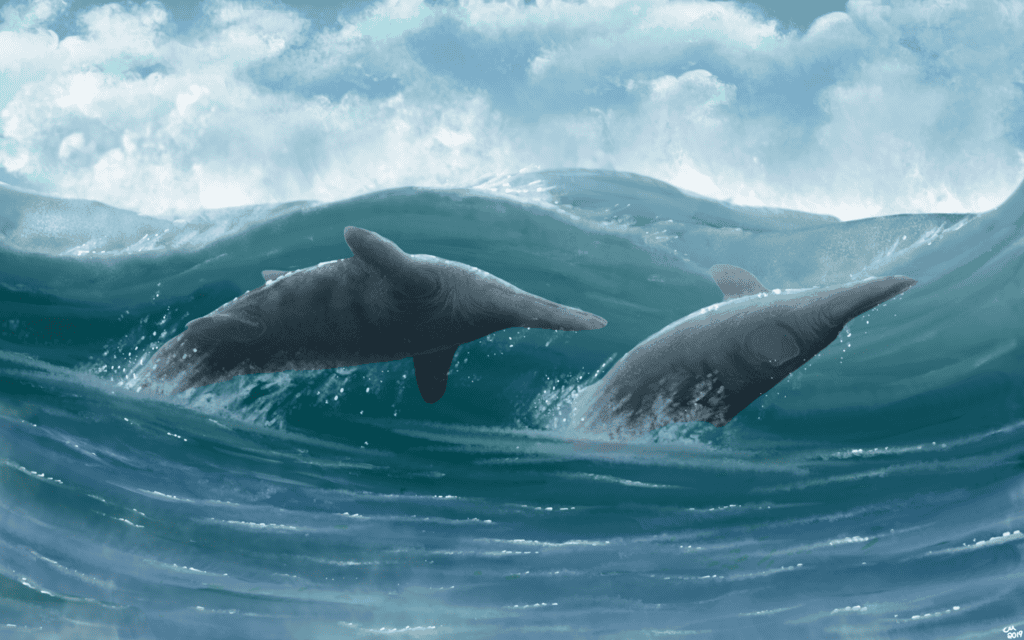

Imagine diving into ancient oceans 250 million years ago, where sleek, torpedo-shaped creatures sliced through the water with dolphin-like grace. These weren’t mammals, though—they were reptiles that had made the extraordinary transition from land back to sea. Ichthyosaurs, literally meaning “fish lizards,” represent one of evolution’s most remarkable success stories, dominating marine ecosystems for over 150 million years before mysteriously vanishing from the fossil record.

Their story begins in the aftermath of the greatest extinction event our planet has ever witnessed. As life struggled to recover from the Permian-Triassic extinction, these pioneering reptiles seized an opportunity that would reshape marine ecosystems forever. They evolved from humble land-dwelling ancestors into ocean predators that would make even today’s apex marine hunters look modest in comparison.

Ancient Origins in a World Reborn

The early Triassic period, roughly 250 million years ago, marked the beginning of the ichthyosaur saga. Earth was still recovering from the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction that had wiped out 96% of marine species. In this ecological vacuum, early reptiles found unprecedented opportunities in the oceans.

The first ichthyosaurs were nothing like their later descendants. These primitive forms, such as Chaohusaurus from China, were small, eel-like creatures with elongated bodies and paddle-like limbs. They retained many terrestrial features, including visible necks and less streamlined bodies, suggesting their recent transition from land to sea.

Fossil evidence from this period reveals a rapid evolutionary experiment. Within just a few million years, these early pioneers were diversifying into multiple lineages, each testing different approaches to aquatic life. Some remained small and nimble, while others began the journey toward becoming the ocean giants that would define their legacy.

The Great Transformation

By the Middle Triassic, ichthyosaurs had undergone one of the most dramatic evolutionary transformations in vertebrate history. Their bodies became increasingly streamlined, developing the classic dolphin-like silhouette that would serve them so well. This wasn’t just surface-level change—their entire anatomy was being revolutionized.

The most striking development was their limb modification. What had once been legs became powerful flippers, perfectly adapted for underwater propulsion. Their vertebral columns developed the distinctive downward bend that supported their shark-like tail fins, creating an incredibly efficient swimming apparatus.

Perhaps most remarkably, their skulls began elongating into the characteristic pointed snouts that would become their trademark. This adaptation allowed them to slice through water with minimal resistance while providing the perfect platform for catching fast-moving prey. The transformation was so complete that early paleontologists actually mistook them for ancient fish.

Masters of Convergent Evolution

What makes ichthyosaurs truly extraordinary is how closely they came to resemble modern dolphins and sharks, despite being reptiles. This phenomenon, known as convergent evolution, demonstrates how similar environmental pressures can shape completely unrelated animals into nearly identical forms. The parallels are so striking that it’s almost unsettling.

Like dolphins, ichthyosaurs developed echolocation abilities, using sound waves to navigate murky waters and locate prey. Their brain structures, preserved in exceptional fossils, show enlarged auditory regions that mirror those found in modern toothed whales. They even developed similar social behaviors, with evidence suggesting they traveled in pods and exhibited complex hunting strategies.

The similarities extend to their reproductive strategies as well. Both groups evolved live birth, abandoning the egg-laying habits of their ancestors. This adaptation allowed them to remain fully aquatic throughout their life cycles, never needing to return to land for reproduction. It’s a testament to evolution’s remarkable ability to find similar solutions to environmental challenges.

The Jurassic Golden Age

The Jurassic period marked the absolute pinnacle of ichthyosaur diversity and success. During this time, roughly 200 to 145 million years ago, these marine reptiles reached sizes and achieved ecological dominance that would never be equaled again. The oceans were their kingdom, and they ruled it with unmatched efficiency.

Species like Temnodontosaurus reached lengths of up to 40 feet, making them among the largest predators in Jurassic seas. Their massive jaws, lined with teeth the size of bananas, could crush the shells of giant ammonites or tear apart large marine reptiles. These weren’t just big fish—they were apex predators with the intelligence and hunting skills to match their size.

The diversity during this period was staggering. From the massive Shastasaurus, potentially reaching 70 feet in length, to the more modest but incredibly common Ichthyosaurus, the group had evolved to fill virtually every marine ecological niche. Some specialized in deep-sea hunting, others patrolled shallow coastal waters, and still others developed filter-feeding adaptations similar to modern baleen whales.

Giants of the Deep

The sheer size of some ichthyosaur species defies imagination. Shastasaurus siculus, discovered in British Columbia, may have reached lengths of up to 70 feet, making it one of the largest marine reptiles ever discovered. To put this in perspective, that’s larger than most modern whales and would have made even the fearsome Megalodon look modest.

These giants weren’t just impressive for their size—they were marvels of biological engineering. Their massive bodies were supported by incredibly strong vertebral columns, with individual vertebrae the size of dinner plates. Their flippers, some measuring over 6 feet in length, could generate enormous thrust for such massive creatures.

Recent discoveries have revealed even more impressive specimens. Himalayasaurus, found in Tibet, represents another giant that dominated ancient Tethys Sea. These discoveries keep pushing the boundaries of what we thought possible for marine reptiles, suggesting that the oceans of the past supported ecosystems far more diverse and spectacular than anything we see today.

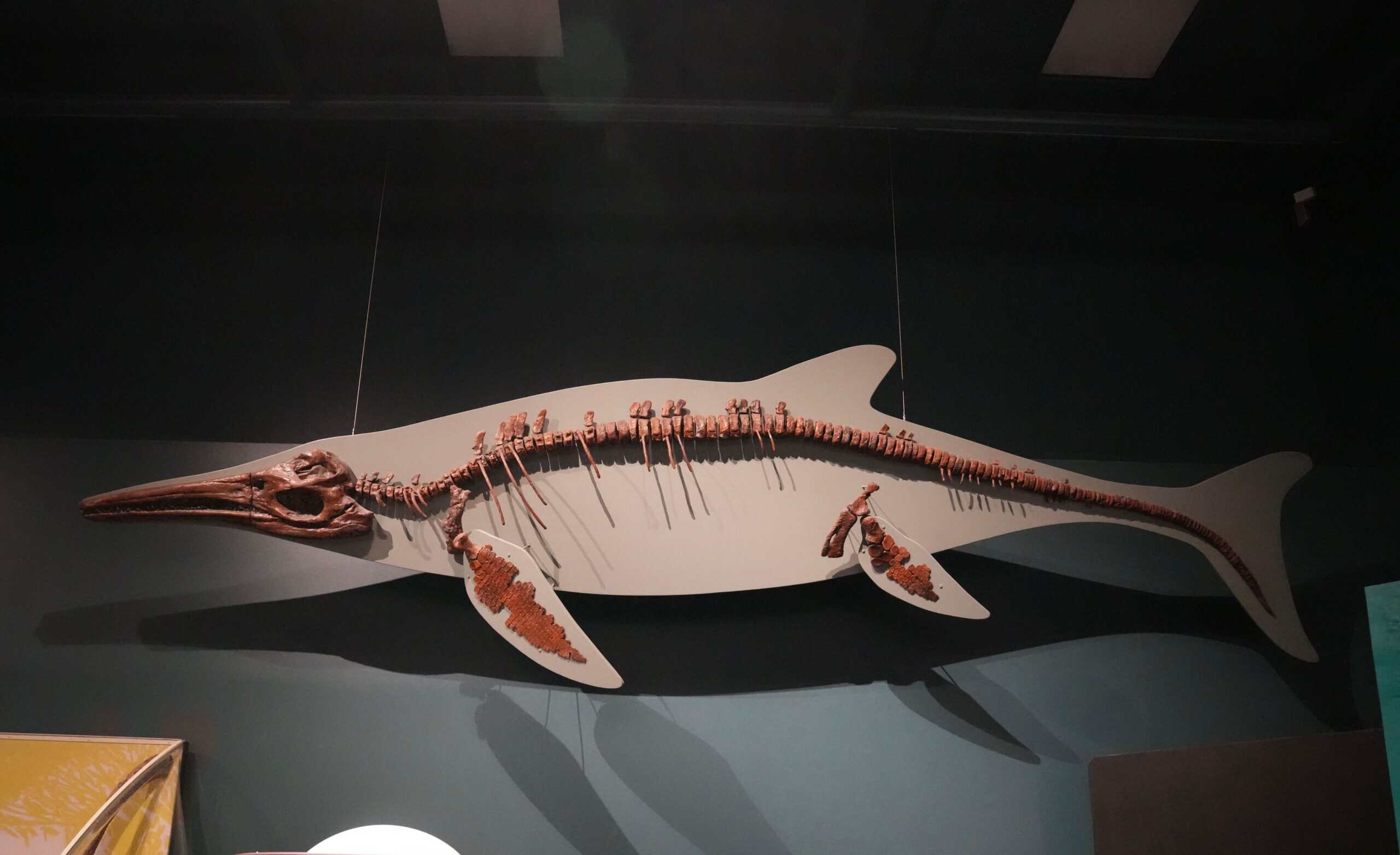

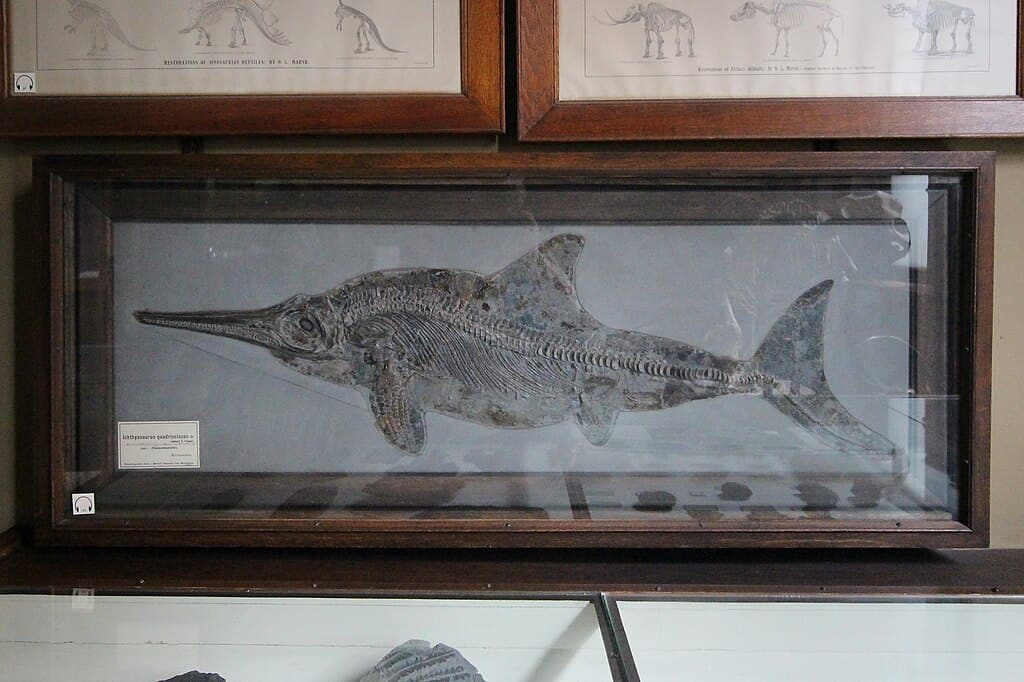

Exceptional Preservation and Fossil Windows

The Holzmaden Shale in Germany provides us with perhaps the most extraordinary window into ichthyosaur life ever discovered. These 180-million-year-old deposits preserve ichthyosaurs in such exquisite detail that we can see their last meals, their soft tissues, and even their young still inside their bodies. It’s like having a time machine that shows us these creatures as they actually lived.

One of the most famous specimens shows a female ichthyosaur giving birth, with the baby emerging tail-first—exactly like modern dolphins and whales. This fossil provides direct evidence of their live-birth strategy and shows how perfectly adapted they were to aquatic life. The level of preservation is so exceptional that we can even see the outline of their dorsal fins and the shape of their eyes.

The Holzmaden fossils also reveal the incredible diversity of ichthyosaur diets. Stomach contents show everything from squid-like belemnites to fish, ammonites, and even other marine reptiles. Some specimens contain hundreds of tiny hooklets from squid tentacles, suggesting these predators could tackle prey much larger than themselves. The preservation quality allows us to understand their ecology in ways that would be impossible with typical fossils.

Revolutionary Reproductive Strategies

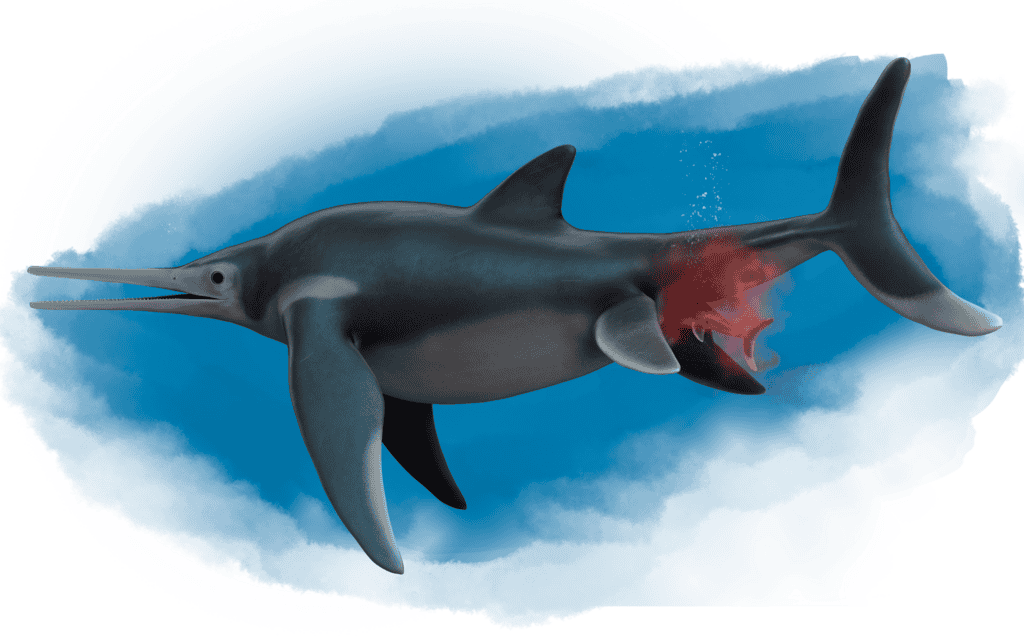

Perhaps nothing illustrates the complete aquatic adaptation of ichthyosaurs better than their reproductive revolution. Unlike their egg-laying reptilian ancestors, ichthyosaurs evolved live birth, allowing them to remain in the ocean throughout their entire life cycle. This wasn’t just a minor adaptation—it was a complete physiological overhaul that required massive changes to their anatomy.

The most remarkable aspect of their reproduction was the tail-first birth strategy, identical to that used by modern dolphins and whales. This adaptation prevents the newborn from drowning during the birth process, as the head emerges last, allowing the baby to take its first breath immediately upon full emergence. Fossil evidence shows baby ichthyosaurs emerging in exactly this position, frozen in time during the birth process.

Their reproductive strategy also included extended parental care, with evidence suggesting mothers nursed their young for extended periods. Large ichthyosaur species likely had gestation periods lasting over a year, similar to modern large whales. This investment in fewer, but more developed offspring, was a key factor in their evolutionary success and mirrors the strategies of today’s most intelligent marine mammals.

The Eyes Have It

Ichthyosaurs possessed some of the largest eyes in the animal kingdom, both ancient and modern. The largest specimens had eyes measuring over 10 inches in diameter—bigger than dinner plates and larger than those of any known vertebrate. These massive visual organs weren’t just for show; they were precision instruments designed for life in the ocean’s depths.

The enormous eyes were perfectly adapted for low-light conditions, allowing ichthyosaurs to hunt effectively in deep waters where sunlight barely penetrates. The eye structure, preserved in exceptional detail in some fossils, shows adaptations for both near and far vision, suggesting these predators could spot prey at considerable distances while also focusing on close targets during attacks.

Recent analysis of ichthyosaur eye fossils has revealed another remarkable adaptation: they likely had excellent color vision and could even see into the ultraviolet spectrum. This gave them a significant advantage in detecting prey that might be invisible to other predators. The combination of massive size and sophisticated optics made ichthyosaur eyes among the most advanced sensory organs in the prehistoric world.

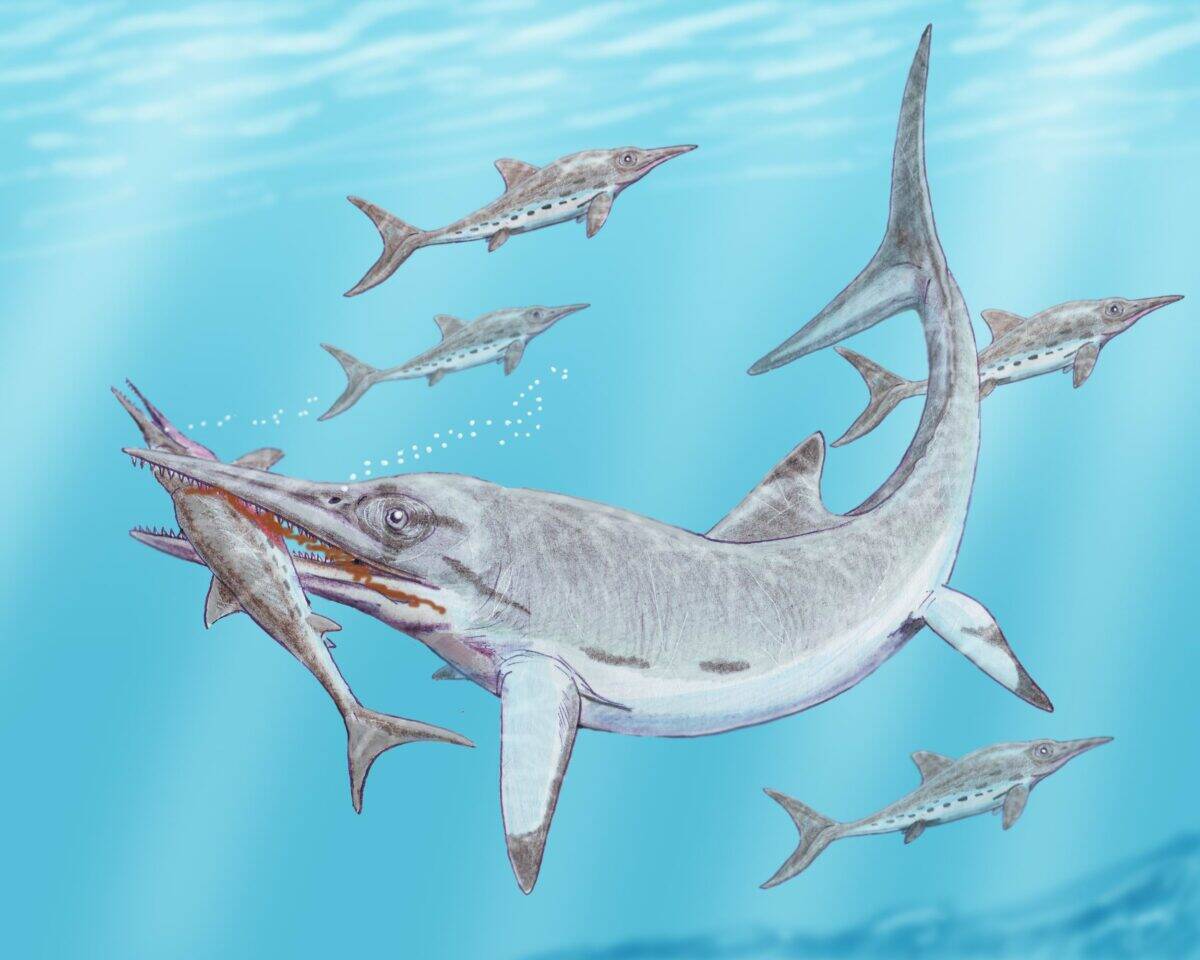

Sophisticated Hunting Strategies

Evidence from fossil sites suggests ichthyosaurs employed hunting strategies that rival those of modern dolphins and orcas. Group hunting appears to have been common, with multiple individuals working together to corral schools of fish or attack larger prey. Bite marks on fossils and the distribution of specimens in some deposits point to coordinated pack behavior.

The variety of hunting strategies matched their incredible diversity. Small, agile species like Mixosaurus were pursuit predators, chasing down fast-moving fish and squid with bursts of speed. Larger species like Temnodontosaurus were ambush predators, using their massive size to surprise prey from below. Some even developed suction feeding, similar to modern sperm whales hunting squid in the deep ocean.

Archaeological evidence from coprolites (fossilized feces) reveals the sophisticated dietary preferences of different ichthyosaur species. Some were specialists, feeding almost exclusively on certain types of squid or fish, while others were generalists that would consume whatever was available. This dietary flexibility was crucial to their long-term success, allowing them to adapt to changing ocean conditions and prey availability.

Breathing Innovations

As air-breathing reptiles living entirely in water, ichthyosaurs faced unique respiratory challenges that required innovative solutions. Their nostrils evolved into specialized structures positioned on top of their heads, similar to the blowholes of modern whales. This adaptation allowed them to breathe efficiently while spending minimal time at the surface.

The positioning and structure of their nostrils suggests they could take rapid breaths without fully surfacing, much like modern dolphins. Fossil evidence indicates they could hold their breath for extended periods, possibly up to an hour or more for larger species. This capability was essential for deep-sea hunting, where prey might be found hundreds of feet below the surface.

Their respiratory system also included specialized adaptations for pressure changes during deep dives. The ribcage structure of larger ichthyosaurs shows modifications that would have allowed their lungs to collapse safely under pressure, preventing nitrogen narcosis and decompression sickness. These adaptations parallel those found in modern deep-diving marine mammals, once again demonstrating the power of convergent evolution.

The Cretaceous Decline

The beginning of the end for ichthyosaurs came during the Cretaceous period, roughly 145 million years ago. After dominating marine ecosystems for over 100 million years, these masters of the ocean began to face unprecedented challenges. The rise of new predators and changing ocean conditions created a perfect storm that would eventually lead to their extinction.

The most significant threat came from the emergence of mosasaurs, giant marine lizards that were faster, more agile, and potentially more intelligent than their ichthyosaur contemporaries. These newcomers competed directly with ichthyosaurs for the same prey and occupied similar ecological niches. The competition was fierce, and the established order of the oceans began to crumble.

Climate change also played a crucial role in their decline. Falling sea levels and changing ocean temperatures disrupted the marine ecosystems that ichthyosaurs had dominated for so long. The stable, warm seas that had supported their incredible diversity were being replaced by more variable and challenging conditions. Species that had thrived for millions of years suddenly found themselves struggling to adapt to rapidly changing environments.

The Final Curtain

The last ichthyosaurs disappeared from the fossil record around 90 million years ago, approximately 25 million years before the famous asteroid impact that killed the dinosaurs. Their extinction wasn’t sudden—it was a gradual decline that saw species after species vanishing until none remained. The oceans that had once teemed with these magnificent creatures fell silent.

The final ichthyosaur species were shadows of their former glory. Gone were the giants of the Jurassic; the last survivors were smaller, more specialized forms that had retreated to specific ecological niches. Even these hardy survivors couldn’t withstand the combined pressures of competition, climate change, and ecosystem disruption.

What makes their extinction particularly poignant is how successful they had been. For over 150 million years, they had proven that reptiles could not only survive in the ocean but dominate it completely. Their disappearance marked the end of an era and left ecological niches vacant that wouldn’t be filled until the rise of modern whales and dolphins millions of years later.

Evolutionary Innovations That Outlasted Them

Despite their extinction, ichthyosaurs left an indelible mark on evolutionary history. Many of their innovations would later be “rediscovered” by mammals making their own transition to marine life. The parallel evolution between ichthyosaurs and modern cetaceans is so striking that it provides one of the best examples of convergent evolution in the fossil record.

Their body plan was so successful that it would be independently evolved by sharks (which are much older but achieved their modern form later), dolphins, and even some extinct marine crocodiles. The torpedo-shaped body, powerful tail, and streamlined flippers represent the optimal design for fast, efficient swimming—a template that evolution has returned to repeatedly.

The respiratory adaptations of ichthyosaurs also pioneered solutions that would later appear in marine mammals. Their specialized nostrils, pressure-resistant ribcages, and ability to hold their breath for extended periods were innovations that would prove essential for any large air-breathing animal living in the ocean. In many ways, ichthyosaurs were the beta test for marine reptile success.

Modern Discoveries and New Insights

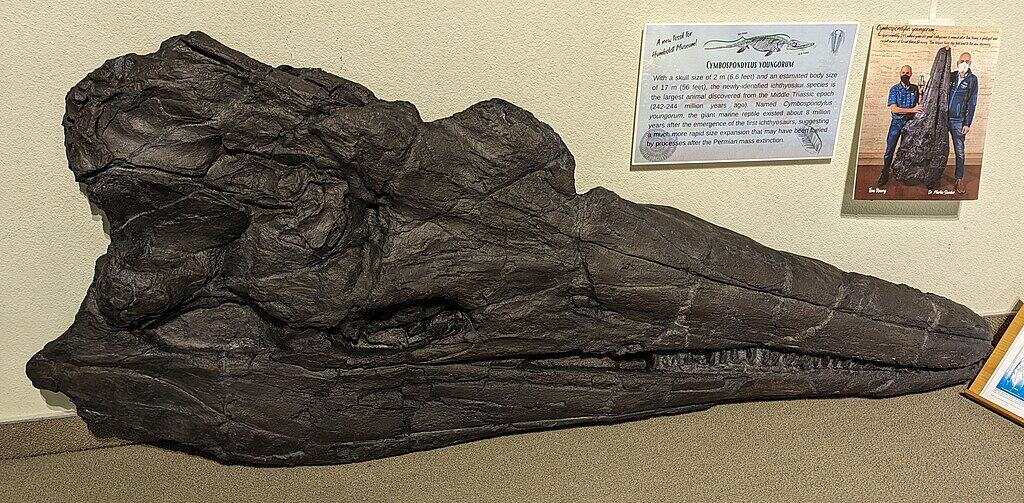

Recent paleontological discoveries continue to revolutionize our understanding of ichthyosaurs. In 2018, the discovery of Cymbospondylus youngorum in Nevada revealed that ichthyosaurs reached giant sizes much earlier than previously thought. This 60-foot-long predator lived just 3 million years after the first ichthyosaurs appeared, suggesting their evolutionary transformation was even more rapid than scientists had imagined.

Advanced imaging techniques are revealing details about ichthyosaur biology that were impossible to detect just a few decades ago. CT scans of fossils have shown the internal structure of their organs, the development of their young, and even the contents of their stomachs. These technologies are literally allowing us to see inside these ancient creatures and understand their lives in unprecedented detail.

Molecular analysis of exceptionally well-preserved specimens has even revealed some aspects of their genetics and cellular structure. While we can’t extract DNA from fossils this old, other biomolecules can sometimes survive, providing clues about their metabolism, growth rates, and even their coloration. Each new discovery adds another piece to the puzzle of understanding these remarkable creatures.

The Whale Connection

The similarities between ichthyosaurs and modern whales extend far beyond their physical appearance. Both groups evolved from terrestrial ancestors, made the dramatic transition to fully aquatic life, and developed remarkably similar solutions to the challenges of marine existence. The parallels are so extensive that studying ichthyosaurs helps us understand the evolutionary pressures that shaped modern marine mammals.

Both groups evolved similar social structures, with evidence suggesting ichthyosaurs lived in pods and exhibited complex social behaviors. Fossil assemblages show multiple individuals of different ages together, suggesting family groups and possibly even multi-generational social structures. The communication methods may have been similar too, with both groups likely using a combination of visual signals, physical contact, and potentially even primitive echolocation.

The reproductive strategies of both groups represent convergent solutions to the challenge of raising young in an aquatic environment. Live birth, extended parental care, and the production of relatively few but well-developed offspring characterize both ichthyosaurs and modern whales. This suggests that these strategies represent optimal solutions for large marine vertebrates, regardless of their evolutionary origin.

Lessons from the Deep

The rise and fall of ichthyosaurs offers profound lessons about evolution, adaptation, and extinction. Their story demonstrates that even the most successful and well-adapted organisms can face extinction when environmental conditions change rapidly. After dominating marine ecosystems for over 150 million years, they couldn’t adapt quickly enough to survive the challenges of the Cretaceous period.

Their extinction also highlights the importance of ecological flexibility. The ichthyosaur species that survived longest were those that could adapt to changing conditions and exploit new opportunities. The specialists that had evolved for very specific ecological niches were the first to disappear when those niches changed or disappeared.

Perhaps most importantly, ichthyosaurs show us that evolution is not a linear progression toward “better” forms, but rather a constant process of adaptation to changing environments. Their incredible success was followed by complete extinction, reminding us that no species, no matter how well-adapted, is guaranteed survival in the face of environmental change.

The Legacy Lives On

Today, ichthyosaurs continue to inspire and educate us about the history of life on Earth. Their fossils grace museums worldwide, captivating visitors with their alien beauty and remarkable preservation. Children who encounter these ancient marine reptiles often develop a lifelong fascination with paleontology and natural history, ensuring that their legacy continues to inspire new generations of scientists.

The study of ichthyosaurs has also contributed significantly to our understanding of marine ecosystems and evolution. Their fossil record provides crucial data about ancient ocean conditions, climate change, and the long-term effects of environmental disruption. This information is increasingly relevant as we face our own period of rapid environmental change.

Modern conservation efforts often draw inspiration from the ichthyosaur story. Their extinction serves as a reminder of the fragility of marine ecosystems and the importance of protecting the ocean environments that support today’s marine life. The parallels between ichthyosaurs and modern marine mammals make their story particularly relevant to current conservation challenges.

Conclusion

The story of ichthyosaurs is ultimately a tale of triumph and tragedy, of evolutionary innovation and environmental vulnerability. For over 150 million years, these remarkable reptiles ruled the oceans with an efficiency and elegance that wouldn’t be matched until the rise of modern whales and dolphins. Their transformation from land-dwelling reptiles to ocean masters represents one of evolution’s greatest success stories.

Yet their extinction reminds us that even the most successful adaptations can become evolutionary dead ends when environments change too rapidly. The ichthyosaurs that once dominated every ocean on Earth left behind only fossils and the memory of their remarkable journey. Their legacy lives on in the convergent evolution of modern marine mammals and in the lessons they teach us about adaptation, survival, and the ever-changing nature of life on Earth.

What strikes me most about these ancient ocean dwellers is how they achieved something that seems almost impossible—they became perfect marine predators while carrying the fundamental constraints of their reptilian heritage. Did you expect that a group of animals could dominate the oceans for longer than mammals have even existed?

- This Bat Colony Is the Largest Mammal Gathering in North America - August 7, 2025

- These Giant Jellyfish Keep Washing Up on U.S. Beaches - August 7, 2025

- This Animal Sleeps with One Eye Open — Literally - August 7, 2025