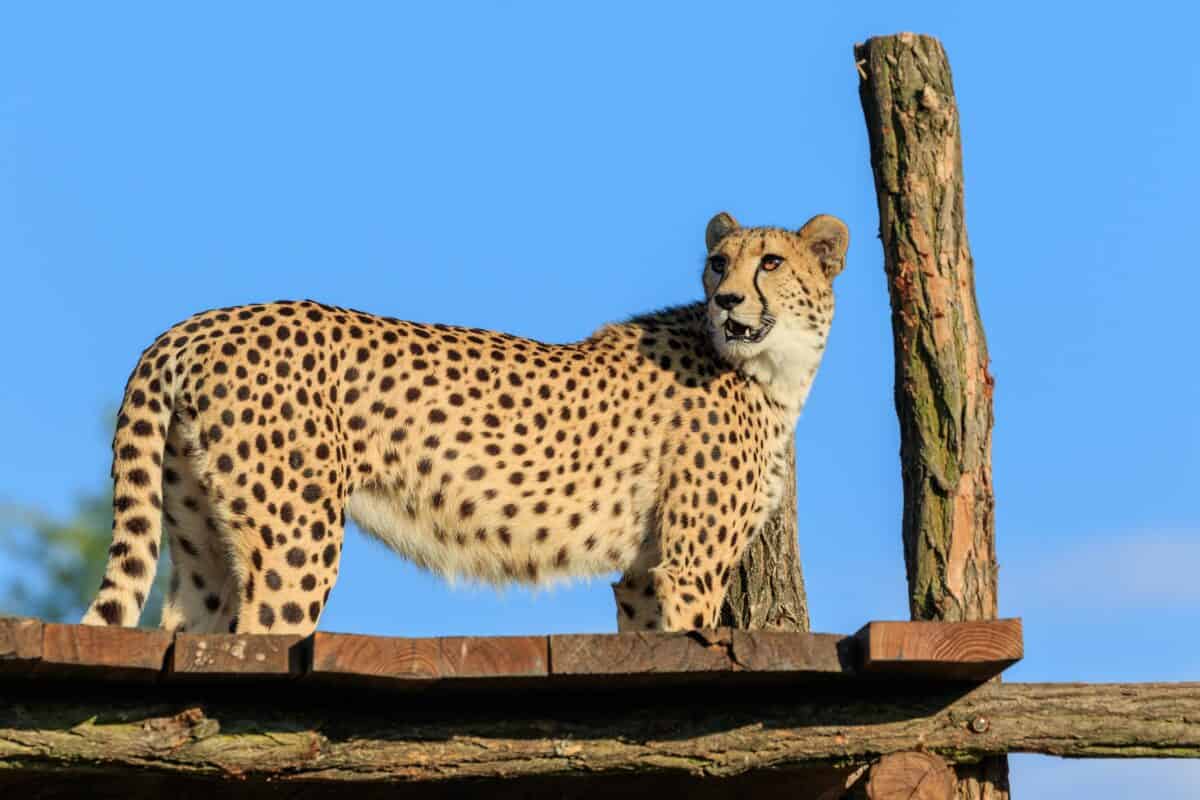

The cheetah, nature’s speed marvel capable of reaching 70 mph in mere seconds, faces a precarious future. Once roaming widely across Africa and parts of Asia, these magnificent cats have lost over 90% of their historic range. Today, with fewer than 7,000 cheetahs remaining in the wild, conservationists are racing against time to prevent their extinction. This dramatic decline isn’t happening randomly—specific, identifiable threats are driving cheetahs toward an uncertain future. Understanding these challenges is the first crucial step in developing effective conservation strategies to ensure these remarkable predators continue to sprint across the savannas for generations to come.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

The single most significant threat to cheetah survival is the relentless loss and fragmentation of their habitat. Human population growth has led to the conversion of vast grasslands—the cheetah’s prime hunting grounds—into agricultural fields, urban developments, and industrial zones. Unlike other big cats that can adapt to varied environments, cheetahs require large, open spaces to hunt effectively using their remarkable speed. Research indicates that a single cheetah may need up to 800 square kilometers of territory to thrive.

This habitat fragmentation creates isolated cheetah populations, trapped in habitat islands and unable to connect with other groups. The resulting genetic isolation leads to inbreeding, which diminishes genetic diversity and makes populations more vulnerable to disease and environmental changes. In East Africa alone, cheetah habitat has shrunk by more than 75% over the past century, while in Asia, the species has been reduced to a single small population in Iran, highlighting the severity of this crisis.

Human-Wildlife Conflict

As human settlements expand into traditional cheetah territories, direct conflict between farmers and these predators has intensified. Unlike lions, which typically hunt at night, cheetahs are diurnal hunters, making them more likely to encounter humans and their livestock during daylight hours. When cheetahs prey on livestock—often out of necessity as their natural prey becomes scarce—they face lethal retaliation from farmers protecting their livelihoods. Studies in Namibia have documented that up to 90% of cheetah deaths in some regions result from retaliatory killings by farmers.

The economic reality is stark: a single livestock loss can represent a significant financial blow to subsistence farmers, making tolerance for predators understandably low. Traditional farming practices often lack adequate protective measures for livestock, creating a cycle of predation and retaliation that has devastating consequences for cheetah populations. The situation is exacerbated by the fact that cheetahs, unlike some other predators, rarely return to feed on their kills, meaning they must hunt more frequently, increasing potential conflicts with humans.

Prey Base Depletion

Cheetahs rely on a healthy population of medium-sized ungulates like gazelles and impalas for survival. However, these prey species face their own crisis due to habitat loss, competition with livestock for grazing lands, and unsustainable hunting practices. In many regions across Africa, wild ungulate populations have declined by over 50% in recent decades. This prey scarcity forces cheetahs to expand their hunting territories, expend more energy searching for food, and take greater risks—including venturing closer to human settlements where they might target livestock.

The nutritional stress from insufficient prey affects not just individual survival but also reproductive success. Female cheetahs require optimal nutrition to successfully reproduce and care for cubs. Studies show that in areas with depleted prey, cheetah reproduction rates drop significantly, with fewer cubs surviving to adulthood. Additionally, hungry cheetahs may be forced to hunt in suboptimal conditions, increasing their vulnerability to other predators and reducing their overall fitness, creating a downward spiral for already struggling populations.

High Cub Mortality

Even under ideal conditions, cheetah cubs face daunting survival odds. In the wild, approximately 70-80% of cheetah cubs don’t survive their first year of life. This high mortality rate stems from multiple factors, including predation by lions, hyenas, and other carnivores. Lions, in particular, will actively hunt and kill cheetah cubs to eliminate future competition. Unlike other big cats, female cheetahs don’t have the strength to defend their young against larger predators, often being forced to abandon cubs when threatened.

Disease and malnutrition further compound the problem, especially in areas where prey is scarce. Cheetah mothers must leave their cubs hidden and vulnerable while hunting, sometimes for hours at a time. This extended separation increases predation risk and exposure to harsh environmental conditions. The situation is particularly dire in fragmented habitats, where higher densities of predators and limited escape options create death traps for vulnerable cubs. This naturally high mortality rate, exacerbated by human-caused threats, creates a significant barrier to population recovery.

Genetic Vulnerability

Modern cheetahs carry the genetic legacy of a severe population bottleneck that occurred approximately 12,000 years ago, at the end of the last ice age. This prehistoric near-extinction event left all surviving cheetahs with remarkably similar genetic profiles—essentially making today’s cheetahs more genetically similar than if they were siblings. This extreme genetic uniformity makes them particularly vulnerable to disease outbreaks, as a pathogen that can affect one cheetah is likely to affect all of them similarly, with few individuals possessing potentially resistant genetic variations.

The limited genetic diversity also manifests in reduced reproductive fitness, including higher rates of abnormal sperm in males (up to 70% compared to about 30% in other cats) and smaller litter sizes. When habitat fragmentation further isolates small populations, inbreeding depression intensifies these problems. Conservation geneticists warn that without careful management to maximize remaining genetic diversity, even populations that seem stable in numbers could collapse rapidly in the face of new environmental challenges or disease outbreaks, highlighting the hidden vulnerability beneath even seemingly healthy cheetah groups.

Illegal Wildlife Trade

While not as heavily targeted as elephants or rhinos, cheetahs face a significant threat from the illegal wildlife trade. In particular, the demand for exotic pets has created a cruel market for cheetah cubs, especially in the Gulf States. Traffickers capture cubs from the wild, often killing the mother in the process, and smuggle them through the Horn of Africa to wealthy buyers. The Cheetah Conservation Fund estimates that up to 300 cubs are trafficked annually from the region, primarily from populations in Ethiopia, Somalia, and northern Kenya that can ill afford such losses.

Once in captivity, these cubs face dismal prospects. Most die during transport or shortly after arrival due to improper care, malnutrition, and stress. Those that survive typically develop serious health issues, including metabolic bone disease from improper diet and psychological disorders from inadequate stimulation. Even when authorities manage to confiscate trafficked cubs, rehabilitation is challenging, and most can never be returned to the wild. The combined impact of mothers killed, cubs removed, and the disruption to social structures represents a severe threat, particularly to the already vulnerable populations in East Africa.

Climate Change

The accelerating climate crisis poses existential challenges for cheetahs, whose specialized physiology makes them particularly vulnerable to environmental changes. Rising temperatures affect hunting behavior, as cheetahs must balance the energy expenditure of high-speed chases with the risk of overheating. Research indicates that cheetahs already hunt primarily during cooler morning and evening hours; as temperatures rise, their hunting windows narrow further, potentially reducing hunting success and increasing nutritional stress.

Climate change also disrupts rainfall patterns, leading to more frequent and severe droughts in many cheetah habitats. These droughts diminish vegetation, reducing prey populations and intensifying competition with other predators and livestock for dwindling resources. Additionally, changing climatic conditions may alter the distribution of diseases and parasites, potentially introducing new health threats to already vulnerable cheetah populations. Unlike more adaptable species, cheetahs’ specialized niche and already reduced habitat options leave them with limited capacity to shift their range in response to changing conditions, making climate change a slow but inexorable threat to their survival.

Road Mortality

As infrastructure development expands across Africa, roads increasingly bisect cheetah habitats, creating deadly barriers to movement and direct mortality risks. Cheetahs routinely cross roads during territorial patrols and hunting, making them vulnerable to vehicle collisions. In areas with higher traffic volumes, such as Namibia’s main highways and South Africa’s national parks, road kills have become a significant source of cheetah mortality. A study in the Kruger National Park found that approximately 10% of cheetah deaths were attributed to vehicle collisions, a figure that rises in more heavily trafficked areas.

Beyond direct mortality, roads fragment habitats and disrupt movement patterns, affecting cheetahs’ ability to locate prey, find mates, and establish territories. Roads also facilitate human access to previously remote areas, increasing poaching opportunities and habitat disturbance. The psychological impact of busy roads creates “barrier effects,” with some cheetahs avoiding crossing entirely, further isolating populations and reducing genetic exchange. As African nations continue ambitious infrastructure development plans, including the expansion of transcontinental highways, this threat is likely to intensify without careful planning and mitigation measures.

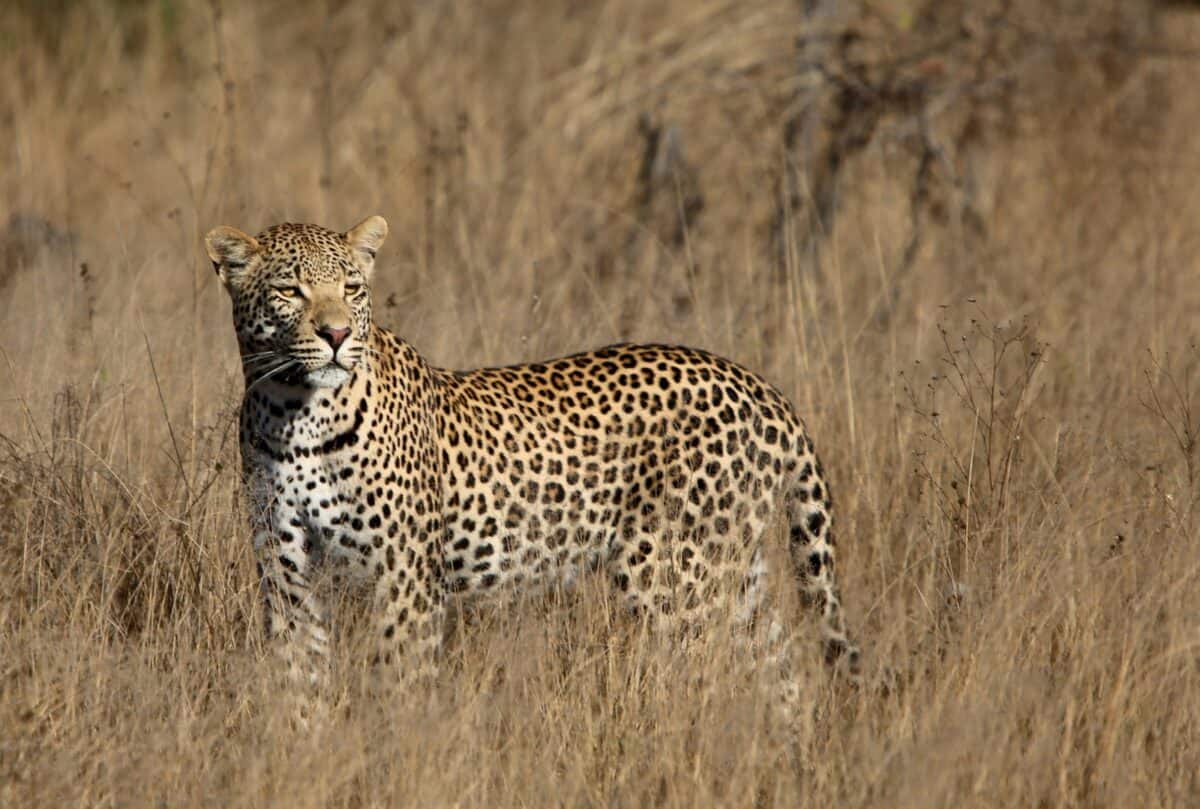

Competition with Other Predators

Cheetahs occupy a precarious position in the predator hierarchy. Despite their impressive speed, they lack the strength and power of lions, leopards, and hyenas. In intact ecosystems with sufficient space and prey, these predators coexist through niche partitioning and temporal separation. However, as habitats shrink and prey becomes scarcer, interspecific competition intensifies. Lions and hyenas frequently steal cheetah kills—a phenomenon called kleptoparasitism—forcing cheetahs to hunt more frequently and expend additional energy. Studies in the Serengeti documented that cheetahs lose up to 12% of their kills to larger predators.

More concerning is direct predation on cheetahs, particularly cubs. Lions may kill adult cheetahs and cubs opportunistically, not for food but to eliminate competition. In the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, researchers found that up to 57% of cheetah cub mortality was attributed to predation by other carnivores. As protected areas become increasingly isolated islands of habitat, predator densities within them can become artificially high, intensifying these competitive pressures. This dynamic creates a conservation conundrum where successfully protecting all large carnivores in the same restricted area may inadvertently disadvantage cheetahs, the least competitive of the group.

Disease Transmission

The cheetah’s compromised immune system, a consequence of their genetic bottleneck, makes them particularly susceptible to diseases. In both wild and captive settings, cheetahs have shown high vulnerability to infectious diseases that might cause minimal harm to other felids. Feline infectious peritonitis (FIP), canine distemper virus (CDV), and anthrax have all caused significant mortality events in cheetah populations. A single disease outbreak can devastate a small, isolated population, as demonstrated in 1994 when CDV killed approximately 30% of the cheetahs in the Serengeti.

The risk is compounded by increasing contact with domestic animals as human settlements expand into cheetah habitat. Domestic dogs can transmit rabies and distemper, while domestic cats can spread feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) and feline leukemia virus (FeLV). Additionally, livestock may carry diseases like bovine tuberculosis that can affect cheetahs. Climate change may further alter disease dynamics by changing vector distributions and creating environmental conditions favorable to certain pathogens. With their limited genetic diversity providing little resilience against novel pathogens, disease represents a potentially catastrophic threat that could rapidly accelerate population declines even in otherwise protected areas.

Trophy Hunting and Poaching

While not targeted for traditional medicine like tigers or rhinos, cheetahs still face pressure from hunting activities. Historically, trophy hunting removed significant numbers of cheetahs, particularly in southern Africa. Though most countries now restrict or ban cheetah hunting, illegal poaching continues in some regions. Additionally, cheetahs are often caught in snares set for other species—a form of unintentional poaching that nevertheless reduces populations. These wire snares, typically set to catch antelopes for bushmeat, don’t discriminate and can cause painful deaths or debilitating injuries to cheetahs.

Particularly concerning is the selective removal of prime breeding adults through trophy hunting in the past, which has had long-term genetic consequences for surviving populations. Though direct hunting of cheetahs has decreased, the legacy of selective removal of the largest, healthiest individuals continues to affect population viability today. Furthermore, in some regions, cheetahs are still killed for their skins, which are used in traditional ceremonies or sold as luxury items. While international trade in cheetah parts is banned under CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species), enforcement challenges and black market demand continue to drive this threat in certain areas.

Inadequate Protected Areas

Protected areas form the backbone of cheetah conservation efforts, yet they frequently fall short of providing adequate security for these wide-ranging predators. Research indicates that between 70-80% of cheetahs in countries like Namibia, Botswana, and Kenya live outside formally protected areas, on private or communal lands with minimal legal protection. Even large national parks rarely encompass the entire home range of a cheetah population, leaving them vulnerable when they inevitably cross boundaries into unprotected areas.

Furthermore, many protected areas face challenges in effective enforcement due to funding shortfalls, insufficient staff, equipment limitations, and in some cases, corruption. A 2018 assessment found that more than half of Africa’s protected areas were suffering from serious deficiencies in basic protection capabilities. The situation is particularly dire in countries experiencing political instability or armed conflict, where conservation infrastructure has collapsed entirely in some regions. Without addressing these systemic weaknesses in the protected area network and developing innovative approaches to protect cheetahs outside formal reserves, even the most ambitious conservation initiatives will struggle to reverse population declines.

The Path Forward: Conservation Actions Making a Difference

Despite the daunting challenges facing cheetah populations, innovative conservation approaches are showing promising results across their range. Community-based conservation programs, particularly in countries like Namibia, have transformed farmers from adversaries into allies by employing local people as conservation guards, developing ecotourism opportunities that provide economic benefits, and implementing livestock management techniques that reduce predation. The Cheetah Conservation Fund’s Livestock Guarding Dog program, which provides specially trained dogs to farmers, has reduced livestock losses by over 80% in participating communities, dramatically decreasing retaliatory killings of cheetahs.

Habitat corridors represent another crucial strategy, with initiatives like the KAZA Transfrontier Conservation Area creating protected pathways between isolated populations across five southern African countries. Meanwhile, advances in genetic science offer hope for addressing inbreeding concerns, with researchers developing assisted reproduction techniques and genetic mapping to guide population management. Educational outreach has helped reduce demand for exotic pets, while improved law enforcement has disrupted trafficking networks. The cheetah’s future remains uncertain, but these successful interventions demonstrate that with adequate resources, political will, and community engagement, the decline can be reversed. The race to save the world’s fastest land animal continues—and with coordinated global action, cheetahs may yet outrun extinction.

- 12 US States Where Wolves Are Making a Comeback - August 13, 2025

- 10 Most Dangerous Hiking Trails in the US - August 13, 2025

- 12 Creatures That Glow in the Dark and Why It Helps Them Survive - August 13, 2025