Throughout history, certain animals have played pivotal roles in scientific discovery, becoming the unsung heroes of research that transformed human understanding of the world. From the smallest fruit flies to the most complex primates, these creatures have contributed to breakthroughs in medicine, genetics, space exploration, psychology, and countless other fields. Their sacrifices and unique characteristics have paved the way for vaccines, life-saving surgical techniques, evolutionary theories, and even our understanding of human behavior. This article explores 18 remarkable animals whose contributions to science have forever changed our world, highlighting their stories and the lasting impact of their scientific legacy.

13. Dolly the Sheep The Cloning Revolution

Born on July 5, 1996, at the Roslin Institute in Scotland, Dolly the sheep became the first mammal successfully cloned from an adult cell, revolutionizing our understanding of developmental biology. Scientists created her using a technique called somatic cell nuclear transfer, where they removed the nucleus from an adult sheep’s mammary gland cell and transferred it into an egg cell whose nucleus had been removed. This groundbreaking achievement demonstrated that specialized adult cells could be reprogrammed to create an entire organism, challenging the prevailing scientific belief that once cells differentiated, their genetic potential became permanently restricted. Although Dolly lived only six years—about half the normal sheep lifespan—before succumbing to lung disease and arthritis, her existence opened new possibilities for regenerative medicine, conservation of endangered species, and sparked important ethical debates about human cloning. Today, her preserved body stands in Edinburgh’s National Museum of Scotland, a testament to one of the most significant scientific breakthroughs of the 20th century.

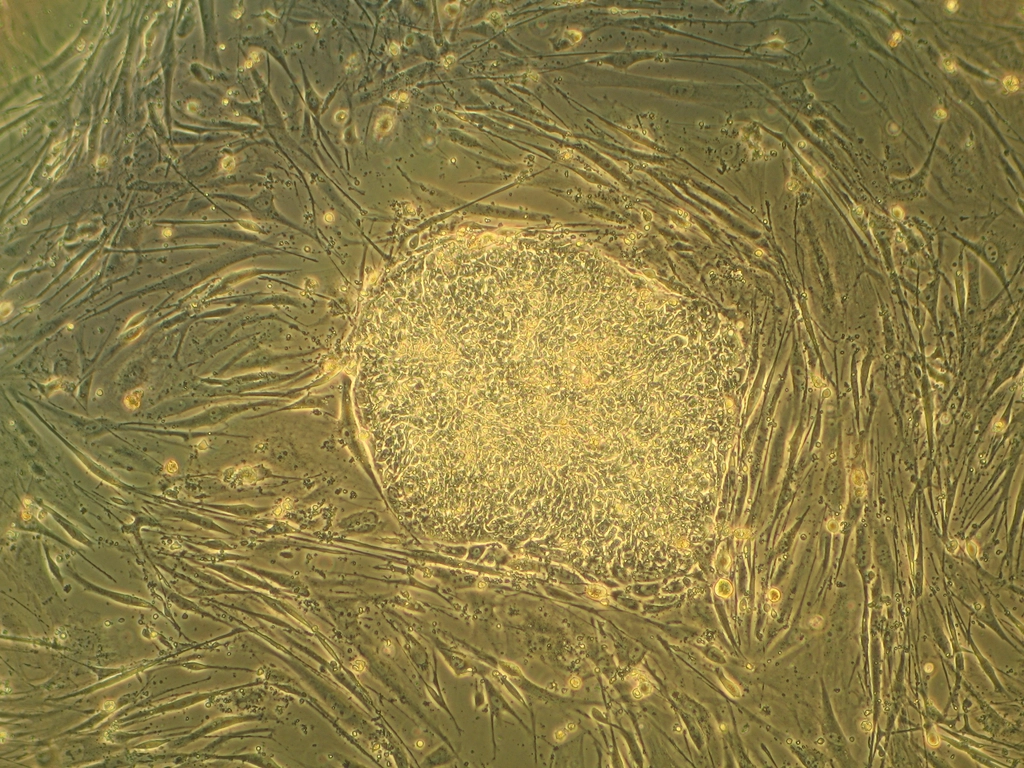

12. HeLa Cells The Immortal Contribution of Henrietta Lacks

In 1951, cells taken from Henrietta Lacks, a young African American woman with cervical cancer, became the first human cells to grow continuously in laboratory conditions. Dubbed “HeLa cells,” these remarkable cells never died under proper laboratory conditions, exhibiting a biological immortality that scientists had never before witnessed in human tissue. This unprecedented characteristic made HeLa cells invaluable to medical research, contributing to over 74,000 studies and numerous scientific breakthroughs, including the development of the polio vaccine, cancer treatments, and in vitro fertilization techniques. The cells were used without Lacks’ knowledge or consent—a bioethical issue that has since transformed research protocols and patient rights. Despite passing away shortly after her cells were harvested, Henrietta Lacks’ cellular legacy continues to save countless lives through medical advances that would have been impossible without her “immortal” contribution. The story of HeLa cells highlights not only scientific achievement but also raises important questions about medical ethics, informed consent, and racial disparities in healthcare that continue to resonate today.

11. Laika The First Animal in Orbit

Laika, a stray dog from the streets of Moscow, made history on November 3, 1957, when she became the first living creature to orbit Earth aboard the Soviet spacecraft Sputnik 2. This small mixed-breed dog was selected for her calm temperament and adaptability to confined spaces. Sadly, Laika’s mission was designed as a one-way trip, as the technology for a safe return to Earth did not yet exist. She survived for several hours in orbit before succumbing to stress and overheating, though for decades the Soviet Union claimed she lived for days. Laika’s journey provided crucial data about the effects of spaceflight on living organisms, demonstrating that a living passenger could survive launch and weightlessness. This information directly paved the way for human spaceflight, which followed just four years later when Yuri Gagarin became the first person in space. Laika’s sacrifice raised important questions about animal ethics in scientific research and exploration, while her story continues to symbolize both the ambition of the Space Race and its costs. Today, a monument stands in Moscow honoring this pioneering canine cosmonaut who helped humanity reach for the stars.

10. Drosophila melanogaster The Humble Fruit Fly

The common fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, may seem insignificant, but this tiny insect has been one of the most valuable model organisms in the history of genetic research. Thomas Hunt Morgan began working with fruit flies in the early 1900s at Columbia University, choosing them for their short six-day generation time, ease of breeding, and distinctive physical traits. Through his groundbreaking work with these insects, Morgan provided the first experimental evidence for the chromosome theory of inheritance, demonstrating that genes are carried on chromosomes and are the basis for inherited traits. Since then, fruit flies have contributed to countless scientific discoveries, including studies on aging, immunity, neurodegenerative diseases, and development. Their genome was fully sequenced in 2000, revealing that approximately 75% of human disease genes have a recognizable match in fruit flies, making them invaluable for modeling human disorders. The humble fruit fly continues to be used in laboratories worldwide, with over a century of accumulated knowledge making it one of science’s most well-understood and useful research organisms. Their contribution to our understanding of genetics and human biology is immeasurable, proving that even the smallest creatures can have an enormous scientific impact.

9. Pavlov’s Dogs Conditioning Human Understanding

In the 1890s, Russian physiologist Ivan Pavlov made a discovery that would transform our understanding of learning and behavior while studying the digestive system of dogs. Pavlov noticed that his laboratory dogs would begin to salivate not only when food was presented but also at the mere sound of his footsteps or the sight of the lab assistant who typically fed them. This observation led to his experiments on what he called “psychic reflexes,” now known as classical conditioning. By repeatedly pairing a neutral stimulus (such as a bell) with food, Pavlov demonstrated that dogs could be conditioned to salivate at the sound of the bell alone, even when no food was present. This groundbreaking work earned Pavlov the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1904 and established one of the fundamental principles of behavioral psychology. The concept of conditioned reflexes has influenced fields ranging from education and advertising to clinical psychology, where therapies for phobias and anxiety disorders often employ principles derived from Pavlov’s work. Although the names of his canine subjects have been lost to history, these dogs collectively revolutionized our understanding of how all animals—including humans—learn to associate stimuli with outcomes, cementing their place as crucial figures in the development of modern psychology.

8. Ham the Astrochimp Pioneering Primate Astronaut

Before humans ventured into space, NASA needed to ensure that the journey would be survivable. Enter Ham, a young chimpanzee who made history on January 31, 1961, as the first hominid in space. Named after the Holloman Aerospace Medical Center where he was trained, Ham was selected from a group of 40 chimpanzee candidates for his quick learning abilities and calm demeanor. During his 16-minute suborbital flight aboard the Mercury-Redstone 2 mission, Ham performed a series of tasks, proving that complex operations could be carried out in space conditions. He successfully completed these tasks by pulling levers in response to flashing lights, demonstrating that the stresses of spaceflight—including acceleration forces and weightlessness—would not significantly impair a passenger’s cognitive function or motor control. Despite experiencing higher G-forces than expected due to technical issues, Ham performed admirably, and his successful mission directly paved the way for Alan Shepard’s historic flight just three months later. After his space adventure, Ham lived at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., and later at the North Carolina Zoo, where he died in 1983 at age 26. His contribution to space exploration was invaluable, providing critical data that gave NASA the confidence to send humans beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

7. Harriet the Galápagos Tortoise Darwin’s Living Legacy

Harriet the Galápagos tortoise lived through three centuries, bearing witness to an extraordinary span of human history and scientific advancement. Collected as a young tortoise from the Galápagos Islands in 1835, reportedly by Charles Darwin himself during his voyage on HMS Beagle, Harriet became a living connection to the expeditions that inspired the theory of evolution. Though recent DNA analysis has suggested she came from an island Darwin didn’t visit, her species nevertheless exemplified the diversity that helped spark his revolutionary ideas. After spending time in Britain, Harriet was transported to Australia, where she lived at several locations before spending her final 17 years at Australia Zoo in Queensland. When she died in 2006 at the estimated age of 175, she was one of the oldest known animals in the world. Harriet’s extraordinary longevity provided scientists with valuable insights into aging, metabolism, and the remarkable adaptations that allow giant tortoises to survive for so long. As a representative of a species that directly influenced Darwin’s thinking, Harriet connected modern scientists to the foundations of evolutionary biology, making her not just a curiosity but a living laboratory for understanding both natural selection and extreme longevity.

6. Arabidopsis thaliana The Plant That Revolutionized Genetics

While not technically an animal, Arabidopsis thaliana, commonly known as thale cress or mouse-ear cress, deserves mention for its transformative impact on genetics and molecular biology. This small flowering plant from the mustard family became the first plant to have its entire genome sequenced in 2000, a milestone achievement that changed plant science forever. Scientists chose Arabidopsis as a model organism due to its remarkably small genome (about 135 million base pairs with approximately 27,000 genes), rapid life cycle (completing its entire life cycle in just six weeks), small size (allowing thousands to be grown in limited space), and prolific seed production. These characteristics made it ideal for genetic studies, particularly in understanding how genes control plant development and responses to environmental stresses. Research with Arabidopsis has led to fundamental discoveries about plant immunity, flowering time regulation, hormone signaling, and evolutionary development. Many of these findings have directly benefited agriculture by helping scientists develop crops with improved disease resistance, yield, and climate adaptability. Though humble in appearance, this little weed has become one of the most important organisms in biological research, with thousands of laboratories worldwide using it to address fundamental questions in plant biology that have applications far beyond its species.

5. Koko the Gorilla Breaking Communication Barriers

Koko, a western lowland gorilla born at the San Francisco Zoo in 1971, transformed our understanding of animal cognition and communication through her remarkable mastery of sign language. Under the guidance of researcher Francine “Penny” Patterson, Koko learned over 1,000 signs and could understand approximately 2,000 words of spoken English. Her demonstrated linguistic abilities challenged long-held assumptions about the cognitive and communicative capabilities of non-human animals. Koko famously asked for a cat as a pet, mourned when her kitten died, and showed complex emotions including empathy, humor, and grief. She scored between 70 and 95 on human IQ tests and created novel word combinations to express concepts for which she hadn’t learned specific signs, such as referring to a ring as a “finger bracelet.” Though some scientists debated whether Koko truly understood language or was responding to subtle cues, her documented abilities dramatically expanded our view of animal intelligence. When she died in 2018 at age 46, she left behind a legacy that fundamentally altered how scientists and the public perceive the mental lives of other species. Koko’s story continues to influence research in comparative psychology, linguistics, and animal cognition, reminding us that the gap between human and animal minds may be narrower than previously thought.

4. Alex the African Grey Parrot Avian Linguistic Genius

Alex, an African Grey parrot purchased from a pet store in 1977, became the subject of a groundbreaking 30-year experiment conducted by Dr. Irene Pepperberg at Harvard University that would fundamentally change our understanding of avian intelligence. Named as an acronym for “Avian Learning Experiment,” Alex demonstrated cognitive abilities previously thought impossible for non-primates. By the time of his unexpected death in 2007 at the age of 31, Alex had developed a vocabulary of over 100 words, could identify 50 different objects, recognize quantities up to six, understand the concept of “bigger,” “smaller,” “same,” and “different,” and distinguish seven colors and five shapes. Perhaps most impressively, he could combine these concepts, answering questions about objects’ properties with about 80% accuracy. Alex could express desires (“want grape”), refuse requests (“no”), and even showed signs of understanding zero as a concept—an ability previously only demonstrated in humans and some primates. On the evening before his death, Alex’s last words to Dr. Pepperberg were “You be good. I love you.” His cognitive achievements forced scientists to reconsider the neural basis of intelligence, suggesting that complex cognition doesn’t require a mammalian brain structure. Alex’s legacy continues through ongoing research with other African Grey parrots, and his accomplishments remain a powerful testament to the unexpected cognitive capabilities that may exist throughout the animal kingdom.

3. Washoe the Chimpanzee: Language Pioneer

Washoe, a female chimpanzee born in West Africa around 1965, became the first non-human to acquire human language when researchers Allen and Beatrix Gardner began teaching her American Sign Language (ASL) in 1966. Raised in an environment that treated her as much like a human child as possible, Washoe mastered approximately 350 signs and could combine them into meaningful phrases. What made her accomplishments particularly remarkable was her ability to spontaneously create new sign combinations for objects she hadn’t been explicitly taught, such as signing “water bird” upon seeing a swan for the first time. Even more compelling, Washoe passed her language skills to her adopted son, Loulis, without human intervention—the first documented case of an animal teaching human language to another animal. When shown her reflection, Washoe signed “me Washoe,” demonstrating self-awareness, and she expressed complex emotions through language, famously comforting a researcher who had suffered a miscarriage by signing “cry” when told about the loss. Until her death in 2007, Washoe continued to challenge conventional views about the uniqueness of human language capabilities. Her legacy lives on through ongoing studies of language acquisition in great apes, and she remains one of the most important animal subjects in the history of comparative psychology, having permanently altered our understanding of the cognitive and linguistic capabilities of our closest evolutionary relatives.

2. The Harvard Mouse First Patented Animal

In 1988, the scientific and legal worlds witnessed an unprecedented milestone when the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office granted the first-ever patent for a genetically modified animal. Known as the “Harvard Mouse” or “OncoMouse,” this laboratory mouse had been genetically engineered to carry a specific gene (an activated oncogene) that made it highly susceptible to developing cancer, particularly breast cancer. Developed by Harvard University researchers Philip Leder and Timothy Stewart, the mouse was designed as a valuable research model for studying cancer development, progression, and potential treatments. The landmark patent (US Patent No. 4,736,866) sparked global ethical and legal debates about the commercialization and ownership of living organisms. While the United States, Japan, and some European countries granted the patent, Canada’s Supreme Court ultimately rejected it, ruling that higher life forms could not be patented under Canadian law. Despite controversy, the Harvard Mouse pioneered a path for the development of countless other genetically modified animal models that have since become crucial tools in biomedical research. These specialized animals have accelerated our understanding of diseases ranging from cystic fibrosis to Alzheimer’s and have been instrumental in developing and testing new therapeutics. The case of the Harvard Mouse fundamentally changed both scientific practice and intellectual property law, creating a new category of research tools that continue to advance medical science while raising important questions about the ethical boundaries of biotechnology.

1. Enos the Space Chimp Testing the Mercury Capsule

Before astronaut John Glenn made history as the first American to orbit Earth, a brave chimpanzee named Enos took on the crucial role of testing the Mercury spacecraft in orbital conditions. On November 29, 1961, after 16 months of intensive training at Holloman Air Force Base, Enos launched aboard Mercury-Atlas 5. He had been taught to perform complex tasks—such as pulling levers in response to light cues—to demonstrate that living beings could maintain cognitive function and motor control in space. Enos completed two full orbits around Earth in just over three hours, providing NASA with essential data about spaceflight’s physical and psychological effects. Despite several technical issues during the mission—including a malfunctioning control system and failed reward-punishment apparatus—Enos completed his tasks under intense conditions, showing resilience and adaptability. His mission marked the final test before launching a human into orbit, giving scientists the confidence they needed to send John Glenn into space just months later. Enos’s courage and performance under pressure made him a key figure in the early days of space exploration. Though he returned safely, he died less than a year later. His contributions, however, remain embedded in the history of human spaceflight.

Conclusion:

The history of science is not written by humans alone. As this article illustrates, animals—whether as pioneers in space, unwitting contributors to genetic research, or subjects in psychological experiments—have profoundly shaped our understanding of biology, medicine, and the universe itself. From Laika’s historic journey into orbit to Dolly’s groundbreaking role in cloning, and from the linguistic brilliance of Koko and Alex to the genetic revelations made possible by fruit flies and mice, each of these animals has left an indelible mark on scientific progress. Their unique traits and often unchosen sacrifices have propelled discoveries that save lives, deepen knowledge, and challenge our ethical frameworks. Honoring their contributions is not just about acknowledging the past; it’s about recognizing the intertwined future of human and animal lives in the pursuit of knowledge. As we continue to explore the frontiers of science, let us carry forward a legacy of curiosity tempered with compassion, remembering the animals that helped us get here.

- These 12 Creatures Are More Lethal Than Sharks - August 23, 2025

- 10 Animals That Are Older Than Dinosaurs - August 23, 2025

- 11 Wild Creatures That Use Disguise - August 23, 2025