Along the Pacific coastline, from Alaska to California, an underwater environmental success story is unfolding beneath the waves. Sea otters, those charismatic marine mammals known for floating on their backs and using rocks as tools, are doing far more than delighting wildlife enthusiasts—they’re helping to restore vital kelp forest ecosystems. These dense underwater forests, which once dominated nearshore Pacific waters, have faced dramatic decline in recent decades, with some regions losing more than 80% of their kelp coverage. The relationship between sea otters and kelp forests represents one of nature’s most fascinating examples of trophic cascades, where changes at one level of the food web ripple throughout the entire ecosystem. As sea otter populations recover from near-extinction, scientists are documenting remarkable recoveries in kelp forest health and biodiversity, showcasing how the restoration of a single species can transform entire marine ecosystems.

The Near-Extinction of Sea Otters

The saga begins with a tragedy that nearly erased sea otters from the planet. Prior to the maritime fur trade of the 18th and 19th centuries, an estimated 150,000 to 300,000 sea otters inhabited coastal waters from Japan to California. Their luxurious fur—the densest of any mammal at up to one million hairs per square inch—made them prime targets for hunters. By the early 1900s, only about 1,000-2,000 sea otters remained worldwide, scattered in 13 small colonies. The species was pushed to the brink of extinction, with entire regional populations completely wiped out. California’s sea otters, for instance, were thought extinct until a small group of about 50 individuals was discovered near Big Sur in 1938. This catastrophic population collapse would have profound and unexpected consequences for coastal ecosystems, as the absence of sea otters allowed their prey species to proliferate unchecked, setting the stage for dramatic changes to kelp forest habitats.

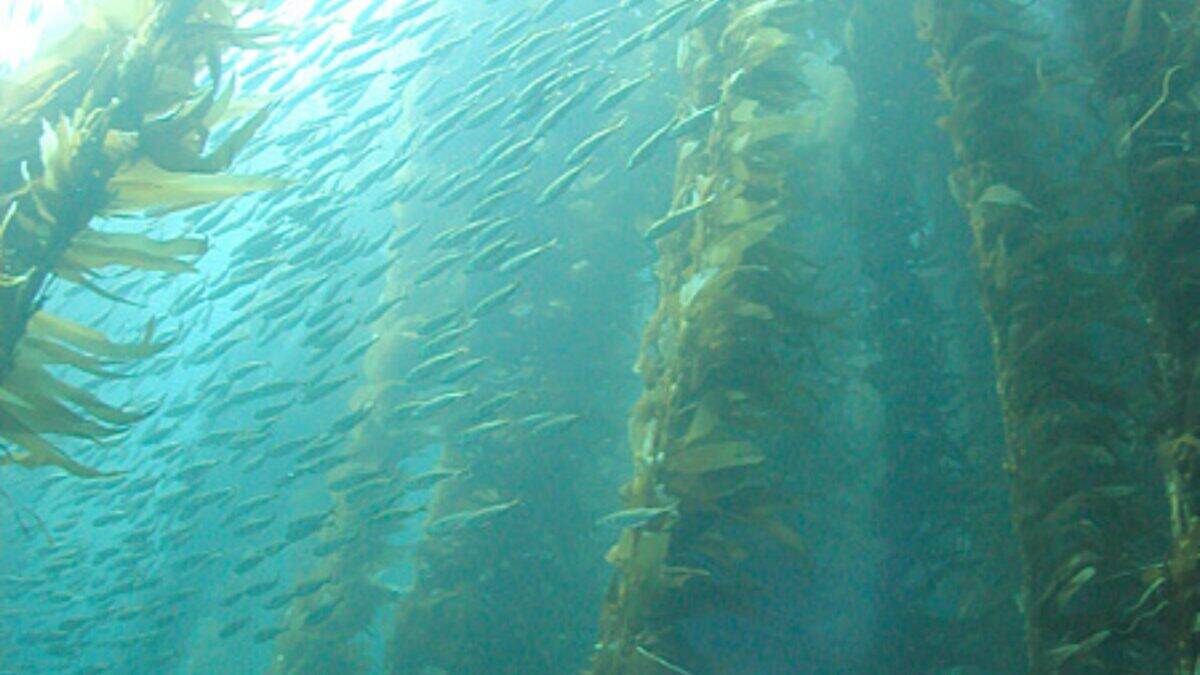

The Vital Importance of Kelp Forests

Kelp forests are among the most productive and dynamic ecosystems on the planet. Giant kelp can grow up to two feet per day under optimal conditions, creating underwater canopies that reach heights of 150 feet. These marine forests serve as the foundation for incredibly biodiverse communities, providing habitat, nursery areas, and feeding grounds for thousands of species including fish, invertebrates, marine mammals, and seabirds. Beyond their ecological value, kelp forests deliver critical ecosystem services to humans. They act as natural buffers against coastal erosion by dampening wave energy, sequester substantial amounts of carbon from the atmosphere, produce oxygen through photosynthesis, and support valuable commercial and recreational fisheries worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually. Scientists have also identified numerous beneficial compounds in kelp with applications in medicine, food production, and other industries. Despite their importance, these underwater forests face mounting threats from climate change, coastal pollution, and ecological imbalances—making their protection and restoration increasingly urgent.

The Sea Urchin Explosion

When sea otters disappeared from coastal ecosystems, one creature in particular experienced a population boom with devastating consequences: the sea urchin. These spiny invertebrates are voracious grazers of kelp, particularly purple sea urchins (Strongylocentrotus purpuratus) and red sea urchins (Mesocentrotus franciscanus) along the Pacific coast. Without predation pressure from sea otters, urchin populations can multiply exponentially, creating what scientists call “urchin barrens”—vast underwater areas stripped of kelp and dominated by dense aggregations of hungry urchins. In some regions, urchin densities have reached staggering levels of more than 70 individuals per square meter. Once established, these barrens create a reinforcing cycle, as the urchins consume not only adult kelp but also newly settling kelp spores, preventing forest regeneration. The transformation from lush kelp forest to barren seafloor can happen with alarming speed—sometimes in just a few years—and can persist for decades in the absence of natural predators. The resulting habitat is dramatically simplified, supporting only a fraction of the biodiversity found in healthy kelp ecosystems and eliminating the many services these forests provide.

Sea Otters: The Kelp Forest Guardians

Sea otters (Enhydra lutris) are perfectly equipped to control sea urchin populations in ways no other predator can match. An adult sea otter consumes 25-30% of its body weight daily—that’s about 9-11 pounds of food per day—with sea urchins often making up a significant portion of their diet. Their remarkable dexterity allows them to handle and crack open urchins with precision, and they’ve even been observed selectively hunting larger, more reproductive urchins, maximizing their impact on urchin population dynamics. Unlike other predators that might visit kelp forests occasionally, sea otters are resident specialists, maintaining constant pressure on urchin populations. Research in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands showed that areas with healthy sea otter populations maintained urchin densities around 2 per square meter, while areas without otters saw densities exceeding 20 per square meter. This predation doesn’t necessarily eliminate sea urchins but transforms their behavior—in the presence of sea otters, surviving urchins often retreat to crevices and feed primarily on kelp detritus rather than grazing actively on living kelp tissues. This behavioral shift creates space for kelp to thrive and rebuild forest structures.

The Trophic Cascade Effect

The relationship between sea otters, sea urchins, and kelp represents a classic trophic cascade—one of the most well-documented examples in marine ecology. A trophic cascade occurs when changes in the abundance of a top predator ripple down through food webs, indirectly affecting organisms two or more feeding levels below. When sea otters return to an ecosystem, they reduce urchin populations, which decreases grazing pressure on kelp, allowing forests to recover and expand. This cascade doesn’t stop with kelp; the restored forests provide habitat complexity that benefits numerous other species. Studies in Alaska have documented 2-5 times more fish species in areas with sea otters versus areas without. The effects extend even beyond the marine environment—healthier kelp forests capture more carbon dioxide, produce more oxygen, and provide more protection for coastlines from storm damage. The sea otter-driven trophic cascade was first scientifically described by James Estes and colleagues in the 1970s, work that revolutionized understanding of predator roles in structuring ecosystems. This research helped shift ecological thinking from a bottom-up perspective (where primary producers control ecosystem dynamics) to recognize the equally crucial top-down forces exerted by predators.

Success Stories: Monterey Bay

Monterey Bay, California presents one of the most compelling case studies of sea otter-driven kelp forest recovery. Following their rediscovery in 1938, California’s remnant sea otter population began a slow expansion from their refuge near Big Sur. As otters recolonized Monterey Bay in the 1960s and 1970s, researchers documented a remarkable transformation. Areas previously dominated by urchin barrens saw rapid kelp regrowth within just 1-2 years of sea otter arrival. By the 1980s, robust kelp forests had been reestablished throughout much of the bay, increasing primary productivity by an estimated 2-4 times compared to urchin-dominated areas. The revitalized ecosystem supported a renaissance of marine life, including commercially valuable fish species like lingcod and rockfish. Today, Monterey Bay’s kelp forests support a thriving ecotourism industry worth over $100 million annually to the local economy. The recovery hasn’t been without challenges—the California sea otter population, now approximately 3,000 individuals, still faces threats from disease, pollution, and habitat degradation. However, the Monterey Bay success story demonstrates how protection of a keystone predator can trigger natural restoration of an entire ecosystem, creating cascading benefits for biodiversity and human communities alike.

The British Columbia Reintroduction Program

Another remarkable chapter in the sea otter conservation story comes from British Columbia, Canada, where a deliberate reintroduction program has yielded dramatic results. Between 1969 and 1972, wildlife managers transplanted 89 sea otters from Alaska to the west coast of Vancouver Island. From this modest beginning, the population has grown to over 8,000 individuals today, reoccupying approximately 25-33% of their historic range in British Columbia. Studies by researchers at the University of British Columbia have documented the profound ecosystem changes following this recolonization. In areas where sea otters have been established for more than 20 years, kelp forest canopy cover has increased by 7-20 times compared to adjacent areas without otters. The biodiversity benefits have been equally impressive—researchers have recorded increases of 37% in species richness after sea otter recovery. The program hasn’t been without controversy, as the return of sea otters has impacted shellfish harvests by First Nations and commercial fisheries. However, longer-term economic analyses suggest that the enhanced productivity of kelp forest ecosystems, including increased finfish populations and ecotourism opportunities, may ultimately generate greater economic value than shellfish harvests alone. The British Columbia case demonstrates both the ecological power of recovery efforts and the importance of addressing human communities’ needs in conservation planning.

Climate Change Resilience and Kelp Forests

As climate change intensifies, kelp forests face mounting threats from marine heatwaves, ocean acidification, and changing current patterns. However, emerging research suggests that sea otter-protected kelp forests may demonstrate greater resilience to these stressors. During the devastating 2014-2016 marine heatwave known as “The Blob” that affected the northeastern Pacific, areas with established sea otter populations maintained significantly more kelp cover than regions without otters. In some sea otter-protected areas, kelp forests retained 40-60% of their pre-heatwave biomass, while unprotected areas saw declines of 80-100%. Scientists attribute this resilience to several mechanisms: predation by sea otters keeps urchin populations below thresholds where they can completely devastate weakened kelp; healthier, more extensive kelp creates localized cooling and pH buffering effects; and more diverse kelp forest communities include species with varying temperature tolerances. Additionally, kelp forests themselves play a role in climate mitigation by sequestering carbon—estimates suggest that a hectare of healthy kelp forest can sequester as much carbon as 10-20 hectares of temperate forest on land. As marine ecosystems face increasing climate impacts, the protective role of sea otters may become even more crucial for maintaining these carbon-capturing underwater forests.

Challenges to Sea Otter Recovery

Despite their ecological importance, sea otter populations still face significant obstacles to full recovery. Current global population estimates stand at approximately 125,000 individuals—still well below historical numbers. In California, population growth has stalled in recent decades, with range expansion limited by several factors. Shark predation, particularly by great white sharks, has increased at the northern and southern edges of the sea otters’ California range, creating what researchers call “mortality hotspots” that impede colonization of new areas. Disease threats also loom large—sea otters are vulnerable to parasites like Toxoplasma gondii (spread through cat feces washing into the ocean) and bacterial infections that can cause periodic die-offs. Human activities pose additional risks, including oil spills (sea otters are particularly vulnerable due to their reliance on fur for insulation), fishing gear entanglement, boat strikes, and exposure to pollutants that can compromise immune function. Climate change adds yet another layer of stress through altered prey availability and habitat conditions. Perhaps most challenging are conflicts with human fisheries—as recovering sea otter populations impact valuable shellfish harvests, some stakeholders resist expansion efforts, creating complex management dilemmas that require balancing ecological benefits against economic concerns.

Innovative Management and Coexistence Strategies

As recognition of sea otters’ ecological role grows, innovative approaches are emerging to facilitate their recovery while addressing human concerns. In southeast Alaska, managers are exploring spatial zoning that designates some areas for sea otter recovery and others for priority shellfish harvesting. In California, a “no-otter zone” policy that attempted to exclude otters from southern waters was officially abandoned in 2012 after proving both biologically ineffective and legally problematic. Conservation organizations are working with shellfish farmers to design and implement otter-resistant gear that protects valuable harvests while allowing coexistence. Some communities are discovering economic benefits from sea otter presence through wildlife tourism—in places like Elkhorn Slough, California, otter-watching generates millions in annual revenue. Indigenous communities along the Pacific coast are incorporating traditional ecological knowledge into management plans, drawing on centuries of coexistence with sea otters prior to the fur trade. The Elakha Alliance in Oregon is building broad stakeholder support for eventual sea otter reintroduction to that state’s waters through extensive community engagement and scientific assessment. These varied approaches recognize that successful conservation requires addressing both ecological and human dimensions of recovery, finding solutions that honor the needs of multiple stakeholders while restoring ecological function.

The Future of Kelp Forest Conservation

Looking ahead, the future of kelp forest ecosystems will likely depend on integrated approaches that combine sea otter recovery with complementary conservation strategies. In areas where sea otter reintroduction is not immediately feasible, direct management of urchin populations through commercial harvesting and targeted removal programs is showing promise. In northern California, a partnership between scientists, commercial divers, and seafood processors has removed millions of purple urchins from strategic locations, creating “urchin-free zones” where kelp can reestablish. Kelp cultivation and restoration techniques are also advancing rapidly, with projects in multiple countries developing methods to seed and grow kelp in degraded areas. Marine protected areas that limit fishing pressure and reduce other stressors provide important refuges where kelp forests can rebuild resilience. Pollution reduction efforts, particularly addressing land-based runoff that can harm kelp reproduction, represent another crucial intervention. However, research consistently shows that where feasible, sea otter recovery remains the most sustainable and effective long-term strategy for kelp forest restoration. The natural predator-prey relationship between otters and urchins evolved over millennia and requires no ongoing human intervention once established. The most successful approaches will likely involve strategic combination of these tools, tailored to the specific ecological, social, and economic context of each region.

The story of sea otters and kelp forests offers a powerful illustration of how restoring a single species can transform entire ecosystems. From the brink of extinction, sea otter recovery has triggered the rebirth of vital kelp forest habitats, creating cascading benefits for thousands of marine species and the human communities that depend on healthy oceans. As climate change and other anthropogenic pressures intensify, the protective role of sea otters becomes increasingly valuable, enhancing the resilience of coastal ecosystems to warming waters and extreme events. The challenges of balancing ecological restoration with human needs remain complex, requiring creative solutions that honor multiple values and stakeholder interests. Yet the remarkable success stories from Monterey Bay, British Columbia, and other regions demonstrate that coexistence is possible and that the ecological dividends of recovery can ultimately benefit both nature and people. As we work to build more sustainable relationships with marine ecosystems, the sea otter’s role as guardian of the kelp forests reminds us of nature’s capacity for healing when keystone species are allowed to fulfill their ecological functions.

- How to Survive a Snake Encounter in the Wild - August 13, 2025

- 10 National Parks with the Most Unpredictable Weather - August 13, 2025

- The Bison of Yellowstone Almost Went Extinct, But Now They’re Roaming Free Again - August 13, 2025