In the shadowy depths of oceans, hidden caves, or even forest floors at night, nature reveals one of its most captivating phenomena: bioluminescence. This magical-seeming ability to produce light is not just beautiful but serves critical survival functions for the creatures that possess it. From attracting mates to confusing predators or illuminating prey, the ability to glow in the dark has evolved independently across different animal groups as a remarkable example of convergent evolution. Here, we explore 14 fascinating creatures that light up the darkness and the science behind their glow.

The Science of Bioluminescence

Before diving into specific creatures, it’s important to understand what makes these animals glow. Bioluminescence is a chemical process where light is produced through a reaction between a compound called luciferin and an enzyme called luciferase, with oxygen often serving as a catalyst. This reaction creates energy that’s released as light rather than heat—a process known as “cold light” because it’s nearly 100% efficient. Unlike fluorescence (where absorbed light is re-emitted) or phosphorescence (where light emission continues after exposure), bioluminescence requires no external light source. The colors produced—typically blues and greens in marine environments—have evolved to be visible at the depths where these creatures live, as these wavelengths travel farthest through water.

14. Fireflies Nature’s Light Show Orchestrators

Perhaps the most familiar bioluminescent creatures, fireflies (or lightning bugs) are beetles that use their light-producing organs located on their abdomens to create elaborate mating signals. Different firefly species have distinct flash patterns—some flash quick bursts while others produce longer glows or complex sequences. Males typically fly around flashing their signals, while females respond from perches on vegetation. The light produced is nearly 100% efficient, converting almost all energy into light rather than heat. Remarkably, some predatory female fireflies mimic the flash patterns of other species to lure males as prey, demonstrating how this light communication system has evolved into complex ecological relationships.

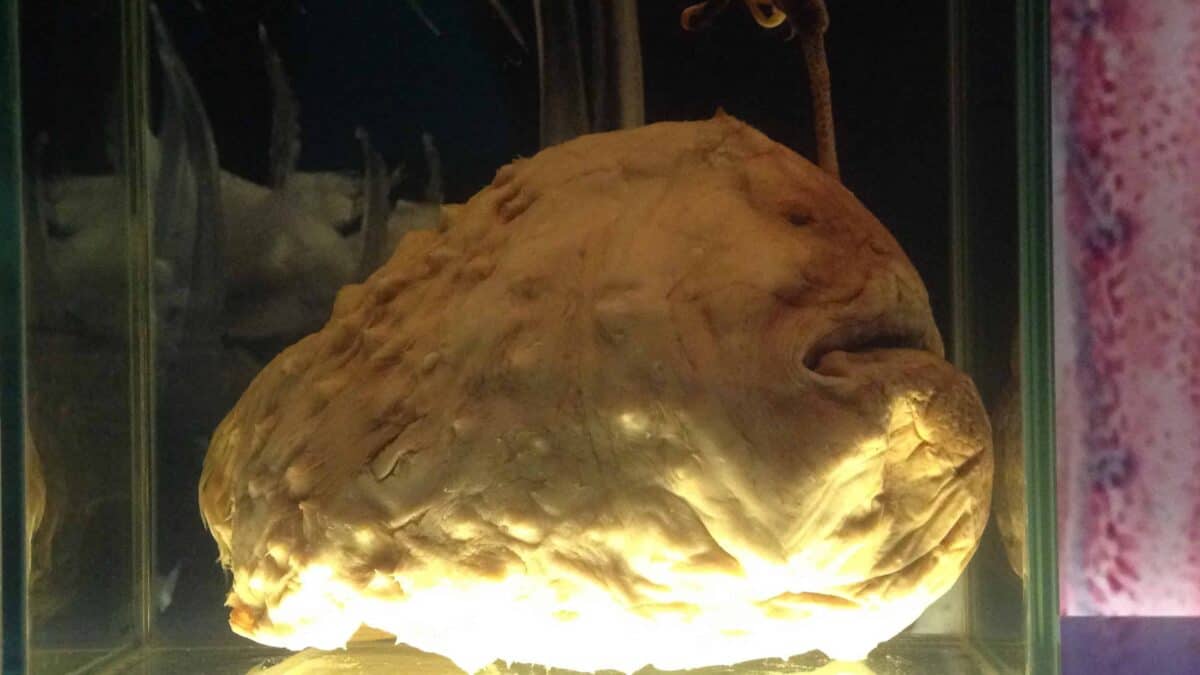

13. Deep Sea Anglerfish Deadly Lures in the Abyss

In the perpetual darkness of the deep sea, female anglerfish sport a bioluminescent lure that dangles from a modified dorsal fin spine above their enormous, fang-filled mouths. This fishing rod-like appendage (called an esca) contains light-producing bacteria that live symbiotically with the fish. The glowing lure attracts curious prey that mistake it for potential food or a small organism—only to suddenly find themselves becoming food instead. The symbiotic relationship is fascinating: the bacteria receive nutrients and a safe place to live, while the anglerfish gets a living light that requires no energy expenditure. Adding to their bizarre nature, male anglerfish are tiny parasites that permanently fuse to the female’s body, essentially becoming sperm-producing appendages.

12. Glowworms Cave Ceiling Constellations

Despite their name, glowworms aren’t worms at all—they’re the larvae of fungus gnats. The most famous are New Zealand’s Arachnocampa luminosa, which create spectacular displays in caves like Waitomo. These larvae hang sticky silk threads from cave ceilings and use their blue-green tail lights to attract flying insects. When prey becomes entangled in these threads, the glowworm pulls up its fishing line and consumes its catch. What makes this hunting strategy particularly effective is that flying insects are naturally attracted to light, and in the complete darkness of caves, even the faint glow of these larvae acts as an irresistible beacon. The hungrier the glowworm, the brighter it glows, creating a direct relationship between its nutritional needs and luminous output.

11. Dinoflagellates Ocean Sparklers

These single-celled marine plankton are responsible for the breathtaking phenomenon of “sea sparkle” or bioluminescent bays, where disturbed water glows blue at night. When agitated by movement—whether from breaking waves, a swimming fish, or a kayak paddle—these microscopic organisms emit brief flashes of blue light. Scientists believe this flash serves as a “burglar alarm”—the light startles predators or attracts larger predators that might eat the organisms threatening the dinoflagellates. Some species like Noctiluca scintillans can gather in such concentrations that beaches appear to be lined with blue fire when waves break at night. While beautiful, some dinoflagellate blooms can also be associated with red tides that produce toxins harmful to marine life and humans.

10. Comb Jellies Rainbow Light Displays

Comb jellies, or ctenophores, offer a unique twist on underwater illumination. Unlike true jellyfish, these transparent, gelatinous animals combine bioluminescence with iridescence to create spectacular rainbow light displays. Their bodies feature rows of cilia (hair-like structures) that scatter light into prismatic colors as they move through the water. When disturbed, many species can also produce blue-green bioluminescent flashes. This dual lighting capability serves multiple purposes—the iridescent rainbow effect helps camouflage them in changing light conditions, while the bioluminescent flash, like in many marine creatures, may startle predators or attract larger animals that might prey on their attackers. Some deep-sea species like Beroe have bioluminescent particles distributed throughout their bodies, allowing them to light up entirely when disturbed.

9. Foxfire Fungi Forest Floor Illuminators

Walking through old-growth forests at night, particularly in warm, humid regions, you might encounter an eerie green-blue glow emanating from decaying logs. This phenomenon, known as “foxfire,” comes from bioluminescent fungi, with Armillaria species (honey fungi) being among the most common. Unlike animals that typically use bioluminescence for communication or predation, the exact reason fungi glow remains somewhat mysterious. Leading theories suggest the light attracts insects that help spread fungal spores, or that it’s a byproduct of lignin-degrading oxidative enzymes that help the fungi break down wood. The glow is most visible during the active growth phase, with mycelium (the vegetative part of the fungus) producing a steady, ghostly light that once helped travelers navigate forests before electric lighting. Some cultures have attached supernatural significance to these glowing fungi, associating them with spirits or fairy lights.

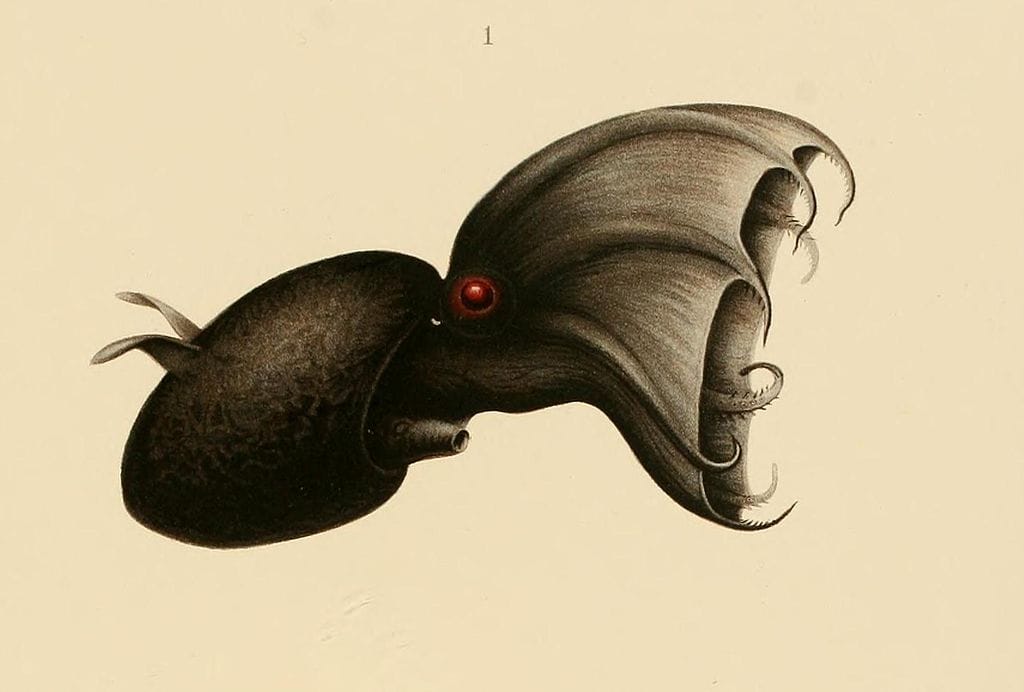

8. Vampire Squid Masters of Counterillumination

Despite its intimidating name, the Vampire Squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis, literally “vampire squid from hell”) is actually a gentle deep-sea dweller that employs bioluminescence in multiple sophisticated ways. Living in the oxygen-minimum zone between 600-900 meters deep, it possesses photophores (light-producing organs) covering its body that allow for counterillumination—matching the faint light from above to eliminate its silhouette from below. When threatened, it can turn these lights on and off in complex patterns to confuse predators, or even detach the glowing tips of its arms as a distraction while it escapes. Perhaps most impressively, it can also secrete bioluminescent mucus clouds that glow for up to 10 minutes, effectively creating a diversion that buys time for escape. This multimodal approach to light production makes the Vampire Squid one of the most versatile bioluminescent creatures in the ocean.

7. Railroad Worms Light-Up Locomotives

Railroad worms are beetle larvae (Phrixothrix) that earned their name from their distinctive appearance—they display red lights on their heads and a series of greenish-yellow lights along their bodies that resemble the windows of a moving train at night. What makes these creatures particularly remarkable is their ability to produce two different colors of bioluminescence simultaneously—something rare in the animal kingdom. The red head light (which produces the longest wavelength of any known bioluminescent creature) serves as a warning to predators, signaling that the larvae contain toxic compounds. The greenish-yellow lateral lights may help with navigation or attracting prey. Found primarily in South America, these beetles demonstrate how bioluminescence can serve multiple functions even within a single organism, with different light colors evolved for separate survival advantages.

6. Crystal Jellies Transparent Glowing Beauties

The crystal jelly (Aequorea victoria) is a transparent, delicate creature that produces a cyan-blue glow around the rim of its bell. More than just a beautiful marine organism, this jellyfish has made an enormous contribution to science—the Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) isolated from these jellies revolutionized biological research and earned its discoverers the 2008 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Scientists now use GFP as a biological marker to study everything from cancer cell development to neural connections in the brain. In its natural state, the crystal jelly’s luminescence serves both defensive and feeding purposes. When disturbed, the rim lights up in a circular pattern that may confuse predators, and the glow can attract smaller organisms that become prey. Unlike many other bioluminescent creatures, crystal jellies can produce light without requiring a separate enzyme reaction, making their light-production system uniquely efficient.

5. Lanternfish Deep-Sea Communicators

Lanternfish (Myctophidae) are among the most abundant vertebrates on Earth, making up an estimated 65% of all deep-sea fish biomass. These small fish (typically 3-6 inches long) feature distinctive patterns of photophores (light-producing organs) along their undersides and sides. These patterns are species-specific and act like biological ID badges, helping the fish recognize potential mates in the darkness. They also use counterillumination—matching downwelling light from above to conceal their silhouettes from predators lurking below. Each night, lanternfish participate in one of the planet’s largest daily migrations, rising from depths of 300-1,500 meters to surface waters to feed under cover of darkness, then returning to deeper waters at dawn. This vertical migration is so massive that it once confused military sonar operators who mistook the rising mass of fish for a “false seafloor” that seemed to rise each night—a testament to the incredible abundance of these glowing creatures.

4. Cookiecutter Sharks Glowing Ambush Predators

The cookiecutter shark (Isistius brasiliensis) employs one of the most devious uses of bioluminescence in the animal kingdom. This small, cigar-shaped shark (typically about 20 inches long) has photophores covering its entire body except for a dark band around its neck. When viewed from below against the light filtering down from the surface, this creates an optical illusion where the dark collar looks like a small fish, while the glowing body blends into the background light. Larger predatory fish or marine mammals mistake this “small fish” silhouette for prey and approach—only to have the shark quickly turn and take a cookie-cutter-shaped plug of flesh from the surprised predator. This parasitic feeding strategy is remarkably effective, with cookiecutter bite marks found on everything from tuna and dolphins to submarines and underwater cables. Their bioluminescence thus serves as an ingenious form of aggressive mimicry, turning the tables on potential predators.

3. Millipedes Glowing Warning Systems

Several species of millipedes, particularly in the genus Motyxia found in California, glow with a blue-green light that serves as a warning signal to potential predators. Unlike many bioluminescent creatures that use their light for communication or hunting, these millipedes use bioluminescence purely as a defense mechanism. The glow advertises their ability to produce toxic hydrogen cyanide when threatened—essentially functioning as a “don’t eat me” sign that predators learn to avoid. Research has shown that predation attempts on these millipedes increase significantly when their bioluminescence is artificially blocked, confirming the effectiveness of this warning system. Interestingly, these millipedes are blind, so they can’t see their own glow—it evolved solely for communication with other species. This example of aposematic (warning) coloration through light rather than pigments demonstrates yet another evolutionary application of bioluminescence as a survival strategy.

2. Flashlight Fish Reef Communicators and Hunters

Flashlight fish (family Anomalopidae) harbor colonies of bioluminescent bacteria in special light organs located beneath their eyes. Unlike many deep-sea bioluminescent creatures, some flashlight fish species inhabit relatively shallow coral reef areas, using their bacterial headlights to navigate and hunt at night. They can control their light emission by either covering the light organ with a specialized lid (like closing a shutter) or by controlling blood flow to the bacteria. These fish use their lights in surprisingly sophisticated ways—flashing in unison when schooling to confuse predators, using the light to attract plankton, or illuminating potential prey. Some species engage in “blink-and-run” behavior, where they momentarily flash their lights and then quickly change position, making it difficult for predators to track them. The symbiotic relationship with their light-producing bacteria is so refined that the bacteria cannot survive outside the fish, and the fish cannot produce light without the bacteria—a fascinating example of co-evolution.

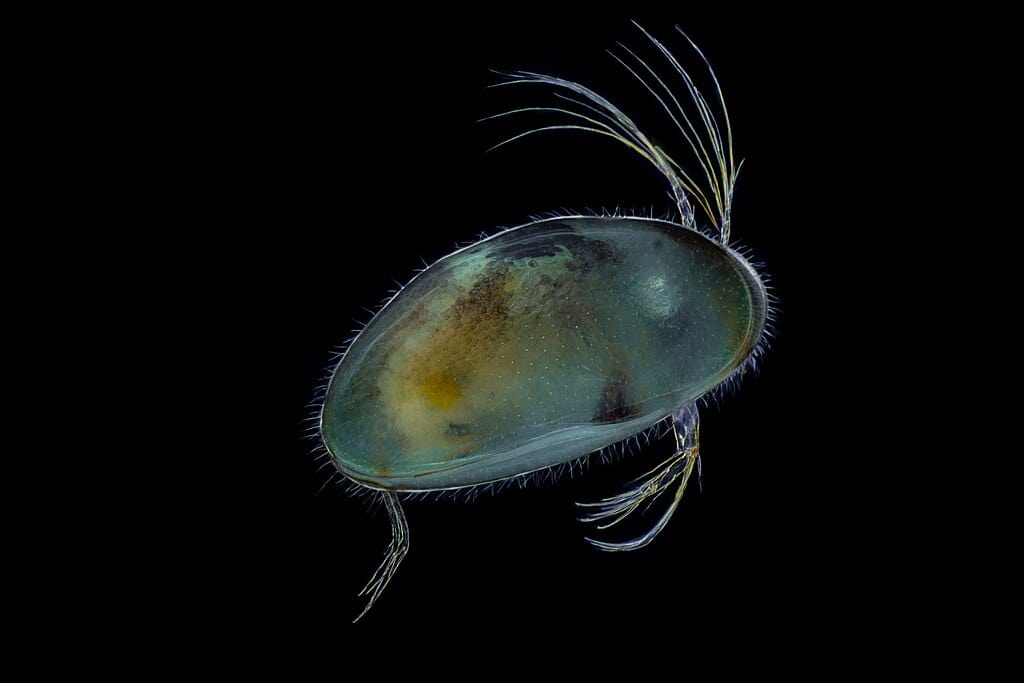

1. Ostracods Tiny Light Bomb Specialists

Ostracods, sometimes called seed shrimp, are tiny crustaceans that include some of the most spectacular bioluminescent displays in marine environments. Certain species, particularly in the Caribbean, release clouds of blue luminescent chemicals into the water as part of their mating displays. Males swim in distinctive patterns while releasing these “light bombs” that persist for several seconds to minutes, creating underwater light trails that attract females. Some species synchronize these displays to create complex patterns of light in the water column. Unlike most other bioluminescent creatures that keep their light-producing chemicals inside their bodies, ostracods eject their luciferin and luciferase into the water, where the reaction occurs externally. This extracellular bioluminescence requires producing significant amounts of these valuable compounds, which the ostracods then expend in a single display—an energetically costly but evidently effective reproductive strategy that creates one of nature’s most magical light shows.

Conclusion: The Evolutionary Significance of Nature’s Light Shows

The phenomenon of bioluminescence has evolved independently at least 40 times across the tree of life, highlighting its remarkable adaptive value. This convergent evolution demonstrates how the ability to produce light provides significant survival and reproductive advantages in various environments, particularly those with limited visibility. What makes bioluminescence particularly fascinating is how it illustrates the diverse solutions nature develops for similar challenges—whether attracting mates, finding prey, avoiding predators, or communicating with conspecifics. From microscopic marine plankton to complex vertebrates, the chemistry of light production has been refined through millions of years of natural selection. Beyond their ecological importance, bioluminescent organisms continue to inspire scientific breakthroughs, from the development of sensitive bioassays to applications in medical imaging and even potential solutions for sustainable lighting. As we continue to explore the darkest corners of our planet, we’ll likely discover even more creatures that have mastered the art of bringing light to the darkness, each with its own evolutionary story to tell.

- How the Bison Shaped North American Ecosystems - August 8, 2025

- 14 Creatures That Glow in the Dark And Why - August 8, 2025

- 13 Amphibians That Can Survive Freezing Temperatures - August 8, 2025