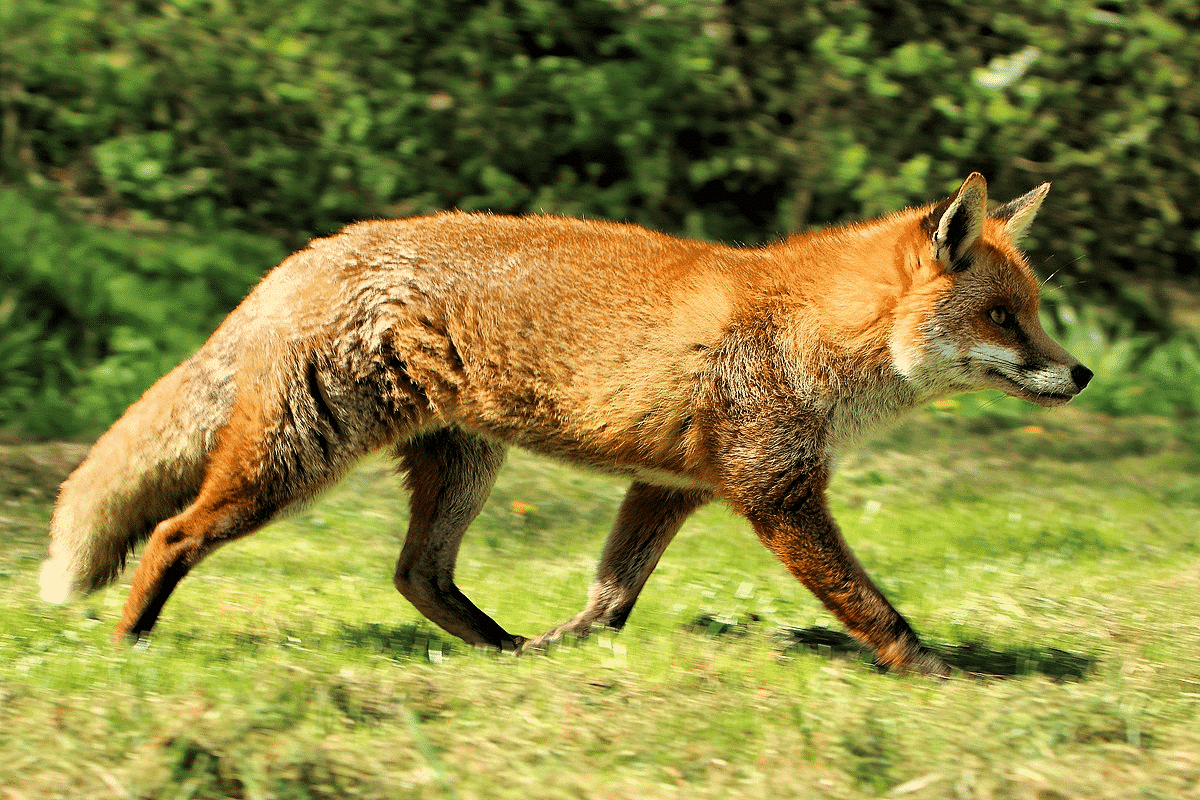

In the wilderness of animal relationships, foxes stand as fascinating creatures with complex social bonds and family structures. While many animals in the natural world form lifelong partnerships—like swans, wolves, and certain birds of prey—foxes follow a different pattern. This article delves into the intriguing mating behaviors of foxes, their family dynamics, and the evolutionary adaptations that have shaped their reproductive strategies. By understanding how these clever canids approach partnerships and raising young, we gain valuable insights into their survival techniques and social organization that has allowed them to thrive across diverse habitats worldwide.

The Mating Habits of Foxes: Seasonal Monogamy

Contrary to popular belief, foxes do not mate for life. Instead, they practice what biologists call “seasonal monogamy” or “serial monogamy.” Most fox species, including the widespread red fox (Vulpes vulpes), form pair bonds that typically last for a single breeding season. This mating pattern involves a male and female fox coming together during the winter breeding season, usually between December and February in the Northern Hemisphere.

During this time, the pair will remain exclusively committed to each other, hunting together, defending territory as a unit, and ultimately raising their young cooperatively. However, this bond rarely extends beyond a single breeding season. When the next mating season arrives, foxes often seek new partners, although in some cases, particularly when the previous partnership was successful, they may reunite with the same mate for another season.

The Courtship Dance: How Foxes Choose Their Mates

Fox courtship is a complex and fascinating ritual that begins several weeks before actual mating occurs. Males will often compete for the attention of females through various displays of strength, agility, and resource provision. During the breeding season, male foxes become more vocal, producing distinctive barking calls that advertise their presence to potential mates. They may also engage in playful chases and mock fights to demonstrate their fitness.

Female foxes select mates based on multiple factors, including physical condition, territory quality, and behavioral traits that suggest good parenting potential. Research has shown that females tend to prefer males who demonstrate hunting prowess and the ability to defend territory effectively. The courtship period allows both foxes to assess compatibility before committing to raising vulnerable offspring together, even if that commitment is relatively short-term compared to truly monogamous species.

Fox Family Formation: The Development of the Den

Once a fox pair has formed, they begin preparing for the arrival of their young by establishing or renovating a den. The female, known as a vixen, typically takes the lead in selecting the den site, often choosing locations with multiple entrances for safety. Den sites vary by habitat but commonly include hollow logs, rock crevices, abandoned burrows, or self-dug earthen tunnels. Urban foxes have adapted to use spaces beneath sheds, decks, or other human structures.

The den serves as the central hub of fox family life during the breeding season, providing protection for vulnerable kits (baby foxes) during their first weeks of life. A complex den system may feature several chambers and emergency exits to evade predators. The male fox, while not typically involved in den construction, helps protect the territory surrounding the den and brings food to the nursing mother during the early weeks after birth, demonstrating the cooperative nature of their seasonal partnership.

Birth and Early Development of Fox Kits

After a gestation period of approximately 52 days, the vixen gives birth to a litter averaging 4-5 kits, though litter sizes can range from 1-13 depending on species, food availability, and the mother’s health. Fox kits are born blind, deaf, and covered in short, dark fur that bears little resemblance to their adult coloration. They are entirely dependent on their mother for the first few weeks of life, relying on her milk and the warmth of the den to survive.

By three weeks of age, the kits’ eyes open, and they begin to develop more rapidly. Around four weeks, they start venturing outside the den under close supervision, and by eight weeks, they actively participate in play that develops crucial hunting and survival skills. Throughout this developmental period, both parents are typically involved in care, with the male bringing food while the female nurses and protects the young. This cooperative parenting strategy increases survival rates despite the seasonal nature of their pair bond.

The Role of the Male Fox in Family Life

Male foxes, unlike many other mammal species, play a significant role in raising their offspring. After the kits are born, the male (called a dog fox or reynard) takes on primary hunting responsibilities, bringing food to the nursing mother who remains with the kits in the den. This provisioning is crucial, as the female’s nutritional needs increase dramatically while nursing multiple rapidly growing kits.

As the kits grow older, the male fox continues his parental duties by helping to teach hunting skills and territorial defense. Research has shown that male foxes can recognize their offspring and show preferential treatment toward them. This investment in offspring is likely an evolutionary adaptation that improves survival rates in species where raising young requires significant resources and protection. However, this devoted parenting doesn’t necessarily translate to lifelong bonding with the mother, as the partnership usually dissolves after the young reach independence.

Fox Family Dynamics: The Importance of Extended Family

While the core fox family unit consists of the breeding pair and their offspring, fox family structures can sometimes be more complex. In certain circumstances, particularly when resources are abundant, red fox families may include “helpers” – typically female offspring from the previous year who remain with their parents. These helpers, sometimes called alloparents, assist with den maintenance, territorial defense, and even kit care, though they don’t reproduce themselves during this time.

This expanded family structure, observed more frequently in some fox species than others, represents a fascinating evolutionary strategy. For the young helpers, remaining with parents provides additional time to learn survival skills before establishing their own territories. For the breeding pair, the assistance increases the chances of successfully raising the current litter. While not as complex as wolf pack structures, these extended fox families demonstrate that fox social dynamics can be more sophisticated than the simple seasonal pair bond might suggest.

Different Mating Systems Across Fox Species

While seasonal monogamy is the predominant mating system among foxes, the 37 species in the fox family (Canidae) show interesting variations. The Arctic fox (Vulpes lagopus), for instance, forms particularly strong pair bonds that sometimes last multiple seasons, likely an adaptation to the harsh Arctic environment where cooperative hunting and parenting significantly increase survival chances. These bonds still don’t constitute true lifelong monogamy but represent a stronger version of serial monogamy.

By contrast, the bat-eared fox (Otocyon megalotis) of Africa often forms more enduring partnerships, with some pairs remaining together for multiple consecutive breeding seasons. Males in this species are exceptionally involved in parenting, sometimes spending more time with cubs than females do. These variations in mating systems across fox species demonstrate how reproductive strategies evolve to match particular ecological niches and environmental challenges, rather than following a single pattern across all fox species.

The Dispersal Phase: When Young Foxes Leave Home

As autumn approaches, approximately 6-7 months after birth, young foxes begin the dispersal phase—leaving their birth territory to establish their own range. This period represents the dissolution of the family unit that has remained intact since birth. Typically, juvenile foxes travel between 5 and 25 miles from their birth den, though some may disperse much further distances of 50 miles or more. Male foxes generally disperse farther than females, reducing the chances of inbreeding when they begin to reproduce.

This dispersal period is particularly dangerous for young foxes, with mortality rates reaching up to 80% in some populations during their first year. They face challenges including territorial aggression from established foxes, predation, vehicle collisions, and food scarcity. Those that survive this critical period will establish their own territories and, when the breeding season arrives, begin the cycle anew. The seasonal nature of fox pair bonds means that parents and offspring rarely maintain relationships after this dispersal, unlike some more socially complex mammals.

Urban Foxes: Adaptations in Mating Behavior

Urban fox populations, which have thrived in cities worldwide, show fascinating adaptations in their mating and family structures compared to their rural counterparts. Research, particularly from cities like London with well-studied fox populations, indicates that urban foxes tend to maintain smaller territories due to concentrated food resources. This territorial compression sometimes leads to more stable pair bonds that may last multiple breeding seasons, as the need to seek new territories is reduced.

Urban environments also affect fox family structure through changes in mortality patterns. While rural foxes face significant predation and hunting pressure, urban foxes more commonly encounter vehicle collisions and disease. In some urban areas, researchers have documented extended family groups where offspring remain in parental territories longer, creating more complex social units than typically seen in rural settings. These adaptations demonstrate the remarkable flexibility of fox mating systems in response to environmental conditions.

The Evolutionary Advantages of Seasonal Monogamy

The seasonal monogamy practiced by foxes represents an evolutionary middle ground between true lifelong monogamy and promiscuous mating systems. This strategy offers several advantages for survival and reproductive success. By forming pair bonds during the breeding and kit-raising period, foxes ensure that vulnerable offspring receive care from both parents, significantly increasing survival rates in environments where single-parent rearing would be challenging.

However, the flexibility to form new pair bonds each season allows foxes to adapt to changing environmental conditions and partner availability. If a previous mate has died or the territory quality has declined, foxes can seek more advantageous partnerships. This adaptability may partially explain why foxes have successfully colonized diverse habitats across multiple continents. The seasonal monogamy system balances the benefits of cooperative parenting with the advantages of genetic diversity and environmental adaptability that come with changing partners.

Common Misconceptions About Fox Relationships

Popular culture often romanticizes animal relationships, leading to widespread misconceptions about fox mating habits. The notion that foxes mate for life likely stems from confusion with other canids like wolves, which form more enduring pack structures, or from anthropomorphizing their visible pair bonding during the breeding season. While a fox pair may appear deeply bonded while raising their young, the biological reality is that this bond is typically temporary and pragmatic rather than emotional in the human sense.

Another common misconception is that fox “families” remain together long-term. In reality, the family unit disperses naturally as young reach maturity, with parents often seeking different mates in subsequent seasons. Understanding these natural behaviors helps foster more accurate conservation approaches and reduces inappropriate interventions based on misunderstandings of normal fox social dynamics. Appreciating foxes for their actual mating strategies, rather than imposing human relationship ideals, allows for a more authentic connection with these remarkable adaptable predators.

Conclusion: The Adaptive Family Life of Foxes

Foxes demonstrate that successful family structures in nature don’t necessarily follow human ideals of lifelong partnership. Their seasonal monogamy represents a finely-tuned evolutionary response to the challenges of survival and reproduction in varied environments. The fox’s ability to form strong, cooperative partnerships for raising young, while maintaining the flexibility to adapt to changing conditions through new pair bonds each season, has contributed significantly to their success as a species across diverse habitats worldwide.

Understanding the true nature of fox family dynamics enhances our appreciation for the sophistication of their social behaviors and the evolutionary processes that shaped them. While they don’t mate for life in the romantic sense that humans might imagine, the seasonal dedication they show to their partners and offspring represents its own form of remarkable commitment. Their family structure reminds us that in nature, successful relationship patterns are those that best serve survival and adaptation, taking many forms beyond the narrow constraints of human expectations.

As we continue to share landscapes with these adaptable canids, recognizing the reality of their social structures helps inform conservation efforts and human-wildlife interactions. The fox’s pragmatic approach to partnership offers a window into the fascinating diversity of reproductive strategies in the animal kingdom, where the measure of success is not the permanence of bonds but their effectiveness in ensuring the continuation of life.

- How Penguins Take Turns at Sea and Nest to Raise Chicks - August 9, 2025

- Dolphin Brains Compare to Those of Apes and Humans - August 9, 2025

- 14 Cutting-Edge Biotech Innovations That Will Shape the Future - August 9, 2025