When we consider the intricate world of animal behavior, one of the most fundamental and fascinating aspects is nursing—the process by which mother animals nourish their young. This behavior, while seemingly straightforward, varies dramatically across species and reveals remarkable adaptations that have evolved over millions of years. From mammals that produce nutrient-rich milk to birds that regurgitate food for their chicks, the animal kingdom displays an astonishing diversity of nursing behaviors that ensure the survival of offspring. These behaviors not only provide essential nutrition but also foster crucial bonds between parents and young, teaching important survival skills and establishing social hierarchies that can last a lifetime. In this comprehensive exploration, we’ll journey through the fascinating world of nursing behaviors across different animal groups, uncovering the evolutionary significance, unique adaptations, and extraordinary parental investment that characterizes these essential interactions.

The Evolutionary Significance of Nursing

Nursing behaviors represent one of the most significant evolutionary adaptations in the animal kingdom. The ability to provide nutrition directly to offspring has allowed countless species to increase their reproductive success by improving offspring survival rates. For mammals, the evolution of mammary glands approximately 200-300 million years ago marked a revolutionary advancement that defined an entire class of animals. This adaptation allowed young to receive perfect nutrition while remaining protected from predators and environmental challenges during their most vulnerable developmental stages. The evolutionary investment in nursing behavior demonstrates a trade-off between current parental energy expenditure and future reproductive potential, ultimately favoring species that developed effective nursing strategies. From an evolutionary standpoint, nursing represents an exceptional example of parental investment theory, where resources allocated to current offspring improve their chances of survival and eventual reproductive success, thereby passing on the parent’s genes to future generations.

Mammalian Milk Production: Nature’s Perfect Food

The hallmark of mammalian nursing is the production of milk, a remarkably complex biological fluid designed to provide complete nutrition to growing offspring. Mammalian milk contains an ideal blend of proteins, fats, carbohydrates, vitamins, minerals, and bioactive compounds specifically tailored to the needs of each species. Human milk, for instance, contains approximately 3-5% fat, 1% protein, and 7% lactose, along with hundreds of distinct bioactive molecules that support immune development. By contrast, seal milk contains up to 50% fat, enabling rapid growth in cold environments. Milk composition isn’t static—it changes dynamically throughout the nursing period to match the developing needs of offspring. The first milk produced after birth, colostrum, is particularly rich in antibodies and growth factors that provide essential immune protection. The mammary gland itself represents an evolutionary marvel, capable of converting maternal blood components into a completely different nutritional fluid through specialized epithelial cells. This biological factory operates continuously in nursing mothers, representing one of the most energetically demanding processes in nature, requiring up to 500 additional calories daily in humans and proportionally more in other mammals.

Nursing Durations and Weaning Strategies

The length of time mothers nurse their young varies dramatically across species, reflecting different evolutionary strategies and ecological pressures. Marine mammals like blue whales nurse for 6-7 months, delivering milk with approximately 40% fat content that allows calves to gain up to 90 kg per day. In contrast, orangutans have one of the longest nursing periods of any mammal, with young continuing to nurse for 6-8 years—a strategy that ensures the transmission of complex foraging skills in their challenging rainforest environment. The weaning process itself represents a period of significant behavioral negotiation between parent and offspring, with strategies ranging from gradual reduction in nursing frequency to abrupt termination. In many species, mothers employ tactics such as increasing rejection of nursing attempts, developing less palatable milk, or physically separating from offspring to encourage independence. These weaning conflicts illustrate the evolutionary tension between maternal investment and offspring demands. For social species, weaning often coincides with the development of peer relationships and integration into broader social groups, marking a critical transition in development. The timing of weaning represents a delicate balance between maximizing current offspring survival and preserving maternal resources for future reproductive opportunities.

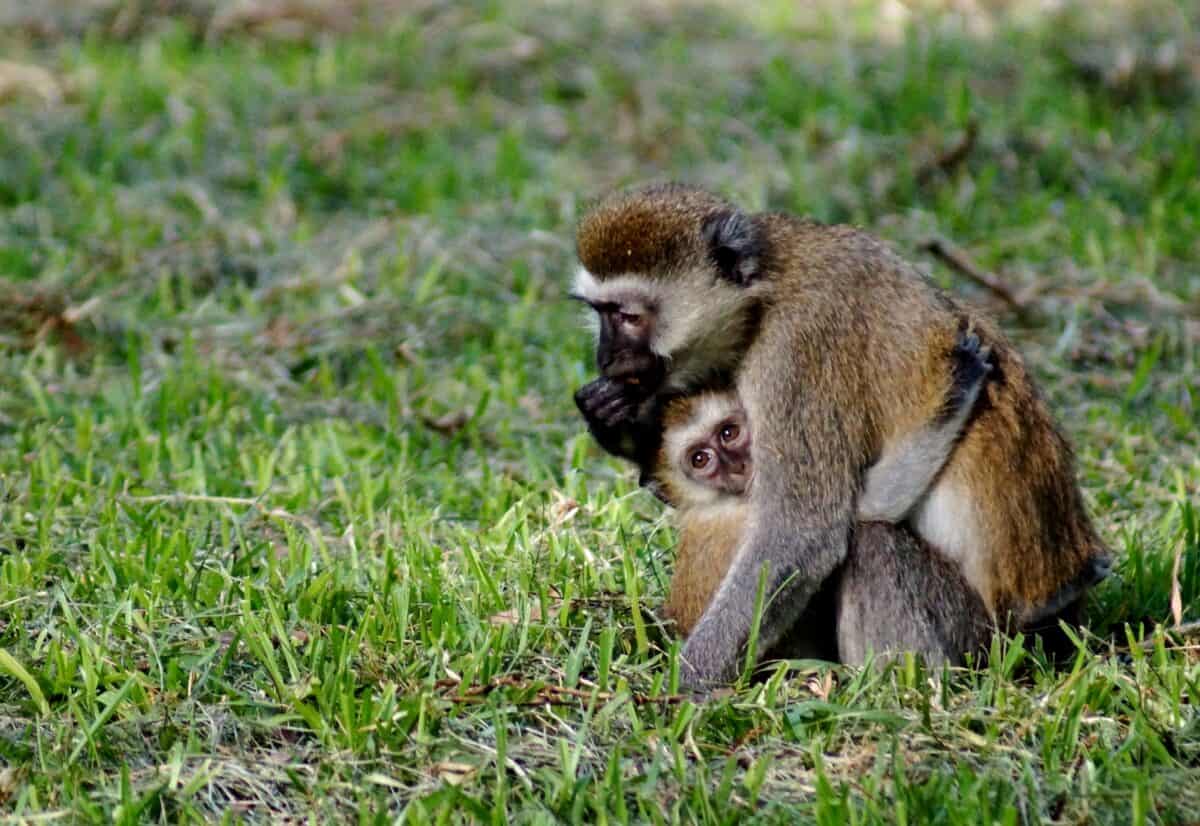

Communal Nursing and Alloparenting

While we often envision nursing as an exclusive relationship between mother and offspring, numerous species engage in communal nursing—a fascinating behavior where females nurse young that are not their own. In African elephants, “allomothers” assist with nursing duties, with younger female relatives often producing milk even before having their own calves. Lions in a pride will nurse each other’s cubs, creating a communal nursery that ensures offspring receive nutrition even if their mother is hunting or injured. This cooperative breeding strategy offers numerous advantages, including increased offspring survival, predator protection, and the distribution of energetic costs across multiple adults. In some bat colonies, females form nursing clusters where thousands of mothers can recognize and nurse their own pups despite seemingly impossible odds—identifying their specific offspring among millions through unique vocalizations and scent signatures. The evolution of communal nursing behavior appears most common in species facing harsh environmental conditions or predation pressure, where collective care improves overall reproductive success of the group. Interestingly, the hormone oxytocin plays a crucial role in facilitating these cooperative behaviors, promoting milk letdown not only for biological offspring but also triggering nurturing responses toward non-related young.

Bird Feeding Behaviors: A Different Form of Nursing

While birds lack mammary glands, they exhibit remarkable “nursing” behaviors through specialized feeding adaptations. Perhaps most extraordinary is the production of “crop milk” in pigeons, doves, and flamingos—a nutrient-rich secretion produced in the crop (a specialized part of the digestive tract) that parents regurgitate to feed their nestlings. This avian “milk” contains protein levels comparable to mammalian milk (approximately 13-19% protein) and is rich in fat, antibodies, and growth factors. Both male and female pigeons produce crop milk, making them among the few male animals capable of “nursing” their young. The hormone prolactin—the same hormone that stimulates milk production in mammals—triggers crop milk production, highlighting the evolutionary convergence of nursing behaviors. Beyond crop milk, birds employ diverse feeding strategies: passerine birds (songbirds) collect insects and regurgitate them in partially digested form; seabirds like albatrosses can fly hundreds of miles to gather fish, storing them in their crop before returning to feed chicks; and parent eagles tear prey into manageable pieces precisely matched to their eaglets’ developmental stage. These feeding behaviors represent a form of nursing adaptation that, while different from mammalian strategies, achieves the same essential goal of delivering optimized nutrition directly to offspring.

Marsupial Pouch Nursing: A Unique Adaptation

Marsupials such as kangaroos, koalas, and opossums have evolved one of the most distinctive nursing systems in the animal kingdom. Unlike placental mammals that develop their young internally until birth, marsupials give birth to extremely underdeveloped offspring—a newborn kangaroo is typically the size of a jelly bean, weighing less than 1 gram. These newborns immediately crawl into their mother’s pouch, where they attach to a nipple and remain for months during continued development. The marsupial pouch creates a protected external womb where sophisticated nursing occurs. Remarkably, marsupial mothers can simultaneously produce different milk formulations from adjacent nipples, tailored to the needs of joeys at different developmental stages. For example, a red kangaroo can produce high-protein milk for a newborn joey attached to one nipple while producing higher-fat, lower-protein milk for an older joey nursing from another nipple. This extraordinary adaptation allows efficient reproductive overlap, as mothers can support both a newborn and an older juvenile simultaneously. The pouch environment itself provides temperature regulation, protection, and a sterile environment during this critical developmental period. Some species, like the tammar wallaby, even have antiseptic compounds in their pouch secretions that protect the vulnerable young from infection—a comprehensive nursing system that extends well beyond nutrition alone.

Monotreme Nursing: Milk Without Nipples

Monotremes—egg-laying mammals including the platypus and echidnas—represent an evolutionary bridge between reptiles and mammals, exhibiting perhaps the most ancient form of mammalian nursing. These remarkable animals produce milk but lack nipples entirely. Instead, specialized mammary gland patches on the mother’s abdomen secrete milk directly onto their fur, which pools in grooves or depressions where the young can lap it up. Echidna babies (called puggles) develop in a temporary pouch-like fold of the mother’s abdomen, where they consume milk that seeps from these specialized patches. Platypus hatchlings similarly obtain milk from fur patches while in their burrow nests. Monotreme milk contains unique antimicrobial proteins not found in other mammalian milk, including novel antibacterial compounds that scientists are studying for potential medical applications. The composition of monotreme milk changes dramatically throughout the nursing period, with protein content increasing from 1.5% to 4% and fat content rising from 3.7% to 8.1% as the young develop. This nursing behavior, evolved approximately 166 million years ago, provides a fascinating glimpse into the earliest mammalian adaptations for offspring nourishment and represents a critical evolutionary step between reptilian parental care and more advanced mammalian nursing strategies.

Insect “Nursing” Behaviors

While insects lack mammary glands, several species have evolved nursing-like behaviors that parallel mammalian care. Perhaps most remarkably, certain cockroach species, such as the Pacific beetle cockroach (Diploptera punctata), have developed a form of “milk” production. The mother cockroach produces protein crystals in her brood sac that nourish developing embryos—these crystals contain proteins, fats, and sugars in a complete nutritional package that researchers have found to be among the most nutritionally dense substances on Earth. Social insects like ants, bees, and termites engage in trophallaxis—the direct mouth-to-mouth or mouth-to-anus transfer of regurgitated food—to feed larvae and other colony members. In some ant species, specialized “nurse workers” consume protein-rich foods and convert them into a nutrient-rich fluid they regurgitate to feed developing larvae. Burying beetles (Nicrophorus) prepare small animal carcasses as “nursing galleries” where they deposit their offspring, then feed them regurgitated, partially digested carrion directly from their mouthparts—a behavior remarkably similar to bird feeding. Female earwigs demonstrate exceptional maternal care, cleaning and tending their eggs, then regurgitating food for their nymphs after hatching. These insect nursing behaviors, while mechanistically different from mammalian nursing, demonstrate the convergent evolution of parental feeding strategies across dramatically different taxonomic groups, highlighting how similar selective pressures can produce analogous behaviors across the animal kingdom.

Amphibian and Fish Parental Feeding

While amphibians and fish typically don’t nurse in the traditional sense, several species have evolved extraordinary parental feeding mechanisms that parallel nursing behaviors. The gastric-brooding frogs of Australia (now extinct) practiced one of the most unusual feeding behaviors ever documented—mothers would swallow their fertilized eggs, convert their stomach into a brood chamber by ceasing acid production, then give birth through their mouths to fully formed froglets. During this period, the developing tadpoles received nourishment from secretions in the mother’s stomach lining. Similarly, the male Darwin’s frog incubates eggs in his vocal sac, providing nutrition to developing tadpoles through specialized secretions. Among fish, discus cichlids produce a mucus coating on their bodies that contains antibodies, growth factors, and nutrients—their fry feed directly on this mucus during their first weeks of life, effectively “nursing” from their parents’ skin. Male seahorses, famous for their pregnancy, not only carry developing embryos but also provide them with prolactin—the same hormone involved in mammalian milk production—which regulates the embryonic environment and provides essential nutrients. The female Surinam toad embeds fertilized eggs into specialized pockets on her back, where developing tadpoles receive nutrients through a placenta-like connection. These examples demonstrate how parental feeding adaptations have evolved independently across vertebrate lineages, achieving similar functional outcomes through dramatically different mechanisms.

The Neurobiological Basis of Nursing Behaviors

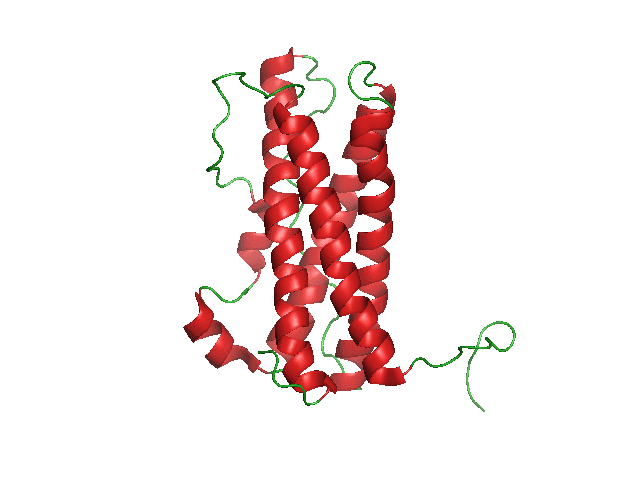

The initiation and maintenance of nursing behaviors across animal species is orchestrated by a sophisticated neuroendocrine system that has been remarkably conserved throughout evolution. The hormones prolactin and oxytocin (or their non-mammalian equivalents) play central roles in this process. Prolactin, produced in the pituitary gland, stimulates milk production in mammals, crop milk in birds, and nutrient-rich secretions in various other species. Research has shown that prolactin levels can increase by up to 20 times normal levels during peak lactation in mammals. Oxytocin, sometimes called the “bonding hormone,” triggers milk ejection and facilitates the emotional bond between mother and offspring. Brain imaging studies in mammals have revealed that nursing activates regions associated with reward processing, particularly the ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens—the same neural pathways involved in addiction—effectively “rewarding” mothers for nursing behavior. The hypothalamus serves as the command center for these processes, integrating sensory input (such as offspring cries or suckling stimulation) with hormonal signals to coordinate appropriate maternal responses. Remarkably, similar neurobiological mechanisms appear across diverse species; for instance, the hormone mesotocin (the avian equivalent of oxytocin) regulates crop milk production and parental behavior in birds. This neurobiological conservation suggests that nature found an effective solution for promoting parental care and has maintained these mechanisms across widely divergent evolutionary paths.

Nursing Behaviors and Social Learning

Nursing interactions provide far more than nutrition—they serve as critical contexts for social learning and the transmission of behavioral traditions. In species with complex foraging requirements, nursing sessions gradually transition to opportunities for offspring to learn about appropriate food sources. For example, young rats develop food preferences based on flavors experienced in their mother’s milk, effectively learning what foods are safe through nursing. Chimpanzee infants observe their mothers’ termite fishing techniques while nursing, eventually mimicking these complex tool-using behaviors. Killer whale calves spend up to two years nursing while simultaneously learning pod-specific hunting strategies and vocalizations that constitute a form of cultural knowledge. The close physical contact during nursing facilitates observational learning, with eye-tracking studies showing that nursing infants spend significant time observing their mother’s face and activities. Beyond specific skills, nursing interactions teach offspring about social dynamics, appropriate responses to environmental stimuli, and emotional regulation. Young monkeys who experience disrupted nursing relationships often develop abnormal social behaviors and stress responses. The nursing period thus represents a crucial developmental window during which offspring learn not just what to eat, but how to behave within their social and ecological context. This educational component of nursing behavior means that premature weaning can have consequences far beyond nutrition, potentially compromising an individual’s acquisition of critical species-typical and group-specific knowledge.

Nursing behaviors across the animal kingdom represent one of nature’s most profound and versatile adaptations for ensuring offspring survival and development. From the biochemical marvels of mammalian milk production to the specialized feeding adaptations in birds, insects, and even some fish and amphibians, we see repeated evolutionary innovations aimed at delivering optimal nutrition directly from parent to offspring. These behaviors transcend mere feeding, creating contexts for protection, immune development, social bonding, and the transmission of essential knowledge. The remarkable diversity of nursing strategies—from monotremes’ nipple-less milk secretion to marsupials’ synchronized dual-milk production to insects’ trophallaxis—demonstrates how selective pressures have repeatedly shaped parental care systems across disparate evolutionary lineages. Understanding these varied nursing behaviors provides profound insights into not only animal biology but also the fundamental evolutionary processes that have shaped parental care across millions of years of natural selection.

- America’s Most Endangered Mammals And How to Help - August 9, 2025

- The Coldest Town in America—And How People Survive There - August 9, 2025

- How Some Birds “Steal” Parenting Duties From Others - August 9, 2025