In the harsh, frozen landscapes of our planet, some organisms have evolved a remarkable survival strategy that seems to defy death itself. These extraordinary creatures can enter a state of suspended animation when temperatures plummet, essentially freezing solid, only to thaw and return to life when conditions improve. This ability, often called cryobiosis, represents one of nature’s most astonishing adaptations. From microscopic tardigrades to certain frogs that can survive with two-thirds of their body water turned to ice, these animals challenge our understanding of what it means to be alive. Let’s explore 15 remarkable creatures that have mastered the art of freezing and reviving, revealing the ingenious mechanisms that allow them to cheat death by ice.

14. Wood Frogs (Lithobates sylvaticus)

Wood frogs are perhaps the most famous vertebrate freeze-tolerant animals. Native to North America, these remarkable amphibians can survive having 65-70% of their body water converted to ice during winter months. When temperatures drop, wood frogs produce large amounts of glucose and urea that act as natural antifreeze compounds, preventing their cells from being damaged by ice crystals. Their hearts stop beating, they cease breathing, and their blood stops flowing. To the touch, they feel like ice cubes with legs. Yet when spring arrives and temperatures rise, these frogs gradually thaw from the inside out, with their hearts beginning to beat even while ice still clings to their skin. Within hours of thawing, wood frogs hop away as if nothing happened, ready to breed in early spring before other amphibian competitors emerge.

13. Tardigrades (Water Bears)

Tardigrades, also known as water bears or moss piglets, are microscopic animals that have become celebrities in the scientific world for their incredible resilience. These eight-legged micro-animals, measuring just 0.5mm when fully grown, can survive temperatures from near absolute zero (-458°F/-272°C) to well above boiling. When facing extreme cold, tardigrades enter a state called cryptobiosis, replacing the water in their bodies with a sugar called trehalose that prevents destructive ice crystal formation. They curl into a dehydrated ball called a “tun,” reducing their water content to less than 3%. In this state, their metabolism slows to less than 0.01% of normal, and they can remain frozen for decades—possibly even centuries—before reviving when conditions improve. Scientists have successfully revived tardigrades after 30 years in a frozen state, making them among the most durable creatures on Earth.

12. Arctic Woollybear Caterpillars (Gynaephora groenlandica)

The Arctic woollybear caterpillar has evolved one of the most impressive freeze-tolerance strategies among insects. Native to the high Arctic regions of North America, these caterpillars experience some of the harshest winter conditions on the planet. What makes them truly remarkable is their extended life cycle—while most caterpillars mature in weeks or months, Arctic woollybears can take up to 14 years to develop into moths, surviving through multiple freeze-thaw cycles. When winter approaches, these fuzzy caterpillars produce glycerol and other antifreeze compounds that protect their tissues as they freeze solid. They can survive temperatures as low as -70°C (-94°F), with their hearts stopping completely and no detectable metabolism. Each summer, they thaw, feed for a brief period, and then freeze again when winter returns. This cycle repeats for over a decade until they finally pupate and emerge as moths—making them masters of the freeze-thaw lifestyle.

11. Spring Tails (Collembola)

Springtails are tiny hexapods that, despite their minute size (typically 0.25-10mm), have developed sophisticated mechanisms for surviving freezing temperatures. Found in soil worldwide, including Antarctica, these creatures have evolved two distinct strategies for dealing with extreme cold. Some species are freeze-avoidant, producing antifreeze proteins that prevent ice formation in their bodies even when surrounded by freezing conditions. Others are freeze-tolerant, allowing controlled ice formation in certain body compartments while protecting vital tissues. What makes springtails particularly interesting is their ability to rapidly switch between active and frozen states during unpredictable weather fluctuations. In the Antarctic species Cryptopygus antarcticus, individuals can survive multiple freeze-thaw cycles within a single day as temperatures fluctuate. They accomplish this using special proteins that not only prevent damaging ice formation but also help maintain cell membrane integrity during the physical stress of freezing and thawing. These adaptations allow springtails to be among the most abundant arthropods in polar environments.

10. Painted Turtle Hatchlings (Chrysemys picta)

Painted turtle hatchlings perform an extraordinary feat of survival during their first winter of life. Unlike adult turtles, which typically overwinter underwater, painted turtle hatchlings often remain in their underground nests after hatching in the fall, enduring freezing temperatures until spring. These baby turtles can survive having up to 50% of their body water converted to ice. Their adaptation includes producing large amounts of glucose and glycerol as cryoprotectants, which act as natural antifreeze. What’s particularly remarkable is that their brains remain partially functional even while frozen, allowing for core neurological processes to continue at extremely low levels. Studies have shown that painted turtle hatchlings can survive temperatures as low as -8°C (17.6°F) for over 72 hours, with their hearts completely stopped. When spring warming begins, these resilient hatchlings thaw from their frozen state, resume normal metabolic functions, and dig their way out of the nest to begin their aquatic lives—an incredible start to their decades-long lifespans.

9. Upis Beetles (Upis ceramboides)

Upis beetles, native to Alaska and other northern boreal forests, represent the most freeze-tolerant insect species known to science. These remarkable beetles can survive temperatures as low as -100°C (-148°F) in laboratory settings—far below what they would naturally encounter even in the harshest Arctic winters. What makes Upis beetles truly exceptional is that they accomplish this feat without producing glycerol or other common cryoprotectants used by most freeze-tolerant organisms. Instead, these beetles employ a unique mechanism using specialized proteins that manage ice crystal formation, ensuring that ice forms between cells rather than within them, preventing cellular damage. Additionally, they produce xylomannan, a complex molecule that stabilizes cell membranes during freezing. During winter months, Upis beetles can remain completely frozen for over six months, with no heartbeat, respiration, or detectable metabolism. When spring arrives, they thaw gradually and resume activity with no apparent ill effects, making them one of nature’s most remarkable cold-surviving specialists.

8. Antarctic Nematodes (Plectus antarcticus)

Antarctic nematodes represent some of the southernmost permanent animal residents on Earth, surviving in one of the planet’s most unforgiving environments. These microscopic roundworms, particularly Plectus antarcticus, have evolved extraordinary mechanisms to endure the extreme freeze-thaw cycles of the Antarctic continent. When faced with freezing conditions, these nematodes enter a state called anhydrobiosis, where they lose up to 99% of their body water through a controlled dehydration process. Without sufficient water for ice to form, their cells are protected from the physical damage typically caused by ice crystals. Antarctic nematodes also produce trehalose and special proteins that preserve their cellular structures during freezing. What makes these tiny creatures especially remarkable is their ability to survive repeated freeze-thaw cycles that can occur quickly during Antarctic summer days, when temperatures may briefly rise above freezing before plunging again. Research has shown these nematodes can survive in a frozen state for decades, possibly even centuries, making them one of the most enduring multicellular life forms on the planet.

7. Eastern Box Turtles (Terrapene carolina carolina)

Eastern box turtles demonstrate an impressive ability to survive partial freezing that sets them apart from many other reptiles. While not as freeze-tolerant as wood frogs or painted turtle hatchlings, adult eastern box turtles can endure having up to 58% of their body water converted to ice during winter hibernation. When temperatures drop, these terrestrial turtles bury themselves in soil and leaf litter, where they enter a state of brumation (reptilian hibernation). As their body begins to freeze, they mobilize glucose and glycerol from liver glycogen stores, distributing these natural antifreeze compounds throughout their tissues. What makes their adaptation particularly interesting is that they maintain just enough unfrozen fluid in their circulatory system to allow minimal cellular processes to continue, even as much of their peripheral tissues freeze solid. Their hearts may beat as infrequently as once every 5-10 minutes during this state. Eastern box turtles can survive in a partially frozen state for several weeks, with documented cases of individuals surviving after being found completely encased in ice. When temperatures rise, they thaw gradually and resume normal activity, often with no lasting damage from their frozen experience.

6. Siberian Salamanders (Salamandrella keyserlingii)

The Siberian salamander has earned a legendary status among amphibians for its extraordinary cold tolerance. Native to the harsh environments of Siberia, these salamanders can survive in a frozen state for decades, with anecdotal reports suggesting they’ve been found alive in ancient permafrost dating back 100 years or more—though these extreme claims remain scientifically unverified. What has been confirmed is their remarkable ability to endure temperatures as low as -45°C (-49°F) by allowing up to 65% of their body water to freeze. Unlike many freeze-tolerant animals that rely primarily on glucose as a cryoprotectant, Siberian salamanders produce a complex mixture of protective compounds, including glycerol, sorbitol, and specialized proteins that both prevent cellular damage and repair it during thawing. These salamanders have also developed specialized adaptations in their cell membranes that maintain integrity during the physical stress of freezing. Perhaps most impressively, even their brain tissue can tolerate freezing without permanent damage, allowing complete recovery of neurological function after thawing. This combination of adaptations makes the Siberian salamander one of the most cold-hardy vertebrates on Earth.

5. Brine Shrimp (Artemia salina)

Brine shrimp, commonly known as sea monkeys when sold as novelty pets, possess remarkable abilities to survive extreme conditions, including freezing. Unlike many animals on this list that survive as adults, brine shrimp endure freezing primarily in their cyst stage—a dormant embryonic form. When environmental conditions deteriorate, female brine shrimp switch from producing actively swimming nauplii (larvae) to producing encysted embryos that enter a state called diapause. These cysts contain embryos with metabolism reduced to virtually undetectable levels, and they develop a tough outer shell that provides exceptional protection. The cysts produce large amounts of trehalose, which replaces water in their cells and stabilizes proteins and membranes during freezing. In this state, brine shrimp cysts can survive temperatures as low as -190°C (-310°F), exposure to vacuum, and even brief exposure to absolute zero. Scientists have successfully revived brine shrimp cysts after 10 years of continuous freezing. When placed in saltwater at room temperature, viable cysts hatch within 24-48 hours, with the embryos resuming development as if no time had passed—a remarkable demonstration of evolutionary adaptation to unpredictable environments.

4. Alaskan Darkling Beetles (Upis ceramboides)

Alaskan darkling beetles have evolved one of the most effective antifreeze systems in the natural world. These resilient insects survive the harsh Alaskan winters by employing a strategy that differs from many other freeze-tolerant organisms. Rather than producing glycerol or glucose as cryoprotectants, darkling beetles manufacture specialized antifreeze proteins that bind directly to ice crystals, preventing them from growing larger and damaging cells. These proteins, called thermal hysteresis factors, create a difference between the freezing and melting points of water within their bodies—a phenomenon rarely observed in nature. Additionally, darkling beetles produce xylomannan, a unique molecule that stabilizes cell membranes at extremely low temperatures. What makes these beetles truly extraordinary is their ability to survive temperatures as low as -60°C (-76°F) in their natural environment, with laboratory tests showing survival at even lower temperatures. During winter months, darkling beetles remain in a frozen state beneath tree bark or in leaf litter, completely immobile with no detectable metabolism. When spring arrives, they gradually thaw and resume activity with remarkable resilience, having spent months in what amounts to suspended animation.

3. Arctic Springtails (Megaphorura arctica)

Arctic springtails represent some of the most abundant animals in polar soil ecosystems, thriving where few other arthropods can survive thanks to their sophisticated freeze-avoidance strategies. Unlike many animals on this list that tolerate freezing, Arctic springtails employ a different approach—they remain unfrozen even when environmental temperatures plummet far below 0°C (32°F). These tiny hexapods accomplish this through a process called cryoprotective dehydration. As soil begins to freeze around them, the higher vapor pressure of supercooled water in their bodies compared to the surrounding ice causes water to gradually leave their bodies. They essentially dehydrate themselves in response to freezing conditions, removing enough water that what remains cannot form damaging ice crystals. Simultaneously, they produce trehalose and other cryoprotectants that replace the lost water, protecting cellular structures and maintaining the integrity of sensitive proteins and membranes. Arctic springtails can survive temperatures below -25°C (-13°F) in this desiccated state, with their metabolism slowed to barely perceptible levels. When conditions warm, they rapidly rehydrate and resume normal activity within hours. This specialized adaptation allows Arctic springtails to remain active deeper into the winter than most other invertebrates and emerge earlier in spring, giving them access to food resources when competitors remain dormant.

2. Gray Tree Frogs (Hyla versicolor)

Gray tree frogs demonstrate one of the most impressive freeze-tolerance adaptations among North American amphibians, rivaling the better-known wood frogs in their cold-surviving abilities. These arboreal frogs can survive having up to 65% of their body water converted to ice for periods exceeding weeks. As temperatures drop below freezing, gray tree frogs produce massive amounts of glycerol—up to 20% of their total body fluid volume can consist of this cryoprotectant, one of the highest concentrations observed in any freeze-tolerant vertebrate. What makes their adaptation particularly remarkable is that they maintain small pockets of unfrozen solution around vital organs, allowing minimal but critical metabolic processes to continue even while most of their body is frozen solid. Additionally, gray tree frogs have developed specialized adaptations in their skin that allow rapid gas exchange during the thawing process, enabling quick resumption of breathing even before their lungs become fully functional. Unlike many freeze-tolerant animals that hibernate in soil or under leaf litter, gray tree frogs often overwinter in tree hollows or under bark, exposing them to more extreme temperature fluctuations. This has driven the evolution of their ability to survive multiple freeze-thaw cycles in a single winter without accumulating damage, a remarkable feat of physiological resilience.

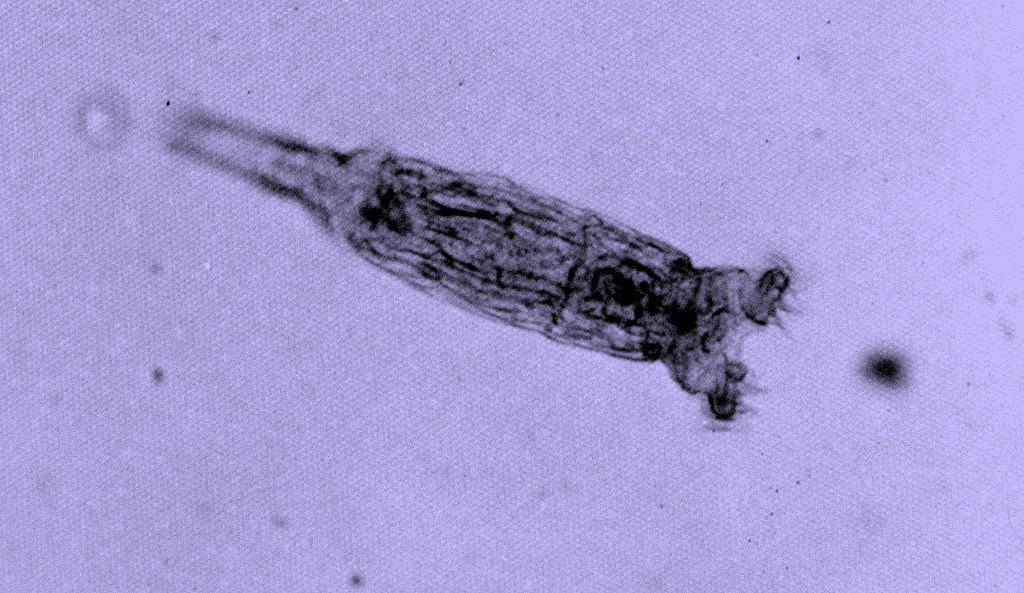

1. Rotifers (Bdelloidea)

Bdelloid rotifers, microscopic aquatic animals, display perhaps the most extraordinary long-term survival abilities of any animal on Earth. These tiny multicellular organisms, typically less than a millimeter long, can survive complete desiccation (anhydrobiosis) and freezing (cryobiosis) for astonishing periods. In 2021, scientists successfully revived bdelloid rotifers that had been frozen in Siberian permafrost for 24,000 years—the longest documented case of cryptobiosis leading to successful revival in any animal. When facing freezing conditions, rotifers enter a contracted state called a tun, where they lose over 95% of their body water through controlled dehydration. They produce trehalose and specialized heat-shock proteins that preserve the structural integrity of their cellular components and DNA during both freezing and thawing. What makes rotifers particularly fascinating is that they are among the few animals that reproduce exclusively through parthen

Conclusion:

In the most extreme environments on Earth, life has not only found a way to persist—it has mastered the art of pausing itself in time. From the microscopic tardigrades to the resilient wood frogs and Arctic caterpillars, these remarkable creatures reveal the astonishing diversity of strategies nature has evolved to survive the lethal grip of freezing temperatures. Their ability to suspend metabolism, protect delicate cells, and awaken after months—or even millennia—of frozen slumber challenges our understanding of life’s limits. Studying these incredible adaptations not only deepens our appreciation for the resilience of life on Earth but also opens new frontiers in fields like cryobiology, medicine, and space exploration. These masters of survival remind us that even in the harshest conditions, life finds a way to endure, adapt, and ultimately, thrive.

- 14 Creatures That Can Freeze and Thaw Back to Life - August 9, 2025

- 10 Animals That Risked Their Lives to Save Humans - August 9, 2025

- 14 Reasons Why Bears Are Afraid of Humans (Most of the Time) - August 9, 2025