In the murky depths of the Mississippi River and its tributaries, a silent crisis unfolds as freshwater mussels—often overlooked yet ecologically vital—face unprecedented threats to their survival. These remarkable filter-feeders, which have inhabited North American waterways for millions of years, now stand at a critical crossroads. The Mississippi River Basin, once home to the world’s most diverse mussel populations with over 300 species, has witnessed alarming declines, with dozens of species already extinct and many more teetering on the brink. This ecological emergency isn’t merely about losing unique creatures—it represents the unraveling of aquatic ecosystems that support human communities, economies, and water quality throughout America’s heartland. As we explore the fascinating world of these endangered mollusks and the dedicated efforts to save them, we uncover a compelling story of resilience, scientific ingenuity, and hope for the future of our most iconic river system.

The Hidden Ecological Engineers of the Mississippi

Freshwater mussels are among nature’s most efficient ecosystem engineers, yet they remain largely invisible to the public eye. These unassuming bivalves—some living up to a century—perform critical ecological functions in the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Each adult mussel filters up to 15 gallons of water daily, removing algae, bacteria, and pollutants while simultaneously improving water clarity and quality. This natural filtration service provides benefits that would cost billions if replicated through human technology.

Beyond water purification, mussels create habitat complexity through their shells, both during their lives and after death. Their presence stabilizes river bottoms, provides shelter for small aquatic organisms, and cycles nutrients through the ecosystem. Scientists have documented higher biodiversity in areas with healthy mussel populations, highlighting their role as keystone species. The Mississippi Basin once supported over 300 species of freshwater mussels—representing the richest mussel fauna on Earth—with each species adapted to specific ecological niches within the river’s complex habitats.

A Crisis of Extinction: Current Status and Threats

The freshwater mussels of the Mississippi River system face a dire situation. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, approximately 70% of North American freshwater mussel species are either endangered, threatened, or of special concern. Since the early 20th century, at least 35 species have gone extinct, with the Mississippi Basin suffering the highest losses. Notable extinctions include the once-abundant Ebonyshell and the striking Winged Mapleleaf, which has disappeared from over 90% of its historical range.

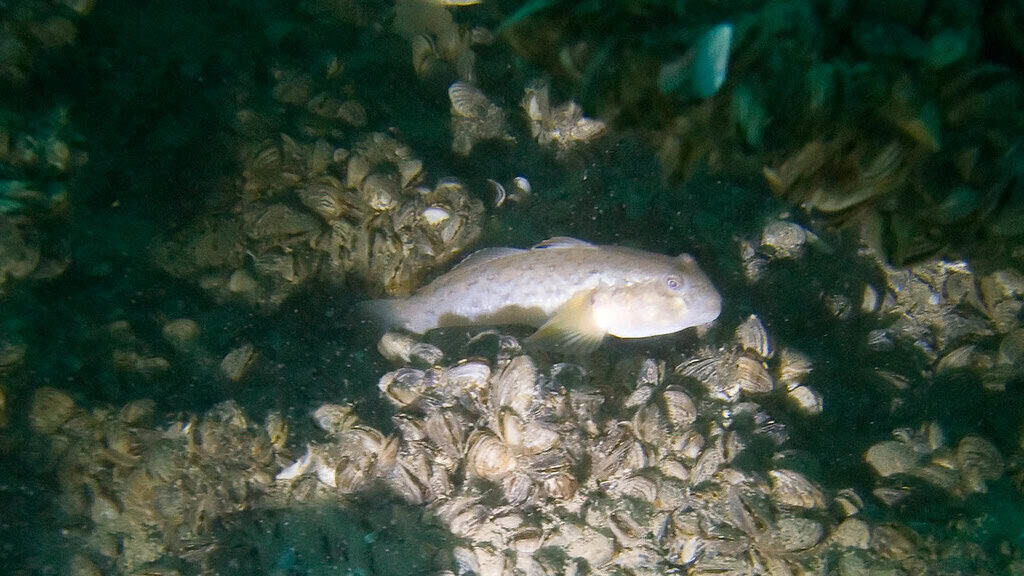

Multiple threats converge to imperil these sensitive organisms. Dam construction has fundamentally altered river flow patterns and blocked the movement of host fish that mussels depend on for reproduction. Agricultural runoff introduces excess nutrients, pesticides, and sediments that smother mussel beds. Industrial pollution, including heavy metals and emerging contaminants, disrupts mussel reproduction and growth. Climate change intensifies these stressors through altered precipitation patterns, increased water temperatures, and more frequent drought events. Adding to these challenges, invasive species—particularly the zebra mussel—outcompete and physically smother native mussel communities, accelerating their decline across large portions of the watershed.

The Remarkable Life Cycle of Freshwater Mussels

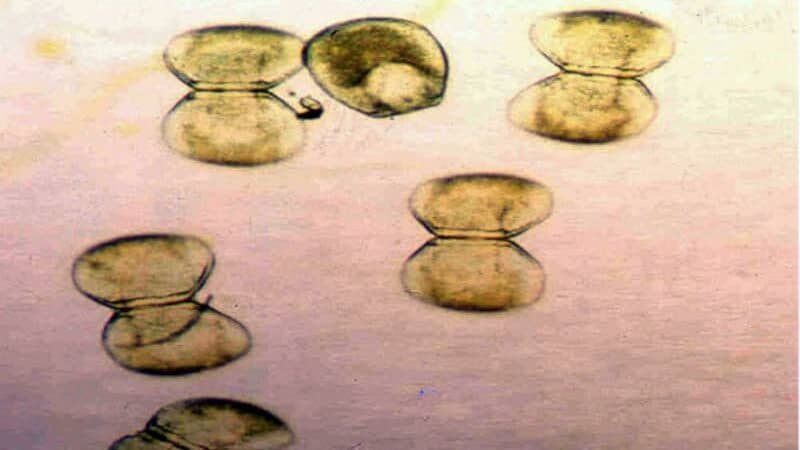

The reproductive strategy of freshwater mussels ranks among nature’s most fascinating evolutionary adaptations. Unlike most aquatic creatures, mussels employ an extraordinary parasitic phase in their life cycle. The process begins when male mussels release sperm into the water column, which females filter from the water to fertilize their eggs. The fertilized eggs develop into microscopic larvae called glochidia within specialized chambers in the female’s gills. What happens next showcases evolutionary ingenuity: the mother mussel must transfer these larvae to specific fish species that serve as temporary hosts.

To accomplish this feat, different mussel species have evolved elaborate lures that mimic small fish, crayfish, or aquatic insects. When a potential host fish investigates the convincing lure, the female mussel expels clouds of glochidia, which attach to the fish’s gills or fins. The larvae then encyst in the fish’s tissues for weeks or months, drawing nutrients while transforming into juvenile mussels. Eventually, they detach and fall to the river bottom to begin independent life. This complex reproduction requires precise timing and the presence of specific host fish species—a delicate balance easily disrupted by environmental changes. For conservation efforts to succeed, this intricate life cycle must be understood and preserved in all its complexity.

Historical Abundance and Cultural Significance

Before European settlement, the Mississippi River system teemed with freshwater mussels in numbers difficult to comprehend today. Historical accounts describe river bottoms literally paved with shells, with biomass estimates suggesting densities of over 100 mussels per square meter in prime habitats. Native American cultures along the Mississippi utilized mussels extensively for food, tools, and ceremonial purposes for thousands of years. Archaeological sites throughout the basin contain middens—ancient shell piles—testifying to their importance in sustaining riverine communities. Indigenous craftspeople transformed mussel shells into spoons, scrapers, hoes, and decorative items.

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw the rise of the pearl button industry, which harvested billions of mussels from the Mississippi and its tributaries. At its peak around 1912, this industry employed over 20,000 people across dozens of river towns, with factories producing 1.5 billion buttons annually—nearly 40% of the world’s button supply. By the 1940s, overharvesting had depleted many mussel beds, and plastic buttons eventually replaced shell. This commercial exploitation, while economically important, contributed significantly to mussel declines. Today, freshwater mussels maintain cultural significance through their role in traditional ecological knowledge and as indicators of river health for communities dependent on the Mississippi for livelihoods, recreation, and spiritual connection.

Canaries in the Coal Mine: Mussels as Ecological Indicators

Freshwater mussels serve as exceptional bioindicators of aquatic ecosystem health, functioning much like canaries once did in coal mines. Their sedentary lifestyle, long lifespan, and filter-feeding habits make them particularly sensitive to environmental changes and pollutants. When mussel populations decline, it often signals broader ecological problems that may eventually affect fish, wildlife, and human health. Scientists regularly monitor mussel diversity and abundance as part of water quality assessment programs throughout the Mississippi Basin. The presence of rare or sensitive species, such as the Spectaclecase or Fat Pocketbook mussel, indicates excellent water quality and ecosystem function.

Beyond their indicator value, mussels bioaccumulate contaminants in their tissues and shells, creating a physical record of pollution history in a waterway. Researchers analyze growth rings in mussel shells—similar to tree rings—to reconstruct historical water quality conditions dating back decades. This information helps establish baseline conditions for restoration efforts and identifies pollution sources. For communities along the Mississippi dependent on the river for drinking water, recreation, and economic activity, healthy mussel populations represent nature’s first line of defense against deteriorating water quality. As municipalities invest millions in water treatment infrastructure, the ecosystem services provided by mussels gain increasing recognition among water resource managers and public health officials.

Conservation Hatcheries: Creating Mussel Arks

Specialized conservation hatcheries have emerged as crucial lifelines for endangered mussel species across the Mississippi Basin. These facilities, operated by federal agencies, state conservation departments, and university partners, function as modern-day arks preserving genetic diversity while researchers address threats in natural habitats. The process begins with collecting a small number of adult mussels from remnant wild populations. In controlled laboratory settings, scientists replicate the complex life cycle by exposing the appropriate host fish species to the mussel larvae. After metamorphosis, juvenile mussels are carefully raised in sophisticated recirculating systems that mimic natural river conditions.

The Genoa National Fish Hatchery in Wisconsin stands as a leader in this field, producing hundreds of thousands of juvenile mussels annually representing dozens of endangered species. Similar facilities in Missouri, Tennessee, and Kentucky focus on regionally important species. These hatchery programs have achieved remarkable successes, including preventing the extinction of the Higgins’ Eye Pearlymussel and the Pink Mucket—both once abundant throughout the Mississippi system. Genetic management remains a priority, with researchers maintaining detailed pedigrees to maximize genetic diversity in captive populations. When conditions in restoration sites improve sufficiently, hatchery-raised mussels are reintroduced to carefully selected locations, often within specially designed refugia that provide protection from invasive species and changing river conditions.

Dam Removal and Flow Restoration Efforts

The Mississippi River system contains over 40,000 dams, from massive navigation structures on the main stem to small barriers on tributaries, collectively representing one of the most significant threats to mussel survival. Dams disrupt natural flow regimes, alter temperature patterns, trap sediments, and block host fish movements essential for mussel reproduction. In recent decades, a growing movement to remove obsolete or harmful dams has gained momentum, with over 1,200 dam removal projects completed nationwide. Notable successes within the Mississippi Basin include the removal of the Woodside Dam on Wisconsin’s Pecatonica River, which reconnected over 100 miles of habitat and led to significant mussel recolonization.

Where dams cannot be removed due to flood control or power generation requirements, innovative approaches to flow management have been implemented. Environmental flow releases—scheduled water discharges that mimic natural seasonal patterns—have shown promise in supporting mussel reproduction and survival. On the Tennessee River system, the Tennessee Valley Authority has modified operations at multiple dams to ensure minimum flows and appropriate temperature regimes for endangered mussel species. The Nature Conservancy’s Sustainable Rivers Program works with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to implement similar flow modifications on regulated reaches throughout the Mississippi Basin. These efforts demonstrate that water infrastructure operation can balance human needs with ecological requirements, providing a model for river management that supports both healthy mussel populations and human communities.

Watershed Protection and Agricultural Partnerships

Since agricultural runoff represents one of the primary threats to freshwater mussels, innovative partnerships between conservation organizations and farming communities have become essential for recovery efforts. The Mississippi River Basin Healthy Watersheds Initiative, launched in 2009, has invested over $300 million in conservation practices that reduce nutrient and sediment loading while improving farm productivity. Participating farmers implement precision fertilizer application, cover crops, and riparian buffers—practices that benefit both agricultural operations and downstream water quality. In Iowa and Minnesota, where tile drainage systems rapidly transport agricultural chemicals to waterways, constructed wetlands now intercept and filter this runoff before it reaches mussel habitats.

Local watershed organizations play crucial roles in these efforts by building relationships with landowners and connecting them with technical and financial assistance. The Fishers and Farmers Partnership focuses specifically on agricultural watersheds containing endangered aquatic species, including freshwater mussels. Their “pay-for-performance” approach compensates farmers based on measured water quality improvements rather than simply implementing practices. This results-oriented strategy has reduced phosphorus loading by up to 30% in priority watersheds. Conservation easements along critical stream corridors provide permanent protection for riparian zones adjacent to important mussel beds. Together, these watershed-scale approaches address the root causes of mussel decline while supporting the economic viability of agricultural communities throughout the Mississippi Basin.

Innovative Research and Monitoring Technologies

The field of freshwater mussel conservation has been transformed by technological innovations that enhance researchers’ ability to detect, monitor, and protect these elusive creatures. Environmental DNA (eDNA) sampling allows scientists to detect mussel presence by analyzing water samples for trace genetic material, revealing populations in remote locations without disturbing river habitats. This technology has documented previously unknown populations of rare species like the Salamander Mussel in small tributaries throughout the Mississippi system. Advances in radio telemetry and passive integrated transponder (PIT) tags enable researchers to track individual mussels’ movements and survival over extended periods, providing unprecedented insights into habitat preferences and behavior patterns.

Genomic tools have revolutionized conservation breeding programs by identifying distinct evolutionary lineages within species and informing genetic management decisions. Using next-generation sequencing, researchers can maintain appropriate genetic diversity in reintroduction efforts and identify populations with adaptive traits that might enhance resilience to climate change. Sophisticated water quality sensors deployed throughout the Mississippi Basin provide real-time data on conditions affecting mussel survival, allowing for rapid response to pollution events or harmful changes in flow conditions. These technologies, combined with traditional field surveys conducted by trained biologists and volunteer citizen scientists, create a comprehensive monitoring network that guides conservation decisions and measures progress toward recovery goals for endangered mussel species.

Public Engagement and Citizen Science

Raising public awareness about freshwater mussels presents unique challenges—these animals lack the charismatic appeal of many endangered species and spend most of their lives buried in river sediments. Yet successful conservation requires public support and involvement. Innovative education programs throughout the Mississippi Basin have begun to transform public perception of mussels. The National Mississippi River Museum in Dubuque, Iowa features interactive exhibits showcasing mussel diversity and ecological importance. Mobile aquarium displays travel to schools and community events, allowing people to observe live mussels filtering water—a powerful demonstration of their ecosystem services.

Citizen science initiatives engage volunteers in meaningful conservation work while building public investment in mussel recovery. The Freshwater Mussel Conservation Alliance trains community members to conduct streamside surveys, monitor water quality, and report mussel die-offs. In Tennessee and Kentucky, the “Mussel Watchers” program involves high school students in monitoring reintroduced populations as part of their science curriculum. Volunteer-led “mussel blitzes” bring together dozens of citizens for intensive survey efforts that cover extensive river reaches in a single day. These participatory approaches not only generate valuable scientific data but also create a constituency of informed advocates for mussel conservation. Social media campaigns highlighting the extraordinary life cycles and ecological benefits of mussels reach audiences beyond traditional conservation circles, gradually building a broader base of support for protection efforts throughout the Mississippi watershed.

Legal Protections and Policy Frameworks

The legal foundation for freshwater mussel conservation rests primarily on the Endangered Species Act (ESA), which currently protects 88 mussel species nationwide, with the majority occurring in the Mississippi Basin. This federal legislation prohibits “take” of listed species, requires federal agencies to avoid actions that would jeopardize their survival, and mandates development of recovery plans with specific conservation objectives. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has designated thousands of river miles as critical habitat for endangered mussels, providing additional protections for these areas. Complementary state endangered species laws offer protection for species of regional concern that may not meet federal listing criteria.

Beyond species-specific protections, broader environmental laws benefit mussel conservation through habitat and water quality improvements. The Clean Water Act regulates pollutant discharges and requires states to establish water quality standards that support aquatic life, including sensitive mussel species. Recent legal victories have strengthened implementation of these protections, including a landmark 2015 court decision requiring the Environmental Protection Agency to address agricultural nutrient pollution in the Mississippi Basin more aggressively. Conservation organizations frequently use these legal frameworks to challenge permits for activities that would harm mussel populations, such as pipeline crossings or shoreline development. While enforcement challenges remain, especially for diffuse pollution sources, these legal tools provide essential backstops against further mussel declines and leverage for negotiating conservation agreements with industries and municipalities throughout the watershed.

Despite the challenges facing freshwater mussels, targeted conservation efforts have produced remarkable success stories throughout the Mississippi Basin. The Higgins’ Eye Pearlymussel, once on the brink of extinction due to zebra mussel invasions, now thrives in carefully selected reintroduction sites in the Upper Mississippi. Intensive propagation efforts produced over 40,000 juvenile mussels that were strategically placed in locations with appropriate habitat and minimal invasive species presence. Monitoring shows these populations now successfully reproducing naturally—a crucial milestone in recovery. In Tennessee’s Duck River, water quality improvements and flow management changes have allowed the river to maintain all 56 native mussel species—a global hotspot for mussel diversity that demonstrates how recovery is possible with sustained conservation attention.

Collaborative watershed restoration in Iowa’s Boone River has reduced sediment loads by 23% and significantly decreased nitrogen runoff through farmer-led conservation practices. The improved water quality has benefited the Plain Pocketbook and other sensitive mussel species that had disappeared from the system decades ago but now show signs of recovery. Perhaps most encouraging, several species once thought extinct have been rediscovered through intensive surveys. The Salamander Mussel, not seen alive for 50 years, was found in a remote

- America’s Most Endangered Mammals And How to Help - August 9, 2025

- The Coldest Town in America—And How People Survive There - August 9, 2025

- How Some Birds “Steal” Parenting Duties From Others - August 9, 2025