In the animal kingdom, parenting arrangements vary dramatically across species. While maternal care is often considered the norm in many animals, there are fascinating exceptions where fathers take the lead or even exclusive role in raising offspring. These dedicated dads challenge our assumptions about gender roles in nature and demonstrate remarkable parental investment. From seahorses that become pregnant to birds that build nests and incubate eggs, paternal care manifests in diverse and sometimes surprising ways. This article explores various species where fathers shoulder significant or primary parenting responsibilities, highlighting the evolutionary advantages and unique behaviors associated with male-dominated care systems.

The Evolutionary Puzzle of Paternal Care

From an evolutionary perspective, paternal care presents an interesting puzzle. The theory of parental investment suggests that the sex with higher initial reproductive investment (typically females, who produce energy-intensive eggs) should provide more parental care. Yet approximately 10% of fish species, 9% of amphibian species, and numerous bird species feature significant paternal care. Evolutionary biologists suggest that paternal care evolves under specific conditions, including certainty of paternity, limited mating opportunities for males, or environments where biparental or paternal care significantly increases offspring survival. When these conditions align, natural selection may favor devoted dads over competing males. In some cases, male parenting evolved from biparental care systems when female care was gradually reduced, while in others, it appears to have evolved directly from no parental care at all.

Seahorses and Sea Dragons: Male Pregnancy

Perhaps the most extreme example of paternal care occurs in seahorses, sea dragons, and pipefish (family Syngnathidae). In these species, males become literally “pregnant” in an extraordinary role reversal. After an elaborate courtship dance, female seahorses deposit their eggs into the male’s specialized brood pouch. The male then fertilizes the eggs internally, and his pouch provides oxygen, regulates salinity, and supplies nutrients to the developing embryos. After a pregnancy lasting between 10 days and 6 weeks, depending on the species, the male experiences contractions and actively gives birth to fully-formed juvenile seahorses—sometimes up to 2,000 at once. Throughout pregnancy, the father’s body undergoes hormonal changes similar to pregnant females in other species, including increased prolactin levels. This unique reproductive strategy ensures 100% paternity certainty for the investing father and allows females to prepare new eggs immediately, potentially increasing the species’ reproductive efficiency.

Daddy Daycare: The Devoted Emperor Penguin

Emperor penguins (Aptenodytes forsteri) demonstrate extraordinary paternal dedication in one of Earth’s harshest environments. After the female lays a single egg in the Antarctic winter, she transfers it to her mate’s feet, where a special brood pouch keeps it warm. The female then journeys up to 50 miles to the ocean to feed, leaving the father solely responsible for incubating the egg for about two months. During this period, the males endure temperatures as low as -40°F and fierce blizzards while fasting completely—ultimately losing up to 45% of their body weight. To conserve warmth, they form tight huddles, constantly rotating positions so no individual remains too long at the windward edge. The males carefully balance the eggs on their feet throughout this period, as allowing an egg to touch the ice would mean almost certain death for the embryo. When the females return around hatching time, they regurgitate food for the chicks while the severely malnourished fathers finally journey to the sea to feed. This extraordinary division of labor evolved to match the timing of the brief Antarctic summer, when food becomes plentiful just as chicks begin growing rapidly.

Poison Dart Frogs: Piggyback Dads

Among amphibians, several poison dart frog species demonstrate remarkable paternal care. In species like the strawberry poison dart frog (Oophaga pumilio) and the mimic poison frog (Ranitomeya imitator), after females lay eggs on the forest floor, the males take charge of guarding them from predators and keeping them moist by urinating on them or transporting water in specialized skin pockets. Once the eggs hatch into tadpoles, the devoted dad carries the wriggling offspring on his back, one by one, to small water bodies formed in plant cavities high in the rainforest canopy. In some species, the father’s duty ends here, while in others, he continues visiting each tadpole regularly until they metamorphose into froglets. The reproductive strategy of these tiny frogs demonstrates how paternal care can evolve in species where males can effectively guard or transport offspring while females recover and prepare to produce more eggs, maximizing reproductive output in these tiny territorial animals with complex social behaviors.

Rheas and Cassowaries: Large Flightless Bird Fathers

Among the large flightless birds, rheas and cassowaries display remarkable paternal dedication. The greater rhea (Rhea americana) of South America features a breeding system where a dominant male maintains a harem of females who all lay eggs in a single ground nest. After laying, the females depart to potentially mate with other males, while the original male incubates all eggs—often 20-60 from multiple females—and raises the chicks alone for up to six months. Male cassowaries (Casuarius spp.) of Australia and New Guinea similarly take complete responsibility for incubating eggs and raising chicks after females move on to mate with other males. These intimidating birds, standing up to 6.5 feet tall and equipped with dagger-like claws, become surprisingly gentle parents—guiding chicks to feeding grounds, protecting them from predators, and even “babysitting” by sitting quietly while young birds explore nearby vegetation. These parenting arrangements allow females to maximize reproductive output by producing multiple clutches with different males while ensuring offspring receive adequate parental investment.

Jacanas: The “Polyandrous” Wading Birds

Jacanas, sometimes called “lily-trotters” for their ability to walk on floating vegetation, represent one of the clearest examples of sex-role reversal in birds. In species like the northern jacana (Jacana spinosa) and bronze-winged jacana (Metopidius indicus), females are larger and more aggressive than males, and they defend territories containing multiple male partners—a mating system known as polyandry. After mating, each male constructs a floating nest and takes complete responsibility for incubating the eggs and raising the chicks with no female assistance. Remarkably, if a female’s territory is threatened by another female, she may abandon her current clutches of eggs (being incubated by her males) to establish a new territory and mate with new males. This system evolved in environments where food resources for females are unpredictable and where nests face high predation rates, making it advantageous for females to spread reproductive investment across multiple clutches with different males. The males, meanwhile, gain reproductive opportunities they might not otherwise have in a more traditional mating system.

Marsupial Frogs: Pocket-Carrying Papas

In several species of marsupial frogs (genus Gastrotheca) native to Central and South America, males exhibit extraordinary paternal care by carrying developing eggs in specialized pouches on their backs or in their vocal sacs. After external fertilization, the male uses his hind legs to push the eggs into his dorsal pouch, where they remain protected from predators and desiccation. Depending on the species, the eggs may develop entirely within the pouch until tiny froglets emerge, or the male might release tadpoles into water once they reach a certain developmental stage. This remarkable adaptation allows these frogs to reproduce away from standing water, reducing predation risk to eggs and tadpoles. In some species, the pouch provides nutrients and oxygen to the developing embryos, creating a connection somewhat similar to a mammalian placenta. This paternal care system represents a fascinating example of convergent evolution with marsupial mammals, despite evolving through completely independent evolutionary pathways.

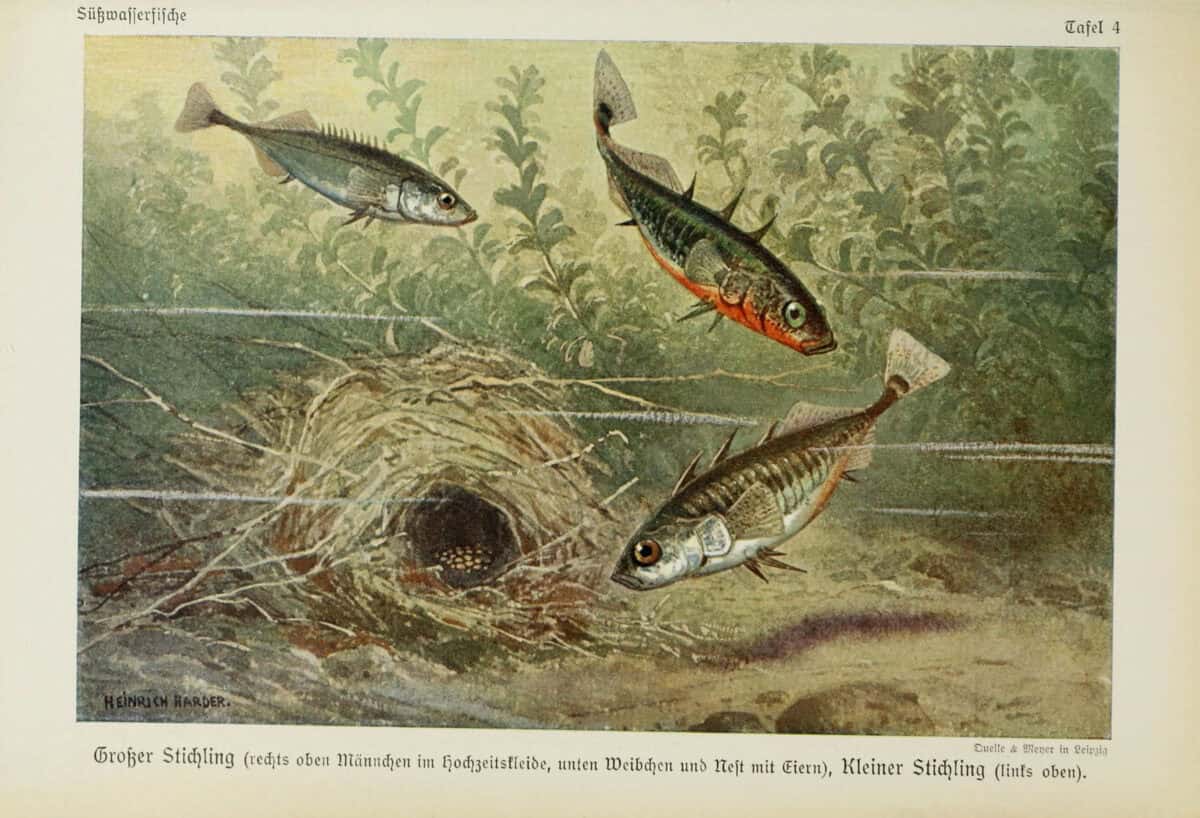

Three-Spined Sticklebacks: Nest-Building Fish Fathers

The three-spined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) has become a model organism for studying paternal care in fish. During breeding season, male sticklebacks develop bright red bellies and blue eyes to attract females while establishing and fiercely defending territories. Each male constructs an elaborate nest by digging a depression in the substrate and gluing together plant material with kidney secretions. When a receptive female approaches, the male performs a zigzag dance and leads her to the nest. After she deposits eggs inside, the male immediately fertilizes them and chases the female away. A successful male may entice several females to lay eggs in his nest, after which he assumes all parenting duties—guarding the eggs from predators, fanning them with his fins to provide oxygen, and removing any eggs that develop fungal infections. Once the eggs hatch, the father continues protecting the fry (baby fish) for about two weeks until they can survive independently. This system evolved partly because males can care for multiple clutches simultaneously and because their bright breeding colors would make them obvious targets for predators while swimming in open water anyway.

Giant Water Bugs: Eggs on Dad’s Back

Giant water bugs (family Belostomatidae) exhibit one of the most visually striking examples of paternal care among insects. In many species, after mating, the female literally glues her eggs onto the male’s back. The male then carries this egg load—sometimes covering his entire dorsal surface—for 1-3 weeks until they hatch. During this time, he performs “brood pumping” behaviors, arching his back and creating water circulation to provide oxygen to the developing eggs while preventing fungal growth. He also carefully positions himself to expose the eggs to optimal temperatures at different times of day. If the eggs become too dry, he’ll submerge himself in water; if they’re threatened by aquatic fungi, he’ll surface and expose them to air. This intimate paternal care significantly increases hatching success compared to eggs laid on submerged vegetation. The system likely evolved because egg-bearing males can continue feeding and moving normally while protecting their offspring, whereas an egg-laden female would experience reduced mobility and increased predation risk.

Sandpipers: Role-Reversal in Shorebirds

Several shorebird species in the sandpiper family demonstrate fascinating examples of sex-role reversal and extensive paternal care. In species like the spotted sandpiper (Actitis macularius), red phalarope (Phalaropus fulicarius), and red-necked phalarope (Phalaropus lobatus), traditional sex roles are flipped—females are larger and more brightly colored than males and compete for mates, while males provide most or all parental care. Female phalaropes court males with elaborate displays, and after mating and egg-laying, they promptly abandon the nest to search for additional mates. Males then assume all incubation duties and care for the precocial chicks after hatching. This system evolved in environments where the breeding season is short and food resources abundant, making it advantageous for females to maximize egg production by mating with multiple males. The phalaropes’ unusual mating system also correlates with their unusual feeding technique—they swim in tight circles to create upwellings that bring small aquatic prey to the surface, a behavior rarely seen in other shorebirds.

Darwin’s Frogs: Vocal Sac Nurseries

Darwin’s frogs (genus Rhinoderma) from Chile and Argentina demonstrate perhaps the most unusual paternal care system among amphibians. In both Darwin’s frog (Rhinoderma darwinii) and Chile Darwin’s frog (Rhinoderma rufum), after external fertilization, the male literally swallows the developing eggs into his vocal sac. Inside this makeshift “womb,” the eggs develop into tadpoles and complete metamorphosis, with the father’s vocal sac expanding dramatically to accommodate the growing offspring. After 6-8 weeks, the father “gives birth” by opening his mouth wide and allowing fully formed froglets to hop out. During the brooding period, the male stops feeding but continues to vocalize despite carrying up to 15 developing offspring in his throat. This remarkable adaptation protects vulnerable eggs and tadpoles from predators and desiccation in their temperate forest habitat. Tragically, Chile Darwin’s frog is now believed to be extinct, and Darwin’s frog is endangered, partly due to chytrid fungus infections. Their unique reproductive strategy, while successful for millions of years, may have made them particularly vulnerable to modern threats.

Midwife Toads: Birth Assistants with a Twist

Midwife toads (genus Alytes) native to Western Europe and North Africa have earned their name through the males’ distinctive parental care strategy. When a female midwife toad is ready to lay eggs, she and her mate engage in a complex mating ritual different from most amphibians. Rather than depositing eggs in water, the female extrudes a string of eggs which the male fertilizes externally. Then comes the remarkable part—the male wraps the string of fertilized eggs around his hind legs and carries them for 3-6 weeks. During this period, he keeps the eggs moist by periodically soaking in dew or shallow water and protects them from predators. When the eggs are ready to hatch, the male enters a suitable water body where tadpoles emerge and begin their aquatic life stage. This paternal care system likely evolved to protect eggs from aquatic predators during early development while allowing reproduction in areas distant from permanent water bodies. The male can continue feeding normally while carrying eggs, whereas a female burdened with eggs might be more vulnerable to predation.

The diverse examples of paternal care across the animal kingdom challenge our assumptions about “natural” parenting roles and reveal the remarkable flexibility of reproductive strategies that have evolved through natural selection. These devoted dads—from pregnant seahorses to nest-guarding sticklebacks and vocal sac-brooding frogs—demonstrate that male parenting can be equally as complex, dedicated, and effective as maternal care when ecological conditions favor such arrangements. Scientists continue to study these systems not only to understand the evolution of parenting behaviors but also because they provide insights into sexual selection, mating systems, and the countless ways organisms have adapted to maximize reproductive success in different environments. As human societies continue to evolve their own understanding of parenting roles and gender expectations, perhaps these natural examples of paternal dedication can inspire appreciation for the diversity of successful family structures found throughout the natural world.

- Wildlife Encounters You Might Have on a Spring Hike - August 23, 2025

- Wildlife That Thrives in the Carolinas Year-Round - August 23, 2025

- The Role of Bears in Keeping Forests Healthy - August 23, 2025