When we think of animals that soar through the air, birds and bats typically come to mind. However, nature has evolved remarkable adaptations that allow many creatures to glide through the air without true wings. These extraordinary animals have developed specialized membranes, flaps of skin, or unique body structures that create lift and allow them to traverse distances between trees, escape predators, or hunt effectively. From tropical rainforests to deserts, these gliding specialists have perfected the art of aerial movement despite lacking the powered flight capabilities of their winged counterparts. Let’s explore 14 fascinating animals that have mastered the skies through ingenious evolutionary adaptations, demonstrating nature’s incredible diversity of solutions to the challenge of aerial locomotion.

Flying Squirrels Masters of Forest Canopy Travel

Flying squirrels represent one of the most well-known groups of gliding mammals, with over 50 species spread across the Northern Hemisphere and Southeast Asia. Despite their name, these rodents don’t actually fly—they glide using a patagium, a furry membrane that stretches from their wrists to their ankles. When a flying squirrel leaps from a tree, it spreads its limbs to extend this membrane, creating a wing-like surface that can catch air. The small cartilaginous projection from their wrist (the styliform cartilage) helps them control their glide, while their flat, rudder-like tail provides stability. Some species, like the northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus), can glide impressive distances of up to 90 meters while maintaining remarkable precision, allowing them to navigate complex forest canopies without descending to the predator-rich forest floor.

Colugos The Living Gliding Blankets

Colugos, sometimes called flying lemurs despite not being lemurs nor capable of true flight, possess the most extensive gliding membranes of any mammal. These Southeast Asian mammals have a patagium that stretches from their neck to their fingertips, continuing to their tail and even between their toes, essentially turning their entire body into a living glider. There are only two species of colugos: the Sunda flying lemur (Galeopterus variegatus) and the Philippine flying lemur (Cynocephalus volans). These nocturnal creatures can glide up to 70 meters with minimal loss of height, making them incredibly efficient at traversing forest gaps. Their specialized membrane is so effective that when stretched out, it resembles a rectangular blanket with a tail, allowing these animals to achieve glide ratios (horizontal distance traveled divided by vertical drop) of up to 15:1—among the best in the animal kingdom.

Sugar Gliders Pocket-Sized Aerial Navigators

Sugar gliders (Petaurus breviceps) are small marsupials native to Australia, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea that have become popular exotic pets due to their endearing appearance and gliding abilities. Weighing just 100-160 grams, these diminutive creatures possess a membrane called the patagium that extends from their fifth finger to their first toe. When they leap from trees, they extend their limbs to stretch this membrane and create a square-shaped gliding surface. Their name derives from their fondness for nectar and sap, though they are omnivorous and also consume insects and small vertebrates. Sugar gliders can glide up to 50 meters in a single bound, using their long, fluffy tails as rudders to control direction. Remarkably, they can make mid-air turns of up to 180 degrees, demonstrating exceptional aerial maneuverability despite their small size.

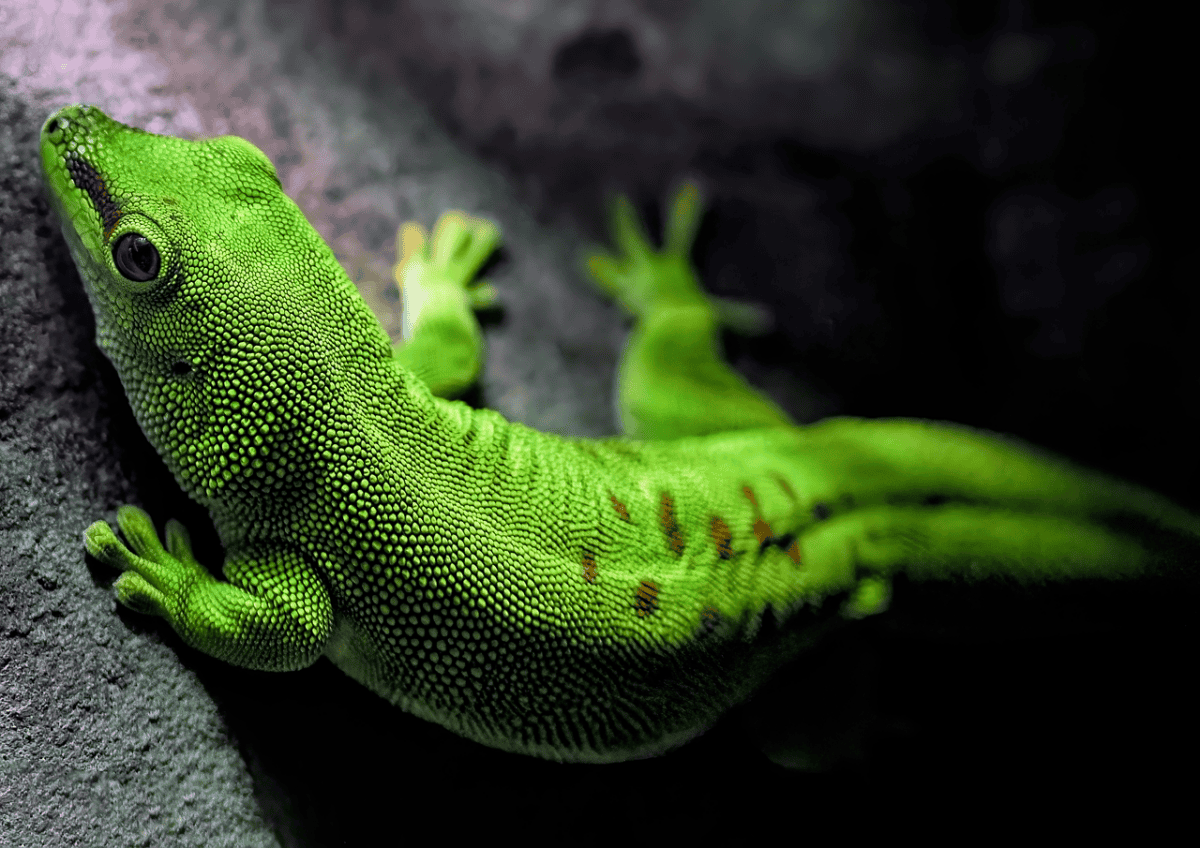

Flying Geckos Reptilian Gliding Specialists

Several gecko species have evolved gliding capabilities, with the most prominent being the parachute gecko or flying gecko (Ptychozoon genus). These remarkable reptiles, found primarily in Southeast Asia, have developed flaps of skin along their limbs, tail, and body that act as airfoils when extended. When threatened, these geckos can launch themselves from trees and spread their skin flaps to slow their descent and control their landing. The skin flaps are fringed and scalloped, increasing surface area and improving aerodynamic performance. Additionally, their flattened tails serve as effective rudders during glides. The webbing between their toes not only aids in climbing but also contributes to their gliding surface area. Some flying gecko species can glide distances of over 60 feet (18 meters), allowing them to escape predators and move efficiently through their forest habitat without descending to the ground.

Wallace’s Flying Frog Amphibian Parachutist

Wallace’s flying frog (Rhacophorus nigropalmatus), named after the naturalist Alfred Russel Wallace, represents one of the most specialized gliding amphibians. Native to the rainforests of Malaysia, Indonesia, and parts of Thailand, this bright green frog has enormous webbed feet that serve as effective parachutes when it leaps from the canopy. The webbing between its toes can expand to create a surface area nearly four times the size of the frog’s body. When gliding, Wallace’s flying frog stretches its limbs to maximize the use of its webbed feet and flattens its body to increase air resistance. It can glide up to 50 feet (15 meters) and make controlled descents with remarkable accuracy. Additionally, specialized toe pads help it stick to surfaces upon landing. This adaptation allows the frog to travel between breeding sites during the rainy season and escape predators without having to descend to the forest floor.

Flying Snakes Serpentine Sky Surfers

Perhaps the most unexpected gliders in the animal kingdom are the flying snakes of the genus Chrysopelea, found in South and Southeast Asia. Lacking any obvious external adaptations for gliding, these snakes employ a fascinating technique to achieve aerial locomotion. When preparing to glide, a flying snake climbs to a high point, extends its body away from the branch, and launches itself with a powerful jump. Mid-air, it flattens its body by spreading its ribs and pulling in its ventral surface, transforming its cylindrical body into a concave wing. The most impressive species, the paradise tree snake (Chrysopelea paradisi), can glide over 100 feet (30 meters) horizontally. During flight, these snakes perform undulating S-shaped movements, creating vortices that generate lift and allowing for controlled flight paths. Remarkably, flying snakes can make mid-air turns and even glide around obstacles—aerodynamic feats that continue to intrigue biophysicists studying their unique locomotion.

Flying Dragons Real-life Mini Dragons

Flying dragons (Draco species) represent nature’s closest approximation to the mythical dragons of legend, albeit in miniature form. These small lizards, native to Southeast Asia, possess elongated ribs that can be extended outward to support a wing-like membrane called a patagium. When not gliding, these “wings” fold neatly against the body. When the lizard needs to glide, it extends its ribs, stretching the patagium into a wing-like structure that can span up to twice the animal’s body width. With their specialized anatomy, flying dragons can glide distances of up to 60 meters (200 feet) with remarkable control, losing only about 10 meters in height over that distance—an impressive glide ratio that allows them to soar between trees without descending to the predator-rich forest floor. Males often utilize their gliding abilities in territorial displays and to move quickly between trees during mating season, adding a social dimension to this evolutionary adaptation.

Flying Fish Marine Gliding Specialists

Flying fish (family Exocoetidae) have evolved an extraordinary ability to escape aquatic predators by taking to the air. These marine fish possess greatly enlarged pectoral fins that serve as wings when extended. Some species also have enlarged pelvic fins, effectively giving them four “wings.” To initiate a glide, a flying fish builds up speed underwater, reaching approximately 37 mph (60 km/h), then breaks the surface while rapidly beating its tail. Once airborne, it extends its specialized fins and can glide for distances of up to 650 feet (200 meters) in a single flight. The most accomplished species can reach heights of 20 feet (6 meters) above the water’s surface. Remarkably, some flying fish can execute multiple consecutive glides by dipping their tail back into the water to gain momentum without fully submerging—a technique called “taxiing” that can extend their total aerial journey to over a quarter-mile (400 meters). Their aerial capabilities not only help them escape predators like tuna and mackerel but also reduce the energy costs of traveling through water, which offers much higher resistance than air.

Gliding Ants Arboreal Aeronauts

Several ant species that dwell in the canopies of tropical rainforests have developed remarkable gliding abilities. The most studied of these is Cephalotes atratus, commonly known as the gliding ant or turtle ant, native to the forests of South America. When these ants fall or are knocked from their tree branches—a common occurrence in their high-canopy home—they don’t simply plummet to the forest floor. Instead, they can control their descent by extending their legs and flattening their bodies, effectively gliding backward toward the tree trunk. Their specialized legs and flattened heads create enough aerodynamic lift to direct their fall, allowing them to land on the same tree they fell from rather than the forest floor where they would face numerous predators and the challenging task of relocating their colony. Research has shown that these ants can achieve glide angles of about 75 degrees and complete 180-degree turns mid-air to orient themselves toward the tree trunk. This remarkable adaptation dramatically increases their survival chances in the arboreal environment and represents one of the few examples of controlled aerial descent in insects.

Flying Frogs of Southeast Asia Amphibian Aviators

Beyond Wallace’s flying frog, several other frog species in Southeast Asia have independently evolved gliding adaptations. Species like the Malabar gliding frog (Rhacophorus malabaricus) and the Golden flying frog (Rhacophorus kio) possess extensive webbing between their digits that serves as effective parachutes during aerial descents. These frogs typically inhabit the upper canopies of tropical rainforests and use their gliding abilities to move between trees during mating season and to escape predators. When launching into a glide, these frogs extend all four limbs to maximize their webbed surface area and can rotate their feet to optimize air resistance. Their lightweight bodies and specialized toe pads lined with microscopic suction cups ensure they can both glide efficiently and secure a firm grip upon landing. Some species can change direction mid-flight by adjusting the position of their limbs, demonstrating remarkable control despite lacking true wings. These adaptations allow flying frogs to navigate the three-dimensional environment of the rainforest canopy with greater efficiency than their ground-dwelling relatives.

Feather-tailed Possums Australia’s Tiny Gliders

The feather-tailed possum or pygmy gliding possum (Acrobates pygmaeus) of Australia represents one of the smallest gliding mammals in the world, weighing just 10-15 grams—about the same as a few sheets of paper. Despite its diminutive size, this marsupial possesses a remarkable gliding membrane (patagium) that extends from the elbow to the knee. What makes this tiny glider unique is its feather-like tail, which resembles a bird’s feather in both appearance and function. The flattened tail has stiff hairs arranged in rows on either side, creating an increased surface area that provides additional lift and stability during glides. These nocturnal creatures can glide up to 25 meters while maintaining precise control over their trajectory. Their tiny size allows them to feed on nectar and pollen that larger gliders cannot access, giving them a specialized ecological niche in Australia’s forest ecosystems. The feather-tailed possum demonstrates that effective gliding adaptations can evolve even in extremely small-bodied animals, further showcasing the versatility of gliding as a locomotory strategy.

Gliding Mammals of Africa Anomalures

Africa has its own unique gliding mammals in the form of scaly-tailed squirrels or anomalures (family Anomaluridae). Despite their squirrel-like appearance, these animals are not closely related to true squirrels but represent a distinct family that evolved gliding adaptations independently. Anomalures possess a gliding membrane similar to flying squirrels, extending from their front to hind limbs, but with several unique features. Most notably, they have a series of pointed scales on the underside of their tail that serve as climbing spikes, allowing them to cling to vertical tree trunks—an adaptation not seen in other gliding mammals. The Lord Derby’s anomalure (Anomalurus derbianus) can reach sizes of up to 1 meter in length including its tail and can glide distances of over 100 meters. These nocturnal creatures inhabit the rainforests of central and western Africa, where their gliding abilities allow them to efficiently move between fruiting trees while minimizing energy expenditure and predation risk. Their specialized diet includes bark, seeds, fruits, and leaves, with some species having specialized teeth for stripping bark to access the nutritious cambium layer beneath.

Paradise Tree Snake The Serpentine Sky Master

The paradise tree snake (Chrysopelea paradisi) deserves special recognition beyond the general flying snake category due to its exceptional aerial abilities. This slender, brightly colored snake native to Southeast Asia has perfected the art of aerial locomotion despite lacking any obvious external adaptations for gliding. When initiating a glide, the paradise tree snake leaps from a high perch and immediately transforms its body from cylindrical to concave by flaring its ribs and contracting its ventral surface. High-speed camera studies have revealed that these snakes perform an intricate undulating motion in mid-air, creating vortices that generate lift—a phenomenon that continues to puzzle aerodynamic engineers. The paradise tree snake can glide at angles as shallow as 13 degrees from the horizontal, allowing it to cover horizontal distances up to 100 feet (30 meters) in a single glide. More remarkably, it can make complex aerial maneuvers, including 90-degree turns to navigate around obstacles or adjust its trajectory toward specific landing targets. The snake’s flattened body essentially transforms into a dynamic wing that continuously adjusts throughout the glide, making it one of the most sophisticated wingless flyers in the animal kingdom.

Conclusion: The Remarkable World of Airborne Animals

The diverse array of gliding animals showcases nature’s remarkable ingenuity in solving the challenge of aerial locomotion without true powered flight. From mammals with specialized membranes to reptiles that reshape their bodies mid-air, these evolutionary adaptations demonstrate convergent evolution—where similar traits develop independently in unrelated species facing similar environmental pressures. The ability to glide provides numerous advantages, including efficient movement through forest canopies, escape from predators, and access to food resources unavailable to ground-dwelling animals. What’s particularly fascinating is how these animals achieve comparable functional outcomes through vastly different anatomical adaptations, from the expansive skin membranes of colugos to the flattened tails of feather-tailed possums. As we continue to study these remarkable creatures through advanced biomechanical analysis and high-speed videography, they offer inspiration for human-engineered gliding devices and provide deeper insights into the evolutionary processes that drive such specialized adaptations in nature’s endless quest for survival.

- 10 Common Chicken Behaviors and What They Mean - August 9, 2025

- 14 Creatures That Can Freeze and Thaw Back to Life - August 9, 2025

- 10 Animals That Risked Their Lives to Save Humans - August 9, 2025