Florida’s coral reefs, once vibrant underwater ecosystems teeming with marine life, are facing an unprecedented crisis. These magnificent structures, which took thousands of years to form, are disappearing at an alarming rate. The Florida Reef Tract, stretching approximately 360 miles from the Dry Tortugas to the St. Lucie Inlet, is the third largest barrier reef ecosystem in the world and the only living coral barrier reef in the continental United States. Yet today, nearly 90% of the original coral cover has been lost since the 1970s. This article explores the multiple threats endangering these precious marine ecosystems, from rising ocean temperatures to pollution and disease, and what can be done to save them before it’s too late.

The Rising Threat of Ocean Warming

Climate change has emerged as perhaps the most significant threat to Florida’s coral reefs. As global temperatures rise, oceans absorb approximately 90% of this excess heat. In Florida’s waters, temperatures have been increasing steadily, with recent years setting new records for marine heat waves. When water temperatures exceed corals’ tolerance thresholds—typically above 30°C (86°F) for extended periods—they experience thermal stress that triggers a devastating process known as coral bleaching.

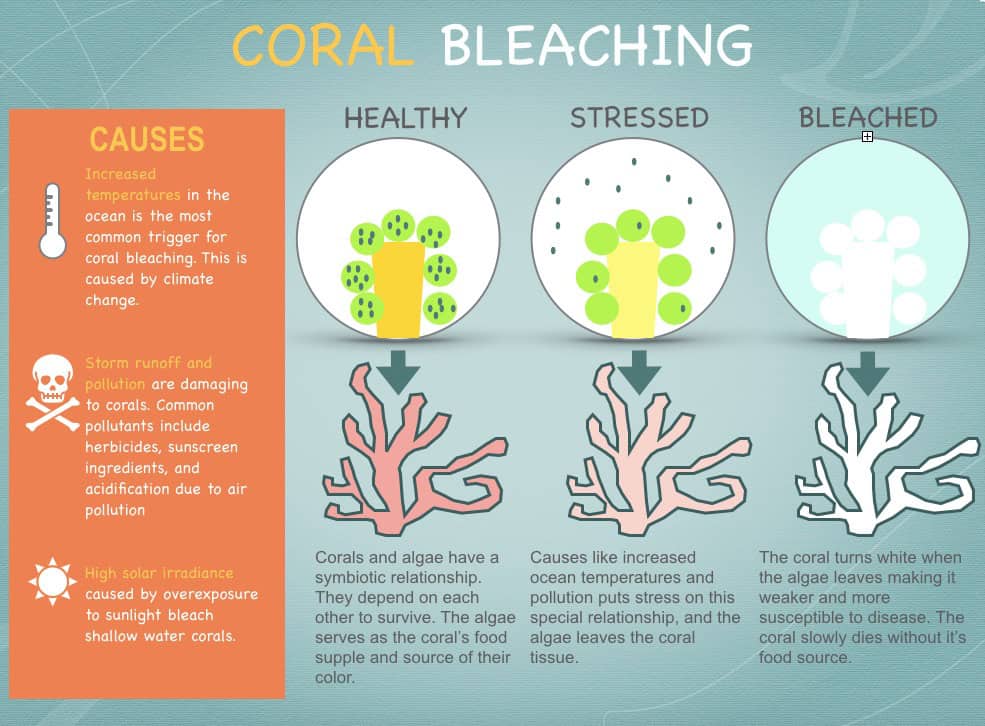

During bleaching events, corals expel the symbiotic algae (zooxanthellae) living in their tissues, which provide them with nutrients through photosynthesis and give them their vibrant colors. Without these algae, corals lose their primary food source and become more susceptible to disease and death. The summer of 2023 saw one of the most severe bleaching events in Florida’s history, with water temperatures reaching as high as 101°F (38.3°C) in some areas—far exceeding the thermal tolerance of most coral species. Scientists estimate that this single event affected over 80% of some coral species in the Florida Keys.

Coral Bleaching: The Visual Warning Sign

Coral bleaching serves as a visible indicator of reef distress. When healthy, corals display a spectrum of colors ranging from browns and greens to pinks and purples, thanks to the pigmented algae living within their tissues. During bleaching events, these once-colorful colonies turn stark white as they expel their algal partners, revealing their transparent tissue and underlying white calcium carbonate skeleton. This process doesn’t immediately kill corals, but it leaves them in a severely weakened state with reduced growth, reproduction capabilities, and disease resistance.

Florida has experienced multiple mass bleaching events since the 1980s, with increasing frequency and severity. What once occurred perhaps once every few decades now happens with alarming regularity. The 2014-2015 global bleaching event severely impacted Florida’s reefs, and before they could fully recover, subsequent thermal stress events in 2019, 2020, and most catastrophically in 2023 further compromised reef health. Research indicates that if a coral colony experiences multiple bleaching events within a short timeframe, its chances of recovery diminish significantly, explaining why Florida’s reefs have struggled to bounce back despite conservation efforts.

Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease: An Unprecedented Epidemic

Since 2014, Florida’s coral reefs have been battling what scientists describe as one of the most lethal coral diseases ever recorded. Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) first appeared near Miami and has since spread throughout the Florida Reef Tract and into the wider Caribbean. This highly contagious disease affects over 20 species of reef-building corals, particularly brain, pillar, star, and boulder corals that form the foundation of reef structures. Once infected, corals can experience mortality rates between 66-100% depending on the species, with tissue death occurring rapidly—sometimes within weeks.

What makes SCTLD particularly devastating is its persistence and lethality. Unlike other coral diseases that may come and go seasonally, SCTLD remains active year-round and continues to spread even years after its initial outbreak. While scientists have determined the disease is likely bacterial in nature and can be transmitted through water, the exact pathogen remains unidentified despite intensive research efforts. Some evidence suggests that stress from warming waters and pollution may increase corals’ susceptibility to the disease, creating a compounding effect alongside other threats facing Florida’s reefs.

Water Quality Degradation and Pollution

Florida’s growing coastal population and intensive agricultural practices have led to significant water quality issues that directly impact coral health. Nutrient pollution—primarily nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizers, sewage, and urban runoff—flows from the mainland into coastal waters, triggering algal blooms that smother coral reefs. These nutrients feed harmful algae that can outcompete corals for space and block essential sunlight from reaching them. A particularly notorious example is the periodic discharges from Lake Okeechobee, which send nutrient-rich freshwater through the St. Lucie and Caloosahatchee rivers into coastal waters, creating “dead zones” and algal blooms.

Beyond nutrients, Florida’s waters contend with a cocktail of other pollutants. Sediment from coastal development and dredging reduces water clarity and can physically smother corals. Chemical contaminants, including pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and petroleum products, compromise coral immune systems and reproductive capabilities. Of growing concern are sunscreen chemicals like oxybenzone and octinoxate, which studies show can damage coral DNA, impair reproduction, and cause bleaching even at very low concentrations. With an estimated 6,000 tons of sunscreen entering reef areas worldwide annually, popular Florida reef sites likely receive significant exposure to these compounds.

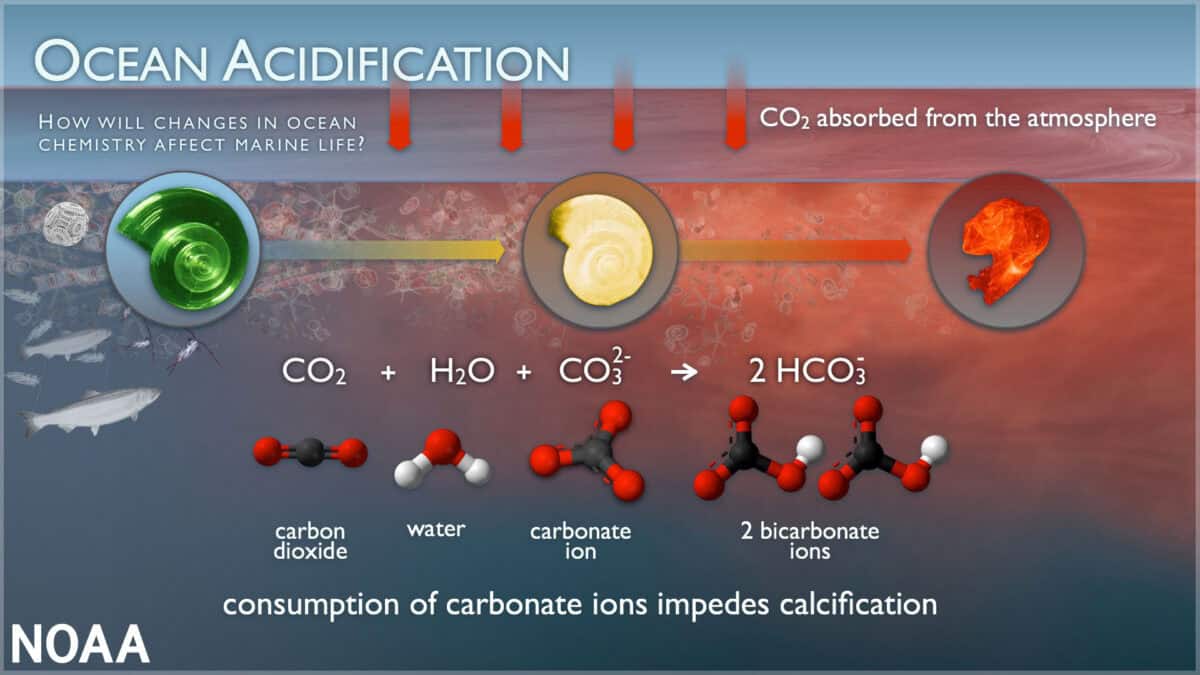

Ocean Acidification: The Chemical Threat

As atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rise due to human activities, oceans absorb approximately 30% of this CO2. While this has temporarily mitigated some atmospheric warming, it has created another problem: ocean acidification. When carbon dioxide dissolves in seawater, it forms carbonic acid, lowering the ocean’s pH and decreasing the availability of carbonate ions that corals need to build their calcium carbonate skeletons. Florida’s waters have experienced a measurable decrease in pH since pre-industrial times, with projections suggesting continued acidification throughout this century.

For corals, acidification presents a metabolic challenge. Building and maintaining their skeletons requires more energy in acidified conditions, forcing corals to divert resources from other vital functions like reproduction and immune response. Studies on Florida’s reefs show that calcification rates (skeleton building) have declined by approximately 15-18% since the 1990s. Additionally, ocean acidification can weaken existing coral skeletons, making reefs more vulnerable to storm damage and bioerosion from organisms that bore into coral structures. Combined with warming temperatures, acidification creates a “one-two punch” that significantly reduces corals’ resilience to other stressors.

Physical Damage from Storms and Human Activities

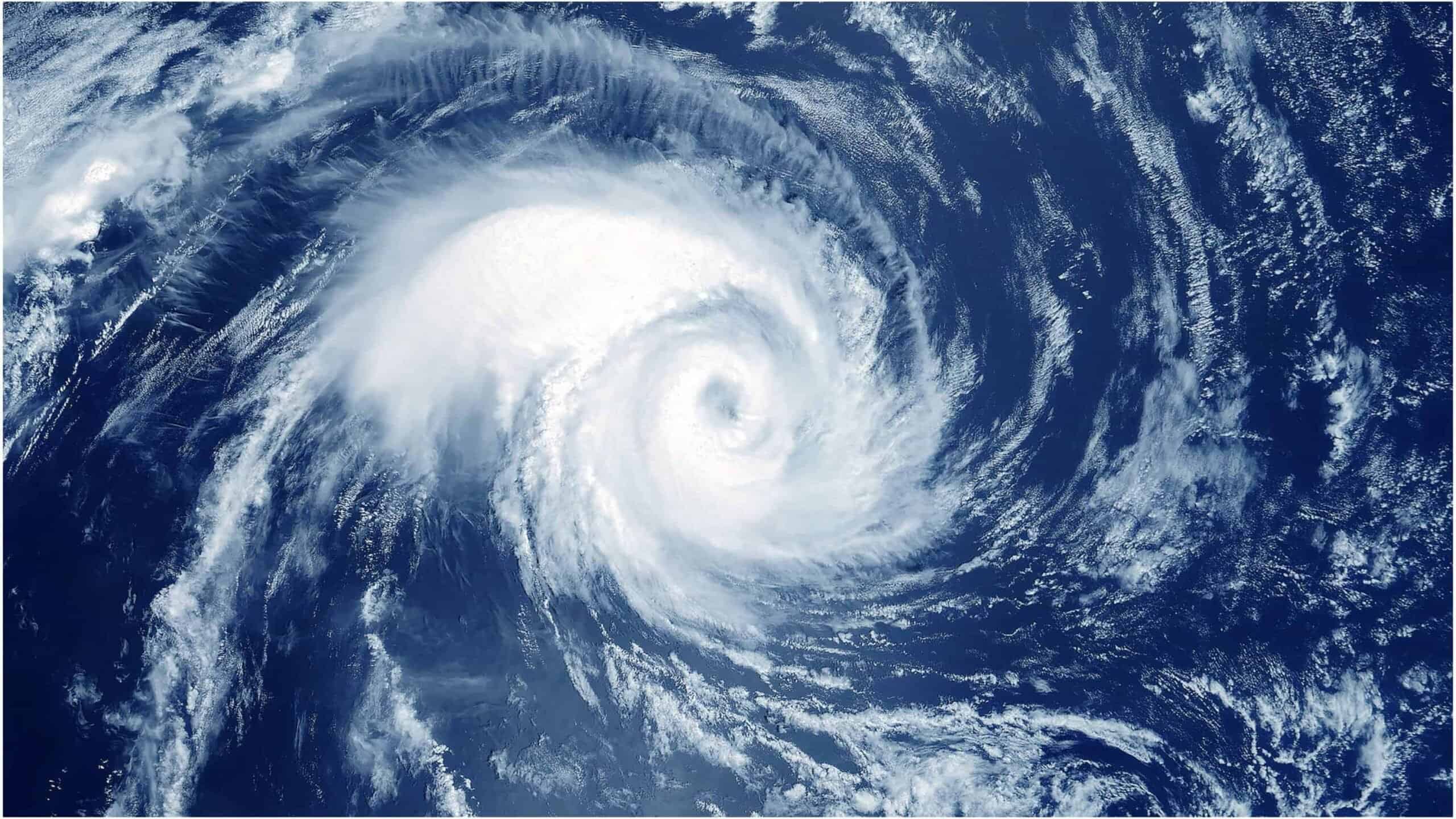

Florida’s position in the hurricane belt means its coral reefs regularly face the mechanical forces of tropical storms and hurricanes. These powerful weather events can cause immediate physical damage to reef structures through wave action and debris impact. Hurricane Irma in 2017, for example, caused extensive damage to Florida Keys reefs, with some sites losing over 40% of their coral cover overnight. While healthy reefs have evolved to withstand and recover from occasional storm events, the combination of increased storm intensity due to climate change and reduced reef resilience from other stressors has diminished this natural recovery capacity.

Human activities contribute additional physical impacts to Florida’s reefs. Ship groundings, anchor damage, and improper diving or snorkeling practices cause direct physical harm to coral colonies. The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary documents hundreds of vessel groundings annually, ranging from small recreational boats to larger commercial vessels. Even minor impacts can create coral rubble fields that are difficult to stabilize and recover. Tourism pressure is also significant, with popular reef sites in the Keys receiving thousands of visitors during peak seasons, increasing the risk of inadvertent damage from fins, hands, or equipment contacting fragile coral structures.

Coastal Development and Habitat Loss

Florida’s coastline has undergone dramatic transformation through development, with natural shorelines replaced by seawalls, marinas, and waterfront properties. This development has destroyed mangrove forests and seagrass beds that serve as natural filters for water flowing toward reefs and as nursery grounds for reef fish. The resulting habitat fragmentation interrupts the connectivity between these ecosystems that many marine species depend on throughout their life cycles. As reef fish populations decline due to habitat loss in these supporting ecosystems, coral reefs lose the ecological services these fish provide, such as controlling algae growth and cycling nutrients.

Coastal construction also increases sedimentation and turbidity in nearshore waters. Dredging for shipping channels, beach renourishment projects, and shoreline hardening all release sediments that can travel to reef areas. These suspended particles reduce water clarity, blocking essential sunlight from reaching corals and potentially smothering them when particles settle. Port expansion projects, such as those in Miami and Fort Lauderdale, have been particularly controversial for their impacts on nearby reef systems. The Port Miami dredging project completed in 2015 was estimated to have buried over 250 acres of coral reef habitat in sediment, despite mitigation measures being in place.

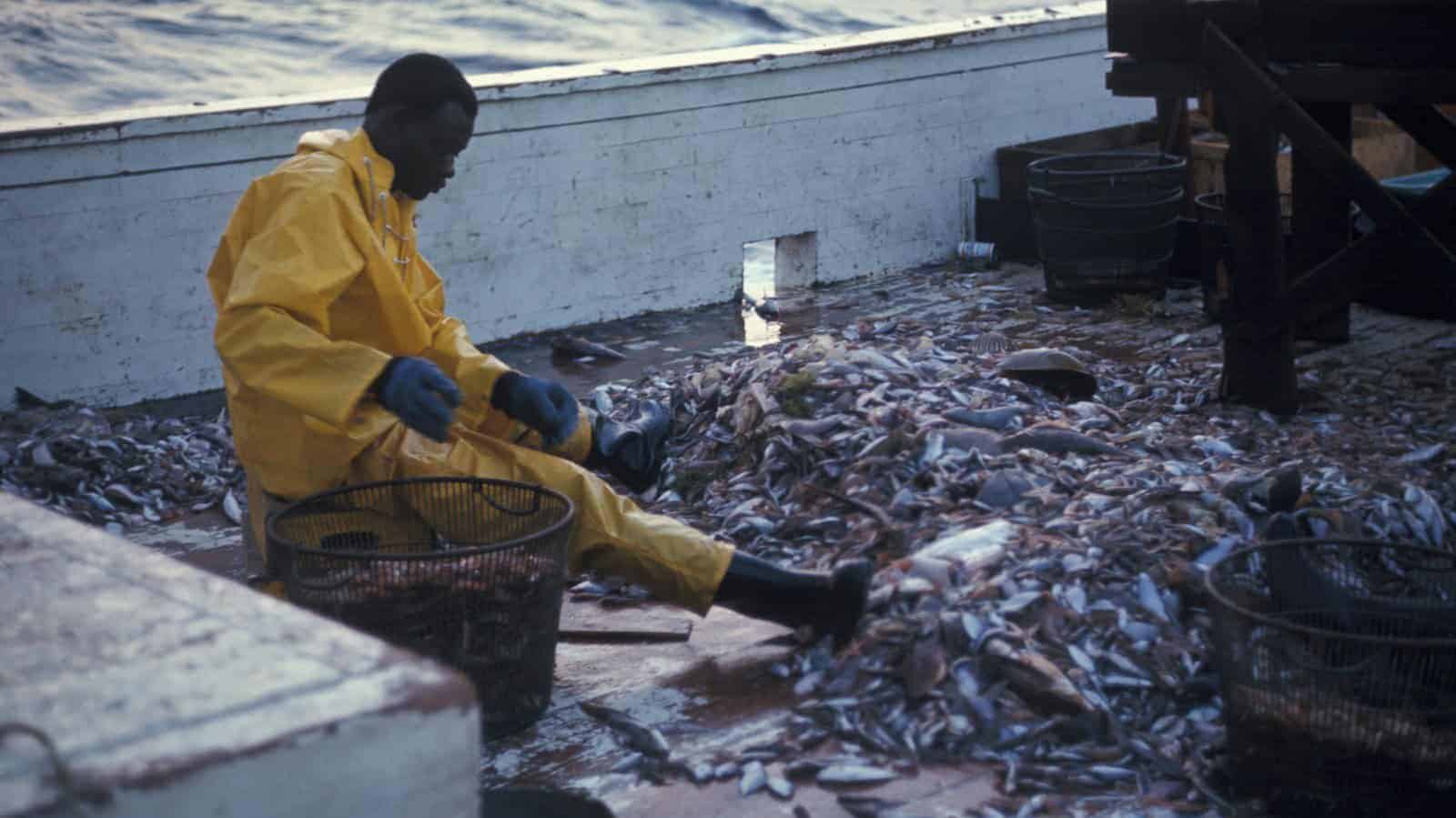

Overfishing and Ecological Imbalance

Fishing pressure on Florida’s reefs has altered the ecological balance critical for reef health. The removal of herbivorous fish like parrotfish and surgeonfish reduces natural algae control, allowing algae to outcompete corals for space. Similarly, the historical overharvesting of predatory species like groupers and snappers has cascading effects through the food web. Fishing pressure on Florida’s reefs continues despite regulations, with both commercial and recreational fishing removing significant biomass annually. Studies comparing protected and fished areas within the Florida Keys show marked differences in fish abundance, size, and community structure.

The removal of key grazers has become especially problematic as nutrients from land-based sources fuel algal growth. Without sufficient herbivores to keep algae in check, many degraded reef areas have undergone phase shifts from coral-dominated to algae-dominated systems—a transition that is difficult to reverse. Additionally, fishing gear can cause direct physical damage to reefs. Ghost fishing gear—lost or abandoned nets, lines, and traps—continues to entangle marine life and damage corals long after being discarded. Though efforts to retrieve ghost gear have increased, an estimated 1,000 pounds of derelict fishing gear is removed from Florida Keys reefs annually, indicating the scale of the problem.

Invasive Species: The Lionfish Problem

Among the numerous challenges facing Florida’s coral reefs, invasive species have emerged as a significant threat, with the Indo-Pacific lionfish (Pterois volitans and P. miles) representing the most problematic invader. First reported off Florida’s coast in the 1980s, lionfish have since established dense populations throughout the state’s reef systems. These striking but voracious predators consume enormous quantities of native reef fish—up to 30 times their stomach volume daily—with studies documenting reduction of native fish populations by up to 80% in heavily invaded areas. Their consumption of herbivorous fish is particularly concerning, as it indirectly promotes algal overgrowth on corals.

Lionfish possess several characteristics that make them particularly successful invaders. They reproduce year-round, with females capable of releasing up to 30,000 eggs every few days. They have no natural predators in Atlantic waters, and their venomous spines deter would-be predators from learning to target them. Removal efforts through spearfishing tournaments and promoting lionfish consumption have had some localized success but struggle to control populations across the full extent of Florida’s reefs. Other invasive species of concern include certain macroalgae, like Caulerpa taxifolia, which can rapidly overgrow reef substrates and displace native species, further stressing Florida’s already vulnerable coral ecosystems.

Conservation Efforts and Restoration Projects

In response to the reef crisis, Florida has become a hub for innovative coral conservation and restoration efforts. The Coral Restoration Foundation, headquartered in Key Largo, operates the world’s largest coral nursery, growing thousands of corals on underwater “trees” before outplanting them to degraded reef areas. These nurseries focus primarily on staghorn and elkhorn corals, critically endangered species that were once dominant reef-builders in Florida. Mote Marine Laboratory’s coral restoration program has pioneered microfragmentation techniques that accelerate coral growth rates up to 50 times faster than natural rates, particularly for slow-growing boulder and brain corals. Together, these organizations have outplanted over 150,000 corals to Florida reefs in recent years.

Beyond direct restoration, significant policy and management efforts aim to reduce threats to reef systems. The Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary, established in 1990, encompasses 2,900 square nautical miles of waters surrounding the Florida Keys, including protected areas where fishing and other extractive activities are prohibited. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection coordinates the Florida Reef Tract Coral Disease Response team, which implements disease intervention treatments like applying antibiotics to affected corals and establishing coral genetic repositories to preserve diversity. Additionally, improved wastewater infrastructure projects throughout South Florida aim to reduce nutrient pollution reaching coral reefs, though progress has been slower than reef scientists recommend.

Future Outlook and Technological Solutions

The future of Florida’s coral reefs likely depends on both global climate action and innovative local solutions. Assisted evolution approaches are gaining traction, with researchers selectively breeding corals for heat tolerance and disease resistance. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has developed a program called “Mission: Iconic Reefs,” a 20-year, $100 million restoration plan targeting seven iconic reef sites in the Florida Keys. This comprehensive approach combines outplanting at unprecedented scales with habitat preparation, predator control, and genetic diversity considerations. Meanwhile, technologies like 3D printing are being used to create artificial reef structures that mimic the complexity of natural reefs and provide settlement substrates for coral larvae.

Another promising frontier involves enhancing the beneficial bacteria associated with corals through probiotics. Researchers at the University of Miami and other institutions are identifying bacterial strains that boost coral immunity and resilience to environmental stressors. Some studies show that certain bacterial treatments can reduce the mortality of corals exposed to thermal stress by up to 40%. Similarly, experiments with temporary shading or cooling technologies during extreme heat events could potentially prevent mass bleaching. While none of these approaches alone can save Florida’s reefs, their combined implementation alongside meaningful climate action offers the best hope for preserving some reef function and biodiversity into the future.

Florida’s coral reefs stand at a critical crossroads, facing an unprecedented combination of threats that have already decimated large portions of what was once a thriving marine ecosystem. The loss of these reefs represents not just an ecological tragedy but an economic one as well, with Florida’s reef-related tourism, fisheries, and coastal protection services valued at over $8.5 billion annually. The science is clear that without immediate, decisive action on multiple fronts—from global carbon emissions reduction to local water quality improvements and direct restoration interventions—we risk losing one of America’s most valuable natural resources within a generation. Yet amidst the sobering reality, there are reasons for cautious optimism in the innovative solutions being developed and the growing public awareness about the importance of these underwater ecosystems. The future of Florida’s coral reefs ultimately depends on our collective willingness to make the necessary changes and investments to ensure these ancient, living structures continue to thrive for generations to come.

- Why Some Birds Are Singing Louder in Urban Areas - August 10, 2025

- Why Vultures Are Smarter Than You Think - August 10, 2025

- How Foxes Use Stealth to Evade Predators - August 10, 2025