The Pacific Islands, with their isolated nature and diverse ecosystems, have become evolutionary hotspots for unique wildlife found nowhere else on Earth. These islands, scattered across the vast Pacific Ocean, have allowed species to evolve in isolation, developing extraordinary adaptations and characteristics. From flightless birds to giant fruit bats, the endemic creatures of the Pacific Islands represent some of nature’s most fascinating evolutionary experiments. In this article, we’ll explore ten remarkable animals that call these remote paradises home, showcasing the biological treasures that make conservation of these island ecosystems so crucial.

11. The Kagu: New Caledonia’s Ghost Bird

The Kagu (Rhynochetos jubatus) is perhaps one of the most distinctive birds of the Pacific, found exclusively on the island of New Caledonia. Often called the “ghost bird” due to its almost entirely white plumage, this flightless bird stands about 55 centimeters tall and possesses a striking crest that it raises when alarmed. The Kagu evolved in the absence of mammalian predators, which explains its ground-dwelling lifestyle and limited flying abilities. What makes the Kagu particularly remarkable is its evolutionary uniqueness—it’s the sole surviving member of the family Rhynochetidae, representing a lineage that has evolved separately from other birds for millions of years.

Unfortunately, the Kagu faces severe threats from introduced predators like cats, dogs, and rats. Conservation efforts have been implemented in recent decades, including protected areas and breeding programs, which have helped stabilize the population. Currently classified as endangered, the Kagu population is estimated at fewer than 1,500 individuals in the wild, making it one of the Pacific’s most precious living treasures.

10. The Fijian Crested Iguana: A Living Jewel

The Fijian Crested Iguana (Brachylophus vitiensis) is a striking emerald-green reptile adorned with distinctive white bands and an impressive dorsal crest of spines. Found only on a few small islands in the Fiji archipelago, this magnificent lizard has become one of the most recognizable symbols of Fijian wildlife. Growing up to 75 centimeters in length, these iguanas spend most of their time in the forest canopy, feeding primarily on leaves, flowers, and fruits of native plants.

The Fijian Crested Iguana represents an extraordinary evolutionary story. Scientists believe that the ancestors of these iguanas floated on debris across thousands of kilometers of ocean from the Americas to reach Fiji millions of years ago. Today, the species is critically endangered, with fewer than 5,000 individuals remaining in the wild. Habitat destruction, introduced predators, and competition from goats for food resources have all contributed to their decline. Conservation efforts include protected reserves on several small islands and captive breeding programs in international zoos.

9. Samoan Flying Fox: The Giant Fruit Bat

The Samoan Flying Fox (Pteropus samoensis) is one of the largest bats in the world, with a wingspan that can reach up to 1.5 meters. Endemic to the Samoan Archipelago and Fiji, these magnificent creatures are sometimes called “flying foxes” due to their fox-like faces and large size. Unlike most bat species, the Samoan Flying Fox is diurnal, actively foraging during daylight hours, which makes it more visible to humans than many other bat species.

These bats play a crucial ecological role as seed dispersers and pollinators, helping to maintain the health and diversity of native forests. They feed primarily on fruits, flowers, and nectar from various plants, including many species that have co-evolved with the bats over millions of years. Some plant species in Samoa depend almost exclusively on these flying foxes for pollination or seed dispersal. Despite their ecological importance, Samoan Flying Foxes face multiple threats, including habitat loss, hunting for food, and vulnerability to tropical cyclones that can devastate entire colonies. Current conservation efforts focus on habitat protection and education programs to reduce hunting pressure.

8. Palau Fruit Dove: A Living Rainbow

The Palau Fruit Dove (Ptilinopus pelewensis) represents nature’s artistic prowess at its finest. This small, colorful bird is endemic to the Palau archipelago in Micronesia and displays a stunning palette of colors that seems almost unreal. Their plumage features a bright green back, a crimson crown, a brilliant yellow breast, and a purple belly patch—making them one of the most vibrantly colored birds in the Pacific. Measuring only about 20-22 centimeters in length, these doves are as small as they are spectacular.

Palau Fruit Doves inhabit tropical forests, where they feed primarily on fruits and berries. Their specialized diet makes them important seed dispersers for many native tree species. Unlike many other Pacific island birds, the Palau Fruit Dove has maintained relatively stable populations, though habitat loss remains a concern. Their vibrant colors evolved as a form of species recognition in the dense forest canopy rather than for camouflage. Interestingly, these doves have a distinctive and melodious cooing call that echoes through the forests of Palau, adding an auditory dimension to their already remarkable presence.

7. New Guinea’s Ribbon-tailed Astrapia: The Bird of Paradise

The Ribbon-tailed Astrapia (Astrapia mayeri) is one of the most extraordinary members of the bird-of-paradise family, found exclusively in the high mountain forests of Papua New Guinea. What makes this bird truly remarkable is the male’s tail feathers, which can grow up to three times the length of its body, reaching an astonishing one meter in length. These white, ribbon-like tail streamers are the longest tail feathers in relation to body size of any bird species in the world. As the bird flies through the forest, these elegant streamers trail behind like flowing ribbons, creating one of nature’s most spectacular displays.

Discovered relatively recently in 1938, the Ribbon-tailed Astrapia lives in remote cloud forests at elevations between 2,500 and 3,500 meters. Males perform elaborate courtship displays, showcasing their extraordinary tails to attract females. The species faces threats from habitat loss due to logging and human encroachment, as well as hunting for their magnificent feathers, which are prized for ceremonial headdresses by local tribes. Conservation efforts include the establishment of protected areas and work with indigenous communities to develop sustainable alternatives to traditional hunting practices.

6. Tuatara: The Living Fossil of New Zealand

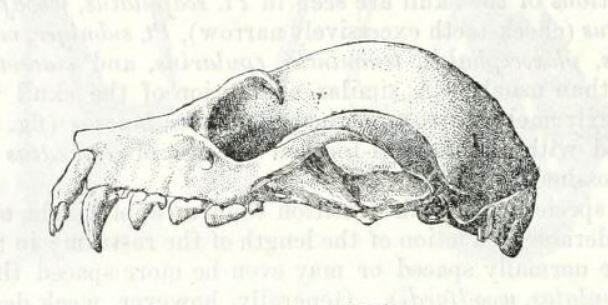

The Tuatara (Sphenodon punctatus) is perhaps one of the most remarkable reptiles on Earth, often called a “living fossil” because it is the sole survivor of an ancient reptile order that flourished during the age of dinosaurs over 200 million years ago. Endemic to New Zealand, these lizard-like creatures are not actually lizards at all but the last representatives of the order Rhynchocephalia, which disappeared everywhere else in the world. The Tuatara possesses several unique features, including a third eye (a light-sensitive organ on the top of its head), teeth fused directly to its jawbone, and the ability to live well over 100 years.

Tuataras are slow-growing, slow-reproducing animals with a remarkably slow metabolism that allows them to remain active at temperatures as low as 5°C (41°F), much colder than most reptiles can tolerate. Females lay eggs only once every 2-5 years, and these take 11-16 months to hatch—the longest incubation period of any reptile. Once widespread across New Zealand’s main islands, Tuataras now survive primarily on about 30 small offshore islands where introduced predators have been eliminated. Conservation programs, including captive breeding and reintroduction efforts, are helping to ensure the survival of this evolutionary treasure, which provides scientists with a living window into the distant past.

5. Hawai’i’s Happy Face Spider: Nature’s Emoji

The Happy Face Spider (Theridion grallator), found only in the Hawaiian archipelago, represents one of nature’s most whimsical creations. This tiny arachnid, measuring just 5 millimeters across, has gained fame for the distinctive marking on its abdomen that remarkably resembles a smiling face. The yellow abdomen typically features a pattern of black markings that form what appears to be two eyes and a smile, though the patterns vary significantly between individuals. Some spiders display perfectly clear “smiley faces,” while others show more abstract patterns that may resemble frowns, grimaces, or no face at all.

This spider exhibits an extraordinary form of genetic polymorphism, with over 20 distinct color patterns documented among populations. Scientists believe this variation may have evolved as a defense mechanism against predators, as birds may not recognize different color morphs as the same prey item. Found in native Hawaiian rainforests at elevations between 1,000 and 2,300 meters, these spiders face threats from habitat loss and introduced species. They typically live on the undersides of leaves, where they construct small webs to catch tiny insects. The Happy Face Spider represents just one example of the unique evolutionary paths taken by species in the isolated Hawaiian Islands, where approximately 99% of native terrestrial arthropods are endemic.

4. Solomon Islands Skink: The Giant Forest Lizard

The Solomon Islands Skink (Corucia zebrata), also known as the Prehensile-tailed Skink or Monkey-tailed Skink, holds the distinction of being the world’s largest skink species. This remarkable reptile, found exclusively in the Solomon Islands archipelago, can grow up to 72 centimeters (28 inches) in length, with nearly half of that being its powerful, prehensile tail. Unlike most reptiles, which are solitary, these skinks exhibit complex social behaviors, living in family groups of up to 35 individuals that share territories, food resources, and participate in communal care of offspring.

What makes the Solomon Islands Skink truly unique among reptiles is its herbivorous diet—it feeds primarily on leaves, flowers, and fruits—and its reproductive strategy. Rather than laying eggs like most skinks, females give birth to a single, well-developed live young after a gestation period of 6-8 months. The newborn skink is remarkably large, typically about one-third the size of its mother. These skinks are arboreal, spending most of their lives in the forest canopy, where they use their strong, prehensile tails to grasp branches while climbing. Unfortunately, habitat destruction and the illegal pet trade have placed significant pressure on wild populations, leading to concerns about their long-term survival.

3. Tongan Megapode: The Volcanic Incubator

The Tongan Megapode (Megapodius pritchardii), locally known as the Malau, employs one of the most unusual reproductive strategies in the bird world. Endemic to the small island of Niuafo’ou in the Kingdom of Tonga, this chicken-sized bird does not incubate its eggs by sitting on them like most birds. Instead, it buries its eggs in volcanically heated soil or sand near active volcanic vents, using the geothermal heat to incubate them. This remarkable adaptation allows parent birds to lay their eggs and then abandon them, leaving the volcanic heat to do the work of incubation.

The Tongan Megapode lays unusually large eggs relative to its body size—each egg weighs approximately 10% of the female’s body weight. After hatching, the chicks must dig their way up through 30-40 centimeters of soil without any parental assistance. Remarkably, they emerge fully feathered and capable of flying almost immediately, an adaptation necessary for survival without parental care. With fewer than 1,500 individuals remaining in the wild, the Tongan Megapode is classified as endangered. Conservation challenges include egg harvesting by local communities (a traditional practice), habitat destruction, and the introduction of predators like cats and rats. Recent conservation efforts focus on establishing protected nesting grounds and educating local communities about sustainable egg harvesting practices.

2. Fiji’s Crested Iguana: The Rainbow Lizard

The Fiji Banded Iguana (Brachylophus fasciatus) is one of the most visually striking reptiles in the Pacific Islands, recognized for its brilliant emerald green coloration adorned with vertical white or light blue bands. These arboreal lizards, reaching lengths of up to 60 centimeters, possess a small crest of spines running down their back that males can raise during territorial displays or courtship rituals. What makes these iguanas particularly remarkable is their evolutionary history—they are descended from iguana ancestors that somehow made the 8,000-kilometer journey from South or Central America to Fiji millions of years ago, likely drifting on vegetation rafts across the vast Pacific Ocean.

Fiji Banded Iguanas are strictly herbivorous, feeding on the leaves, fruits, and flowers of native Fijian plants. They have specialized adaptations for their arboreal lifestyle, including strong claws for climbing and a prehensile tail that provides balance and support. Unlike many lizards that can shed and regrow their tails, these iguanas cannot regenerate a lost tail. During breeding season, females lay 3-6 eggs in shallow burrows in the soil, which incubate for about three months before hatching. Due to habitat loss, introduced predators (particularly cats and mongooses), and competition from invasive species, the Fiji Banded Iguana is now critically endangered, with small populations persisting on just a handful of islands. Conservation programs include captive breeding efforts and habitat restoration on predator-free islands.

1. Vanuatu Flying Fox: The Island’s Ecological Keystone

The Vanuatu Flying Fox (Pteropus anetianus) is a species of fruit bat endemic to the Vanuatu archipelago in the South Pacific. With a wingspan of up to 1.2 meters, these large bats are an impressive sight as they navigate the tropical forests of their island home. Unlike insectivorous bats that use echolocation, flying foxes rely primarily on their excellent eyesight and sense of smell to locate food. Their diet consists primarily of fruits, flowers, and nectar, making them crucial pollinators and seed dispersers for many native plant species. Some plants have even evolved to produce flowers and fruits specifically adapted to attract these flying mammals.

Vanuatu Flying Foxes play a vital ecological role as “forest gardeners,” helping to maintain the health and diversity of island ecosystems. When they consume fruits, they either disperse the seeds through their droppings or drop partially eaten fruits as they feed, helping to spread plant species across the landscape. Many large-seeded plant species depend almost exclusively on flying foxes for seed dispersal, as other animals cannot swallow or transport such large seeds. Unfortunately, these bats face multiple threats, including habitat loss due to deforestation, hunting for food (they are considered a delicacy in traditional cuisine), and vulnerability to climate change impacts such as increasingly powerful cyclones. Conservation efforts focus on establishing protected areas, implementing sustainable hunting practices, and educating local communities about the ecological importance of these remarkable flying mammals.

The incredible animals found exclusively in the Pacific Islands represent millions of years of evolutionary experimentation, resulting in some of the world’s most unique and specialized creatures. These endemic species have evolved in isolation, developing remarkable adaptations and filling ecological niches that don’t exist elsewhere. Their presence tells the story of how life can develop along extraordinary paths when given enough time and isolation. From the third eye of the Tuatara to the volcanic incubation of the Tongan Megapode, these animals showcase nature’s endless capacity for innovation and adaptation.

Unfortunately, many of these irreplaceable species now face existential threats. Island species are particularly vulnerable to extinction, with limited ranges and often no evolutionary experience with mammalian predators or human disturbance. Conservation efforts throughout the Pacific Islands are working to preserve these living treasures through protected areas, breeding programs, predator control, and community education. The future of these remarkable animals depends on our recognition of their value—not just as curiosities, but as essential components of unique island ecosystems and as windows into evolutionary processes that have shaped life on our planet.

- 11 Incredible Animals Found Only in the Pacific Islands - August 9, 2025

- Why Zebras Roll in Dust and Mud - August 9, 2025

- America’s Most Endangered Mammals And How to Help - August 9, 2025