Deep in the mist-shrouded mountains along the Vietnam-Laos border lives a creature so elusive that scientists didn’t confirm its existence until 1992. The saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis), often called the Asian unicorn, represents one of the most spectacular zoological discoveries of the 20th century. This mystical-looking animal with long, parallel horns isn’t actually related to unicorns or rhinos—it’s a member of the bovid family alongside cattle, sheep, and antelopes. Despite being discovered three decades ago, the saola remains one of the world’s least-known large mammals, living a secret life that science has barely begun to unravel. Its extreme rarity, shy nature, and remote habitat have created an almost mythical status, with fewer scientists having seen a living saola than have summited Mount Everest. This is the extraordinary story of Asia’s hidden unicorn—a conservation icon and living symbol of how much remains to be discovered in our natural world.

The Remarkable Discovery That Shocked Science

The scientific community was stunned in 1992 when researchers from Vietnam’s Ministry of Forestry and the World Wildlife Fund discovered an unusual skull with long, straight horns in a hunter’s home in Vietnam’s Vu Quang Nature Reserve. This wasn’t just a new species, but an entirely new genus of large mammal—something extraordinarily rare in modern zoology. The discovery represented the first new large mammal genus identified since the okapi in 1901. DNA analysis revealed the saola was a primitive member of the bovid family, most closely related to wild cattle but unique enough to warrant its own classification. The scientific name, Pseudoryx nghetinhensis, references its superficial resemblance to the oryx antelopes of Africa and Arabia, while acknowledging its discovery location in Vietnam’s Nghe-Tinh province. The finding was so significant that it sparked increased scientific interest in the Annamite Mountains, leading to discoveries of several other previously unknown large mammals in the region, including the large-antlered muntjac and the Annamite striped rabbit.

Physical Characteristics of Nature’s Phantom

The saola’s appearance is both striking and distinctive. Standing approximately 33 inches (85 cm) at the shoulder and weighing between 176-220 pounds (80-100 kg), the saola has a sleek, bovine body covered in smooth, chocolate-brown to black fur. Its most distinctive feature is the pair of nearly parallel horns that can reach up to 20 inches (50 cm) in length. Unlike antlers, these horns do not branch or shed and are found on both males and females. The saola’s face bears unique white markings, including a white stripe along the muzzle and striking white patches above the eyes that give it an alert, curious expression. Its large, dark eyes and round ears contribute to its gentle appearance. Perhaps most unusual is the large pair of maxillary glands near the snout—the largest of any living mammal—which may play a role in marking territory or attracting mates. The saola’s overall appearance has been compared to a hybrid between an antelope, a goat, and a cattle species, reflecting its evolutionary uniqueness as a living fossil that represents one of the most ancient bovid lineages.

The Mysterious Habitat of the Annamite Range

The saola’s kingdom is confined to the dense, tropical forests of the Annamite Mountain Range, which forms the border between Vietnam and Laos. This ancient mountain chain creates a unique ecosystem characterized by steep slopes, dense vegetation, and high rainfall. The saola appears to prefer elevations between 1,000-4,000 feet (300-1,200 meters), inhabiting areas with closed-canopy forests and proximity to streams or rivers. The region experiences distinct wet and dry seasons, with annual rainfall exceeding 78 inches (2,000 mm) in many areas. This lush environment creates the perfect setting for an animal that thrives on seclusion, with thick understory vegetation providing both food and cover. The Annamite Mountains represent a biodiversity hotspot, home to numerous endemic species that evolved in isolation. The region’s remoteness and difficult terrain have historically limited human access, helping protect the saola and other wildlife. However, this same inaccessibility has significantly hampered scientific study of the species in its natural habitat. Researchers believe the saola may migrate seasonally within this range, moving to higher elevations during the wet season and descending during drier periods, though direct observations of these movements remain exceedingly rare.

Behavioral Patterns and Daily Life

The secretive nature of the saola means that most of our understanding of its behavior comes from limited camera trap footage, a few brief captive specimens, and accounts from local villagers. The saola appears to be primarily diurnal, active during daylight hours when it forages for food. They are generally solitary or found in pairs, though small groups of up to seven individuals have occasionally been reported. Unlike many bovids that form large herds, the saola seems to prefer a quiet, secluded existence. They are believed to be territorial, with males using their maxillary gland secretions to mark vegetation within their range. Camera trap evidence suggests they follow regular paths through the forest, often along streams or ridgelines. The saola’s movement is described as graceful and deliberate—they walk with a distinctive lateral gait similar to other forest bovids, allowing them to navigate dense vegetation silently. They demonstrate remarkable agility on steep terrain despite their relatively stocky build. When startled, observers report that saola typically freeze rather than flee immediately, perhaps an evolutionary adaptation to avoid detection by predators like dholes and tigers in their dense forest habitat. This tendency to remain motionless when threatened may unfortunately make them particularly vulnerable to human hunters and their snares.

Dietary Preferences of a Forest Gourmet

The saola’s diet reflects its specialized forest habitat, consisting primarily of the leaves, shoots, and stems of riverside plants and small shrubs. Unlike many bovids that are primarily grazers, the saola is a browser, using its flexible tongue to pluck specific leaves and shoots. Analysis of feeding sites suggests they are selective eaters, preferring approximately 40 known plant species from the figwort and nettle families. Their narrow, pointed muzzle allows them to select specific plant parts, avoiding those with high toxicity or low nutritional value. Field observations indicate that saola spend up to 10 hours daily foraging, taking frequent breaks to rest and ruminate. Like other bovids, they are ruminants with a four-chambered stomach that allows them to extract maximum nutrition from fibrous plant material through fermentation and secondary chewing. Saola appear particularly attracted to plants growing along streams and riverbanks, which may explain their preference for habitat near water sources. During the dry season, they likely rely more heavily on fallen fruits and become more dependent on the moisture content of their food plants. This specialized diet may represent another challenge to their survival, as habitat degradation affects the availability of their preferred food plants.

Reproduction and Life Cycle Mysteries

The reproductive biology of the saola remains one of the most significant gaps in our scientific understanding. No saola has ever been born in captivity, and few, if any, pregnant females have been scientifically documented. Based on observations of similar-sized bovids and limited local reports, researchers believe saola have a gestation period of approximately 8-9 months, likely giving birth to a single calf. Local villagers report occasional sightings of females with young calves during the November to February period, suggesting a breeding season that coincides with the end of the wet season. Both sexes possess horns, though males may have slightly thicker and longer ones. Unlike deer, which shed their antlers annually, saola horns are permanent structures that grow throughout their lifetime. The lifespan of wild saola is unknown, though estimates based on similar-sized bovids suggest a potential lifespan of 8-11 years in optimal conditions. Tragically, attempts to maintain saola in captivity have all ended in failure, with animals surviving only days or weeks before succumbing to stress, improper diet, or disease. This has severely limited opportunities to study their reproductive biology and has complicated conservation breeding efforts that might help preserve the species.

Cultural Significance Among Indigenous Communities

Long before Western science confirmed the saola’s existence, the animal held a place in the cultural knowledge of several indigenous groups living in the Annamite region. The name “saola” itself comes from the Tai language spoken in Vietnam and Laos, roughly translating to “spindle horns” in reference to the weaving tools traditionally used in the region. Among the Van Kieu people of central Vietnam, the saola appears in folk songs and stories as a symbol of the untamed forest and its mysteries. Traditional hunters recognized the animal as distinct from more common forest ungulates and considered encountering one to be a sign of exceptional luck. Some communities believed that the saola possessed spiritual qualities, with its horns occasionally used in traditional medicine or as ceremonial objects. Notably, many tribal groups had taboos against hunting saola, believing that harm would come to those who killed this peaceful forest dweller. These cultural connections highlight the deep relationship between indigenous knowledge and biodiversity, as local communities recognized the species’ uniqueness long before formal scientific discovery. Today, conservation organizations work closely with these communities, drawing on their traditional ecological knowledge to help locate and protect remaining saola populations while respecting cultural traditions and supporting sustainable livelihoods.

The Perilous Conservation Status

The saola faces an extinction crisis of extraordinary proportions. Classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, it is considered one of the most endangered large mammals on Earth. Current population estimates suggest fewer than 100 individuals may remain in the wild, possibly as few as 25. No saola exists in captivity, meaning the loss of wild populations would represent the complete extinction of the species. The primary threat comes from intensive wire-snare poaching throughout their range. Though saola are rarely targeted specifically, they fall victim to indiscriminate snaring aimed at more common species like deer and wild pigs whose meat and body parts supply the thriving wildlife trade in Southeast Asia. Additionally, their habitat faces relentless pressure from logging, agricultural expansion, and infrastructure development like roads and hydroelectric projects that fragment their forest home. The species’ naturally low population density and limited geographic range make them particularly vulnerable to these threats. Their reproductive rate appears slow, with females likely producing only one calf every 1-2 years, making population recovery extremely challenging even under ideal conditions. Climate change represents an emerging threat, as rising temperatures and changing precipitation patterns may affect the specialized mountain forest ecosystems upon which saola depend.

Conservation Efforts and Scientific Challenges

he race to save the saola has united conservation organizations, governments, and local communities in unprecedented collaboration. In 2006, the first Saola Nature Reserves were established in Vietnam, followed by protected areas in Laos. The IUCN Saola Working Group, formed in 2006, coordinates global conservation efforts for the species. Innovative approaches include the removal of thousands of snares from forests through intensive patrolling by local rangers. Conservation groups have established community-based patrol teams that employ former hunters as forest guardians, combining income opportunities with protection efforts. Some projects use environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling of streams to detect saola presence without visual confirmation. Perhaps most ambitious is the Saola Conservation Breeding Center being developed in Vietnam’s Bach Ma National Park—a last-resort effort to capture remaining individuals for a captive breeding program before wild populations disappear completely. However, the scientific challenges remain immense. The saola’s extreme rarity means that basic biological information about reproduction, diet requirements, and health needs remains unknown. No saola has been photographed in the wild by scientists since 2013, despite thousands of camera trap nights. This lack of sightings makes it difficult to locate individuals for conservation breeding efforts or even confirm which areas still harbor populations, forcing conservationists to make critical decisions based on limited data.

The Saola as an Umbrella Species

Conservation biologists increasingly recognize the saola’s importance as an umbrella species—one whose protection benefits numerous other species sharing its habitat. The Annamite Mountains where saola live contain exceptional biodiversity, including several other recently discovered mammals like the Annamite striped rabbit, large-antlered muntjac, and Annamite dark muntjac. By focusing conservation efforts on protecting saola habitat and reducing hunting pressure, these initiatives create a protective umbrella for countless other species. Protected areas established for saola conservation now safeguard over 400,000 hectares of biodiverse forest across Vietnam and Laos. Anti-poaching patrols targeting saola protection have removed more than 130,000 snares from these forests since 2011, benefiting all terrestrial wildlife. The saola’s charismatic appearance and unique story have helped raise international awareness about the broader biodiversity crisis in Southeast Asia, where hunting and habitat loss threaten numerous species. As a flagship species, the saola has attracted funding and attention that might otherwise not have been directed toward this region. Conservation groups have leveraged the saola’s appeal to implement community-based conservation programs that benefit both wildlife and local people through alternative livelihood development, improved agricultural practices, and payments for ecosystem services that maintain forest integrity.

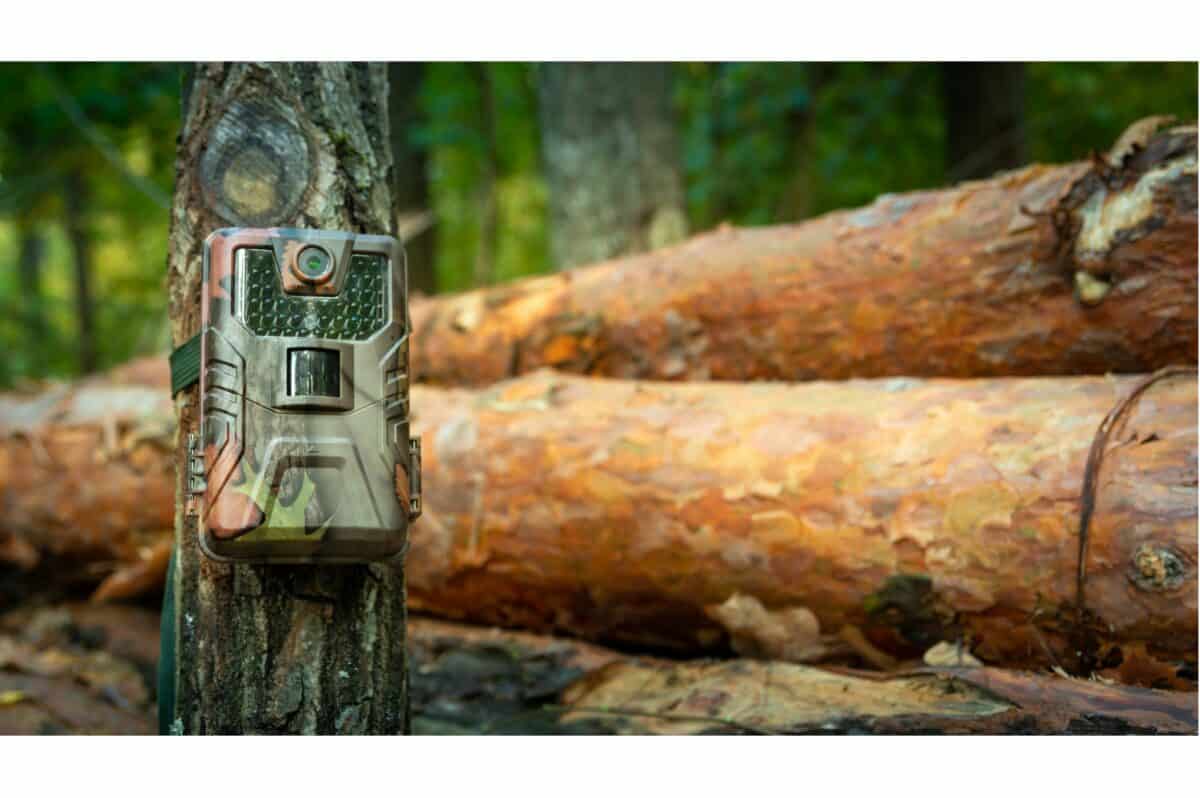

Scientific Detection Methods and Technologies

The extreme rarity of the saola has forced scientists to develop innovative methods for detecting this phantom of the forest. Traditional wildlife survey methods like line transects have proven ineffective due to the species’ secretive nature and low population density. Camera trapping remains the most widely used detection method, with sophisticated camera arrays deployed across potential saola habitat. These units, triggered by motion and heat, operate continuously for months in remote locations. To improve efficiency, researchers use occupancy modeling and species distribution models to identify high-probability saola areas for focused camera deployment. Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling represents a cutting-edge approach, analyzing water samples from streams for cellular material shed by saola. This technique can detect minute traces of DNA from skin cells, hair, and bodily fluids that wash into waterways. Researchers also employ local ecological knowledge (LEK) surveys, interviewing indigenous hunters and forest users about saola sightings, signs, and historical presence. Some projects train detection dogs to identify saola scent from dung or hair samples, while others use passive acoustic monitoring to record potential saola vocalizations. Remote sensing technologies, including satellite imagery and LiDAR, help identify and monitor suitable habitat areas. Most recently, conservation organizations have established a genetic reference database from historical specimens, enabling positive identification of any biological samples potentially collected from wild saola in the future.

Comparison with Other Mysterious Mammals

The saola belongs to an exclusive club of large mammals discovered relatively recently by science. Perhaps its closest parallel is the okapi, discovered in 1901 in the Democratic Republic of Congo—another forest-dwelling ungulate that remained hidden from Western science despite being known to indigenous peoples. Like the saola, the okapi faced initial skepticism from scientists who doubted reports of its existence. The giant muntjac, discovered in the same region as the saola in 1994, represents another recent large mammal find, though it belongs to a previously known genus. The saola differs from these examples in its extreme rarity—while okapi are successfully bred in zoos worldwide, no saola has survived in captivity. The kouprey, another Southeast Asian bovid discovered in 1937, shares the saola’s critically endangered status and may already be extinct. The saola differs from cryptids like the Loch Ness Monster or Bigfoot in having verified physical evidence and scientific documentation, though its elusiveness has earned it similar “mythical” status in popular accounts. The saola most closely resembles the story of the mountain gorilla, which was considered mythical by Western science until 1902 despite indigenous knowledge of its existence. Unlike the mountain gorilla, which recovered from fewer than 250 individuals to over 1,000 today through intensive conservation, the saola’s future remains precariously uncertain despite similar protection efforts.

The saola stands at a crucial crossroads, embodying both the wonder of unexpected discovery and the tragedy of potential extinction within our lifetime. Its story reminds us that our planet still harbors remarkable secrets, even as human activities threaten to eliminate them before they’re fully understood. Without dramatic intervention, this living fossil—a unique evolutionary branch that survived for millions of years—could disappear within a decade, representing an irreplaceable loss to earth’s biodiversity. Yet hope remains in the dedicated efforts of conservationists, scientists, governments, and local communities united in their determination to prevent the saola’s extinction. The ultimate fate of the Asian unicorn will serve as a powerful indicator of humanity’s commitment to preserving the planet’s most vulnerable and mysterious creatures. As

- The Most Bizarre Animal Migration You’ve Never Heard Of - August 20, 2025

- Fierce Animal Moms Who Would Do Anything for Their Babies - August 20, 2025

- The Secret Life of the Saola: Asia’s Hidden “Unicorn” - August 20, 2025