Wild camels are extraordinary creatures that have evolved remarkable adaptations to survive in some of the planet’s most extreme environments. From the scorching Gobi to the vast Arabian deserts, these resilient mammals thrive where few other large animals can even subsist. Their legendary ability to endure blistering heat, freezing nights, minimal water, and scarce vegetation has earned them the nickname “ships of the desert.” But how exactly do these magnificent creatures manage to not just survive but flourish in conditions that would be lethal to most other mammals? The answer lies in millions of years of evolutionary adaptations that have transformed camels into supreme desert specialists with biological features uniquely suited to harsh arid environments.

The Two Wild Camel Species

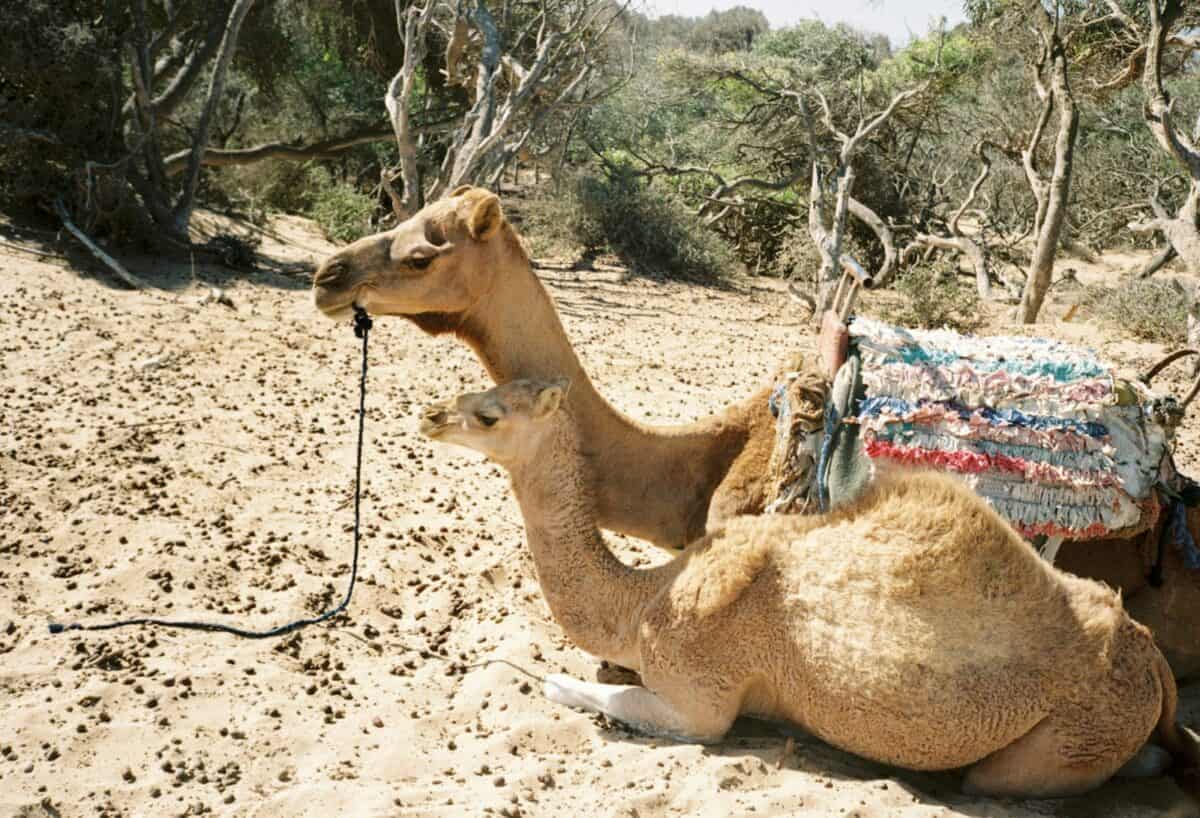

While many people are familiar with domesticated camels, true wild camels are exceedingly rare today. Only two wild camel species exist: the critically endangered wild Bactrian camel (Camelus ferus) and the dromedary camel (Camelus dromedarius), which no longer exists in a truly wild state. The wild Bactrian camel, distinguishable by its two humps, survives in remote pockets of the Gobi Desert spanning Mongolia and China. With fewer than 950 individuals remaining in the wild, they represent one of the most endangered large mammals on Earth. Unlike their domesticated cousins, wild Bactrians have adapted to even harsher conditions, including the ability to drink saltwater when necessary. Today’s feral dromedaries (single-humped camels) found in Australia’s deserts descended from domesticated animals introduced in the 19th century, rather than being truly wild specimens.

The Famous Hump: Fat Storage Brilliance

Perhaps the most iconic feature of camels, their humps represent an ingenious evolutionary adaptation for desert survival. Contrary to popular misconception, camel humps don’t store water—they concentrate fat. This specialized adipose tissue can weigh up to 80 pounds (36 kg) when fully stocked and serves as both a food reserve and a cooling mechanism. By concentrating fat in their humps rather than distributing it throughout their bodies, camels minimize heat insulation across their skin, helping them stay cooler. When food is scarce, camels metabolize this fat reserve, which not only provides energy but also yields water as a byproduct of metabolism. A well-nourished camel can survive up to two weeks without food by relying on its hump reserves. As these reserves are consumed, the hump noticeably shrinks and may even flop to one side until replenished through feeding.

Unparalleled Water Conservation

Wild camels possess the most efficient water conservation systems of any large mammal. Their legendary ability to go without drinking for extended periods—up to two weeks in winter and about a week in summer—stems from multiple physiological adaptations. Unlike most mammals, camels don’t need to sweat to maintain a safe body temperature until the ambient temperature exceeds 108°F (42°C). Their body temperature fluctuates widely, allowing them to withstand heating up during the day without immediate cooling mechanisms. This temperature range can safely vary between 93°F and 105°F (34°C-41°C), which would cause heatstroke in most mammals. Additionally, camel kidneys and intestines are extraordinarily efficient at water reabsorption. Their urine can become as thick as syrup, and their feces are so dry they can be used as fuel for fires almost immediately after excretion. These adaptations allow camels to conserve water so effectively that they can lose up to 25-30% of their body weight in water and still survive—levels that would be fatal for most other mammals.

Remarkable Blood Adaptations

Camel blood contains several unique adaptations that enable desert survival. Their oval-shaped red blood cells (unlike the circular cells found in most mammals) can swell up to 240% of their normal size when hydrated, allowing camels to rapidly absorb and retain large quantities of water when it becomes available. These specialized cells also flow more easily through blood vessels even when dehydration has made the blood significantly thicker. Additionally, camel blood maintains its fluid properties even when water is scarce, preventing the circulatory problems that would kill other animals during severe dehydration. Wild Bactrian camels have demonstrated another extraordinary ability: they can drink brackish or salty water that would cause kidney failure in other mammals. Their specialized kidneys can process highly saline water, an adaptation crucial for survival in parts of the Gobi Desert where freshwater sources are extremely rare and often briny.

Desert-Optimized Respiratory System

Wild camels possess respiratory adaptations specifically evolved for hot, dusty environments. Their nostrils can close completely to block blowing sand during desert storms, a critical protection against the abrasive particles that could damage delicate respiratory tissues. When open, these specialized nostrils trap moisture from exhaled breath, recycling it back into their bodies rather than losing it to the dry desert air. This moisture recovery system significantly reduces water loss during respiration. The camel’s respiratory tract contains additional membranous structures that amplify this water recapture process. Studies have shown that camels lose approximately 50% less moisture through respiration than other mammals of comparable size. This adaptation is particularly valuable during the hottest parts of the day when breathing rates naturally increase. Their complex nasal passages also precool the air before it reaches their lungs, reducing additional water loss that would typically occur during the cooling process.

Extreme Temperature Tolerance

Desert environments experience dramatic temperature fluctuations, often ranging from scorching days exceeding 120°F (49°C) to near-freezing nights. Wild camels have evolved to withstand these extremes without the shelter or thermoregulation tools available to humans. Their thick coat, which appears counterintuitive for a desert animal, actually provides crucial insulation against both heat and cold. This dense fur reflects sunlight during the day, reducing heat absorption, while providing essential warmth during cold desert nights. Wild Bactrian camels grow an especially thick winter coat that they shed when temperatures rise. Additionally, camels possess a specialized tissue layer that separates their body core from their skin surface, allowing their outer body temperature to fluctuate with ambient conditions while maintaining stable internal organs. This adaptation enables them to reduce the temperature gradient between their bodies and the environment, minimizing heat transfer and conserving energy that would otherwise be spent on thermoregulation.

Specialized Digestion for Desert Vegetation

Wild camels have evolved digestive systems capable of extracting maximum nutrition from desert vegetation that other herbivores would find unpalatable or indigestible. Their tough, leathery mouths can handle thorny plants, salt-laden vegetation, and dry, woody desert shrubs that constitute the majority of available food in arid regions. Unlike many other herbivores, camels are not obligate grazers—they are browsers, feeding primarily on shrubs and trees rather than grasses. Their three-chambered stomach (simpler than the four-chambered stomach of cows and other ruminants) contains specialized bacteria that can break down desert plants’ high-cellulose content and neutralize toxic compounds found in many desert flora. This digestive efficiency extends to their ability to extract more calories from less food, enabling survival when vegetation is sparse. Wild Bactrian camels have been observed consuming normally toxic plants like Ephedra and Cynomorium, demonstrating their remarkable digestive resilience and dietary adaptability when faced with limited food options.

Extraordinary Rehydration Abilities

When water finally becomes available, wild camels can rehydrate at an astonishing rate. A severely dehydrated camel can drink up to 30 gallons (114 liters) of water in just 13 minutes—a volume that would cause fatal water intoxication in most other mammals. This rapid rehydration is possible because of their specialized circulatory system, which can accommodate massive fluid influxes without diluting blood electrolytes to dangerous levels. Unlike most mammals, camels don’t experience hemolysis (rupturing of red blood cells) when rehydrating quickly. Their bodies initially store the consumed water in specialized compartments before gradually introducing it into their bloodstream at a manageable rate. This adaptation allows camels to drink rarely but efficiently, taking full advantage of occasional water sources like flash floods or seasonal oases. The ability to rapidly restore their water balance without health consequences represents one of the most remarkable physiological adaptations to desert life in the animal kingdom.

Physical Adaptations for Sandy Terrain

Wild camels navigate loose sand and rocky desert terrain with specialized anatomical features that prevent sinking and provide exceptional stability. Their famous broad, flat feet expand when bearing weight, creating natural “snowshoes” that distribute their substantial body weight (often exceeding 1,500 pounds in males) across a larger surface area. Each foot has two toes connected by a flexible, webbed pad that prevents them from sinking into soft sand. These specialized feet contain thick calluses that insulate against scorching sand that can reach temperatures of 160°F (70°C). Additionally, camels have evolved to move both legs on one side simultaneously—creating their distinctive swaying gait—which increases stability and conserves energy when walking on unstable surfaces. Their long legs keep their bodies elevated farther from the hot ground, reducing heat absorption from below. Wild Bactrian camels even develop tougher, more insulated footpads during winter months when crossing frozen terrain in the Gobi Desert, demonstrating their adaptive physical plasticity across seasons.

Behavioral Desert Survival Strategies

Wild camels employ sophisticated behavioral adaptations that complement their physiological traits. They are crepuscular, being most active during dawn and dusk while resting during the hottest parts of the day, often orienting themselves to minimize sun exposure. During sandstorms, they crouch low with their backs to the wind, close their nostrils and eyes, and create a protective microclimate around their faces. Wild Bactrian camels have been observed digging depressions in the sand to reach cooler substrates or expose hidden water sources that may be several feet below the surface. They possess exceptional spatial memory, remembering the locations of seasonal water sources and migration routes across vast desert expanses. Wild camels also exhibit social behaviors that enhance survival, including forming small, flexible groups that can rapidly mobilize when water or vegetation is discovered. During breeding season, dominant males establish temporary territories around critical resources, ensuring their priority access while tolerating females and young, a strategy that balances reproductive competition with the pragmatic need for group survival in harsh conditions.

Desert Navigation and Sensory Adaptations

Navigating featureless desert expanses requires exceptional sensory capabilities, and wild camels possess several unique adaptations in this realm. Their elevated eye position provides an expanded horizon view, allowing them to detect distant water sources, vegetation patches, or approaching storms. Specialized nostrils can detect moisture in the air from remarkable distances—some research suggests they can smell water from as far as 50 miles (80 km) away under favorable conditions. Their hearing is finely tuned to low-frequency sounds that travel farther in desert environments, alerting them to distant rainfall or the presence of other camels. Perhaps most impressive is their ability to detect subtle changes in barometric pressure and wind patterns that precede weather shifts, enabling them to anticipate approaching storms or potential rainfall areas. Wild camels are also guided by celestial navigation, orienting themselves using star patterns during night travels—a behavior documented in wild Bactrian populations that undertake seasonal migrations across the Gobi. These combined sensory capabilities allow them to locate critical resources across vast desert territories and anticipate environmental changes before they become apparent to other species.

Conservation Challenges for Wild Camels

Despite their remarkable adaptations, wild camel populations face severe conservation challenges. The wild Bactrian camel is critically endangered, with fewer than 950 individuals surviving in remote regions of the Gobi Desert. Their decline stems from multiple threats, including competition with domestic livestock for scarce water and vegetation, illegal hunting, habitat fragmentation due to mining operations, and hybridization with domestic Bactrian camels. Climate change presents an additional threat, as even these desert specialists face limits to their adaptive capabilities. Rising temperatures and increasingly unpredictable rainfall patterns disrupt the delicate balance of desert ecosystems. Conservation efforts include strict protection of the Great Gobi Strictly Protected Area in Mongolia and the Lop Nur Wild Camel National Nature Reserve in China. The Wild Camel Protection Foundation works to establish breeding programs and protected corridors between isolated populations. However, conservation is complicated by the remote, harsh terrain these animals inhabit and limited resources allocated to their protection. Without increased conservation efforts, we risk losing one of evolution’s most remarkable success stories—mammals that conquered Earth’s most challenging environments through millions of years of specialized adaptation.

Wild camels represent one of nature’s most impressive evolutionary achievements, embodying the pinnacle of adaptation to extreme environments. Their suite of physiological, anatomical, and behavioral specializations allows them to thrive in conditions that would quickly prove fatal to most other large mammals. From their efficient water conservation systems and temperature regulation mechanisms to their specialized feet and digestive capabilities, every aspect of camel biology reflects millions of years of evolutionary refinement for desert survival. These remarkable adaptations demonstrate the incredible plasticity of life and nature’s capacity to find solutions to even the most challenging environmental conditions. As we face growing environmental challenges globally, the study of wild camels offers valuable insights into biological resilience and adaptation that may inform our understanding of how species respond to extreme conditions—lessons that grow increasingly relevant in our rapidly changing world.

- 10 Unique Animal Species That Can Only Be Found in the United States - August 15, 2025

- 10 Amazing Animals You Can Only Find in the United States - August 15, 2025

- 10 Times Tornadoes Flattened Entire Towns in the Midwest - August 15, 2025