The Pacific Ocean, encompassing over 60 million square miles of our planet, is home to some of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth. While many are familiar with endangered icons like the sea turtle or blue whale, countless lesser-known species face extinction across this vast region. From the depths of coral reefs to remote island forests, these animals and plants fight a silent battle against habitat loss, climate change, invasive species, and human exploitation. This article explores twelve remarkable endangered Pacific species that deserve our attention and conservation efforts, despite flying under the radar of public awareness. Their stories highlight both the incredible diversity of the Pacific realm and the urgent challenges that threaten the region’s unique natural heritage.

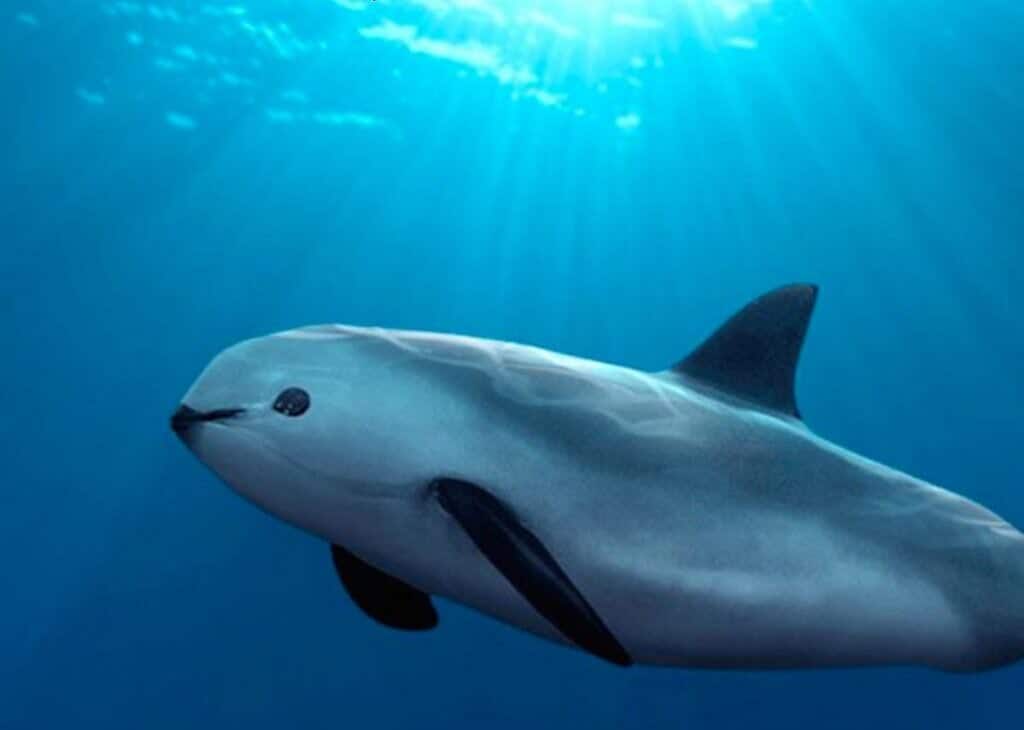

The Vaquita: World’s Most Endangered Marine Mammal

With fewer than 10 individuals remaining in the wild, the vaquita (Phocoena sinus) holds the unfortunate distinction of being the most endangered marine mammal on Earth. Native to the northern Gulf of California in the Pacific Ocean, these small porpoises measure just 5 feet in length and have distinctive dark rings around their eyes. Despite never being directly hunted, vaquitas have been decimated by becoming entangled in gillnets set for other species, particularly the totoaba, whose swim bladders fetch high prices in black markets. Conservation efforts have included a gillnet ban throughout their range and attempts at captive breeding, but the population continues to decline at an alarming rate. Without immediate and effective intervention, the vaquita will likely become the second cetacean species driven to extinction by human activities in the 21st century.

Hawaiian Monk Seal: The Islands’ Only Native Seal

The Hawaiian monk seal (Neomonachus schauinslandi) represents one of the most endangered seal species globally, with approximately 1,400 individuals remaining. Endemic to the Hawaiian archipelago, these seals once thrived across the entire island chain but are now primarily confined to the remote Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. They face numerous threats including limited food availability, entanglement in marine debris, predation on pups by sharks, male aggression, and disease. Distinguished by their gray-brown coloration and relatively small size compared to other seals, they can reach 7 feet in length and weigh up to 600 pounds. Conservation efforts include habitat protection, rehabilitation of injured seals, and translocating vulnerable pups to safer locations. The Hawaiian name for these seals, “Ilio-holo-i-ka-uaua” (dog running in rough water), reflects their cultural significance to native Hawaiians, making their protection both an ecological and cultural imperative.

Kakapo: The Flightless Parrot of New Zealand

The kakapo (Strigops habroptilus) is perhaps one of the most unusual birds in the Pacific region—a flightless, nocturnal parrot found only in New Zealand. With just over 200 individuals surviving today, this moss-green bird represents one of the world’s rarest avian species. Weighing up to 9 pounds, the kakapo is the heaviest parrot in the world and can live for more than 90 years. Its decline began with Polynesian settlement of New Zealand and accelerated following European colonization, which introduced predators like cats, rats, and stoats to which the ground-dwelling birds had no defense. The kakapo’s unusual breeding system compounds conservation challenges—males gather at display grounds (leks) and boom to attract females, but they only breed every 2-4 years when certain native trees produce abundant fruit. Today, conservation efforts include intensive predator control, supplementary feeding, artificial insemination, and maintaining all surviving birds on predator-free island sanctuaries. Each kakapo has a name and receives individual monitoring with radio transmitters, making this one of the most personalized conservation programs in the world.

Omura’s Whale: The Recently Discovered Giant

Omura’s whale (Balaenoptera omurai) represents one of the most enigmatic endangered species in the Pacific. Only scientifically described in 2003 and first documented alive in the wild in 2015, this baleen whale was previously misidentified as a smaller version of Bryde’s whale. Reaching lengths of up to 33 feet, Omura’s whales feature distinctive asymmetrical coloration—their right jaw is white while the left is dark. Their range appears to include tropical and subtropical waters across the Pacific and Indian Oceans, with confirmed populations off Madagascar, Sri Lanka, and in the Timor Sea. The species likely numbers in the hundreds or low thousands, though accurate population estimates remain difficult due to limited sightings and research. While protected by international whaling moratoriums, these whales face threats from ship strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, and acoustic pollution. The late discovery of such a large mammal species underscores how much remains unknown about Pacific marine biodiversity and raises concerns about what might be lost before it can even be documented.

Mary River Turtle: The Punk Rocker of Queensland

The Mary River turtle (Elusor macrurus) of eastern Australia has earned internet fame for its punk-rock appearance—some individuals grow algae on their heads, giving them a green mohawk-like appearance. Beyond this striking feature, these remarkable reptiles can breathe through specialized glands in their cloaca, allowing them to remain underwater for up to three days. Endemic to the Mary River in Queensland, these turtles were once collected in massive numbers for the pet trade before scientists formally described them in 1994. By then, their population had already crashed. Now critically endangered, the Mary River turtle faces ongoing threats from water quality degradation, introduced predators that target their eggs, and habitat alteration from dam construction and agricultural development. With females not reaching sexual maturity until 25 years of age and limited to a single river system, their recovery requires long-term commitment. Conservation efforts include nest protection, captive breeding, and habitat restoration, though their population is estimated at fewer than 10,000 mature individuals.

Lord Howe Island Stick Insect: Back from the Dead

Sometimes called the “tree lobster,” the Lord Howe Island stick insect (Dryococelus australis) represents one of the most remarkable comeback stories in conservation. Native to Lord Howe Island in the Tasman Sea, these massive insects—reaching nearly 6 inches in length—were thought extinct after black rats accidentally introduced in 1918 decimated the population. For decades, these insects were mourned as lost until 2001, when researchers discovered a tiny population of fewer than 30 individuals surviving on Ball’s Pyramid, a remote sea stack about 14 miles from Lord Howe Island. This precipitous volcanic remnant, rising 1,844 feet from the ocean, somehow harbored enough vegetation to support these giant insects in what may be the most restricted habitat of any insect species. Conservation efforts have established successful breeding programs at several zoos, with plans to reintroduce the species to Lord Howe Island following intensive rat eradication efforts. Their story demonstrates both the devastating impact of invasive species and the remarkable resilience of nature when given even the slimmest chance of survival.

Okinawa Spiny Rat: Japan’s Forest Phantom

The Okinawa spiny rat (Tokudaia muenninki) represents one of the world’s rarest and most genetically unusual rodents. Endemic to Okinawa Island in the Ryukyu Archipelago of Japan, this critically endangered mammal was thought extinct until rediscovered in 2008. What makes this species particularly fascinating to scientists is its unusual chromosomal arrangement—it has completely lost its Y chromosome during evolution, a rare phenomenon among mammals. Despite its name, the Okinawa spiny rat is not particularly spiny compared to related species and measures about 8 inches in length including its tail. Its population has been devastated by habitat loss, with Okinawa’s native forests reduced to just 10% of their original extent due to agricultural expansion, urbanization, and military base construction. Additionally, introduced mongooses, feral cats, and invasive black rats have further pressured the species. Conservation efforts focus on habitat protection in northern Okinawa’s remaining forests, predator control programs, and research to understand their unusual genetic characteristics and reproductive biology.

Devils Hole Pupfish: Surviving in a Desert Cavern

Perhaps occupying the smallest natural range of any vertebrate species, the Devils Hole pupfish (Cyprinodon diabolis) lives exclusively in a single water-filled cavern in the Nevada desert, part of the greater Pacific drainage basin. These tiny iridescent blue fish, barely an inch long, survive in what should be impossible conditions—a constant 93°F water temperature, low oxygen levels, and limited food resources. Their entire natural habitat consists of a limestone cavern with a surface area of just 538 square feet, though they primarily occupy a shallow shelf measuring only 6.5 by 13 feet. Despite surviving in this location for an estimated 10,000 years, the population has never been large, fluctuating between 35-315 individuals in recent decades and dropping as low as 35 fish in 2013. Threats include groundwater pumping that affects water levels, accidental or intentional human intrusion, and natural disasters. Conservation efforts include maintaining a backup population in artificial habitats, careful monitoring of water quality and levels, and legal protection of the groundwater system. Their extraordinary adaptation to such extreme conditions makes them invaluable for scientific research on evolution and survival in marginal environments.

Giant Palouse Earthworm: America’s Vanishing Giant

The Pacific Northwest’s Giant Palouse earthworm (Driloleirus americanus) represents one of the most elusive endangered species in North America. Native to the Palouse prairie region spanning Washington and Idaho, these remarkable invertebrates were once thought to reach three feet in length, though modern specimens typically measure about a foot long. Their distinctive characteristics include a lily-like scent when handled, pale white coloration, and the ability to spit at predators. Originally discovered in 1897, these earthworms became so rare that between 1978 and 2010, only four specimens were confirmed, leading many to fear their extinction. Their decline correlates directly with the conversion of native Palouse prairie to agriculture—less than 1% of this ecosystem remains intact. Besides habitat loss, they face threats from invasive earthworm species, chemical fertilizers, and soil compaction. Despite their ecological importance in creating soil channels that enhance water penetration and root growth, conservation efforts remain limited. Currently, they have no federal protection status despite petitions for endangered species listing. Recent genetic studies and the development of eDNA sampling techniques offer hope for better understanding their distribution and remaining population.

Amami Rabbit: Living Fossil of the Ryukyu Islands

The Amami rabbit (Pentalagus furnessi) represents an evolutionary marvel, often described as a “living fossil” due to its primitive characteristics that resemble ancient rabbit ancestors. Endemic to just two small Japanese islands in the Ryukyu Archipelago—Amami Ōshima and Toku-no-Shima—these endangered rabbits have evolved in isolation for millions of years. Distinctly different from typical rabbits, they feature small ears, short legs, dark brown fur, and prominent curved claws adapted for digging. They’re nocturnal, solitary, and unlike most rabbits, females care for only one or two young at a time in underground burrows. With a total population estimated at fewer than 5,000 individuals, they face multiple threats including predation by introduced mongooses (ironically brought to the islands to control venomous snakes), habitat fragmentation from logging and road construction, and occasional mortality from vehicular collisions. Conservation efforts include mongoose trapping programs that have reduced predator numbers, habitat protection through the establishment of the Amami Gunto National Park in 2017, and ongoing research and monitoring. As a cultural icon in the Ryukyu Islands, their image appears in local art, tourism materials, and even as a mascot for conservation initiatives.

Fiji Crested Iguana: The Jewel of South Pacific Reptiles

The Fiji crested iguana (Brachylophus vitiensis) stands among the most visually striking endangered reptiles in the Pacific, with its emerald green coloration accented by white or blue bands and distinctive crests along its back. First discovered by scientists in 1979 when one appeared in a film shot on Fiji’s Yadua Taba Island, these iguanas are endemic to a handful of Fijian islands but have disappeared from most of their historic range. Currently, fewer than 5,000 mature individuals survive, with the majority confined to a 70-hectare wildlife sanctuary on Yadua Taba. Their decline stems primarily from habitat destruction, with Fiji’s dry tropical forests—their preferred habitat—reduced to less than 1% of their original extent due to agricultural clearing, tourism development, and fire. Additionally, introduced predators including cats, mongooses, and rats prey on juveniles and eggs, while goats degrade forest quality by consuming native plants. Conservation efforts include strict protection of Yadua Taba as a sanctuary, captive breeding programs at several international zoos, and forest restoration projects. Recent research shows that these iguanas play a vital ecological role as seed dispersers for native plants, making their conservation essential for the broader forest ecosystem.

The endangered species profiled here represent just a fraction of the Pacific’s biodiversity crisis, offering glimpses into ecosystems under unprecedented threat. Each species tells a story of survival against mounting odds—whether adapting to extreme conditions like the Devils Hole pupfish or persisting in tiny fragments of once-vast habitats like the Giant Palouse earthworm. Their struggles reflect larger patterns of environmental degradation across the Pacific region, where island ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to invasive species, habitat destruction, and climate change impacts. Conservation success stories like the Lord Howe Island stick insect demonstrate that even species on the brink can recover with dedicated intervention, while ongoing declines of the vaquita remind us that knowledge alone does not ensure survival without effective protection measures. As we face a global biodiversity crisis, these lesser-known species deserve both our attention and our action, serving as ambassadors for countless other Pacific species facing extinction without ever entering public awareness.

- 10 Record-Breaking Animals That Hold the Title for Biggest, Fastest, and Strongest - August 15, 2025

- What Makes Pufferfish Inflate? - August 15, 2025

- Meet the Bee Hummingbird: The Smallest Bird Alive - August 15, 2025