The ocean, covering more than 70% of our planet, remains one of Earth’s greatest mysteries. Despite centuries of exploration, we’ve mapped less than 20% of the seafloor, leaving vast regions unexplored and countless creatures undiscovered. The depths of our oceans hold secrets that continue to surprise even the most seasoned marine biologists, with new species being identified regularly. Among these discoveries are massive creatures that seem almost mythological in their proportions and appearances. From the confirmed giants that rarely surface to theoretical behemoths that might still exist in the deepest trenches, the ocean’s capacity to harbor enormous life forms is both fascinating and humbling. This article explores twelve ocean giants that could be lurking beneath the waves—some we know exist but rarely see, others that might still be waiting for their scientific debut.

The Colossal Squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni)

The Colossal Squid represents one of the ocean’s most elusive giants. With eyes the size of dinner plates (up to 11 inches in diameter)—the largest of any known animal—these deep-sea dwellers can reach lengths of up to 46 feet and weights exceeding 1,100 pounds. Unlike their more famous cousin, the Giant Squid, Colossal Squids have shorter but more massive bodies with hooks on their tentacles instead of just suckers, making them formidable predators. They inhabit the deep Antarctic waters, rarely venturing above 3,300 feet.

Scientists have documented very few specimens, with most of our knowledge coming from partially digested remains found in sperm whale stomachs or rare, damaged specimens caught by deep-sea fishing vessels. The first complete adult specimen was captured in 2007 near Antarctica, providing unprecedented insight into these mysterious creatures. The scarcity of sightings suggests that healthy, mature Colossal Squids might be even larger than we currently estimate, continuing to elude human observation in the lightless depths they call home.

The Megamouth Shark (Megachasma pelagios)

The Megamouth Shark remains one of the most mysterious large sharks in our oceans, with fewer than 100 confirmed sightings since its discovery in 1976. Growing up to 18 feet long, this filter-feeding giant has a distinctively large, circular mouth lined with tiny teeth. Its discovery shocked marine biologists, as it represented not just a new species but an entirely new genus and family of shark that had somehow escaped scientific documentation despite its massive size.

Unlike other filter-feeding sharks that actively swim through the water to collect plankton, the Megamouth uses bioluminescent tissues inside its mouth to attract plankton and small fish while swimming slowly with its enormous jaws open. It typically inhabits depths between 400-2,500 feet, following a daily vertical migration pattern—swimming up toward the surface at night to feed and descending to deeper, darker waters during daylight. The rarity of sightings suggests these enormous sharks may be more abundant than we realize, quietly patrolling the mesopelagic zone far from human observation.

The Greenland Shark (Somniosus microcephalus)

The Greenland Shark may be the longest-lived vertebrate on Earth, with some individuals estimated to be 300-500 years old. These ancient mariners typically grow to 21 feet long and weigh up to 2,200 pounds, moving through the cold, dark waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans at a glacial pace of less than 1 mile per hour. Their extremely slow metabolism and growth rate (growing less than 1 centimeter per year) contribute to their extraordinary longevity.

Despite their size, Greenland Sharks remained largely unknown to science until relatively recently. Their flesh contains high levels of trimethylamine oxide, which converts to trimethylamine (a powerful toxin) when digested unless properly processed. Interestingly, almost all Greenland Sharks carry parasitic copepods that attach to their corneas, rendering them partially blind—yet they successfully hunt seals, fish, and even reindeer that have fallen into the water. Scientists believe many more of these ancient giants may patrol the depths than previously thought, with their slow movement and deep-water habitat keeping them hidden from human observation for centuries.

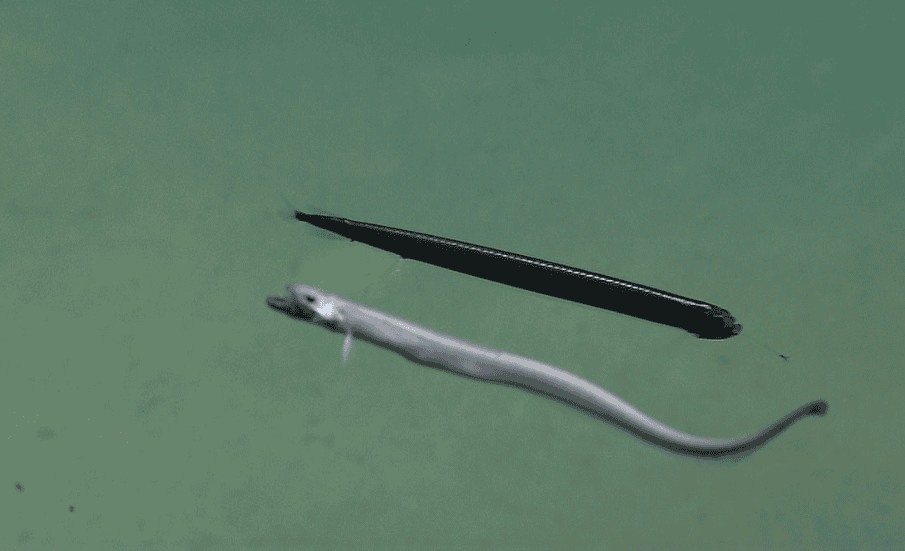

The Giant Oarfish (Regalecus glesne)

The Giant Oarfish, with its serpentine body stretching up to 36 feet long, is believed to be the source of many “sea serpent” sightings throughout history. These ribbon-like creatures normally inhabit depths between 660 and 3,300 feet, making live sightings extremely rare. Most human encounters occur when dying or dead specimens wash ashore, feeding the mythology surrounding these remarkable animals. Their silvery, compressed bodies feature a dorsal fin running almost their entire length, crowned with an elaborate, bright red crest of spines on their heads.

Japanese folklore considers oarfish sightings to be omens of earthquakes, as some believe the normally deep-dwelling fish rise to shallower waters when they sense seismic activity. While scientific evidence for this connection remains inconclusive, these beautiful giants maintain an air of mystery. Their gelatinous bodies, lacking significant swimming muscles, suggest they move primarily by undulating their dorsal fin while remaining vertically oriented in the water column. Despite being the longest bony fish in the sea, we know surprisingly little about their behavior, reproduction, or population size, making them perfect candidates for continued deep-sea discoveries.

The Black Dragonfish (Idiacanthus atlanticus)

Though smaller than other creatures on this list at approximately 16 inches long, the female Black Dragonfish earns its place through its terrifying appearance and specialized adaptations for deep-sea hunting. These fish possess bioluminescent photophores along their bodies and a barbel (a specialized chin appendage) that acts as a light lure for prey. Their most notable feature is their disproportionately large mouth filled with fang-like teeth so long they don’t fit inside the mouth when closed, instead protruding outward like a nightmarish bear trap.

What makes the Black Dragonfish particularly fascinating is its ability to produce red light—a rarity in the deep sea where most creatures can only see blue wavelengths. This gives the dragonfish a significant hunting advantage, as it can essentially use “invisible” red light to spot prey without being detected. The extreme sexual dimorphism of the species adds another layer of mystery; males are tiny (about 2 inches), brown, lack teeth, and possess non-functional digestive systems, living only long enough to reproduce. Scientists believe many more specimens and potentially related species exist in the unexplored deep ocean, where their specialized adaptations allow them to thrive in one of Earth’s most extreme environments.

The Japanese Spider Crab (Macrocheira kaempferi)

The Japanese Spider Crab holds the record for the largest arthropod in the world when measured by leg span, which can reach an astonishing 12 feet from claw to claw. These enormous crustaceans inhabit the waters around Japan, primarily at depths of 150 to 2,000 feet. Despite their intimidating size, they are primarily scavengers rather than predators, using their long, spindly legs to traverse the ocean floor in search of decaying organic matter and small marine animals.

With lifespans potentially exceeding 100 years, these crabs represent one of the ocean’s most enduring species. Their orange-red carapaces are often covered with symbiotic organisms like sponges and anemones, providing natural camouflage against predators. Young spider crabs actively decorate themselves with marine debris and organisms for additional protection. While commercial fishing has impacted their populations near Japan, scientists believe substantial numbers may exist in deeper, unexplored areas throughout their range. Their preference for deep, cold waters means many aspects of their natural behavior remain undocumented, with the largest specimens potentially remaining undiscovered in inaccessible underwater canyons.

The Giant Isopod (Bathynomus giganteus)

Resembling a roly-poly bug of nightmarish proportions, the Giant Isopod grows up to 16 inches long and represents one of the largest examples of abyssal gigantism—the tendency for deep-sea creatures to grow much larger than their shallow-water relatives. These crustaceans inhabit the cold, dark ocean floor at depths between 550 and 7,020 feet, where their size helps them withstand the enormous pressure and scarcity of food. With their segmented exoskeletons and multiple pairs of legs, they look remarkably like their tiny terrestrial cousins but have evolved to thrive in one of Earth’s most extreme environments.

Giant Isopods have adapted to the food scarcity in the deep sea by developing the ability to go without eating for extraordinary periods—one specimen in captivity survived for five years without consuming any food. When they do feed, they often gorge themselves until their digestive tract is completely full. They primarily scavenge on dead marine animals that sink to the ocean floor, but can also be active predators when the opportunity arises. While we know of their existence, their deep-sea habitat means many aspects of their lifecycle, behavior, and potential size variations remain mysterious, with larger specimens potentially lurking in unexplored deep-sea trenches.

The Lion’s Mane Jellyfish (Cyanea capillata)

The Lion’s Mane Jellyfish holds the title of the world’s largest known jellyfish, with bell diameters reaching 7 feet and tentacles extending an astonishing 120 feet—longer than a blue whale. These gelatinous giants primarily inhabit the cold waters of the Arctic, northern Atlantic, and northern Pacific Oceans, where their reddish-orange bells and cascading tentacles create a spectacular, if dangerous, sight. Their size varies with latitude, with the largest specimens found in Arctic waters.

Despite their enormous size, Lion’s Mane Jellyfish remain mostly mysterious to scientists. Their lifecycle includes multiple stages, from microscopic larvae to the massive adult medusae we recognize. Each jellyfish can have up to 1,200 tentacles arranged in eight distinct clusters, each loaded with powerful stinging cells called nematocysts. While their sting is painful to humans, it’s rarely lethal. These jellyfish serve as floating ecosystems, providing shelter for certain fish species and food for others. Climate change and warming oceans may be affecting their distribution and maximum size, with some scientists hypothesizing that even larger specimens might exist in remote polar regions that remain understudied due to their inhospitable conditions.

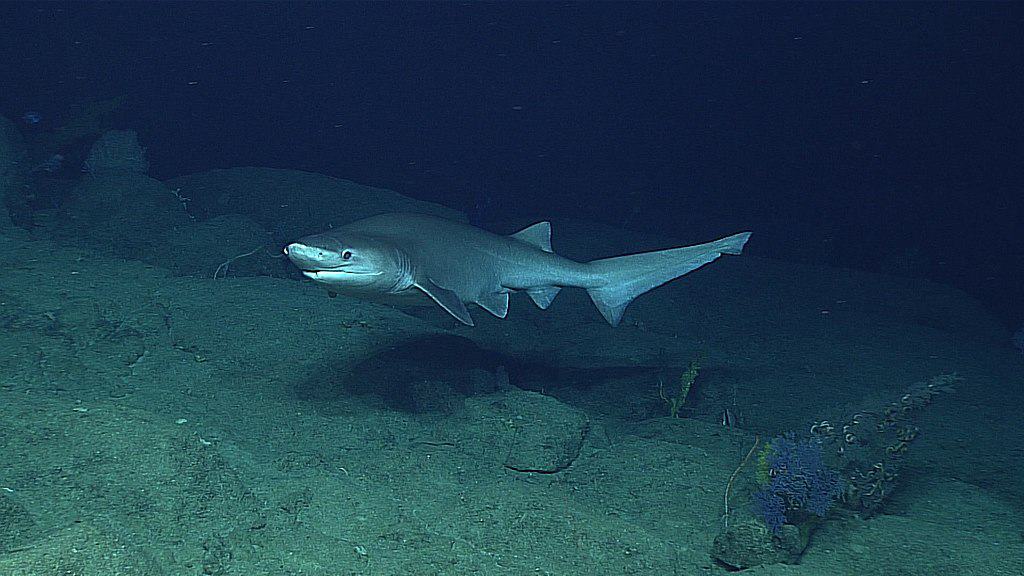

The Bluntnose Sixgill Shark (Hexanchus griseus)

The Bluntnose Sixgill Shark represents a living fossil, with a lineage dating back over 200 million years and a body plan that has changed little from its Jurassic ancestors. Unlike most modern sharks that have five gill slits, the Sixgill—as its name suggests—possesses six. Growing up to 26 feet long and weighing over 1,300 pounds, these primitive giants typically inhabit depths between 300 and 6,000 feet, making them one of the deepest-dwelling large shark species.

Their preference for deep, cold waters and slow swimming speed has kept them largely hidden from human observation throughout history. They possess a single, small dorsal fin set far back on their body (unlike the prominent dorsal fins of many familiar sharks), fluorescent green eyes adapted for low-light conditions, and a broad, blunt snout. Sixgills are opportunistic predators and scavengers, consuming everything from fish and marine mammals to other sharks and whale carcasses. Scientists believe significant populations may exist throughout the world’s oceans, particularly in deep submarine canyons and continental shelves, with potentially larger specimens than currently documented lurking in the least explored ocean regions.

The Giant Squid (Architeuthis dux)

The Giant Squid has captured human imagination for centuries, appearing in maritime legends as the fearsome kraken. Modern science has confirmed these creatures reach incredible sizes, with females growing up to 43 feet long, including their tentacles. Despite their massive proportions, living Giant Squids weren’t photographed in their natural habitat until 2004, and the first live video footage wasn’t captured until 2012—testaments to how effectively these enormous invertebrates evade human observation.

Unlike their more robust relative, the Colossal Squid, Giant Squids have a more elongated body and tentacles lined with hundreds of suction cups, each ringed with sharp, serrated chitin to secure struggling prey. They possess the largest eyes in the animal kingdom, measuring up to 10 inches in diameter—an adaptation for detecting the faint bioluminescence of prey and the silhouettes of approaching predators in their dim, deep-water environment. While we’ve documented their existence, many scientists believe we’ve yet to encounter the true maximum size these animals can reach. Most specimens studied are juveniles or damaged adults recovered after death, suggesting that pristine, mature specimens inhabiting the least accessible parts of our oceans might exceed the currently accepted size records.

The Big Red Jellyfish (Tiburonia granrojo)

Discovered only in 2003, the Big Red Jellyfish (also called the Giant Phantom Jelly) represents how much remains unknown in our oceans. This crimson-colored behemoth can grow to over 4.9 feet in bell diameter with arms extending up to 20 feet. Unlike typical jellyfish that have numerous tentacles, the Big Red possesses four to seven thick, fleshy arms used for capturing prey. It inhabits the mesopelagic zone (approximately 2,000-4,900 feet deep) of the Pacific Ocean, where sunlight barely penetrates.

What makes this jellyfish particularly intriguing is how it remained undiscovered until the 21st century despite its enormous size and distinctive appearance. Scientists have only encountered it about 25 times since its discovery, highlighting how effectively deep-sea creatures can evade human detection. The jellyfish’s bright red coloration actually serves as camouflage in its deep habitat, as red light doesn’t penetrate to these depths, rendering the animal effectively invisible to both predators and prey. Given how recently this massive species was discovered and how infrequently it’s observed, marine biologists speculate that many more similarly large, undiscovered jellyfish species likely inhabit the ocean’s twilight zone and beyond.

The Conclusion: Oceans of Mystery

The twelve ocean giants explored in this article represent only a fraction of the mysterious megafauna that may exist in our planet’s vast, unexplored marine environments. With less than 20% of the ocean floor mapped in detail and even less of the water column thoroughly studied, the potential for undiscovered enormous creatures remains significant. Historical patterns suggest we should expect continued discoveries; many of the creatures discussed here were either unknown or considered mythological until relatively recently, and new large species continue to be documented even in the 21st century.

As technology advances, allowing scientists to explore deeper, colder, and more remote ocean regions, we will undoubtedly encounter more enormous animals that have thus far escaped human detection. The recent discoveries of creatures like the Big Red Jellyfish and continued rare sightings of Megamouth Sharks remind us that our understanding of marine life remains incomplete. Climate change and human activities increasingly threaten these animals before we even have the chance to document their existence, adding urgency to deep-sea exploration efforts.

Perhaps most humbling is the recognition that despite our technological advancements, the ocean’s vastness ensures it will likely always retain some of its mysteries. The next great oceanic giant might be glimpsed during a deep-sea research expedition tomorrow, or it might continue dwelling in the darkness for centuries to come, a reminder of how much we have yet to learn about our blue planet. As we continue exploring the last great frontier on Earth, we should approach the ocean with both scientific curiosity and profound respect for the undiscovered life it shelters beneath its surface.

- 14 Weirdest Looking Animals on Earth - August 15, 2025

- 13 Creatures That Don Not Need Eyes to See - August 15, 2025

- 13 Wild Species That Can Clone Themselves - August 15, 2025