In the intricate tapestry of forest ecosystems, bears stand as silent yet powerful guardians of environmental health. These magnificent mammals, often portrayed as fearsome predators, actually serve as ecological engineers that help maintain and enhance forest biodiversity. From their seed-dispersing habits to their nutrient cycling activities, bears play multifaceted roles that extend far beyond their reputation as apex predators. Understanding how these large omnivores contribute to forest health illuminates the complex interconnections within natural systems and highlights the importance of conserving bear populations worldwide. This article explores the various ways bears function as keystone species in maintaining vibrant, productive forest ecosystems across the globe.

Seed Dispersal: Bears as Forest Gardeners

Bears serve as some of nature’s most effective seed dispersers, earning them the nickname “forest gardeners.” As omnivores with diverse diets, bears consume enormous quantities of berries, fruits, and nuts during their active seasons. A single brown bear can eat thousands of berries in a day during peak foraging periods. This voracious appetite for fruit results in the consumption of millions of seeds that pass through their digestive systems and are deposited across wide areas of the forest floor.

Research has shown that seeds that pass through a bear’s digestive tract often have enhanced germination rates compared to undispersed seeds. The digestive process helps break down the seed coat, while the natural fertilizer that accompanies the deposited seeds provides an excellent starting environment for new plants. Studies in North America have demonstrated that bears can disperse seeds up to several kilometers from the parent plant, helping forest plants colonize new areas and maintaining genetic diversity within plant populations. This long-distance dispersal is particularly crucial for forest resilience and adaptation in the face of climate change.

Nutrient Cycling: Bears as Ecosystem Engineers

Bears contribute significantly to nutrient cycling within forest ecosystems, acting as natural conduits that transport nutrients between different parts of the environment. When bears catch and consume salmon during spawning runs, they carry these fish into the forest, sometimes hundreds of meters from streams. As they consume parts of the fish and leave carcass remains on the forest floor, they effectively transfer marine-derived nutrients, particularly nitrogen and phosphorus, into terrestrial ecosystems.

Scientists have tracked this nutrient transfer by measuring nitrogen isotopes in trees near salmon streams where bears are active. Trees in these areas often grow at three times the rate of those in comparable forests without bear-salmon interactions. This “fertilization effect” cascades through the ecosystem, enhancing soil fertility and supporting more abundant and diverse plant communities. In coastal forests of the Pacific Northwest, researchers have estimated that bears deposit approximately 20% of the total nitrogen budget in riparian zones, demonstrating their crucial role in ecosystem enrichment.

Forest Thinning and Vegetation Management

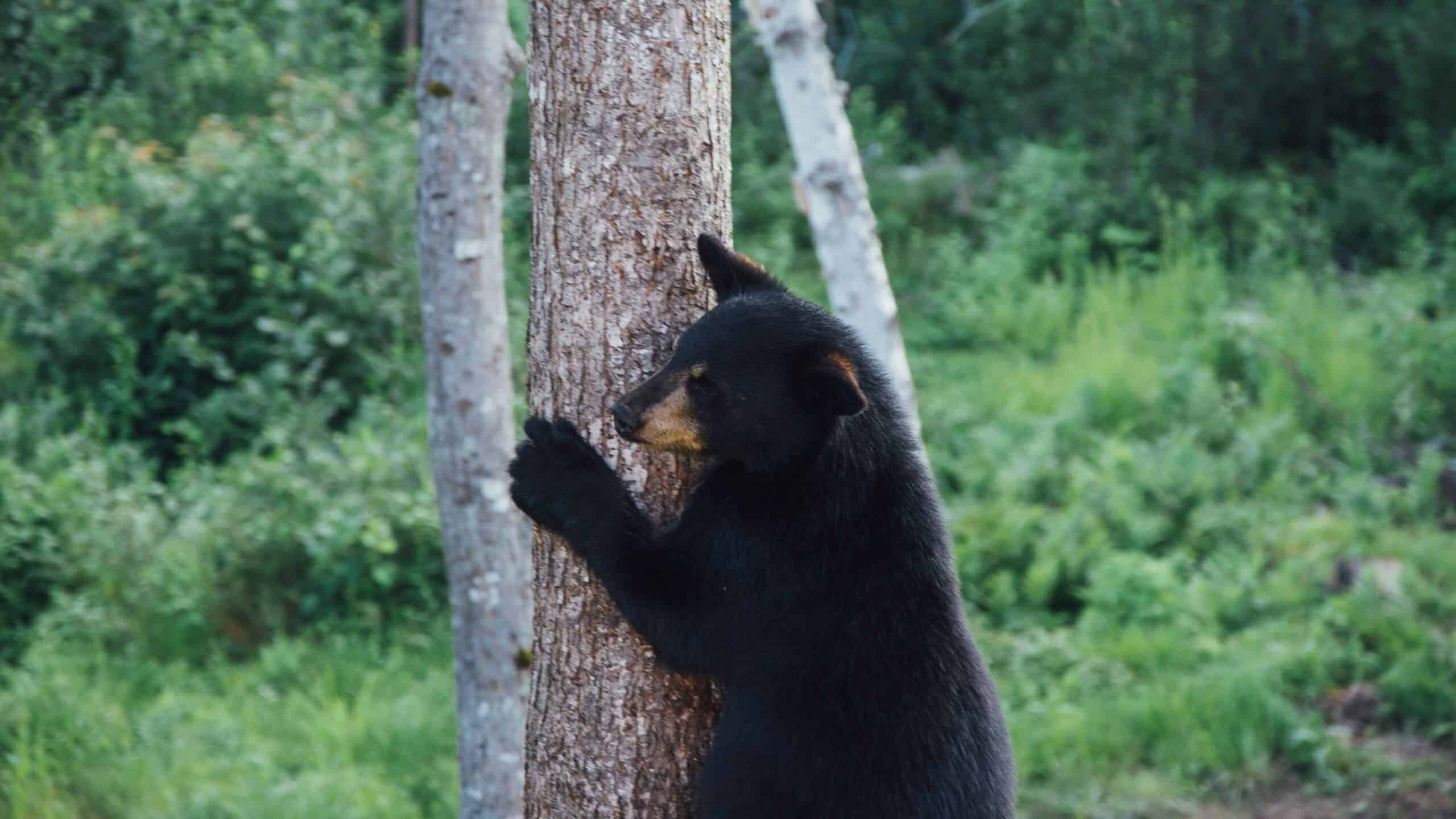

While foraging for food, bears inadvertently help manage forest vegetation in ways that promote diversity and resilience. Their habit of breaking branches while climbing trees to reach fruits and nuts creates small canopy gaps that allow sunlight to reach the forest floor, promoting understory growth. Additionally, bears often strip bark from trees while searching for insects or sap, which can create wildlife habitat features such as cavities that benefit numerous other species.

Bears’ digging activities while searching for roots, bulbs, and insect larvae aerate the soil and create microsites that favor certain plant species. In some forest types, research has shown that areas with regular bear disturbance host up to 30% higher plant diversity compared to undisturbed areas. These activities essentially mimic the effects of small-scale natural disturbances that many forest ecosystems depend on for maintaining biodiversity and productivity, making bears important agents in forest succession processes.

Carrion Processing and Scavenger Support

As both predators and scavengers, bears play a vital role in processing carrion and supporting diverse scavenger communities within forest ecosystems. When bears feed on large animal carcasses, they typically consume the most nutritious parts first and then leave substantial remains for other scavengers. This behavior creates a cascading effect that supports numerous other species, from ravens and eagles to smaller mammals and invertebrates that specialize in decomposition.

The partial consumption pattern exhibited by bears is particularly beneficial for ecosystem health, as it extends the availability of carrion resources over time and space. Research in Yellowstone National Park has documented over 50 different species benefiting from bear-killed elk carcasses. Additionally, by quickly consuming carrion, bears help reduce the persistence of diseases that might otherwise spread through wildlife populations. Their role in this “cleanup crew” function helps maintain healthier wildlife communities throughout forest ecosystems.

Creation of Forest Gaps and Early Successional Habitat

Bears contribute to forest structural diversity through their feeding habits and physical interactions with vegetation. When black bears and grizzlies forage in dense forest stands, they often create small clearings by breaking down vegetation and exposing mineral soil. These disturbances create early successional habitat patches within mature forests that provide critical resources for many wildlife species. In particular, the berries and other soft mast that grow abundantly in these openings support diverse animal communities.

Studies in the Appalachian Mountains have shown that areas where bears have created natural gaps host significantly higher numbers of pollinators, songbirds, and small mammals compared to undisturbed forest. This “mosaic effect” increases overall biodiversity at the landscape scale. Bears essentially perform a service similar to controlled burns or selective logging in creating habitat heterogeneity, but they do so in a natural pattern that has co-evolved with forest systems over millennia, making their disturbance regime particularly beneficial for native species.

Predator-Prey Dynamics and Trophic Cascades

As apex predators in many forest ecosystems, bears influence the behavior and population dynamics of their prey species, triggering what ecologists call “trophic cascades.” When bears prey on ungulates like deer, elk, and moose, they can prevent overgrazing of certain plant species and allow for more diverse vegetation communities. In areas where bears actively hunt ungulate calves, studies have documented reduced browsing pressure on tree seedlings and saplings, resulting in improved forest regeneration.

The mere presence of bears also creates a “landscape of fear” that alters herbivore behavior. Deer and elk tend to avoid areas with high bear activity or move through them more quickly, creating spatial variation in grazing pressure across the landscape. Research in Yellowstone has shown that the reintroduction of grizzly bears, along with wolves, has allowed aspen, willow, and cottonwood to recover in riparian areas by changing elk behavior. These vegetation improvements have subsequently benefited beaver populations and improved stream health, demonstrating how bear-driven trophic cascades can enhance entire ecosystems.

Soil Disturbance and Microhabitat Creation

Bears are prolific diggers, and their soil disturbance activities create valuable microhabitats throughout forest ecosystems. When searching for insect larvae, small mammals, or edible roots, bears can excavate substantial areas, turning over soil and exposing mineral layers. These disturbances create specialized niches for pioneer plant species that require bare soil for germination and establishment. Studies in boreal forests have found that bear diggings host unique assemblages of plants that increase overall forest biodiversity.

The depressions created by bear digging also capture moisture and organic matter, forming small wetland-like microhabitats in otherwise dry forest environments. These “bear pits” can persist for several years and support amphibian breeding, invertebrate communities, and moisture-loving plants. In Alaska, researchers have documented that areas with abundant bear digging activity can host up to 25% more plant species than undisturbed areas within the same forest type, highlighting the bear’s role as a creator of environmental heterogeneity.

Regulation of Pest Species Populations

Bears provide valuable ecosystem services by regulating populations of potential pest species in forest environments. Both black bears and grizzlies consume large quantities of insects, particularly ants, wasps, and beetle larvae. In some regions, bears are significant predators of mountain pine beetle larvae, which have caused devastating forest die-offs across North America. By tearing open infected trees and consuming the larvae, bears may help slow the spread of these destructive forest pests.

Bears also prey on rodents that can damage tree roots or consume excessive amounts of seeds and seedlings. In years with high rodent populations, bears may shift their foraging behavior to target these abundant prey, helping prevent population explosions that could damage forest regeneration. Research in European forests has suggested that areas with healthy bear populations experience fewer rodent-related forest damage events compared to areas where bears have been extirpated, though more studies are needed to fully quantify this effect.

Trail Creation and Forest Connectivity

Bears are creatures of habit that create and maintain trail networks throughout their forest territories. These well-worn paths follow efficient routes between key resources such as feeding areas, water sources, and den sites. Bear trails often become used by numerous other wildlife species, creating important movement corridors through dense vegetation. Research using camera traps has documented over 20 different mammal species regularly using bear-created trails in temperate forests.

These natural pathways enhance forest connectivity by facilitating animal movement and gene flow across the landscape. They are particularly important in fragmented habitats where natural corridors between forest patches are limited. Bear trails also influence seed dispersal patterns, as seeds dropped by other animals tend to concentrate along these movement routes. In some cases, distinctive plant communities develop along heavily used bear trails due to this concentrated seed deposition and the disturbance created by regular animal traffic, further enhancing forest diversity patterns.

Adaptation of Plant Species to Bear Foraging

Over evolutionary time, many forest plant species have adapted to bear foraging in ways that enhance both plant survival and bear nutrition. Numerous berry-producing plants in bear habitat produce fruits with specific characteristics—high sugar content, conspicuous colors, and tough seeds—that attract bears while ensuring successful seed dispersal. The timing of fruit ripening in many forest plants coincides with bears’ need to build fat reserves before hibernation, creating a mutualistic relationship that benefits both parties.

Some plant species show even more specialized adaptations to bear consumption. Certain berry-producing shrubs have evolved physical structures that make their fruits accessible to bears but difficult for smaller animals to harvest completely. Others produce mast crops (nuts and hard fruits) in synchrony across large areas, a strategy called “masting” that helps ensure some seeds escape consumption. These plant adaptations highlight the long coevolutionary history between bears and forest vegetation communities, demonstrating how deeply intertwined bears are with forest ecosystem processes.

Conservation Implications for Forest Management

Understanding bears’ roles in maintaining forest health has important implications for conservation and forest management. In areas where bear populations have declined or been extirpated, forests may experience cascading ecological effects including reduced seed dispersal, altered nutrient cycling, and changes in plant community composition. Forest managers are increasingly recognizing the need to consider bears’ ecological functions when developing conservation strategies. In some regions, “bear-aware” forestry practices aim to maintain habitat features that support bear populations while allowing for sustainable timber harvest.

Protected areas designed to conserve bear populations often provide umbrella protection for entire forest ecosystems and their processes. Research has demonstrated that forests with intact bear populations tend to show greater resilience to climate change and other stressors compared to those without large omnivores. As climate change intensifies, bears’ roles in maintaining diverse, adaptable forest systems may become even more crucial. This recognition is driving increased interest in bear reintroduction programs in regions where they have been lost, with the dual goals of restoring both the species and its ecological functions.

Bears stand as remarkable examples of keystone species whose influence on forest ecosystems extends far beyond their immediate presence. Through seed dispersal, nutrient cycling, vegetation management, and numerous other ecological processes, bears help maintain the health, diversity, and resilience of forest communities across the Northern Hemisphere. Their multifaceted roles touch virtually every aspect of forest function, from soil development to plant community composition to wildlife habitat creation. As we continue to study these magnificent animals, we gain deeper appreciation for the complex ways in which large omnivores support forest health. Conservation efforts that protect bears and their habitat ultimately preserve entire ecological networks, highlighting the interconnectedness of all life within forest ecosystems and the irreplaceable role that bears play as architects of forest health.

- This Great White Shark’s Attack Strategy Will Leave You Stunned - August 24, 2025

- The Weirdest Animal Superpowers That Actually Exist - August 24, 2025

- Wildlife Encounters You Might Have on a Spring Hike - August 23, 2025