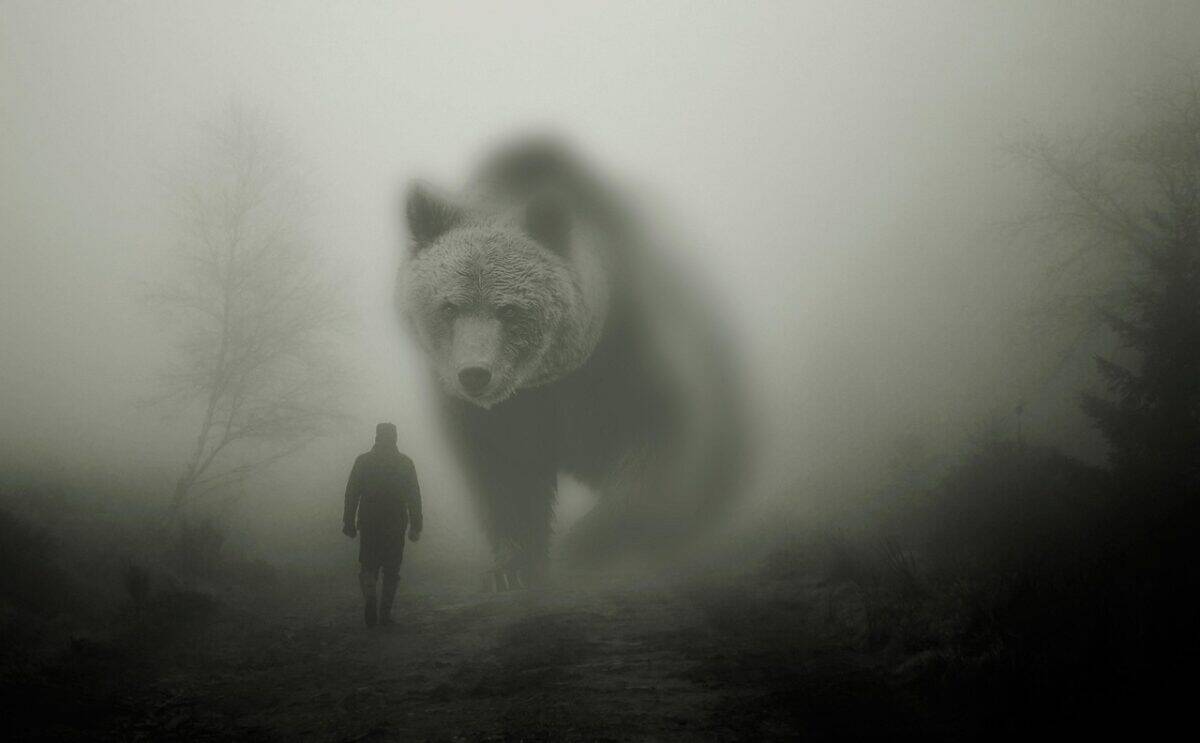

In wildlife management, few phrases carry as much significance as a bear becoming “habituated” to humans. This seemingly simple term represents a complex and often dangerous shift in natural bear behavior that has implications for both human safety and bear conservation. When wild bears lose their natural wariness of humans, they enter a precarious state that wildlife experts monitor with concern. Understanding bear habituation is crucial for anyone living in or visiting bear country, as it helps explain why wildlife authorities respond so seriously to bear-human interactions. This comprehensive guide explores what habituation means, how it develops, and why it matters to both bears and humans.

Defining Bear Habituation

Bear habituation refers to the process by which bears gradually lose their natural fear of humans through repeated, non-threatening exposure. A habituated bear no longer displays the normal avoidance behaviors typical of wild bears when encountering human presence, sounds, or scents. This represents a fundamental change in the animal’s natural behavior patterns. Unlike natural habituation to harmless environmental stimuli (like the sound of wind), habituation to humans specifically alters the healthy distance wild animals typically maintain from people. Wildlife biologists distinguish habituation from food conditioning, though the two often develop in tandem. A fully habituated bear may appear calm or indifferent around humans, which can create a dangerous false sense of security for people encountering these powerful predators.

The Habituation Process

Bear habituation doesn’t happen overnight but develops gradually through repeated non-threatening human encounters. The process typically begins when bears realize humans pose no immediate threat during casual encounters. For example, bears living near hiking trails may initially flee when hikers approach, but after numerous encounters where nothing negative happens, they gradually reduce their flight distance. Young bears learn habituation more quickly than adults, often by observing their mothers’ responses to humans. Environmental conditions also influence habituation rates—bears in areas with limited natural food sources may habituate faster when human food becomes available. Research shows that the habituation process can occur within a single season in high-traffic areas like national parks, where bears might encounter dozens of non-threatening humans daily. This learning process is adaptive in the sense that it reduces unnecessary energy expenditure from fleeing non-threatening stimuli, but it becomes maladaptive when it removes healthy fear of potentially dangerous human interactions.

Distinguishing Habituation from Food Conditioning

While often discussed together, habituation and food conditioning represent distinct behavioral changes in bears. Habituation solely refers to bears becoming comfortable with human presence, whereas food conditioning specifically involves bears learning to associate humans with food rewards. A bear can be habituated without being food conditioned—for instance, bears in some national parks may tolerate nearby photographers but still forage naturally. However, food conditioning almost always leads to habituation. When bears obtain human food or garbage, they quickly learn that humans equal easy calories, creating a powerful and dangerous association. The distinction matters because management strategies differ—habituated bears that aren’t food conditioned may sometimes coexist with humans under careful management, while food-conditioned bears almost always require more aggressive intervention. Wildlife officials consider food conditioning particularly problematic because it dramatically increases the likelihood of property damage and aggressive encounters as bears actively seek human sources of food.

How Human Behavior Creates Habituated Bears

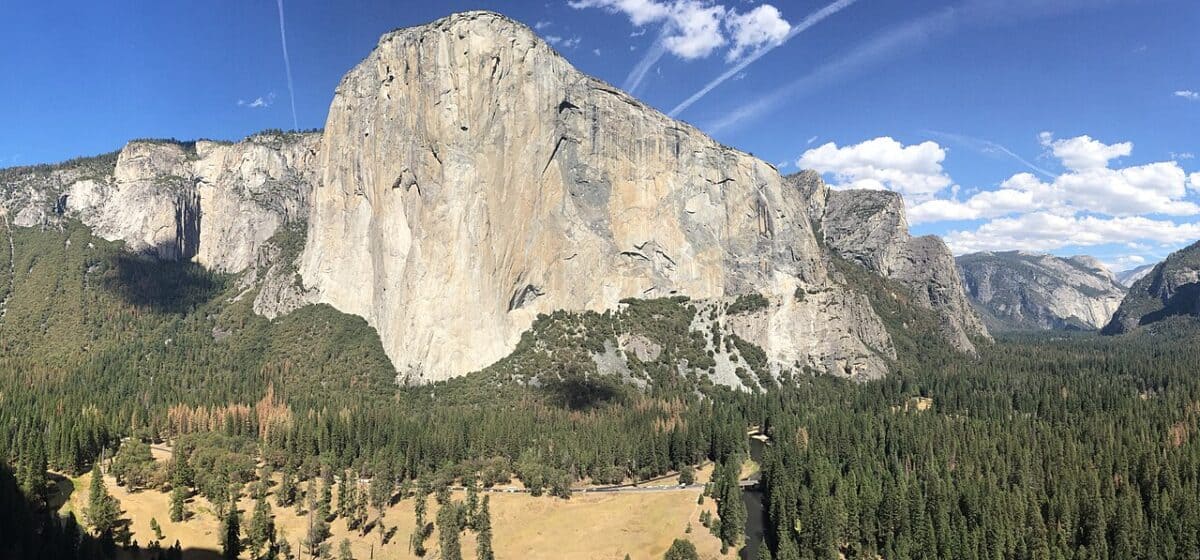

Human actions directly drive bear habituation, often unintentionally. Improper food storage stands as the primary culprit—when campers leave coolers accessible, homeowners put trash out the night before collection, or bird feeders remain filled during bear season, bears quickly learn to associate human spaces with easy meals. Even seemingly harmless behaviors contribute: tourists approaching bears for photos, hikers leaving food scraps on trails, or residents who enjoy watching bears visit their yards are all inadvertently teaching bears that proximity to humans is rewarding rather than dangerous. Research from Yosemite National Park found that bears can smell food from over a mile away and can remember food sources for years. One study documented a bear returning to a specific campsite three years after finding food there. These intelligent animals require just one successful food reward to begin the habituation process. The problem accelerates in tourist areas where different visitors make the same mistakes repeatedly, providing consistent reinforcement for bears’ problematic behaviors.

Signs of a Habituated Bear

Recognizing a habituated bear requires understanding normal wild bear behavior. Wild, non-habituated bears typically flee upon detecting humans, often before people even realize the bear was present. In contrast, habituated bears show distinctive behavioral changes: they may continue foraging or resting when humans approach; they maintain shorter flight distances; they appear visibly comfortable in human-dominated landscapes like yards, campgrounds, or roadsides; and they may look directly at humans without showing stress signals like huffing or paw swatting. Particularly concerning signs include bears that approach vehicles, peer into windows, or show interest in human structures. Body language offers important clues—habituated bears move more deliberately around humans rather than displaying the nervous, quick movements of wild bears. Wildlife officials monitor for temporal patterns too, as bears that are active during daylight hours in populated areas often show habituation, contrasting with the crepuscular (dawn/dusk) activity patterns of their wilder counterparts. Recognizing these signs early allows for intervention before more dangerous behaviors develop.

The Dangers to Humans

Habituated bears pose significant risks to human safety, though not always in ways people expect. Contrary to popular belief, most bear attacks don’t come from truly wild bears but from those habituated to human presence, particularly when food conditioning is involved. The danger stems from the unpredictability of close encounters—even normally docile black bears can become defensive if startled at close range, and a habituated bear’s comfort around humans creates more opportunities for such encounters. Statistics from the National Park Service show that the vast majority of bear-inflicted human injuries occur in situations involving habituated bears. Mothers with cubs present particular concerns, as habituated female bears may raise cubs in closer proximity to human areas, potentially leading to defensive aggression if people unknowingly approach the family. Property damage also represents a significant issue, with habituated bears causing millions in damages annually by breaking into vehicles, homes, and businesses in search of food. The risk escalates with each successful food reward, as bears become increasingly bold and potentially aggressive when humans attempt to deter them from known food sources.

The Consequences for Bears

While habituation threatens human safety, bears ultimately pay the higher price. The wildlife management adage “a fed bear is a dead bear” reflects the grim reality that habituated and food-conditioned bears frequently end up euthanized. Data from multiple state wildlife agencies indicate that habituated bears have significantly reduced lifespans compared to wild bears. In Colorado, for example, research shows that habituated bears live on average just 4-5 years, compared to 15-20 years for wild bears. Beyond direct management actions, habituated bears face increased mortality risks from vehicle collisions, ingestion of harmful human items, and higher likelihood of conflict with humans who may shoot them in self-defense. Nutritionally, human food often harms bears—processed foods provide poor nutrition compared to natural diets, and bears that become dependent on human sources may lose their natural foraging skills. Perhaps most concerning from a conservation perspective, female bears often teach habituation behaviors to their cubs, perpetuating the problem across generations and potentially affecting bear population dynamics in heavily human-influenced landscapes.

Geographic Hotspots for Bear Habituation

Bear habituation varies significantly by region, with certain geographic areas serving as habituation hotspots. National parks like Yosemite, Yellowstone, and Great Smoky Mountains experience high rates of bear habituation due to their combination of large bear populations and millions of annual visitors. Resort communities in states like Colorado, Montana, and California—where development pushes into bear habitat—report increasing problems with habituated bears. Tahoe, California has documented a 30% increase in bear incidents over the past decade as development has expanded. Alaska presents a unique case, with popular viewing areas like Brooks Falls in Katmai National Park featuring bears that tolerate human observers while maintaining natural foraging behaviors—a managed form of habituation that researchers monitor carefully. Urban-wilderness interfaces present particular challenges; cities like Asheville, North Carolina and Gatlinburg, Tennessee report hundreds of habituated bear encounters annually. Climate change and drought have exacerbated the issue in many regions, as bears increasingly seek human food sources when natural foods become scarce. These geographic patterns help wildlife officials target prevention and education efforts where they’re most needed.

Management Approaches for Habituated Bears

Wildlife authorities employ various strategies to manage habituated bears, following a progressive approach based on the animal’s behavior and habituation level. For bears showing early signs of habituation, aversive conditioning serves as the first intervention—using loud noises, rubber bullets, or specially trained dogs to restore fear of humans. These methods prove most effective when applied consistently and early in the habituation process. Trap-and-relocate programs, once common, show limited long-term success, with studies indicating that up to 70% of relocated bears either return to their original territory or create similar problems in new locations. For bears exhibiting dangerous behaviors or repeated food conditioning, euthanasia often becomes the reluctant final option for wildlife managers prioritizing public safety. More innovative approaches include electrical deterrents around attractants, community-wide food storage programs, and bear-resistant infrastructure in high-conflict areas. Management approaches vary by jurisdiction and bear species—grizzly/brown bears typically receive more aggressive intervention earlier due to their greater potential danger to humans, while black bears may receive more opportunities for behavioral correction before lethal measures are considered.

Prevention: The Community Approach

Preventing bear habituation requires community-wide commitment rather than individual actions alone. Research shows that even when 90% of a community properly secures attractants, the remaining 10% can create enough food rewards to habituate local bears. Successful prevention programs like those in Whistler, British Columbia combine several approaches: comprehensive bear-resistant garbage systems; municipal ordinances with meaningful fines for non-compliance; educational programs in schools and for new residents; and community reporting systems to identify problem areas quickly. Timing matters significantly—communities that implement preventive measures before bears become habituated show much higher success rates than those reacting to established habituation. The economic case for prevention is compelling—Yosemite National Park’s investment of $500,000 in bear-resistant food lockers reduced bear incidents by 95%, saving millions in property damage and management costs. Beyond infrastructure, changing human behavior through education represents a crucial component, with research showing that targeted messaging about bear biology and behavior increases compliance with proper food storage by 40% compared to simple directive signage. Community-based prevention acknowledges that bear habituation represents a human-caused problem requiring human solutions.

The Science of De-habituation

Can habituated bears return to wild behavior? Research on de-habituation—the process of restoring natural wariness in habituated bears—shows mixed results. Studies from Washington State University indicate that success depends heavily on the bear’s age and the degree of habituation. Young bears with limited habituation show the highest reversal potential, while older bears with years of food conditioning rarely return to fully wild behavior. The timing and intensity of aversive conditioning play crucial roles—consistent negative experiences associated with human areas must outweigh the bear’s memory of food rewards. Wildlife biologists use increasingly sophisticated approaches, including training bears to associate specific human sounds with negative consequences before they encounter the actual stimulus. Physiological factors also influence outcomes, as bears’ exceptional spatial memory and annual cycles affect learning patterns. Bears approaching hyperphagia (the intensive pre-hibernation feeding period) prove particularly difficult to de-habituate due to their biological imperative to maximize caloric intake. While complete de-habituation of strongly food-conditioned bears remains rare, research continues on more effective techniques, including the use of specialized scent deterrents and behavior modification approaches adapted from work with other large predators.

Ethical Considerations in Bear Management

The management of habituated bears raises significant ethical questions that balance human safety, animal welfare, and ecosystem integrity. Wildlife professionals increasingly recognize that humans bear primary responsibility for creating habituation, complicating decisions about lethal management of “problem” bears. Conservation ethicists question whether it’s morally justifiable to euthanize animals for exhibiting behaviors humans inadvertently taught them. This ethical tension becomes particularly acute with bears protected under endangered species legislation or in areas where bear populations face other threats. Indigenous perspectives often bring important additional considerations—many Native American and First Nations communities view bears as relatives rather than problems to be managed, advocating for approaches that respect the animals’ inherent value while protecting human communities. The ethical calculus also involves intergenerational responsibility, as decisions about managing today’s habituated bears affect future wildlife-human relationships. Modern wildlife management increasingly incorporates these ethical dimensions alongside scientific data, recognizing that effective solutions must address not just the immediate problem of habituated bears but the underlying human behaviors and values that create and perpetuate these situations.

Bear habituation represents one of the most significant challenges in human-wildlife coexistence, requiring a delicate balance between human safety and wildlife conservation. The science clearly shows that preventing habituation serves both bears and humans better than managing its consequences. As human populations continue expanding into bear habitat, our collective responsibility for preventing habituation becomes increasingly important. Each individual action—properly storing food while camping, securing garbage at home, maintaining appropriate distances during wildlife viewing—contributes to the larger goal of keeping bears wild and people safe. The fate of bears in human-dominated landscapes ultimately depends not on the bears’ ability to adapt to us, but on our willingness to adapt our behaviors to accommodate their natural needs and instincts. By understanding what habituation means and taking proactive steps to prevent it, we can work toward a future where bears retain their wild nature while humans enjoy the privilege of sharing landscapes with these magnificent animals.

- The Coldest Town in America—And How People Survive There - August 9, 2025

- How Some Birds “Steal” Parenting Duties From Others - August 9, 2025

- 12 Deep-Sea Creatures You Won’t Believe Exist - August 9, 2025