Tigers have captivated human imagination for centuries, appearing in folklore, literature, and popular culture across the globe. As the largest living cats and apex predators, tigers naturally inspire awe and fascination. However, this prominence has also led to numerous misconceptions about these magnificent creatures. From exaggerated behaviors to misunderstood physical characteristics, many myths about tigers persist despite scientific evidence to the contrary. In this article, we’ll examine ten common misconceptions about tigers and present the scientific facts that debunk these myths, as provided by wildlife biologists, conservationists, and tiger experts who have dedicated their careers to studying these endangered big cats.

Myth 11 Tigers Roar Before Attacking Their Prey

One of the most widespread myths about tigers is that they roar loudly before pouncing on their prey. This dramatic image has been reinforced by countless movies and television shows, where tigers are depicted announcing their presence with a thunderous roar before charging. However, experts confirm this behavior would be completely counterproductive to a tiger’s hunting success.

In reality, tigers are ambush predators that rely heavily on stealth and surprise. Dr. John Goodrich, Chief Scientist at Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization, explains: “Tigers are incredibly silent hunters. They stalk their prey carefully, moving without making a sound, and attack without warning. A tiger that roared before attacking would quickly become a very hungry tiger, as all potential prey would flee immediately.” Tigers can roar—and their vocalizations can be heard up to 2 miles away—but they typically roar for communication with other tigers, particularly during mating season or to establish territorial boundaries, not while hunting.

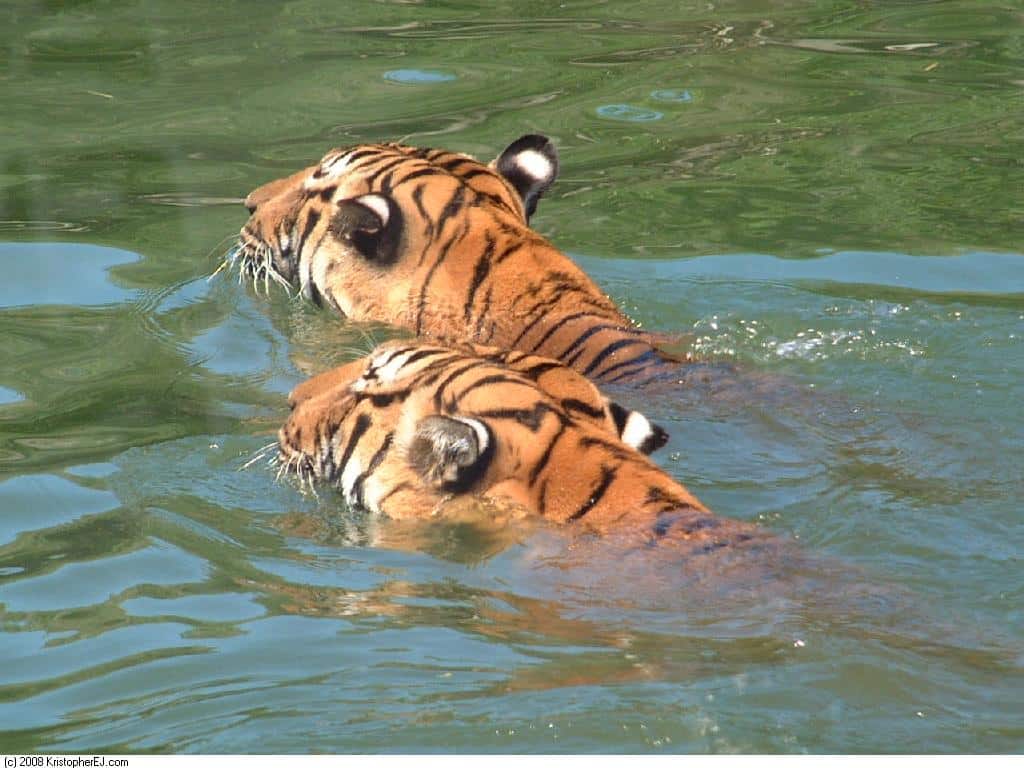

Myth 10 All Tigers Love Water and Are Excellent Swimmers

While many nature documentaries and wildlife shows portray tigers happily splashing in rivers and lakes, the blanket statement that “all tigers love water” is an oversimplification. It’s true that tigers, unlike many domestic cats, don’t generally avoid water and are capable swimmers when needed. However, tiger behavior toward water varies significantly between individuals and subspecies, with some showing a much stronger affinity for aquatic environments than others.

Dr. K. Ullas Karanth, Director for Science-Asia at the Wildlife Conservation Society, notes: “Bengal tigers in the Sundarbans mangrove forests have adapted to a semi-aquatic lifestyle and regularly swim between islands. However, tigers in other habitats may only enter water when necessary for crossing rivers or cooling down in extreme heat.” Tigers’ swimming ability evolved as a survival adaptation rather than as a recreational preference. The notion that all tigers universally “love” water anthropomorphizes these animals and fails to recognize the diversity of behaviors among individuals and populations across different habitats.

Myth 9 Tigers Can Be Domesticated Like House Cats

Some people mistakenly believe that tigers can be domesticated and kept as exotic pets if raised from cubhood. This dangerous misconception has led to tragic incidents involving privately owned tigers. Despite appearances in social media of “tame” tigers interacting with humans, wildlife biologists emphasize that tigers remain wild animals regardless of their upbringing. Domestication is a process that occurs over many generations of selective breeding, not within a single animal’s lifetime.

Dr. Elizabeth Hadly, Professor of Biology at Stanford University, explains: “Tigers are not and cannot be domesticated. What people see as ‘tame’ behavior is usually fear, sedation, or temporary compliance that can change instantly. Even tigers raised from birth by humans retain their wild instincts and can become unpredictable and dangerous, especially as they mature.” The genetic makeup that has evolved over millions of years to make tigers successful predators cannot be erased through human handling. Conservation organizations strongly oppose private ownership of tigers, which not only endangers people but also contributes to the illegal wildlife trade and undermines conservation efforts for these endangered species.

Myth 8 White Tigers Are a Separate Species or Subspecies

White tigers often appear in zoos and entertainment venues, leading many people to believe they represent a distinct species or subspecies of tiger. This is completely false. White tigers are not a separate species, subspecies, or even a naturally occurring variant in the wild. They are Bengal tigers (occasionally Bengal-Siberian hybrids in captivity) with a rare genetic mutation that causes leucism, a condition that reduces the normal pigmentation in the skin and fur.

Dr. Ron Tilson, former coordinator of the Tiger Species Survival Plan, clarified: “White tigers are the result of a genetic anomaly that occurs when two tigers carrying a recessive gene for white coloration mate. In the wild, this mutation is extremely rare and likely disadvantageous, as the white coloration would make it difficult for tigers to camouflage themselves while hunting.” The prevalence of white tigers in captivity is the result of deliberate inbreeding of related tigers to produce this unusual coloration, a practice condemned by legitimate conservation organizations. This inbreeding has led to numerous health problems in white tigers, including skeletal deformities, immune deficiencies, and neurological issues.

Myth 7 Tigers Hunt and Kill Humans Whenever Possible

The myth that tigers are bloodthirsty man-eaters that actively seek out human prey has persisted for centuries, fueled by sensationalized stories and historical accounts of man-eating tigers. While it’s true that some tigers have become man-eaters—most famously the Champawat Tiger, which allegedly killed 436 people in Nepal and India before being shot in 1907—these cases are extremely rare exceptions rather than the rule. In reality, tigers typically avoid humans whenever possible.

Dr. Ullas Karanth explains: “Tigers naturally fear humans and will go out of their way to avoid contact. Man-eating behavior typically develops only when tigers are unable to hunt their natural prey, usually due to injury, age, or habitat degradation that has depleted natural prey species.” Studies show that even in areas where tigers and humans live in close proximity, attacks are remarkably uncommon considering the potential for interaction. Most tiger attacks on humans occur when people enter tiger territory unexpectedly, when tigers are defending cubs, or in rare cases where individual tigers have learned to associate humans with food through improper wildlife management practices.

Myth 6 Tigers Are Solitary Animals That Never Socialize

Tigers have long been characterized as completely solitary animals that only come together to mate. While tigers do spend much of their time alone and don’t form permanent social groups like lions, recent research using camera traps and GPS collars has revealed that tiger social behavior is more complex than previously thought. Tigers do interact with each other outside of mating, particularly in areas with abundant prey.

Dr. Joseph Smith, tiger researcher at Panthera, notes: “We’ve documented male tigers sharing kills with females and cubs, adult siblings maintaining territories adjacent to each other, and even unrelated tigers tolerating each other at kill sites when food is plentiful.” Female tigers also maintain strong bonds with their cubs for up to two years, teaching them hunting skills and territorial awareness. Rather than being antisocial, tigers have flexible social systems that adapt to ecological conditions. They maintain awareness of other tigers in their vicinity through scent marking and vocalizations, creating a social network despite not living in groups. This nuanced understanding of tiger sociality represents an important correction to the oversimplified “completely solitary” myth.

Myth 5 Tigers Always Kill Their Prey by Breaking the Neck

A common misconception is that tigers always kill their prey by delivering a precise bite to break the neck vertebrae. While this makes for dramatic storytelling, it’s not how tigers typically hunt. According to wildlife biologists who have studied thousands of tiger kills, the primary killing method used by tigers is suffocation through a throat bite that crushes the windpipe or severs major blood vessels, not breaking the neck.

Dr. George Schaller, renowned field biologist and author of “The Deer and the Tiger,” explains: “Tigers generally kill large prey by grabbing the throat and holding on until the animal suffocates. With smaller prey, they may deliver a bite to the back of the neck that damages the spinal cord, but the classic ‘neck snap’ is largely mythological.” The confusion may stem from observations of tigers dragging dead prey, which can cause the head to hang at an angle that appears as though the neck is broken. Tigers have evolved incredibly powerful jaws and sharp canine teeth that are perfectly adapted for their actual killing technique—a precision bite to the throat that quickly subdues prey while minimizing the tiger’s risk of injury during the hunt.

Myth 4 Tigers Cannot Climb Trees

Many people believe that tigers, unlike leopards and jaguars, are unable to climb trees due to their size and weight. This myth likely originated from comparisons with leopards, which are famously adept at hauling prey into trees to protect it from other predators. However, wildlife biologists and field researchers have documented numerous instances of tigers climbing trees, particularly younger tigers and those living in areas where climbing provides a specific advantage.

Dr. Dale Miquelle, Tiger Program Coordinator for the Wildlife Conservation Society, clarifies: “While tigers don’t routinely climb trees like leopards do, they are certainly capable climbers when motivated. Young tigers often climb as part of play behavior, and adults may climb to escape floods, cool off on hot days, or occasionally to hunt arboreal prey.” Their climbing ability is somewhat limited by their size and weight, especially for larger male tigers that can weigh over 500 pounds. Tigers generally prefer to stay on the ground where their strength and speed give them advantages in hunting, but the blanket statement that they “cannot climb trees” is demonstrably false based on field observations throughout their range.

Myth 3 Tiger Parts Have Medicinal Properties

One of the most destructive myths about tigers is the belief that their body parts—particularly bones, claws, and whiskers—possess special healing properties or medicinal value. This misconception has fueled poaching and illegal wildlife trafficking that continues to threaten tiger populations across Asia. Despite centuries of use in traditional medicine systems, there is absolutely no scientific evidence supporting any medicinal benefits from tiger parts.

Dr. Barney Long, Director of Species Conservation at Global Wildlife Conservation, states: “The supposed medicinal properties of tiger parts have been thoroughly debunked by modern science. Tiger bone, for example, contains calcium and protein just like the bones of any other mammal—nothing unique or medicinally valuable.” The continued demand for tiger parts is based entirely on cultural beliefs and superstitions rather than evidence. Conservation organizations work with traditional medicine practitioners to promote scientifically-validated alternatives and educate communities about the ecological importance of tigers. The illegal trade in tiger parts not only threatens tiger populations but also diverts people from seeking proven medical treatments, potentially endangering human health as well.

Myth 2 All Tigers Have Identical Stripe Patterns

Many people believe that tiger stripes follow a standard pattern, with all tigers having essentially the same striping. This misconception may stem from stylized depictions in art and media that present tiger stripes as uniform. In reality, tiger stripes are as unique as human fingerprints—no two tigers have identical patterns, a fact that allows researchers to identify individual tigers in the wild through camera trap photographs.

Dr. Melvin Sunquist, Professor Emeritus at the University of Florida and tiger expert, explains: “Each tiger has a completely unique stripe pattern that develops in utero. These patterns remain consistent throughout the tiger’s life and extend not just to the fur but even to the skin beneath—if a tiger were shaved, you would still see the pattern.” The distinctiveness of stripe patterns varies by subspecies as well. Sumatran tigers typically have thinner, more densely packed stripes, while Siberian (Amur) tigers often have fewer, wider stripes with more reddish-brown fur. These unique markings serve as natural camouflage in different habitats, breaking up the tiger’s outline in tall grass and dappled forest light, and have become an invaluable tool for conservation scientists monitoring wild tiger populations.

Myth 1 Tiger Populations Are Recovering Globally

A dangerous misconception that has gained traction in recent years is that tiger populations are rebounding strongly across their range. While there have been some localized success stories in tiger conservation, particularly in India, Nepal, and Russia, the global situation remains precarious. Tigers now occupy less than 7% of their historical range, and three subspecies (Bali, Javan, and Caspian tigers) have gone extinct in the past century. Of the estimated 3,726-5,578 tigers remaining in the wild, more than half are found in India.

Dr. John Goodrich of Panthera explains: “While some populations are stable or increasing slightly, tigers continue to face severe threats from poaching, habitat loss, and human-wildlife conflict. Recent reports of ‘increasing tiger numbers’ must be interpreted cautiously, as some reflect improved counting methods rather than actual population growth.” In countries like Malaysia, Myanmar, and Laos, tiger populations have collapsed to near-extinction levels in recent decades. Conservation experts emphasize that complacency about tiger recovery is premature and potentially harmful to ongoing protection efforts. Without continued vigilance and expanded conservation initiatives, particularly in Southeast Asia, the long-term survival of wild tigers remains far from guaranteed.

Conclusion: Understanding Tigers Beyond the Myths

Separating fact from fiction is crucial for tiger conservation and for developing a genuine appreciation of these magnificent animals. The persistence of myths not only distorts public understanding but can directly harm tiger populations through misguided policies, dangerous human behaviors, or support for practices like private ownership that undermine conservation. By examining these misconceptions through a scientific lens, we gain a more accurate and nuanced understanding of tiger biology, behavior, and conservation needs. The reality of tigers—their complex social behaviors, remarkable adaptations, and precarious conservation status—is far more fascinating than the myths that have surrounded them for centuries. As we work to ensure tigers survive for future generations, let us base our actions on scientific facts rather than persistent but inaccurate beliefs. The future of these magnificent big cats depends on our commitment to understanding them as they truly are, not as mythology has portrayed them.

- 8 Times Animals Helped Solve Crimes in the Most Unexpected Ways - August 20, 2025

- 10 Stunning Animals You Can See in the Great Barrier Reef - August 20, 2025

- 14 Loudest Birds in the U.S. - August 20, 2025