Throughout America’s rich history, certain animals have come to represent the nation’s values, struggles, and triumphs. These creatures have been woven into the fabric of American identity, appearing in everything from government seals to wartime propaganda. More than mere mascots, these patriotic animals embody qualities Americans have long admired: strength, independence, vigilance, and freedom. Their stories reflect the nation’s journey from colonial outpost to global superpower.

The symbolic connection between these animals and American patriotism goes beyond simple representation. Many have played vital roles in actual historical events, served alongside soldiers in combat, or helped shape how Americans view their national character. From the halls of Congress to remote battlefields, these creatures have left their mark on the American story. The following ten animals have earned special places in the pantheon of American patriotic symbols.

The Bald Eagle America’s Enduring National Symbol

No animal is more closely associated with American patriotism than the bald eagle. Selected as the national emblem in 1782, this majestic raptor appears on the Great Seal of the United States, the presidential seal, and countless government documents. Benjamin Franklin famously objected to the choice, preferring the wild turkey as more representative of American virtues, but the eagle’s powerful appearance and soaring flight prevailed. With its piercing gaze and seven-foot wingspan, the bald eagle projects the strength and freedom the young nation aspired to embody.

The bald eagle’s journey mirrors America’s environmental conscience. Once abundant throughout North America, by the 1960s, hunting, habitat destruction, and DDT poisoning had reduced the population to just 417 nesting pairs in the continental United States. Protected by landmark legislation including the 1940 Bald Eagle Protection Act and later the Endangered Species Act, the eagle made a remarkable recovery. In 2007, it was removed from the endangered species list, with populations now exceeding 9,700 breeding pairs—a conservation success story that parallels America’s growing environmental awareness.

The American Buffalo Symbol of the Frontier Spirit

The American buffalo (more accurately termed the American bison) represents both the abundance of the American frontier and one of the nation’s greatest ecological tragedies. Once numbering in the tens of millions, these massive mammals thundered across the Great Plains, serving as the economic and spiritual foundation for many Native American tribes. The buffalo appears on numerous state flags, the Buffalo nickel (minted 1913-1938), and as the official mammal of the United States since 2016, when President Obama signed the National Bison Legacy Act.

The near-extinction of the buffalo in the late 19th century—when populations fell to fewer than 1,000 animals—represents a dark chapter in American history. The systematic slaughter was tied to both commercial interests and government policy aimed at subjugating Native peoples by eliminating their primary resource. The 20th century saw dedicated conservation efforts by figures like Theodore Roosevelt lead to a remarkable recovery. Today, with approximately 500,000 bison in North America, the buffalo stands as a symbol of both American resilience and the importance of conservation stewardship.

Sergeant Stubby America’s Most Decorated War Dog

Perhaps no animal embodied American military courage more than Sergeant Stubby, a stray Boston terrier mix who became the most decorated war dog of World War I. Found wandering the Yale University campus in 1917, Stubby was smuggled to France by Private J. Robert Conroy of the 102nd Infantry Regiment. Far from being merely a mascot, Stubby participated in 17 battles over 18 months, warning troops of incoming artillery shells, locating wounded soldiers in no man’s land, and even capturing a German spy by biting and holding the infiltrator until American soldiers arrived.

Stubby’s battlefield heroics earned him the rank of Sergeant and numerous medals, including the Purple Heart. After the war, he met three presidents, led parades, and became a lifetime member of the American Legion and the YMCA. When he died in 1926, his preserved remains were presented to the Smithsonian Institution, where they remain on display. Sergeant Stubby’s remarkable story illustrates the special bond between soldiers and animals during wartime and stands as a testament to extraordinary courage regardless of species.

The Wild Mustang Symbol of Western Freedom

Few animals capture the untamed spirit of the American West like the wild mustang. Descendants of horses brought by Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century, these resilient equines adapted to the harsh conditions of the American frontier. As the nation expanded westward, mustangs became essential partners to Native Americans, pioneers, cowboys, and cavalry soldiers. Their image gallops through American art, literature, and film as the embodiment of freedom and independence—values Americans have cherished since the nation’s founding.

The Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act of 1971 recognized mustangs as “living symbols of the historic and pioneer spirit of the West.” Today, approximately 86,000 wild horses roam public lands, protected yet controversial as land managers balance their preservation with environmental impact concerns. Organizations like the Mustang Heritage Foundation work to ensure these iconic animals remain part of America’s living heritage, promoting adoption programs and gentling techniques. The mustang’s ongoing story reflects America’s complex relationship with its frontier past and the challenges of preserving historical symbols in a changing landscape.

Old Abe The Civil War Eagle

During America’s bloodiest conflict, one of the most famous military mascots was a bald eagle named Old Abe, who served with the 8th Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Captured as an eaglet by a Chippewa chief and traded to a Wisconsin farmer in 1861, the eagle was named after President Abraham Lincoln and donated to Company C of the “Eagle Regiment.” Carried on a special perch into battle, Old Abe participated in 42 engagements during the Civil War, including the Vicksburg Campaign and the Battle of Corinth, where he spread his wings and screamed defiantly amid gunfire and artillery barrages.

Confederate troops called Old Abe “that Yankee buzzard” and placed a bounty on his head, recognizing his powerful symbolic value. After the war, Old Abe became a national celebrity, appearing at veterans’ reunions and patriotic events until his death in 1881 from smoke inhalation after a fire in the Wisconsin Capitol. His mounted form was displayed until destroyed in a 1904 fire, but his legacy lives on in Wisconsin’s military history. The 101st Airborne Division later adopted Old Abe as their insignia, nicknamed “Screaming Eagles” in honor of the famous war bird who embodied Northern resolve during America’s greatest trial.

The Wild Turkey Benjamin Franklin’s Preferred National Bird

While the bald eagle secured its place as America’s national bird, Benjamin Franklin famously advocated for the wild turkey instead. In a letter to his daughter, Franklin criticized the eagle as “a Bird of bad moral Character” who “does not get his Living honestly,” while praising the turkey as “a much more respectable Bird, and withal a true original Native of America.” Though Franklin’s preference didn’t prevail, the wild turkey has maintained its patriotic associations, particularly through its connection to Thanksgiving celebrations—a quintessentially American holiday commemorating the cooperation between Pilgrims and Native Americans.

The wild turkey’s American story includes a remarkable conservation comeback. Nearly extirpated from much of its range by the early 20th century due to unregulated hunting and habitat loss, populations have recovered dramatically thanks to scientific wildlife management. Today, approximately 7 million wild turkeys inhabit the United States, with hunting seasons carefully regulated to maintain sustainable populations. The National Wild Turkey Federation, founded in 1973, has helped restore these birds to their historical range, making the wild turkey one of America’s greatest wildlife restoration success stories and a living symbol of effective conservation principles.

Smokey Bear Patriotic Symbol of Conservation

While not a wild animal, Smokey Bear represents one of America’s most successful public service campaigns and embodies the nation’s commitment to preserving natural resources. Created in 1944 by the U.S. Forest Service and the Advertising Council, Smokey’s message “Only YOU Can Prevent Forest Fires” (later updated to “Wildfires”) has educated generations of Americans about conservation responsibility. Smokey’s creation during World War II had patriotic undertones, as authorities feared Japanese incendiary balloon attacks might start forest fires that would divert resources from the war effort.

In 1950, the character gained new resonance when a bear cub was found clinging to a burned tree after a New Mexico wildfire. Named Smokey, the cub was treated for burns and sent to the National Zoo in Washington, D.C., where he lived as a living symbol of fire prevention until 1976. By act of Congress, Smokey Bear’s image is protected by federal law, and his campaign has helped reduce annual burned acreage from 22 million acres in 1944 to an average of 6.7 million today. Smokey’s enduring appeal reflects America’s patriotic commitment to preserving its natural heritage for future generations.

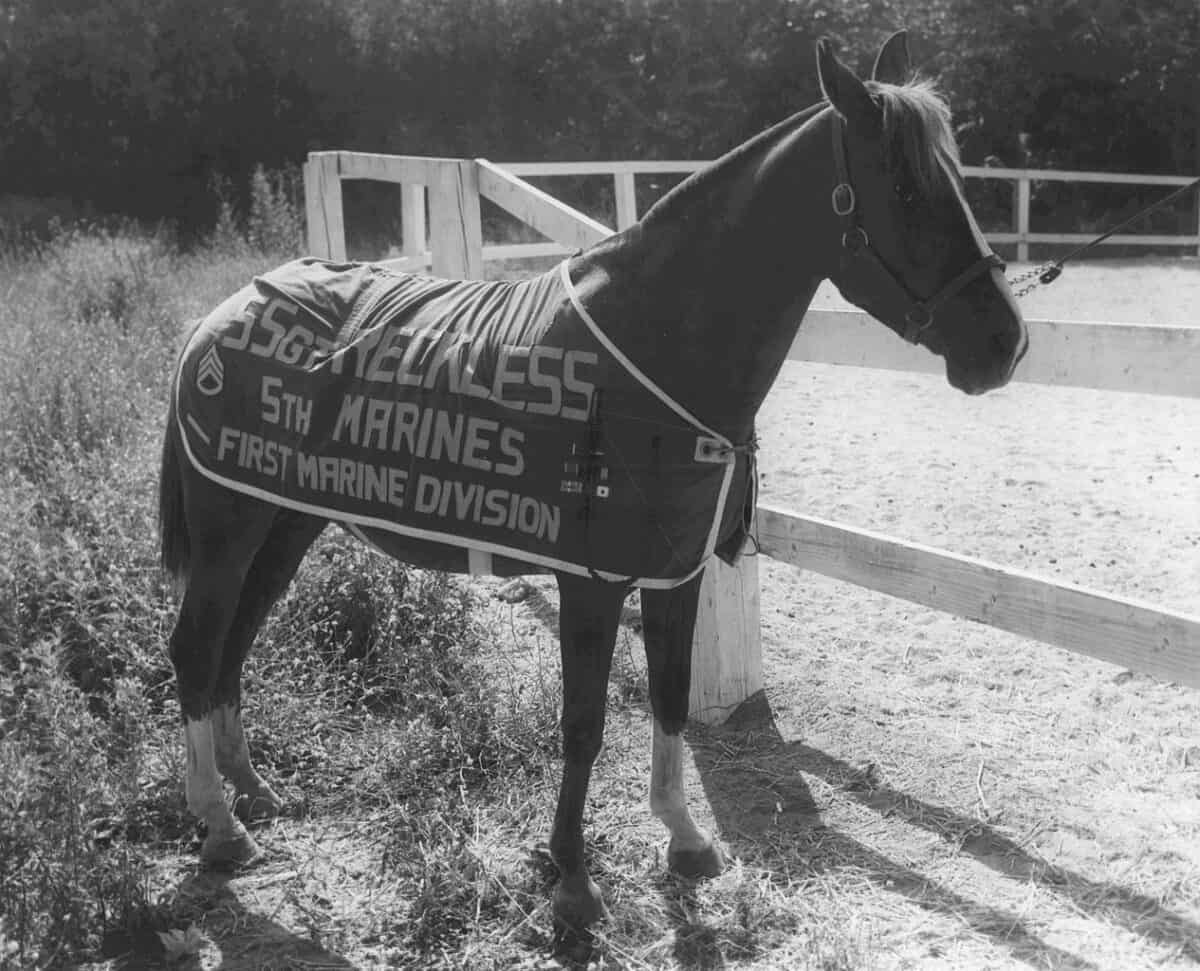

Reckless The Korean War Horse Hero

Staff Sergeant Reckless, a small Mongolian mare, earned her place in military history during the Korean War, serving with the 5th Marine Regiment. Purchased in 1952 from a Korean boy who needed money for his sister’s medical treatment, Reckless was trained to carry ammunition to the front lines and transport wounded soldiers to safety. During the Battle of Outpost Vegas in March 1953, she made 51 solo trips through a battlefield strewn with mines and enemy fire, carrying 386 rounds of ammunition (over 9,000 pounds) up steep hills to gun crews. Wounded twice, she never stopped, even shielding Marines with her body.

Decorated with two Purple Hearts, a Marine Corps Good Conduct Medal, and numerous campaign medals, Reckless was promoted to Staff Sergeant in 1954, a rank never before bestowed on an animal. After the war, she was brought to the United States, where she lived at Camp Pendleton until her death in 1968. In 2013, a bronze statue of Reckless was unveiled at the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Virginia, honoring her extraordinary courage. Her story exemplifies the special bond between American service members and the animals that serve alongside them in defense of freedom.

The American Alligator Symbol of Southern Resilience

The American alligator represents a uniquely Southern contribution to America’s patriotic animal pantheon. Native to the southeastern United States, these ancient reptiles have figured prominently in regional identity since colonial times. During the American Revolution, South Carolina militias often wore silver crescent badges inscribed with the word “Liberty” alongside an image of an alligator, symbolizing fierce defense of homeland. The “Don’t Tread On Me” Gadsden flag, with its rattlesnake warning, reflected similar reptilian symbolism of American resistance to tyranny.

Like many iconic American animals, the alligator faced near-extinction in the mid-20th century due to overhunting and habitat destruction. Protected under the Endangered Species Act in 1973, alligator populations rebounded dramatically through careful management programs that balanced conservation with sustainable use. Today, with over 5 million alligators thriving across the Southeast, they represent one of America’s greatest conservation success stories. The University of Florida’s adoption of the alligator as its mascot in 1911 further cemented this reptile’s place in regional pride, with the “Gator Nation” becoming a powerful expression of Southern identity within the broader American experience.

Balto and Togo The Heroic Sled Dogs of Nome

In the winter of 1925, an epidemic of diphtheria threatened the isolated town of Nome, Alaska. With the only serum hundreds of miles away in Anchorage and conventional transportation impossible due to extreme weather, officials organized a relay of dog sled teams to transport the life-saving medicine. The 674-mile “Great Race of Mercy” through blizzard conditions and temperatures reaching -40°F tested the limits of human and canine endurance. While Balto, who led the final leg into Nome, received most of the initial fame (including a statue in New York’s Central Park), it was Togo who covered the longest and most dangerous stretch—261 miles—demonstrating extraordinary navigation skills through whiteout conditions.

These heroic huskies embodied the American frontier spirit of perseverance against overwhelming odds. Their epic journey saved countless lives and captured the nation’s imagination, receiving front-page coverage across the country. The serum run inspired the annual Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race and has been immortalized in books, films, and exhibitions. Beyond their immediate life-saving mission, Balto and Togo’s story highlighted the vital importance of Alaska’s dog sled teams in connecting remote communities during an era of rapid modernization, preserving an appreciation for traditional knowledge and the special partnership between humans and working animals in American frontier culture.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of America’s Patriotic Animals

The animals that have earned places in America’s patriotic pantheon tell a multifaceted story about the nation itself. From the majestic bald eagle soaring on the Great Seal to the humble war dogs that saved countless American lives on the battlefield, these creatures reflect the values, struggles, and aspirations that have shaped the American experience. Their stories reveal a nation that has sometimes failed in its stewardship of wildlife yet has also demonstrated remarkable commitment to conservation and rehabilitation when confronted with the consequences of exploitation.

These patriotic animals serve as living links to different chapters of American history—from the Revolutionary era to the frontier expansion, through world wars and into the modern conservation movement. Their symbolic power continues to resonate in contemporary American culture, appearing in everything from military insignia to sports team mascots. As the nation evolves, these animal symbols adapt with it, acquiring new layers of meaning while maintaining their connection to foundational American ideals.

Perhaps most importantly, these animals remind Americans that patriotism extends beyond human achievements to encompass responsibility for the natural world. The near-extinction and subsequent recovery of icons like the bald eagle, buffalo, and alligator parallel America’s growing environmental consciousness. In preserving these species, Americans preserve not just biodiversity but also irreplaceable parts of their national identity. As America faces new challenges, these animal symbols continue to inspire, reminding citizens of both hard-won victories and the ongoing responsibility to protect the natural heritage that has shaped the nation since its beginning.

The enduring connection between these animals and American patriotism demonstrates how deeply the natural world is woven into the nation’s self-conception. From the battlefields where horses and dogs served alongside soldiers to the wilderness where eagles and buffalo represent freedom and abundance, these creatures have helped define what it means to be American. Their stories of courage, resilience, and recovery mirror the American journey itself—complex, sometimes contradictory, but ultimately hopeful in its capacity for renewal and growth.

- 10 Dog Breeds That Rarely Bark - August 23, 2025

- 15 Times Pets Surprised Scientists - August 23, 2025

- 12 Mistakes to Avoid When Photographing Wildlife - August 23, 2025