In the dense forests of South America, a remarkable scene unfolds regularly: capuchin monkeys carefully selecting stones and bringing them to anvil-like surfaces to crack open tough palm nuts. This sophisticated behavior represents one of the most impressive examples of tool use in non-human primates. Capuchin monkeys, particularly the bearded capuchin (Sapajus libidinosus), have developed a complex process of nut-cracking that requires planning, precision, and an understanding of cause and effect. Their ability to use stone tools challenges our understanding of animal cognition and provides fascinating insights into the evolution of intelligence. As we explore this remarkable behavior, we’ll discover how these small primates demonstrate problem-solving abilities that were once thought to be uniquely human or limited to great apes.

The Capuchin’s Natural Toolkit

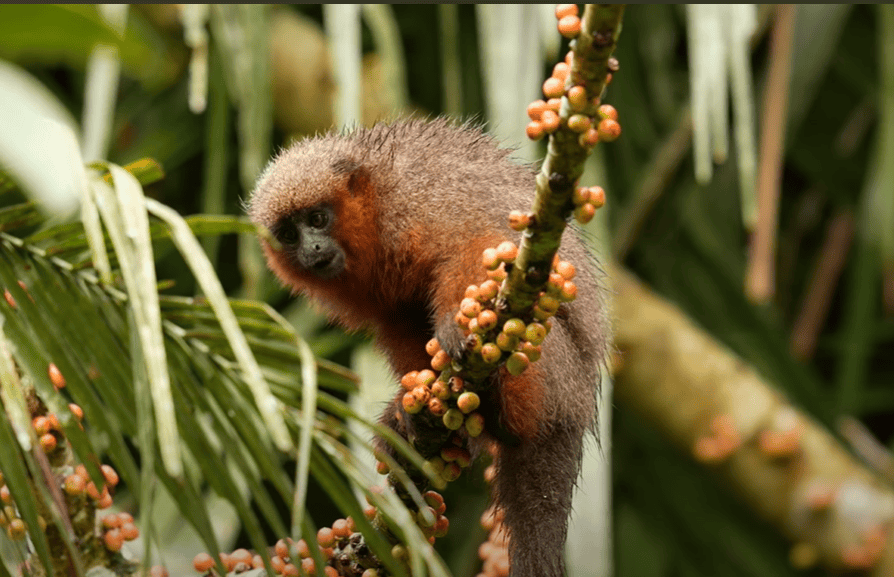

Capuchin monkeys are naturally equipped with impressive physical and cognitive abilities that predispose them to tool use. Their dexterous hands feature partially opposable thumbs that allow for precision gripping—a crucial prerequisite for manipulating tools effectively. Complementing their physical capabilities is their remarkable intelligence; capuchins possess among the largest brain-to-body size ratios of any monkey species, suggesting significant cognitive potential. These monkeys are also innately curious and persistent, characteristics that drive them to explore and interact with objects in their environment. While their natural diet includes fruits, insects, and small vertebrates, the addition of hard-shelled palm nuts presents a challenge that their teeth alone cannot overcome. This nutritional incentive, combined with their physical capabilities and intelligence, creates the perfect conditions for the development of tool use as a solution to accessing these valuable, energy-rich foods.

The Discovery of Nut-Cracking Behavior

The scientific documentation of capuchin nut-cracking behavior came relatively late compared to observations of tool use in chimpanzees. In 2004, researchers led by Dr. Eduardo Ottoni and Dr. Patricia Izar first published comprehensive findings about wild bearded capuchins in northeastern Brazil using stone tools to crack open palm nuts. This discovery was particularly significant because previously, such sophisticated tool use was primarily associated with great apes, not monkeys. The research site in Serra da Capivara National Park became ground zero for studying this behavior, with subsequent research also documenting similar behaviors in other capuchin populations in different regions of Brazil. These discoveries challenged previous assumptions about the cognitive capabilities of monkeys and highlighted convergent evolution of tool use across primate lineages. The findings sparked a new wave of research into capuchin cognition and the environmental factors that might promote the development of such complex behaviors.

The Nuts That Drive Innovation

The palm nuts that capuchins target are remarkable for their nutritional value and the challenge they present. Species like the tucum (Astrocaryum campestre) and piassava (Orbignya spp.) produce nuts with extremely hard shells that protect the nutritious kernel inside. These nuts contain high levels of proteins and fats—essential nutrients that are otherwise difficult for the monkeys to obtain in their environment. Chemical analysis of these nuts reveals they can contain up to 70% fat and 13% protein, making them calorically dense energy packages. The mechanical resistance of these nuts is impressive, with some requiring forces exceeding 300 pounds per square inch to crack—far beyond what capuchin jaws and teeth can generate directly. This combination of high nutritional reward and difficult access creates strong selective pressure for innovative solutions, driving the evolution of tool use. The seasonal availability of these nuts also affects the frequency of tool use, with capuchins relying more heavily on this technique during periods when other food sources are scarce.

The Sophisticated Nut-Cracking Process

The process by which capuchins crack nuts involves multiple steps and decisions, showcasing their cognitive sophistication. First, a monkey must locate and select an appropriate hammer stone—typically granite or quartzite rocks weighing between 0.5 and 1 kilogram. They often transport these tools considerable distances, sometimes carrying them for over 100 meters from their source to nut-cracking sites. Next, they must find a suitable anvil, which can be either another stone with a flat, stable surface or a tree root that provides the necessary stability. The monkey positions the nut precisely in a depression or crevice on the anvil, holds the hammer stone with both hands, and strikes the nut with controlled force. This process often requires multiple strikes, with the monkey adjusting the force and angle with each attempt. Research has shown that capuchins can modulate the force of their strikes based on the hardness of different nut species, demonstrating a nuanced understanding of the physical properties involved. Failed attempts often lead to repositioning of the nut or selection of a different hammer stone, showing problem-solving capabilities and persistence.

Tool Selection and Material Preferences

Capuchin monkeys display remarkable selectivity when choosing their nut-cracking tools, revealing an intuitive understanding of physics that rivals that of young children. Research by Dr. Dorothy Fragaszy and colleagues has demonstrated that these primates prefer stones with specific characteristics: hardness, appropriate weight, and manageable size. Quartzite and granite are favored materials due to their durability and density. Experiments have shown that when presented with stones of different weights, capuchins consistently select those within an optimal range—heavy enough to crack the target nuts efficiently but not so heavy as to be unwieldy. They also prefer stones with relatively flat surfaces that provide stability during striking. Perhaps most impressively, capuchins can assess a stone’s suitability by touch alone, often testing potential tools by briefly lifting them before committing to transport. This discrimination extends to anvils as well, with monkeys preferring those with natural depressions that help stabilize the nuts during striking. These preferences demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of tool properties that develops through experience and possibly observational learning.

Learning and Social Transmission

The acquisition of nut-cracking skills in capuchin communities represents a fascinating case of social learning and cultural transmission. Young capuchins typically spend years developing proficiency in this technique, beginning around age two with playful manipulation of nuts and stones. They learn primarily through close observation of skilled adults, particularly their mothers and other group members. Research has documented young monkeys spending significant time watching nut-cracking events from close proximity, a behavior termed “attentional bias.” Unlike direct teaching, which hasn’t been observed, this form of observational learning allows the techniques to spread through the community. Proficiency typically isn’t achieved until around age six or seven, highlighting the complexity of the skill. Interestingly, different capuchin groups show distinctive nut-cracking styles and tool preferences that persist across generations, suggesting cultural variations akin to traditions. This social transmission creates a form of non-genetic inheritance whereby knowledge accumulates within communities, allowing for the maintenance and refinement of techniques over time without genetic changes—a hallmark of cultural evolution.

Comparing Capuchin and Chimpanzee Tool Use

The parallel evolution of nut-cracking behavior in capuchin monkeys and chimpanzees presents a fascinating case of convergent evolution in cognitive abilities across distantly related primate lineages. These species last shared a common ancestor approximately 35 million years ago, suggesting their tool-using behaviors evolved independently in response to similar ecological challenges. While both species use hammer stones and anvils to access encased foods, there are notable differences in their techniques. Chimpanzees typically use larger, heavier hammers and can crack harder nuts, consistent with their greater physical strength. Capuchins, despite their smaller size, display remarkable efficiency, often using proportionally heavier stones relative to their body weight. In terms of learning, both species acquire the skill gradually through observation, though chimpanzees may show more variations in technique across different populations. Both demonstrate selective tool choice and transport tools to food sources, indicating advanced planning. The independent emergence of these complex behaviors in separate evolutionary lineages suggests that certain ecological pressures—like hard-shelled, nutritious foods—may predictably drive the evolution of sophisticated cognitive abilities across different species.

Ecological Factors Influencing Tool Use

The development of stone tool use in capuchin populations is strongly linked to specific ecological conditions. Research reveals that not all capuchin species or populations engage in nut-cracking, with the behavior primarily documented in savanna-dwelling bearded capuchins (Sapajus libidinosus) rather than their forest-dwelling relatives. This distribution correlates with several key environmental factors. First, the presence of suitable stone materials is essential—regions with natural outcrops of quartzite or granite provide the necessary hammers. Second, the seasonal availability of hard-shelled palm nuts creates nutritional incentives for developing complex extraction techniques. Third, more open habitats with less dense vegetation may facilitate terrestrial movement and the transport of heavy objects. Intriguingly, studies comparing tool-using and non-tool-using populations have found that even when provided with appropriate stones and nuts, capuchins with no prior exposure to nut-cracking rarely develop the behavior spontaneously, suggesting that ecological factors must combine with social transmission for the behavior to become established. This highlights how specific ecological niches can drive cognitive innovations that become incorporated into a species’ behavioral repertoire through cultural evolution.

Archaeological Evidence of Capuchin Tool Use

The study of capuchin tool use has given rise to a fascinating new field: primate archaeology. Researchers have discovered evidence suggesting that capuchin monkeys have been using stone tools for at least 3,000 years, based on excavations at sites in Serra da Capivara National Park in Brazil. These archaeological investigations have unearthed stone tools bearing distinctive damage patterns consistent with nut-cracking activities, along with residues from processed palm nuts. The tools found in deeper, older layers are remarkably similar to those used by contemporary monkeys, indicating a long-standing technological tradition. This evidence constitutes the oldest known record of tool use by non-human primates outside Africa. By applying traditional archaeological methods to non-human primate behavior, researchers can track changes in tool selection and usage over time, providing insights into the evolution of capuchin cognition. These findings challenge the notion that sophisticated tool use is a recent development and suggest that capuchins have been technological innovators for thousands of years—a striking example of non-human material culture with temporal depth comparable to some human technological traditions.

Cognitive Implications of Tool Use

The sophisticated tool use demonstrated by capuchin monkeys reveals cognitive abilities that extend far beyond simple trial-and-error learning. Their nut-cracking behavior requires a complex understanding of cause and effect relationships, physical properties of objects, and spatial relationships. Cognitive studies have shown that capuchins possess several advanced mental capabilities that support their tool use. They demonstrate means-end reasoning—understanding that using the stone (means) leads to accessing the nut meat (end). They exhibit planning abilities, evidenced by transporting appropriate tools to food sources in anticipation of future needs. Research using experimental paradigms has demonstrated that these monkeys understand the functional properties of potential tools, selecting those with appropriate weight and hardness even when visual cues are controlled for. Perhaps most impressively, capuchins show metacognitive abilities—they appear aware of their own knowledge and limitations, as evidenced by their willingness to invest effort in tool transport only when suitable nuts are available. These cognitive capabilities suggest that sophisticated causal reasoning and physical cognition evolved multiple times in the primate lineage, challenging earlier assumptions about the uniqueness of great ape and human cognition.

Conservation Implications

The remarkable tool-using capabilities of capuchin monkeys highlight their ecological and cognitive significance, underscoring critical conservation concerns. Many capuchin populations face serious threats from habitat destruction, particularly the conversion of their native forests and savannas to agricultural land. This habitat loss is especially problematic for tool-using populations, as it can disrupt access to both the nuts they process and the stone materials they require as tools. Additionally, the fragmentation of habitats can isolate populations, potentially leading to the loss of culturally transmitted behaviors like nut-cracking if key skilled individuals are lost. Conservation efforts focusing on capuchins now increasingly recognize the importance of preserving not just the animals themselves but their entire technological landscapes—including nut-bearing palms and geological features that provide tool materials. Some researchers have proposed that tool-using capuchin populations deserve special conservation status as repositories of unique behavioral traditions. Protecting these remarkable primates requires integrated approaches that preserve biological diversity while also safeguarding cultural diversity within non-human species—a relatively new frontier in conservation biology that acknowledges the importance of learned behaviors in animal societies.

The nut-cracking behavior of capuchin monkeys represents one of the most sophisticated examples of tool use in the animal kingdom, offering profound insights into the evolution of intelligence. By demonstrating that complex tool use evolved independently in multiple primate lineages, capuchins challenge the notion that such advanced cognition is unique to humans and great apes. Their technological prowess suggests that similar ecological pressures—specifically, the presence of nutritionally valuable but physically protected foods—can drive the convergent evolution of sophisticated problem-solving abilities across different evolutionary paths. Furthermore, the cultural transmission of these skills within capuchin communities illustrates how social learning can allow behavioral adaptations to spread without genetic changes, creating a system of knowledge accumulation that parallels certain aspects of human cultural evolution. As we continue to study these remarkable primates, they remind us that intelligence has multiple origins and expressions in the natural world, enriching our understanding of how complex cognition emerges and evolves under the right conditions.

- Capuchins Crack Nuts With Rocks - August 18, 2025

- The Slowest Animal Is Not the Sloth - August 18, 2025

- The Biggest Hailstone Ever Recorded—And How Much It Weighed - August 18, 2025