The animal kingdom is full of fascinating abilities, but few are as remarkable as autotomy—the capacity to voluntarily shed a body part and later regenerate it. Among reptiles, many lizard species have mastered this impressive survival technique, particularly when it comes to their tails. When threatened by predators, these resilient creatures can detach their tails as a distraction, allowing them to escape while the predator is preoccupied with the still-moving appendage. Even more impressive is what happens next: the regrowth of an entirely new tail. This regenerative ability varies across species in terms of speed, completeness, and the structure of the regenerated tail. Let’s explore 15 remarkable lizard species that demonstrate this evolutionary advantage and how their regenerative capabilities differ.

The Science Behind Tail Regeneration

Tail regeneration in lizards is a complex biological process that begins immediately after autotomy occurs. When a lizard’s tail detaches, it breaks along specialized fracture planes within the vertebrae. The wound quickly closes to prevent blood loss and infection, and a blastema forms—a mass of dedifferentiated cells that will eventually develop into the new tail. This regenerative capability is possible because certain lizard species retain stem cells in their tail tissues throughout their lives. However, the regenerated tail is typically not identical to the original. It often contains a cartilaginous rod instead of vertebrae and may have different coloration, scale patterns, and muscle arrangements. The entire process can take weeks to months depending on the species, age of the lizard, and environmental conditions such as temperature and food availability. This remarkable ability has made lizards important models for regenerative medicine research, as scientists hope to unlock secrets that might one day help humans regenerate damaged tissues and organs.

14. Green Anole (Anolis carolinensis)

The Green Anole, native to the southeastern United States, is perhaps one of the most studied lizards for tail regeneration. These small, emerald-colored lizards can shed their tails when grabbed by predators and begin regenerating a new one almost immediately. Research has shown that they can regrow their tails in approximately 60 days, though the replacement is never quite the same as the original. The regenerated tail contains a cartilaginous rod rather than vertebrae and has a slightly different coloration and scale pattern. What makes the Green Anole particularly interesting to scientists is that it was the first lizard to have its genome fully sequenced, allowing researchers to identify the specific genes activated during tail regeneration. This genetic information has proven invaluable for comparative studies with other regenerating species and potential applications in regenerative medicine.

13. Common House Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus)

The Common House Gecko, widely distributed throughout Asia and introduced to many parts of the world, exhibits impressive tail regeneration capabilities. These nocturnal climbers can shed their tails with minimal provocation and begin regenerating them within days. Their regenerated tails typically grow to about 70-80% of the original length and are often darker in color than the original. What’s remarkable about House Geckos is the speed of their regeneration—they can produce a functional replacement tail in just 30 days under optimal conditions. This rapid regeneration is particularly advantageous for these small geckos, as their tails serve important functions in fat storage and balance while climbing vertical surfaces. House Geckos have also adapted to living close to humans, which means their regenerative processes can often be observed in urban environments, making them accessible subjects for casual observation and citizen science projects.

12. Leopard Gecko (Eublepharis macularius)

The Leopard Gecko, a popular pet reptile native to arid regions of Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwestern India, has one of the most distinctive tail regeneration processes. Unlike many lizard species, Leopard Geckos use their thick tails primarily as fat storage organs, making them crucial for survival. When they shed their tails, they lose a significant energy reserve. The regenerated tail of a Leopard Gecko is typically shorter, thicker, and has a different pattern than the original. It also lacks the same fat storage capacity initially, although it improves over time. The regeneration process takes about 30-40 days, but full maturation of the new tail can take several months. Interestingly, if a Leopard Gecko loses only part of its tail, it may regenerate just the missing portion while retaining the original base. This partial regeneration capability demonstrates the sophisticated control mechanisms involved in their tissue regeneration process.

11. Western Fence Lizard (Sceloporus occidentalis)

The Western Fence Lizard, commonly found throughout western North America, demonstrates remarkable tail regeneration capabilities that vary based on age and environmental factors. These blue-bellied lizards can regenerate their tails in approximately 2-3 months, with younger individuals typically regenerating more quickly and completely than older ones. The regenerated tail of a Western Fence Lizard is usually shorter and has a different scale pattern than the original. One fascinating aspect of their regeneration is that the new tail often has different pigmentation, sometimes appearing more uniform in color rather than maintaining the intricate patterns of the original tail. Research has shown that Western Fence Lizards living in warmer climates tend to regenerate their tails faster than those in cooler regions, highlighting the influence of environmental temperature on the regenerative process. These lizards have also been subjects of studies examining how predation pressure affects the evolution of their regenerative capabilities across different habitats.

10. Tokay Gecko (Gekko gecko)

The Tokay Gecko, known for its distinctive blue-gray coloration with orange or red spots and its loud “to-kay” call, possesses impressive regenerative abilities despite its relatively large size among geckos. Native to Southeast Asia and parts of the Pacific, these geckos can grow up to 15 inches long, with their tails comprising nearly half their total length. When a Tokay Gecko drops its tail, the regeneration process is slower than in smaller gecko species, typically taking 3-4 months. However, the quality of regeneration is notable—the new tail develops similar (though not identical) coloration patterns to match the body, which is unusual among larger lizards. The regenerated tail contains a cartilaginous rod rather than true vertebrae and has slightly different muscular arrangements than the original. What makes Tokay Geckos particularly interesting for regeneration studies is that they demonstrate different rates of regeneration at different life stages, with juvenile geckos regenerating significantly faster than adults. This age-dependent variation provides insights into how regenerative capabilities change throughout the lifespan of these remarkable reptiles.

9. Crested Gecko (Correlophus ciliatus)

The Crested Gecko, endemic to New Caledonia and popular in the pet trade, presents a unique case among regenerating lizards—they cannot regrow their tails once lost. This makes them an interesting comparative study subject against other regenerating gecko species. When a Crested Gecko loses its tail, the wound heals completely, but no regeneration occurs, resulting in a smooth, rounded tail stub that remains for life. This characteristic is so distinctive that these geckos are sometimes called “frogbutts” in the pet community after they’ve lost their tails. Despite lacking regenerative abilities, Crested Geckos have evolved to function perfectly well without tails, showing no significant deficits in climbing, balance, or overall health after tail loss. This evolutionary adaptation suggests that for Crested Geckos, the metabolic cost of maintaining regenerative capabilities outweighed the benefits in their native habitat. The contrast between Crested Geckos and their regenerating relatives offers valuable insights into the evolution and genetics of regeneration, highlighting that this ability is not universal even within closely related lizard species.

8. Bearded Dragon (Pogona vitticeps)

Bearded Dragons, native to Australia and widely kept as pets, have limited tail regeneration capabilities compared to many other lizards. When a Bearded Dragon loses its tail, it can regrow a replacement, but the regenerated appendage is typically much shorter, lacks the distinctive spikes of the original, and often has a different coloration. The regeneration process is relatively slow, taking 3-4 months for partial regrowth. Unlike some smaller lizards that can drop their tails with minimal provocation, Bearded Dragons rarely autotomize their tails except under extreme stress or direct injury. This reluctance to shed may be related to the tail’s importance for fat storage and balance in these semi-arboreal lizards. Interestingly, the capacity for regeneration in Bearded Dragons appears to diminish with age—juveniles demonstrate better regenerative outcomes than adults. This age-dependent decline in regenerative ability makes them valuable models for studying how regenerative capacities change throughout an organism’s lifespan, potentially offering insights relevant to age-related healing impairments in humans.

7. Mediterranean House Gecko (Hemidactylus turcicus)

The Mediterranean House Gecko, which has been introduced to many parts of the world including the southern United States, demonstrates remarkable tail regeneration capabilities. These small, pale geckos can regenerate their tails in approximately 30-45 days, with the process accelerating in warmer temperatures. What makes their regeneration particularly interesting is the behavioral adaptation that accompanies it—immediately after losing their tail, these geckos typically become more cautious and limit their foraging range until regeneration is well underway. The regenerated tail of a Mediterranean House Gecko is usually shorter and has a slightly different scale pattern than the original. It also lacks the same fat storage capacity initially. Researchers have observed that Mediterranean House Geckos living in urban environments (where they’re often found on buildings) appear to have higher rates of tail regeneration than their rural counterparts, suggesting that urban pressures may select for enhanced regenerative capabilities. This makes them excellent subjects for studying how environmental factors influence regenerative outcomes.

6. Blue-tailed Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus)

The Blue-tailed Skink, named for the vivid blue tail coloration of juveniles, employs a fascinating strategy with its regenerative capabilities. The bright blue tail serves as a distraction for predators, drawing attention away from the skink’s vital body parts. When threatened, these North American natives can shed their tails, which continue to wiggle vigorously for several minutes after detachment, creating an effective diversion. Their regeneration process takes approximately 2-3 months, though the new tail never regains the brilliant blue coloration of the original juvenile tail. Instead, the regenerated tail typically matches the adult body coloration, which is usually brownish or bronze. Interestingly, Blue-tailed Skinks demonstrate different regeneration rates depending on the season, with faster regrowth occurring during warmer months when metabolism is higher and food is more abundant. Research has shown that these skinks can regenerate their tails multiple times throughout their lives, though each successive regeneration tends to be less complete than the previous one. This diminishing return on regeneration raises important questions about the energetic costs and evolutionary limits of this remarkable ability.

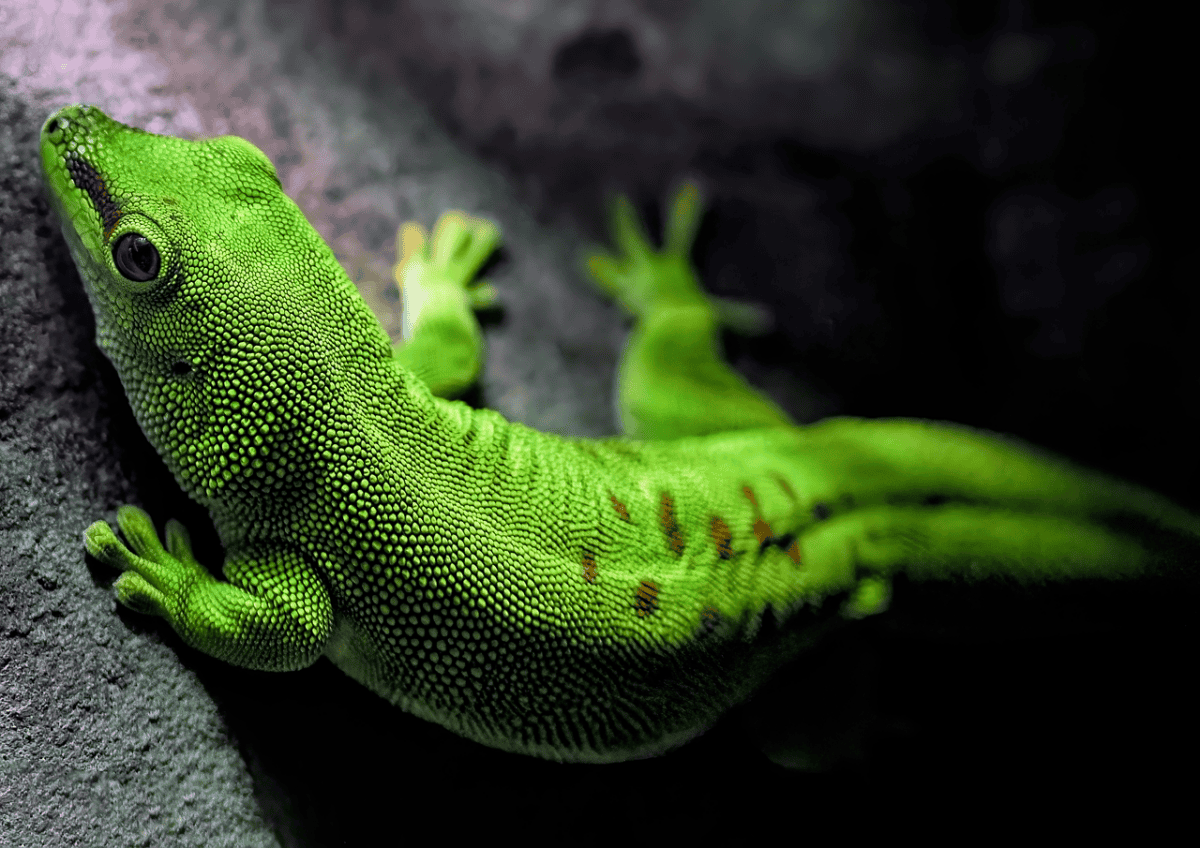

5. Day Gecko (Phelsuma spp.)

Day Geckos, comprising several species in the genus Phelsuma native to Madagascar and other Indian Ocean islands, are known for their vibrant coloration and remarkable regenerative abilities. Unlike most geckos which are nocturnal, Day Geckos are active during daylight hours, making their regenerative processes easier to observe in natural settings. When a Day Gecko loses its tail, it typically regenerates a new one in 30-60 days depending on the species, age, and environmental conditions. The regenerated tail often has slightly different coloration than the original—usually less vibrant and with altered patterns. One particularly interesting aspect of Day Gecko regeneration is their sensitivity to handling during the process. Stress can significantly slow regeneration, and attempting to handle these geckos while their tails are regrowing can even cause them to drop the partially regenerated tail, forcing them to restart the process. This extreme sensitivity highlights the physiological demands of regeneration and demonstrates how external stressors can impact complex biological restoration processes. Research on Phelsuma species has contributed significantly to our understanding of how stress hormones interact with and potentially inhibit regenerative mechanisms.

4. Texas Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma cornutum)

The Texas Horned Lizard, with its distinctive crown of horns and flat, toad-like body, has more limited tail regeneration capabilities compared to many other lizards. When these lizards lose their relatively short tails, they can regenerate a replacement, but the process is slower—typically taking 3-4 months—and the regenerated tail is often noticeably different from the original. The new tail is usually shorter, lacks the same scale pattern, and has a somewhat different shape. Unlike species that use tail autotomy as a primary defense mechanism, Texas Horned Lizards rely more on camouflage, playing dead, and their unique ability to squirt blood from their eyes to deter predators. This reduced reliance on tail autotomy may explain their more limited regenerative capabilities. Interestingly, research has shown that Texas Horned Lizards demonstrate better regeneration outcomes in habitats with fewer predators, suggesting that environmental pressures influence the evolution of regenerative capacities. As these lizards have become threatened in parts of their range due to habitat loss, understanding their regenerative limitations has become important for conservation efforts and captive breeding programs.

3. Five-lined Skink (Plestiodon fasciatus)

The Five-lined Skink, recognizable by the five light stripes running along its dark body and the bright blue tail of juveniles, demonstrates impressive tail regeneration capabilities. Native to eastern North America, these skinks can completely shed their tails when grabbed by predators, with the detached tail continuing to writhe and twitch for several minutes afterward—a highly effective distraction. The regeneration process takes approximately 2-3 months, with the new tail growing from a blastema that forms at the wound site. While the regenerated tail contains a cartilaginous rod rather than true vertebrae, it functions effectively for balance and locomotion. One fascinating aspect of Five-lined Skinks is the change in their regenerative capacity with age. Juveniles, with their eye-catching blue tails specifically evolved to attract predator attention away from vital body parts, regenerate more quickly and completely than adults. Research has also shown that these skinks can regenerate their tails multiple times if necessary, though subsequent regenerations are typically less perfect than the first. This ability to repeatedly replace a lost appendage throughout their lifetime represents a remarkable evolutionary adaptation and highlights the sophisticated nature of their regenerative mechanisms.

2. Italian Wall Lizard (Podarcis sicula)

The Italian Wall Lizard, a species native to Italy but introduced to multiple locations worldwide, has become an important model organism in regeneration studies due to its exceptional tail regeneration capabilities. These small, agile lizards can regenerate their tails in approximately 6-8 weeks, with the process being faster in juveniles and during warmer months. The regenerated tail contains a cartilaginous tube instead of vertebrae and has slightly different muscle arrangement and scale patterns. What makes Italian Wall Lizards particularly interesting to researchers is their demonstrated ability to adapt their regenerative processes to different environments. Studies of introduced populations in the United States have shown that these lizards can modify both the speed and quality of their tail regeneration based on local predation pressures and climate conditions. This adaptability suggests a genetic plasticity in their regenerative mechanisms that allows for rapid evolutionary responses to new selection pressures. Italian Wall Lizards have also been subjects of developmental biology research examining how regeneration recapitulates aspects of embryonic development, providing insights into the fundamental cellular mechanisms underlying tissue reconstruction.

1. Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris)

The Mourning Gecko presents a fascinating case in the study of reptile regeneration. These small geckos, native to the Indo-Pacific region but introduced worldwide, have two remarkable biological features that intersect with their regenerative abilities. First, they are parthenogenetic—all individuals are female and reproduce by creating clones of themselves without requiring fertilization. Second, they possess impressive tail regeneration capabilities, able to regrow a functional tail in approximately 30-45 days. The regenerated tail contains a cartilaginous rod instead of vertebrae and typically has slightly different coloration and patterning than the original. What makes Mourning Geckos particularly valuable for.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, the regenerative abilities of lizards highlight one of nature’s most astonishing survival strategies—autotomy followed by tail regrowth. This remarkable adaptation not only allows these reptiles to escape predation but also demonstrates a wide range of biological complexity and evolutionary fine-tuning across species. From the rapid regeneration of the Common House Gecko to the complete absence of regrowth in the Crested Gecko, each species showcases a unique evolutionary response to environmental pressures, ecological roles, and genetic constraints. Moreover, these natural phenomena provide valuable insights for scientific research, particularly in regenerative medicine, where understanding the mechanisms behind lizard tail regeneration could inform future breakthroughs in human tissue and organ repair. Ultimately, the study of tail regeneration in lizards is more than just a look at an impressive survival tactic—it’s a window into the potential of biological resilience and the secrets of regeneration itself.

- 14 Lizard Species That Can Regrow Their Tails - August 10, 2025

- Animal Rights Violation Issues in The United States - August 10, 2025

- 10 Times Steve Irwin Risked It All for Animals - August 10, 2025