The vast expanse of our oceans harbors some of the most magnificent creatures on Earth, many of which dwarf even our maritime vessels. These colossal marine inhabitants remind us of nature’s awe-inspiring scale and our relative smallness in the grand scheme of the natural world. From ancient leviathans that have cruised the depths for millions of years to modern giants that continue to mystify scientists, the ocean’s largest residents showcase remarkable adaptations for life in the deep. This article explores fourteen extraordinary ocean creatures that exceed boats in size, revealing fascinating insights about their biology, behavior, and the challenges they face in today’s changing marine environments.

The Blue Whale Earth’s Largest Creature

The blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus) stands undisputed as the largest animal ever to have existed on Earth, surpassing even the most massive dinosaurs. Reaching lengths of up to 100 feet (30 meters) and weighing as much as 200 tons, these magnificent mammals easily dwarf many fishing vessels and recreational boats. A blue whale’s tongue alone can weigh as much as an elephant, and its heart is comparable in size to a small car. Despite their immense size, blue whales feed almost exclusively on tiny krill, consuming up to 4 tons of these small crustaceans daily during feeding season. Their size exceeds not just small vessels but even medium-sized boats, with some mature specimens growing longer than traditional whale-watching vessels that seek them out. Currently listed as endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), blue whale populations are slowly recovering after being decimated by commercial whaling in the 20th century.

Fin Whale The Greyhound of the Sea

Often referred to as the “greyhound of the sea” due to its sleek build and impressive speed, the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) is the second-largest animal on Earth after the blue whale. These magnificent creatures can grow to lengths of 85 feet (26 meters) and weigh up to 80 tons, exceeding the size of most fishing trawlers and recreational yachts. With their distinctive asymmetrical coloration—the right side of their jaw is white while the left is black—fin whales are unique among baleen whales. They can accelerate to speeds of 25-30 mph (40-45 km/h), making them among the fastest of all cetaceans. A fin whale’s powerful tail can create waves large enough to rock boats that venture too close. Despite their massive presence in our oceans, these giants face significant threats from vessel strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and the ongoing impacts of climate change on their prey availability.

The Colossal Squid Deep-Sea Mystery

The colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni) remains one of the ocean’s most enigmatic inhabitants, with much of its life cycle and behavior still unknown to science. Found in the deep waters of the Antarctic Ocean, these enormous cephalopods can reach estimated lengths of 45-50 feet (14-15 meters), including their tentacles, making them longer than many small to medium-sized boats. The largest scientifically documented specimen weighed approximately 1,100 pounds (500 kg), though many scientists believe larger individuals exist in the unexplored depths. Unlike the giant squid, the colossal squid has a more massive body with shorter tentacles equipped with sharp, swiveling hooks and the largest eyes in the animal kingdom—measuring up to 11 inches (28 cm) in diameter. These enormous eyes allow them to detect the faintest light in the darkest ocean depths. While rarely encountered by humans due to their deep-sea habitat, their sheer size would make them formidable alongside many research vessels that study the Antarctic waters.

Sperm Whale The Ocean’s Deep Diver

Made famous by Herman Melville’s novel “Moby Dick,” the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) is the largest toothed predator on Earth and one of the ocean’s most impressive deep divers. Males can grow to lengths of 60-65 feet (18-20 meters) and weigh up to 57 tons, easily overshadowing fishing boats and small yachts. Their most distinctive feature is their massive, block-shaped head, which contains the largest brain of any animal on Earth and a specialized organ called the spermaceti organ. This unique structure, filled with a waxy substance once highly prized by whalers, helps regulate buoyancy during their remarkable dives. Sperm whales routinely descend to depths of 3,280 feet (1,000 meters) in pursuit of giant squid and can stay submerged for up to 90 minutes. These intelligent mammals possess complex social structures and communication systems, using distinctive click patterns known as codas to identify themselves and communicate with pod members. Despite their formidable size, sperm whales were heavily targeted by commercial whalers, and while hunting is now largely banned, they continue to face threats from ocean pollution, fishing gear entanglement, and ship strikes.

Whale Shark The Gentle Giant

Despite having “whale” in its name, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) is actually the world’s largest fish, not a marine mammal. These gentle giants can reach lengths of up to 40-45 feet (12-14 meters) and weigh as much as 47,000 pounds (21.5 tons), making them longer than many fishing boats and dive vessels that seek them out. With their distinctive pattern of white spots and stripes on a dark blue background—unique to each individual like a fingerprint—whale sharks are easily recognizable. Unlike predatory sharks, these massive filter feeders consume primarily plankton, small fish, and fish eggs, using their 300-350 rows of tiny teeth not for biting but as a filtering apparatus. They swim with their enormous mouths open, sometimes up to 5 feet (1.5 meters) wide, filtering approximately 1,500 gallons (5,700 liters) of water per hour. Whale sharks are highly migratory, traveling thousands of miles across ocean basins following plankton blooms. Despite their impressive size and longevity—they can live 70-100 years—whale sharks face significant conservation challenges and are classified as endangered by the IUCN, primarily due to fishing pressure, vessel strikes, and habitat degradation.

Giant Manta Ray The Ocean’s Winged Wonder

With a wingspan that can exceed 23 feet (7 meters) and a weight of up to 3,000 pounds (1,350 kg), the giant manta ray (Mobula birostris) is larger than many small watercraft. These magnificent filter feeders are the largest rays in the world and glide through the water with an almost ethereal grace that belies their massive size. Unlike stingrays, mantas lack a venomous barb, making them harmless to humans despite their intimidating proportions. Their distinctive cephalic fins—horn-like structures projecting from the front of their head—help funnel plankton-rich water into their mouths during feeding. Giant mantas possess the largest brain-to-body ratio of any fish, demonstrating remarkable intelligence and even self-awareness, as they’ve been observed recognizing themselves in mirrors during scientific tests. These oceanic nomads can leap completely out of the water, reaching heights of up to 9 feet (2.7 meters), creating a spectacle that dwarfs nearby boats. Scientists believe these acrobatic jumps may serve multiple purposes, from removing parasites to communication or courtship displays. Despite their size and mobility, giant manta populations have declined dramatically, leading to their classification as endangered, primarily due to targeted fishing for their gill rakers, which are valued in some traditional medicine markets.

Basking Shark The Swimming Mouth

The basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) is the second-largest living fish, with individuals regularly reaching lengths of 26-33 feet (8-10 meters) and some exceptional specimens growing to nearly 40 feet (12 meters). These dimensions make them longer than many fishing boats and recreational vessels. Most distinctive about these enormous sharks is their massive mouth, which can open more than 3 feet (1 meter) wide while filter feeding. Despite their intimidating size and appearance, basking sharks are completely harmless to humans, feeding exclusively on zooplankton. Swimming slowly near the surface with their mouths agape, they filter approximately 1,500 gallons (5,700 liters) of water per hour through their specialized gill rakers. Unlike most sharks, basking sharks form seasonal feeding aggregations, sometimes gathering in groups of 100 or more individuals in plankton-rich areas. During winter months, these giants appear to undergo long-distance migrations and may descend to depths of 3,000 feet (900 meters). Despite their impressive dimensions, basking shark populations have been severely depleted by overfishing, particularly for their liver oil and fins, leading to their classification as endangered. Their slow reproductive rate—females don’t reach sexual maturity until about 18 years of age—makes population recovery particularly challenging.

Giant Squid The Kraken of Legend

The giant squid (Architeuthis dux) has captured human imagination for centuries, inspiring tales of sea monsters and the legendary Kraken. These deep-sea cephalopods can reach astonishing lengths of 33-43 feet (10-13 meters), with some unverified reports suggesting even larger specimens. Their size exceeds many small fishing vessels and dive boats. Unlike their more robust cousin, the colossal squid, giant squids have a more elongated body with eight arms and two longer feeding tentacles equipped with powerful suction cups lined with serrated rings for grasping prey. The first photographs of a live giant squid in its natural habitat weren’t captured until 2004, and the first video footage came only in 2012, demonstrating how elusive these creatures remain despite their enormous size. Their eyes are among the largest in the animal kingdom, measuring up to 10 inches (25 cm) in diameter—about the size of a dinner plate—an adaptation for detecting faint light in the deep ocean. Evidence of their epic battles with sperm whales, their primary predator, often comes in the form of circular scars left by the squid’s suckers on the whales’ skin. These massive invertebrates remain one of the least understood large animals on the planet, with most of our knowledge coming from specimens washed ashore or caught accidentally in fishing nets.

Leatherback Sea Turtle Prehistoric Ocean Navigator

The leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea) stands as the largest turtle species on Earth and one of the longest-surviving reptile lineages, having existed in similar form for over 100 million years. Unlike other sea turtles, leatherbacks lack a hard shell, instead possessing a leathery carapace with seven longitudinal ridges. These enormous reptiles regularly reach lengths of 6-7 feet (1.8-2.1 meters) and weights of 1,100-1,500 pounds (500-700 kg), with the largest verified specimen weighing over 2,000 pounds (900 kg)—dimensions that exceed many small watercraft such as kayaks, canoes, and dinghies. Leatherbacks are supremely adapted for oceanic life, capable of diving deeper than any other turtle species, reaching depths of 4,200 feet (1,280 meters) and staying submerged for up to 85 minutes. Their specialized physiology allows them to maintain a body temperature up to 18°F (10°C) above the surrounding water, enabling them to venture into colder waters than any other reptile. These remarkable creatures undertake some of the longest migrations of any marine animal, with some individuals traveling over 10,000 miles (16,000 km) annually between feeding and nesting grounds. Despite their impressive size and adaptability, leatherback populations have declined dramatically, with the species now classified as vulnerable globally and critically endangered in many regions, primarily due to egg harvesting, fisheries bycatch, marine pollution (particularly plastic bags which they mistake for jellyfish), and habitat loss.

Oarfish The Sea Serpent of Reality

The giant oarfish (Regalecus glesne) is believed to be the creature behind many historical sea serpent sightings, and with good reason. As the world’s longest bony fish, the oarfish can grow to an astonishing length of up to 36 feet (11 meters) and possibly more, exceeding the dimensions of many small to medium-sized boats. Despite their impressive size, these deep-sea dwellers remain mysterious, as they typically reside at depths of 660-3,300 feet (200-1,000 meters) and are rarely seen alive by humans. The oarfish’s ribbon-like, silvery body features a vibrant red dorsal fin that runs the entire length of its back, culminating in a distinctive crest of 10-50 long rays that stand upright on its head, resembling a crown. These peculiar fish lack scales, instead having a coating of guanine that gives them their silvery appearance. Their unusual method of locomotion—undulating their dorsal fin while keeping their body rigid—contributes to their serpentine appearance when observed. Oarfish feed primarily on krill, small crustaceans, and other zooplankton, using their small, toothless mouths. Most of our knowledge about these elusive creatures comes from specimens that have washed ashore, often when weakened or dying, as healthy oarfish rarely approach the surface. Japanese folklore suggests that oarfish beachings may precede earthquakes, though scientific evidence for this connection remains inconclusive.

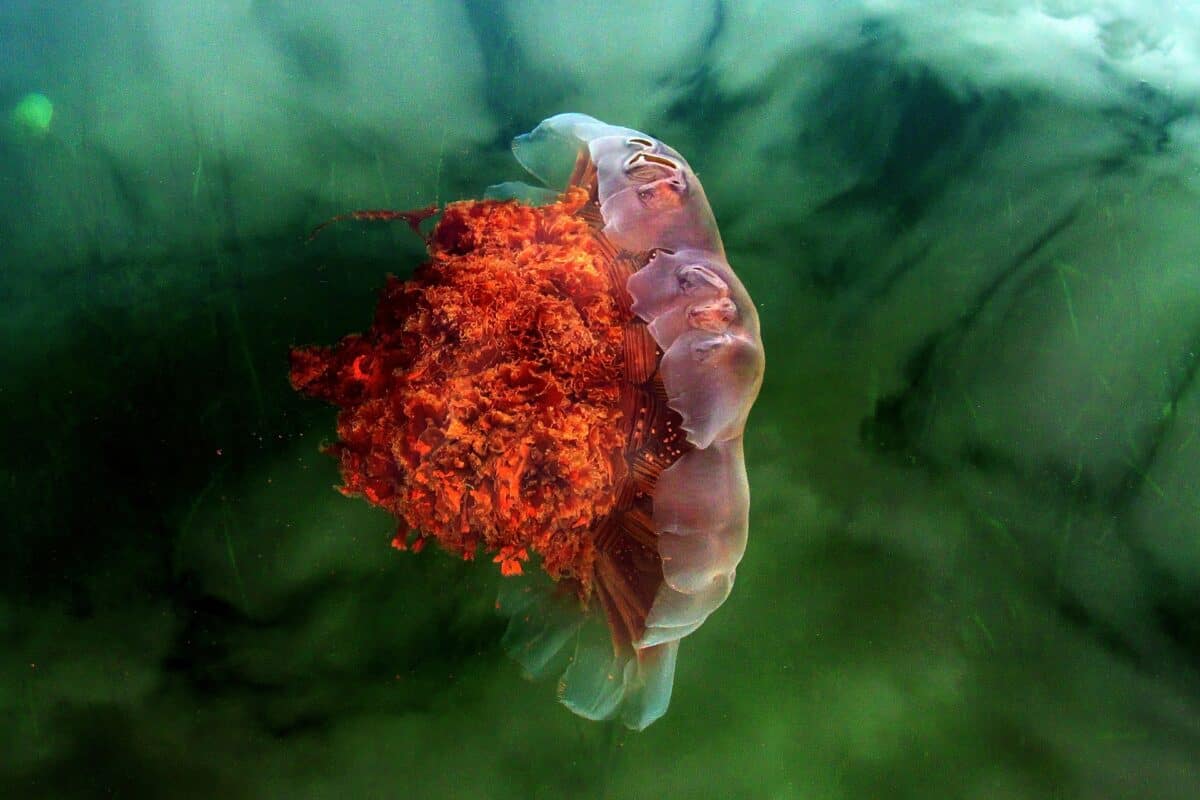

Lion’s Mane Jellyfish The Ocean’s Floating Colossus

The lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea capillata) earns its place among the ocean’s most impressive creatures as the largest known species of jellyfish in the world. These gelatinous giants can develop bell diameters exceeding 7 feet (2.1 meters), with their tentacles trailing an astonishing 120 feet (36.5 meters) behind them—longer than a standard blue whale and exceeding the length of many recreational boats and small yachts. The largest documented specimen, found washed ashore in Massachusetts Bay in 1870, had a bell diameter of 7.5 feet (2.3 meters) and tentacles stretching 120 feet, with some scientists suggesting that specimens with even longer tentacles may exist in the colder regions of their habitat. These arctic and subarctic dwellers feature a distinctive reddish-orange bell with eight clusters of tentacles, which can contain up to 1,200 individual stinging appendages. Each tentacle is lined with thousands of specialized cells called nematocysts that deliver toxins to immobilize prey such as fish, smaller jellyfish, and zooplankton. While their sting is painful to humans, it is rarely fatal, though it can cause severe dermatitis, muscle cramps, and respiratory issues. These remarkable creatures have a complex life cycle that includes both fixed polyp and free-swimming medusa stages, with the largest specimens typically found in the coldest waters of the Arctic, North Atlantic, and North Pacific Oceans.

Sunfish The Floating Ocean Oddity

The ocean sunfish (Mola mola) stands as one of the most bizarre-looking creatures in the sea and holds the title of the heaviest known bony fish in the world. These peculiar fish can reach weights of up to 2.5 tons (2,268 kg) and lengths of 10-11 feet (3-3.3 meters), with their unique, almost truncated appearance making them wider than many small boats when measured from the tip of their dorsal fin to their anal fin—up to 14 feet (4.2 meters). Their unusual body shape resembles a swimming head with a rudder, having evolved to lose their caudal fin during development, instead developing enlarged dorsal and anal fins that they use for propulsion in a sculling motion. Despite their massive size, sunfish feed primarily on nutritionally poor jellyfish, requiring them to consume vast quantities to maintain their bulk. These remarkable fish are prolific breeders, with females capable of producing up to 300 million eggs at once—more than any other known vertebrate. Sunfish are often seen basking at the ocean’s surface, lying on their sides, a behavior scientists believe helps them thermoregulate after deep dives and may allow seabirds to pick parasites from their skin. Despite their size making them difficult for predators.

Conclusion:

The ocean remains one of the most mysterious and awe-inspiring frontiers on Earth, home to creatures of staggering proportions that challenge our understanding of biology and scale. From the immense blue whale to the ethereal lion’s mane jellyfish and the elusive giant squid, these marine giants exemplify the diversity, adaptability, and grandeur of life in the deep. Their sizes often surpass those of boats and even rival small ships, serving as humbling reminders of nature’s majesty and the evolutionary ingenuity required to thrive in such a vast and variable environment. Yet, alongside admiration must come responsibility. Many of these species face growing threats from human activity—climate change, pollution, habitat destruction, and commercial exploitation. Protecting these extraordinary animals is not only a matter of conservation but also of preserving the integrity and wonder of the ocean itself. In understanding and safeguarding them, we ensure that the stories of these giants of the sea continue to inspire generations to come.

- 11 Mammals That Live in Water - August 20, 2025

- 10 Birds That Use Mimicry to Survive - August 20, 2025

- 12 Times Nature Created Something Completely Unexplainable - August 20, 2025