Rainforests are Earth’s most biologically diverse ecosystems, housing over 50% of the world’s plant and animal species while covering less than 6% of the global land surface. These lush environments provide food, shelter, and specialized habitats for countless creatures that have evolved to thrive within their multi-layered canopies, humid understories, and nutrient-rich forest floors. As rainforests face unprecedented threats from deforestation, climate change, and human encroachment, understanding the animals that rely on these ecosystems becomes increasingly important. From microscopic insects to magnificent mammals, rainforest-dependent species showcase remarkable adaptations and ecological relationships that highlight the fragility and interconnectedness of these vital habitats. This article explores the diverse animals that cannot survive without rainforests and examines why their preservation is critical for maintaining global biodiversity.

The Remarkable Biodiversity of Rainforests

Rainforests represent the pinnacle of terrestrial biodiversity, containing an estimated 50% of Earth’s species in just 6% of its land area. The Amazon rainforest alone hosts approximately 2.5 million insect species, 40,000 plant species, 1,300 bird species, and hundreds of mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. This extraordinary concentration of life is made possible by the rainforest’s unique structure, with multiple vertical layers creating countless microhabitats, each with specific temperature, humidity, and light conditions. Additionally, rainforests receive abundant rainfall (typically over 80 inches annually) and maintain relatively stable year-round temperatures, allowing for continuous growth and biological activity. These conditions have fostered millions of years of evolution and specialization, resulting in complex ecological relationships where many species have become entirely dependent on specific rainforest conditions, plants, or other animals for their survival.

Primates: The Canopy Specialists

Primates represent some of the most charismatic and vulnerable rainforest-dependent animals. Species like orangutans in Southeast Asian rainforests and spider monkeys in Central and South American forests have evolved specifically for life in the canopy, with specialized limbs and prehensile tails that allow them to move efficiently through the trees. The critically endangered orangutan, for instance, spends over 95% of its life in the forest canopy, building nightly nests in different trees and relying on over 500 different rainforest plant species for food. Similarly, numerous monkey species, including the golden lion tamarin of Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, depend on specific rainforest fruits and have co-evolved with the plants that produce them, often serving as important seed dispersers. The loss of rainforest habitat has catastrophic consequences for these primates, as they cannot adapt to alternative environments. For example, orangutan populations have declined by more than 80% in the last 75 years, primarily due to rainforest destruction for palm oil plantations in Borneo and Sumatra.

Big Cats of the Rainforest

Several of the world’s most powerful predators are rainforest specialists that require these dense habitats for hunting and breeding. The jaguar, the largest cat in the Americas, is perfectly adapted to rainforest life with a stocky build that allows it to navigate dense vegetation and exceptional swimming abilities to cross rainforest rivers. These apex predators require large, intact rainforest territories of up to 50 square miles per individual to maintain healthy populations. Similarly, the clouded leopard of Southeast Asian rainforests has evolved specialized adaptations for arboreal hunting, including the longest canine teeth relative to body size of any cat and extremely flexible ankle joints that allow it to climb down trees headfirst. The rare and elusive tigers that inhabit rainforests in places like Sumatra depend on dense forest cover for stalking prey and raising cubs. All these big cats face significant threats from rainforest fragmentation and destruction, which reduces their territory size, cuts off migration routes, and brings them into increasing conflict with humans.

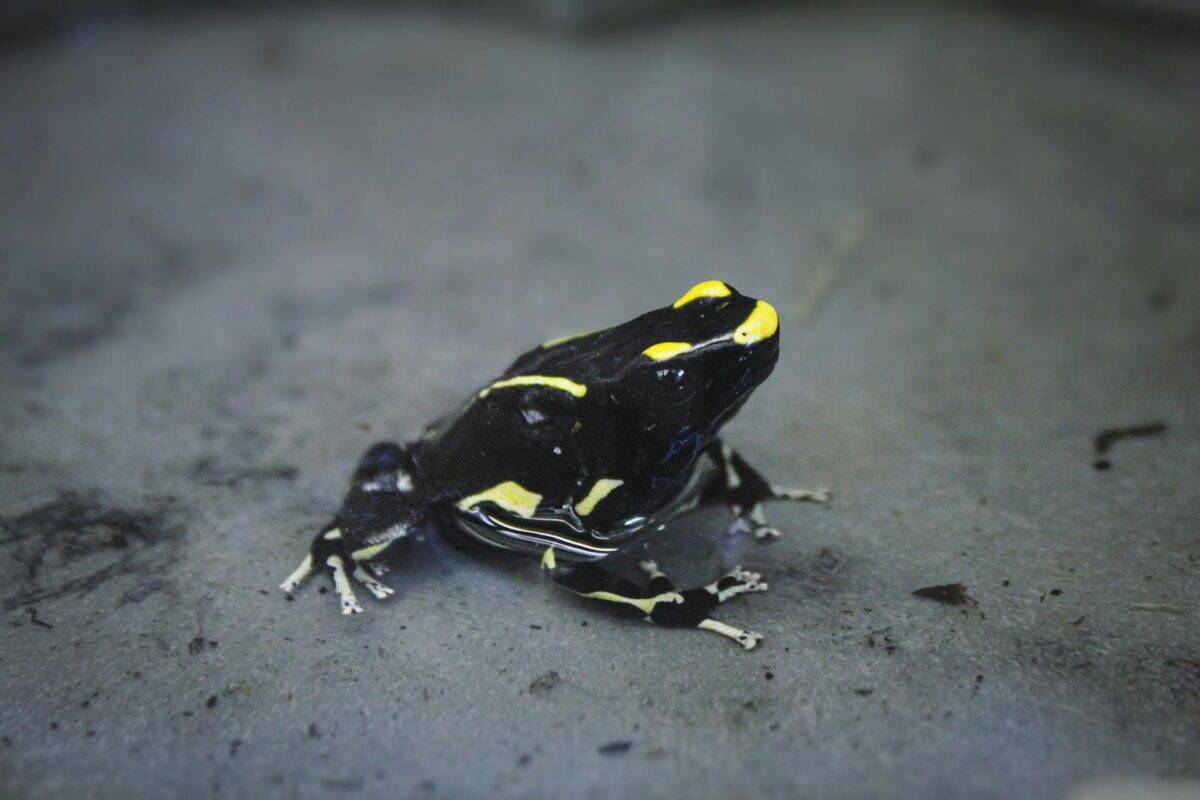

Amphibians: Canaries in the Coal Mine

Amphibians are among the most rainforest-dependent animal groups, with their permeable skin and complex life cycles making them particularly vulnerable to environmental changes. The poison dart frogs of Central and South American rainforests exemplify this dependency, with many species restricted to microhabitats as small as a single hillside. These frogs rely on specific rainforest plants to sequester the toxic compounds that make them poisonous and depend on the high humidity levels maintained by intact forest canopies. The spectacular golden poison frog contains enough toxin to kill 10 humans but can only produce these toxins when consuming specific rainforest insects. Similarly, the glass frogs of Neotropical rainforests have translucent skin and lay their eggs on leaves overhanging forest streams, requiring precise conditions of humidity, temperature, and water quality found only in pristine rainforests. Scientists consider amphibians “indicator species” whose health reflects overall ecosystem integrity, and their global decline—with rainforest species disappearing most rapidly—signals serious environmental deterioration. Research indicates that over 40% of amphibian species are currently threatened with extinction, with habitat loss in rainforests being a primary driver.

Birds of Paradise and Other Avian Specialists

Rainforests support extraordinary avian diversity, with many species evolving in isolation to become highly specialized for specific forest niches. The birds of paradise in New Guinea’s rainforests represent one of evolution’s most spectacular examples, with males developing elaborate plumage and complex courtship displays that depend on particular rainforest clearings and perches. These birds have co-evolved with specific rainforest fruits and display grounds, making them unable to adapt to other habitats. Similarly, the harpy eagle—one of the world’s largest and most powerful eagles—requires vast stretches of undisturbed rainforest to hunt monkeys and sloths in the canopy. With a wingspan reaching seven feet, these birds need large trees for nesting and raising their young, producing just one chick every two to three years. The helmeted hornbill of Southeast Asian rainforests depends on large fruiting trees and specific nesting cavities, while also requiring the unique social structure of intact rainforest bird communities. For these specialized birds, rainforest fragmentation can be devastating, as they often cannot cross gaps between forest patches, leading to isolated, genetically vulnerable populations. Studies show that even selective logging can reduce rainforest bird diversity by 50% or more by removing the specific trees these specialists require.

Insects: The Hidden Majority

While large animals often receive the most conservation attention, insects represent the vast majority of rainforest biodiversity and include many of the most habitat-dependent species. Scientists estimate that millions of insect species in rainforests remain undiscovered, with many likely restricted to single valleys or mountainsides. Butterfly species like the blue morpho have evolved complex relationships with specific rainforest plants, laying eggs only on particular species and depending on forest conditions for their complex life cycles. Leaf-cutter ants, which maintain underground fungus gardens, rely on specific rainforest leaf chemistry to cultivate their food source. These ants process up to 17% of the leaf production in Neotropical rainforests and create vital soil nutrients. The giant scarab beetles of Amazon and Congo Basin rainforests depend on the dung of large rainforest mammals to complete their life cycles, representing complex dependency chains. Beyond their intrinsic value, these insects provide critical ecosystem services including pollination, decomposition, and serving as food sources for larger animals. Research has demonstrated that rainforest insect biomass and diversity can decline by over 75% in areas affected by even moderate forest disturbance, with far-reaching consequences for the entire ecosystem.

Reptiles of the Rainforest

Rainforests host an incredible diversity of reptiles that have evolved specialized adaptations for life in these humid, complex environments. The emerald tree boa and green tree python represent a classic case of convergent evolution, developing nearly identical body forms and hunting strategies despite evolving independently in South American and Australian-Papuan rainforests, respectively. These arboreal specialists have heat-sensing pits to detect warm-blooded prey in the dark canopy and cannot survive outside intact forest habitats. Flying dragons (Draco species) of Southeast Asian rainforests have evolved modified ribs and skin flaps that allow them to glide up to 200 feet between trees, an adaptation that requires the specific vertical structure of rainforest canopies. The king cobra, the world’s longest venomous snake, inhabits Asian rainforests where it depends on high humidity levels and abundant prey consisting of other rainforest snakes. Similarly, the massive reticulated python requires the consistent temperatures and prey abundance found only in Southeast Asian rainforests to maintain its metabolic needs. These reptiles often have narrow temperature and humidity tolerances, making even subtle changes to rainforest microclimates potentially lethal. Research shows that reptile communities can collapse within years of forest fragmentation as their specialized microhabitats disappear.

Mammals of the Forest Floor

The rainforest floor hosts numerous mammal species that depend on the unique conditions created by the dense canopy above. The okapi, often called the forest giraffe, is found exclusively in the Ituri Rainforest of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where it uses its prehensile tongue to select specific rainforest leaves and its striped legs to blend with dappled forest light. Similarly, the tapirs of South American and Southeast Asian rainforests have specialized digestive systems adapted to process rainforest vegetation and play crucial roles in seed dispersal for hundreds of plant species. The forest elephant, smaller than its savanna cousin, has evolved specifically for navigating dense rainforests of Central Africa, creating vital clearings and trails that serve as habitat for other species. These forest elephants disperse seeds of over 300 rainforest tree species that cannot germinate without passing through their digestive tracts. The giant anteater depends on large, undisturbed rainforest territories to find sufficient termite and ant colonies, consuming up to 35,000 insects daily. These forest floor mammals often require expansive, connected rainforest territories and cannot adapt to fragmented or degraded habitats. Research indicates that even large rainforest mammals can disappear from forest fragments smaller than 25 square miles, highlighting the importance of preserving large, intact rainforest blocks.

Unique Canopy Specialists

The rainforest canopy hosts highly specialized animals found nowhere else on Earth, including mammals with remarkable adaptations for life among the treetops. Sloths represent perhaps the most extreme canopy specialists, with metabolisms so slow they descend to the ground only once weekly to defecate. Their fur hosts specialized algae that grows only in rainforest conditions, providing camouflage and supplemental nutrition. These slow-moving mammals are completely dependent on specific rainforest trees like cecropia for food and cannot survive outside intact forest canopies. Flying mammals like the Malaysian colugo have evolved specialized membranes stretching from neck to toes, allowing them to glide up to 230 feet between rainforest trees—an adaptation useless outside forest environments. Numerous bat species, including the tent-making bats of Central America, have co-evolved with specific rainforest plants, modifying leaves into protective tents and dispersing the seeds of over 500 rainforest plant species. The pygmy glider of Indonesian rainforests, weighing less than 100 grams, depends on the special properties of rainforest sap and nests exclusively in cavities of old-growth rainforest trees. These specialized canopy dwellers face particularly severe threats from selective logging, which often targets the largest trees first, eliminating their critical habitat while leaving the forest appearing largely intact from satellite monitoring.

Freshwater Species Dependent on Rainforests

While not always immediately associated with rainforests, countless aquatic species depend entirely on the unique waterways that flow through these ecosystems. The Amazon River dolphin (boto) navigates flooded rainforest during seasonal inundations, feeding on fish species that themselves rely on fruits and insects falling from rainforest vegetation. Studies show these dolphins can travel up to 30 kilometers into flooded forest during high-water seasons. Similarly, the Arapaima, one of the world’s largest freshwater fish, depends on the seasonal flooding of Amazon rainforest to reproduce and feed, with juveniles finding protection among submerged rainforest vegetation. The giant otter of South American rainforest rivers requires clear waters and abundant fish populations maintained by intact forest watersheds. In Southeast Asian rainforests, the rare and endangered Siamese crocodile depends on specific river conditions maintained by forest cover, including stable banks for nesting and water quality regulated by forest filtration. Research demonstrates that deforestation along rainforest waterways causes rapid sedimentation, temperature changes, and chemical alterations that eliminate these specialized aquatic species. For example, studies in Brazil have shown that fish diversity can decline by up to 95% in streams flowing through deforested areas compared to those in intact rainforest, highlighting how terrestrial forest protection directly impacts aquatic biodiversity.

Rainforest Invertebrates Beyond Insects

Beyond insects, rainforests host an astonishing array of other invertebrates that have evolved entirely within these ecosystems. The goliath bird-eating spider, the world’s largest spider by mass, inhabits burrows in the rainforest floor of South America, where it depends on the specific soil conditions and prey availability maintained by the forest ecosystem. Similarly, the giant earthworms of Ecuador’s cloud forests can reach lengths of over 5 feet and process forest soil in ways that maintain the unique chemical properties required by rainforest vegetation. Land snails show exceptional diversity in rainforests, with some areas of the Amazon basin containing over 100 species per square kilometer, many with shells adapted to camouflage among specific rainforest leaf litter. The giant African land snail, reaching lengths of 8 inches, depends on calcium-rich soils developed under specific rainforest vegetation. Leeches in Southeast Asian rainforests have evolved to detect mammal body heat and carbon dioxide at remarkable distances, allowing them to ambush passing rainforest mammals—a specialized hunting strategy requiring intact forest mammal communities. The extraordinary diversity of rainforest invertebrates remains largely uncatalogued, with scientists estimating that less than 10% have been formally described. These organisms often have extremely specific habitat requirements; studies show that even subtle changes to rainforest microclimates can eliminate entire invertebrate communities before they’re even discovered.

The Consequences of Rainforest Loss

The impacts of rainforest destruction extend far beyond the visible loss of trees, triggering complex cascade effects that eliminate dependent animal species. When rainforests are cleared or fragmented, the immediate consequences include the loss of physical habitat, but secondary effects often prove more devastating over time. Edge effects penetrate up to 1.5 kilometers into remaining forest fragments, altering temperature, humidity, and light conditions critical for specialized species. Research in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest demonstrates that fragments smaller than 250 acres lose up to 60% of their bird species within 15 years of isolation. Similarly, studies in Borneo show that orangutan populations cannot remain viable in forest patches smaller than 500 square kilometers. The disruption of ecological relationships proves particularly destructive, as the loss of key species creates ripple effects throughout the ecosystem. For example, when large fruit-eating animals disappear from rainforest fragments, the trees that depend on them for seed dispersal fail to reproduce, eventually leading to forest composition changes that eliminate habitat for dozens of other species. Climate feedback loops accelerate these processes, as deforestation reduces rainfall and increases local temperatures, potentially pushing rainforest ecosystems toward irreversible tipping points. Scientists estimate that the Amazon could reach a catastrophic dieback threshold if deforestation exceeds 20-25% of its original extent, threatening thousands of dependent animal species with extinction.

Conservation Strategies for Rainforest-Dependent Animals

Protecting the extraordinary diversity of rainforest-dependent animals requires multi-faceted conservation approaches that address both immediate threats and long-term sustainability challenges. Creating and maintaining large, connected protected areas represents the most effective strategy, as research consistently shows that rainforest reserves smaller than 10,000 hectares lose species over time. The Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project in Brazil has demonstrated that connecting isolated forest patches with corridors can maintain up to 90% of original mammal diversity, compared to just 60% in unconnected fragments of similar size. Indigenous land rights also correlate strongly with forest preservation, with satellite studies showing that indigenous territories experience deforestation rates 50-80% lower than surrounding unprotected forests. Market-based approaches like certification for sustainable rainforest products provide economic alternatives to destructive industries, with certified timber operations maintaining approximately 35% more biodiversity than conventional logging. Technological innovations in monitoring, including acoustic sensors that can detect poaching activity an

- How Animals Care for Their Sick and Injured - August 24, 2025

- 12 Animals You’ll Only See in the Tallest US Ranges - August 24, 2025

- How Filmmakers Capture Elusive Animals on Camera - August 24, 2025