain their energy balance. Understanding their genetic bottleneck and limited diversity helps explain their reproductive challenges and vulnerability to disease. As climate change and human development continue to threaten cheetah populations, correcting these myths provides a foundation for evidence-based conservation. By replacing misconceptions with scientific reality, we not only appreciate these remarkable animals more fully but also enhance our ability to ensure their survival for future generations.

Conclusion: Separating Cheetah Fact from Fiction

Throughout this article, we’ve examined ten persistent myths about cheetahs and replaced them with scientific evidence that reveals these remarkable animals in their true light. From their distinctive evolutionary path separate from other big cats to their complex social structures and impressive hunting prowess, cheetahs are far more nuanced and fascinating than popular misconceptions suggest. By understanding their actual biological limitations—like their brief sprint capacity and challenges with genetic diversity—we gain appreciation for the remarkable adaptations that have allowed them to survive in challenging environments.

These scientific clarifications matter beyond mere zoological curiosity. Cheetahs face significant conservation challenges, with population declines of over 90% in the past century reducing their range to just 9% of their historical territory. Accurate information forms the foundation of effective protection strategies,

- 14 Spiders That Are Surprisingly Smart - August 14, 2025

- 10 Myths About Cheetahs Busted by Science - August 14, 2025

- 10 Hiking Trails with Most Mountain Lion Sightings in the United States - August 14, 2025