In the vast diversity of life on Earth, evolution has taken many fascinating paths. While most vertebrates and many invertebrates rely heavily on vision, numerous creatures have evolved to thrive without eyes or with extremely reduced visual capabilities. These remarkable animals have developed alternative sensory systems that allow them to navigate their environments, find food, avoid predators, and even communicate. From the lightless depths of caves to the dark ocean floors, and even in environments where eyes would seem advantageous, these eyeless creatures demonstrate nature’s incredible adaptability. Let’s explore 14 fascinating animals that prove eyes aren’t always necessary for evolutionary success.

14. Mexican Blind Cavefish (Astyanax mexicanus)

The Mexican blind cavefish represents one of the most studied examples of evolutionary eye loss. These remarkable fish begin life with eye primordia (early developmental eye structures), but during development, the eyes degenerate and are eventually covered by skin. What makes these fish particularly fascinating to scientists is that they’re the same species as the surface-dwelling Mexican tetra, which has fully functional eyes. When populations became trapped in caves thousands of years ago, maintaining eyes in complete darkness was energetically costly and unnecessary, leading to their regression. Instead, these fish have developed an enhanced lateral line system—rows of pressure-sensitive organs along their bodies that detect changes in water pressure and movement. They’ve also evolved a higher number of taste buds and improved olfactory capabilities, allowing them to effectively locate food in total darkness. This makes them a prime example of regressive evolution, where traits are lost when they no longer provide survival advantages.

13. Star-Nosed Mole (Condylura cristata)

While star-nosed moles technically have eyes, they’re so small and underdeveloped that these creatures effectively navigate their world without vision. What makes these North American mammals truly extraordinary is their bizarre star-shaped nose—an organ unlike anything else in the animal kingdom. This distinctive appendage consists of 22 fleshy tentacles arranged in a circle around the nostrils, containing over 25,000 minute sensory receptors called Eimer’s organs. This sensory powerhouse makes the star-nosed mole’s nose the most sensitive touch organ known in any mammal. The mole can touch up to 12 objects per second with its star, creating a detailed tactile map of its surroundings. This remarkable adaptation allows these creatures to detect, identify, and consume prey faster than the human eye can follow—often in less than 120 milliseconds. Living in wet, underground tunnels where vision would provide little advantage, these moles have evolved a far more useful sensory system for their environment.

12. Olm (Proteus anguinus)

Often called the “human fish” due to its pinkish, flesh-colored skin, the olm is a permanently aquatic salamander that inhabits the underground caves of the Dinaric Alps in southeastern Europe. These bizarre amphibians begin life with small, underdeveloped eyes, but as they mature, their eyes regress and become covered by skin, rendering them functionally blind. Olms have evolved to live in complete darkness, developing heightened non-visual senses to compensate. They possess an extraordinary sense of smell, capable of detecting minute food particles in water. Their skin contains sensory cells that can detect light even when their eyes cannot, helping them avoid exposure to potentially harmful UV radiation. Perhaps most impressively, olms can sense the Earth’s magnetic field, aiding in navigation through complex cave systems. With a lifespan potentially exceeding 100 years and the ability to go without food for up to a decade by reducing their metabolism, these remarkable creatures have perfected the art of surviving in one of Earth’s most challenging environments without the need for vision.

11. Eyeless Shrimp (Rimicaris exoculata)

Deep in the hydrothermal vents of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge lives one of the ocean’s most fascinating creatures—the eyeless shrimp (Rimicaris exoculata). These shrimp form massive swarms around black smoker chimneys, where temperatures can exceed 350°C (662°F). Despite their name, these shrimp haven’t entirely lost their visual organs; rather, they’ve radically repurposed them. Instead of conventional eyes, they possess a dorsal organ containing light-sensitive cells that can detect the faint thermal radiation from the hydrothermal vents. This adaptation allows them to stay within the narrow habitable zone around the vents—close enough to harvest the chemosynthetic bacteria they depend on for food, but not so close that they’d be cooked by the superheated water. Beyond this specialized thermal detection system, these shrimp navigate using chemosensory organs that detect chemical gradients in the water. Their remarkable adaptations demonstrate how visual systems can evolve into something entirely different when traditional eyes no longer serve a useful purpose in extreme environments.

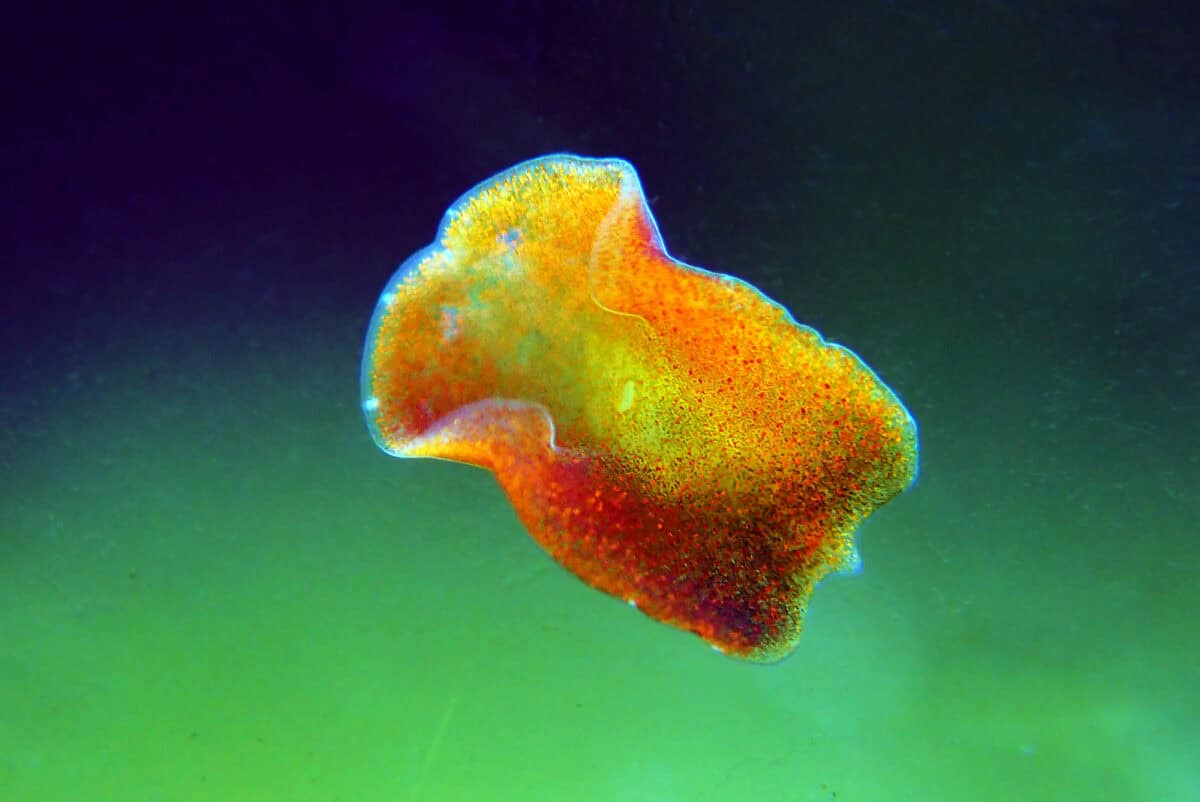

10. Sea Pork (Tunicates)

Despite their somewhat unappetizing name, sea porks or tunicates are fascinating marine creatures that undergo one of the most dramatic metamorphoses in the animal kingdom. Young tunicate larvae actually possess a primitive eye spot and a nerve cord, making them look more like tiny tadpoles than their adult forms. However, during metamorphosis, these mobile larvae attach to a substrate and undergo a radical transformation—reabsorbing their notochord, nerve cord, and eye spot to become sedentary filter-feeders. The adult sea pork exists as a blob-like colony of individuals encased in a firm, rubbery tunic, with no visual capabilities whatsoever. Instead of sight, adult tunicates rely entirely on chemical and tactile sensory systems to monitor water quality and control their water-filtering rate. Remarkably, these seemingly simple creatures are more closely related to vertebrates (including humans) than to other invertebrates, representing a fascinating evolutionary branch where complex structures like eyes were developed and then discarded when they no longer served a purpose.

9. Texas Blind Salamander (Eurycea rathbuni)

The Texas blind salamander is a striking example of cave adaptation, with its translucent, pinkish-white skin through which its internal organs are visible. Endemic to the waters of the Edwards Aquifer in San Marcos, Texas, these rare amphibians have evolved in complete darkness for so long that their eyes have regressed to mere dots beneath layers of skin. Despite their blindness, these salamanders are effective predators, capturing small aquatic invertebrates with remarkable precision. They’ve developed elongated limbs and a flattened snout that contains numerous sensory organs, allowing them to detect minute vibrations and chemical signals in the water. Their external gills, which appear as bright red feathery structures on their heads due to visible blood vessels, also function as sensory organs that help monitor water quality and detect prey. The salamander’s entire body is covered with specialized sensory cells that create a three-dimensional awareness of their surroundings far more useful in their environment than eyes would be. Their successful adaptation to subterranean life highlights nature’s ability to find sensory solutions that transcend traditional vision.

8. Naked Mole-Rat (Heterocephalus glaber)

The naked mole-rat might be known for its wrinkled, hairless appearance, but its sensory adaptations are equally remarkable. Living in extensive underground tunnel systems throughout parts of East Africa, these eusocial mammals have eyes so tiny and underdeveloped that they’re practically blind. Their eyes are often covered by a layer of skin and function primarily for light detection rather than forming images. To compensate for their poor vision, naked mole-rats have developed extraordinary alternative senses. Their large, sensitive front teeth can function as a “sixth sense,” detecting subtle vibrations and textures as they navigate through tunnels. Their whiskers and body hairs, though sparse, are highly sensitive to touch and air movements. Perhaps most remarkably, naked mole-rats have evolved specialized chemosensory neurons that allow them to detect subtle chemical cues from colony members, helping maintain their complex social structure where individuals recognize their queen and hundreds of colony mates. Their ability to thrive in underground environments with minimal oxygen, resist cancer, and feel little pain further demonstrates how these creatures have evolved far beyond the limitations of poor eyesight.

7. Blind Legless Lizards (Amphisbaenia)

Amphisbaenians, commonly known as worm lizards, are among the most specialized reptiles on Earth. Despite superficially resembling earthworms or snakes, they belong to a distinct group of squamates that diverged from other lizards over 150 million years ago. These remarkable reptiles have evolved for a fossorial (burrowing) lifestyle, with most species lacking external eyes entirely or having them reduced to tiny spots hidden beneath scales. Their skull is densely ossified and often shovel-shaped, serving as a powerful digging tool as they create tunnels through soil. Most species lack external ears and have lost their limbs entirely, although a few retain small front legs. To navigate their underground world, amphisbaenians rely primarily on their highly sensitive skin and specialized scales that detect vibrations, temperature changes, and chemical signals. Their unique ring-shaped body segments allow them to move through soil using an accordion-like motion called concertina locomotion or through more direct forward pushing. With approximately 190 species living on several continents, these specialized reptiles demonstrate how successful eye loss can be when accompanied by adaptations better suited to a subterranean lifestyle.

6. Blind Springtails (Folsomia candida)

Springtails are tiny hexapods that represent some of the most abundant arthropods on Earth, with some soil samples containing tens of thousands per square meter. While many springtail species possess simple eyespots, several cave-dwelling and soil-dwelling species, like Folsomia candida, have completely lost their visual organs. These minuscule creatures—typically measuring less than 2mm in length—navigate their world entirely through chemical and tactile senses. Their most distinctive feature is the furcula, a tail-like appendage folded under their abdomen that can be rapidly extended to launch the springtail several centimetres into the air—an impressive distance considering their tiny size. This mechanism serves as an emergency escape response triggered by sensory hairs that detect predator movements. Without eyes, blind springtails have developed extraordinarily sensitive antennae containing various specialized sensory organs that detect humidity, temperature, air currents, and chemical signals. Their success is evident in their ubiquity; these eyeless creatures are found on every continent, including Antarctica, and play crucial roles in soil ecosystems by breaking down organic matter and controlling microbial populations.

5. Blind Snakes (Typhlopidae)

Blind snakes comprise a diverse family of small, fossorial serpents found throughout tropical and subtropical regions worldwide. Despite their name, most blind snakes aren’t completely eyeless—rather, they possess severely reduced eyes covered by scales that can only detect light versus dark. These specialized reptiles have evolved numerous adaptations for their underground lifestyle. Their cylindrical bodies are covered in smooth, glossy scales that reduce friction while moving through soil, and their heads feature reinforced skulls for burrowing. Unlike their more familiar snake relatives, blind snakes possess solid, non-movable jaws adapted for their specialized diet of ant and termite larvae, eggs, and pupae. Many species have developed glands that secrete a substance mimicking the pheromones of their prey, allowing them to infiltrate ant and termite colonies without being attacked. When threatened, some blind snakes have a unique defensive behaviour: they can stiffen part of their tail to resemble their head, confusing predators about which end to the attack. This remarkable group, comprising over 400 species across several families, demonstrates how vision becomes secondary when other senses—particularly chemical detection—provide more valuable information in specialized habitats.

4. Eyeless Spiders (Sinopoda scurion)

Discovered in Laos in 2012, Sinopoda scurion became the first known completely eyeless species among huntsman spiders—a family typically characterized by their excellent vision and active hunting style. This remarkable cave-dwelling arachnid represents a perfect example of regressive evolution, where features become reduced or disappear when they no longer provide survival advantages. Unlike surface-dwelling huntsman spiders that possess eight eyes arranged in two rows, S. scurion has completely lost all visual organs, with no external trace of eyes on its pale, yellowish-brown body. Instead, this spider has developed extraordinarily sensitive leg hairs called trichobothria that detect the slightest air movements, allowing it to perceive approaching prey or predators. Its pedipalps—appendages near the mouth—contain dense chemoreceptors that analyze chemical signatures in its environment, essentially “tasting” the air and surfaces it touches. The discovery of this eyeless hunter in Laotian caves highlights how even predators from families that typically rely heavily on vision can adapt to light-deprived environments by enhancing other sensory systems, demonstrating the remarkable plasticity of arachnid evolution.

3. Blind Termites (Isoptera)

The vast majority of termite species have worker and soldier castes that completely lack eyes, representing some of the most successful eyeless creatures on the planet. While termite reproductive alates (the winged forms that leave the nest to establish new colonies) possess compound eyes for their brief above-ground phase, the workers and soldiers that comprise the bulk of a colony’s population are entirely blind. These industrious insects have evolved to navigate their dark, underground world using an impressive array of alternative senses. Their antennae contain specialized receptors that detect subtle chemical trails, allowing workers to follow pheromone paths laid by their nestmates. The antennae also sense air currents, humidity levels, and physical obstacles, creating a detailed picture of their surroundings. Many species can detect vibrations through the soil or their nest structures, allowing for complex communication. Some soldiers have evolved enlarged mandibles or chemical defense mechanisms that are triggered by specialized sensory hairs detecting intruders. With over 3,000 species worldwide and colonies sometimes numbering in the millions, blind termites demonstrate that losing eyes is no impediment to ecological and evolutionary success when compensated by more relevant sensory specializations.

2. Blind Crayfish (Procambarus lucifugus)

The caves and aquifers of North America are home to several species of blind crayfish, with Procambarus lucifugus being one of the most well-studied examples. These pale, ghostly crustaceans have lost all pigmentation along with their eyes, adaptations to environments where neither protection from UV radiation nor visual hunting capabilities provide any advantage. In place of vision, blind crayfish have developed extraordinarily sensitive antennae and body hairs that detect water currents, pressure changes, and physical contact. Their first pair of walking legs, tipped with small pincers, serve as both manipulative tools and sensory probes, constantly sweeping the area ahead as they move. Chemical reception is perhaps their most important sense, with specialized organs detecting dissolved substances in minute concentrations, allowing them to locate food, identify potential mates, and recognize territory markers left by other crayfish. Research has shown that these crayfish can detect and respond to chemical signals at concentrations as low as a few molecules per liter of water. Their successful adaptation to subterranean aquatic environments has allowed blind crayfish species to survive for millions of years in geological isolation, even as their surface-dwelling relatives faced extinction events and habitat changes.

1. Flatworms (Planarians)

Planarians are free-living flatworms found in freshwater environments worldwide, and while some species possess simple eyespots for detecting light direction, many cave-dwelling species have lost these structures entirely. Even in sighted species, these primitive eye structures cannot form images but merely detect the presence and direction of light. What makes planarians remarkable is their extraordinary sensory compensation and regenerative abilities. Their bodies are covered with thousands of sensory cells that detect chemical signals, water currents, and physical contact, creating a comprehensive awareness of their surroundings without visual input. The front end of their flat bodies contains a high concentration of chemoreceptors that function similarly to taste and smell, allowing them to locate food with remarkable precision. Perhaps most impressively, these seemingly simple organisms possess complex learning capabilities despite lacking eyes and having a primitive nerve net rather than a centralized brain. They can be conditioned to respond to specific stimuli and retain this memory even after their bodies are cut in half and regenerated—a process that provides insights into how memories might be stored throughout body tissues rather than exclusively in the brain. Their success across various habitats, including completely dark cave systems, demonstrates the effectiveness of distributed sensory systems as an alternative to centralized visual processing.

Conclusion

The natural world is full of extraordinary adaptations, and the creatures featured in this article prove that eyes are far from essential for survival. Whether burrowing underground, navigating pitch-black cave systems, or thriving near scalding hydrothermal vents, these animals demonstrate that evolution can favor touch, smell, vibration, magnetoreception, and chemosensation oversight. In some cases, the loss of eyes is not a handicap but an evolutionary refinement—removing unnecessary complexity in favor of more effective alternatives for a given environment. These eyeless or near-eyeless species remind us that survival and success in nature depend not on having the most senses but on having the right ones for the job.

- Animals in Idaho - August 20, 2025

- 10 Mammals You Did not Know Could Swim - August 20, 2025

- 13 Fastest Insects in the World - August 20, 2025