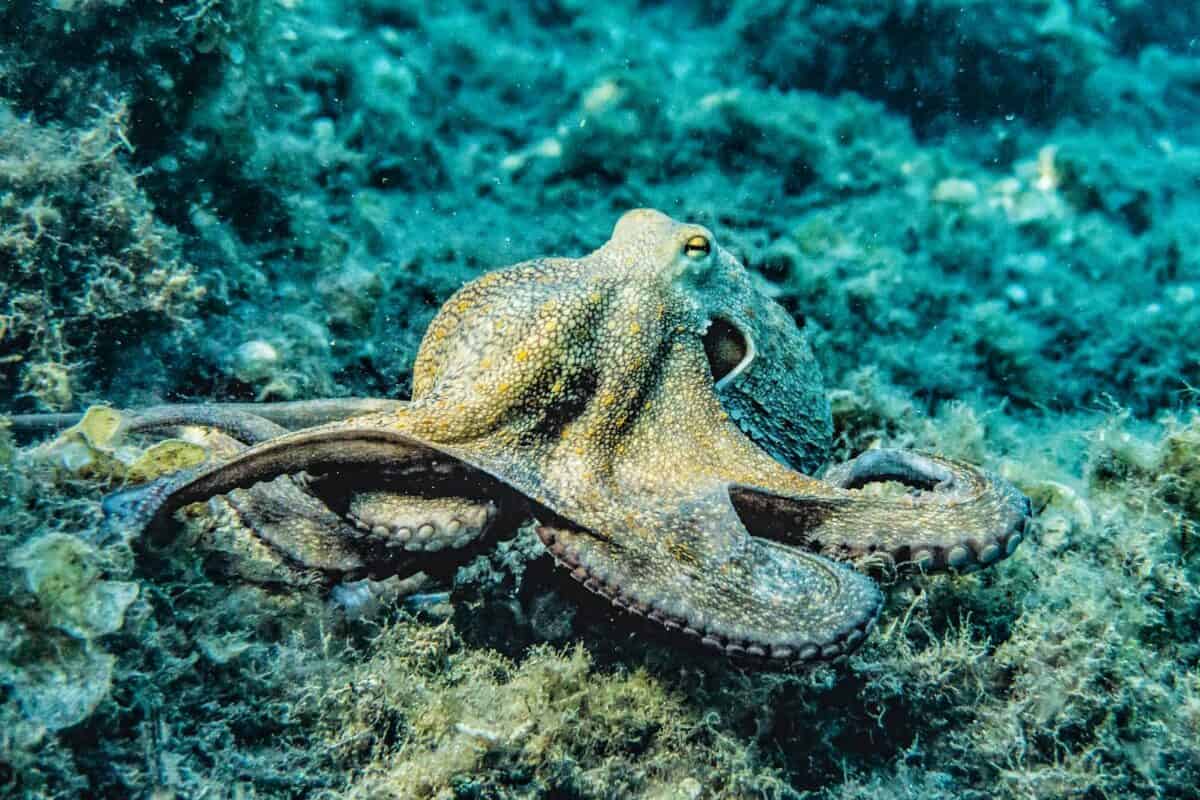

In the mysterious depths of the ocean, octopuses reveal themselves as nature’s ultimate home decorators. These remarkable cephalopods don’t simply find shelter—they transform their dwellings into personalized spaces adorned with collected treasures from the seafloor. From colorful shells and discarded bottles to coral fragments and even human debris, certain octopus species curate their surroundings with an apparent aesthetic sensibility that has fascinated marine biologists for decades. This behavior, initially overlooked as random, has emerged as a complex aspect of octopus intelligence and adaptation strategies. The octopus’s home decoration habits offer a fascinating glimpse into the sophisticated minds of these eight-armed architects of the sea.

The Decorator Crab Connection – Understanding Octopus Home Adornment

Octopus home decoration behavior shares fascinating parallels with decorator crabs, though it evolved independently through convergent evolution. While decorator crabs primarily attach items to their shells for camouflage, octopuses employ more varied motivations for their collecting habits. The veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus), commonly known as the coconut octopus, demonstrates perhaps the most sophisticated decoration behavior, selecting coconut shell halves and large bivalve shells to create mobile protective shelters. This behavior represents a unique evolutionary adaptation that combines tool use with home modification. Scientists believe this parallel development of decoration behaviors between such different marine creatures highlights how protective and territorial behaviors can manifest similarly across unrelated species when they face similar environmental pressures and predation risks.

The Amphioctopus marginatus – The Coconut Octopus’s Strategic Decorating

The veined octopus or coconut octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) has earned international scientific recognition for its sophisticated home decoration behavior. Native to the tropical waters of the Western Pacific, this medium-sized octopus selects coconut shell halves and large clam shells, which it cleans meticulously before arranging into protective shelters. In a behavior that astounded researchers, these octopuses have been documented carrying collected shells across the ocean floor by “stilt-walking” – moving on two arms while holding their shells with the remaining limbs. This was one of the first documented cases of tool use in invertebrates. The coconut octopus doesn’t merely decorate its home; it essentially builds portable armor, which it can assemble quickly when threatened. This strategic decoration serves both as protection and as a mobile home, allowing the octopus to enjoy the benefits of shelter while maintaining the freedom to travel across its territory.

Octopus tetricus – The Gloomy Octopus’s Collection Habits

The gloomy octopus (Octopus tetricus), found in the waters around Australia and New Zealand, has developed fascinating decoration behaviors that contribute to what scientists have termed “octopus gardens.” These social aggregations, discovered in Jervis Bay, Australia, feature multiple octopuses living in close proximity—an unusual arrangement for typically solitary creatures. Research published in the journal Marine and Freshwater Behaviour and Physiology documented how these octopuses collect scallop shells and other marine debris to fortify the entrances to their dens. The octopuses actively maintain these decorated areas, pushing away unwanted objects and rearranging their collections. Interestingly, the aggregation of these decorated dens creates a modified habitat that attracts other marine species, effectively establishing a small ecosystem centered around the octopuses’ decorative preferences. This behavior demonstrates how octopus decoration habits can extend beyond individual benefits to influence broader ecological patterns.

The Science Behind Collecting Behavior

The collecting and decorating behaviors observed in octopuses stem from a combination of innate instincts and advanced cognitive abilities. Neurobiological studies have revealed that octopuses possess complex brain structures with specialized areas for learning, memory, and problem-solving. The vertical lobe, analogous in some ways to the hippocampus in mammals, allows octopuses to remember the location of valuable decorative items and to learn from experience which objects provide the best protection or camouflage. Research published in the Journal of Comparative Psychology indicates that these behaviors involve both tactile exploration and visual assessment, with octopuses manipulating potential decorative items extensively before deciding whether to keep them. The collecting behavior appears to be partially instinctive but refined through experience, with captive studies showing that individual octopuses develop preferences for certain colors, textures, and shapes based on their previous interactions with objects. This sophisticated neural underpinning allows octopuses to make complex decisions about which items will best serve their protective, territorial, or possibly even aesthetic needs.

Beyond Protection – Possible Aesthetic Motivations

While the protective function of octopus decorating behavior is well-established, some marine biologists speculate about possible aesthetic motivations behind their collecting habits. Observations of captive octopuses have documented individuals repeatedly rearranging colorful objects in their tanks with no apparent survival benefit. In one notable study at the Seattle Aquarium, a giant Pacific octopus repeatedly positioned a red plastic block in the center of its den, returning it to this specific location whenever it was moved by researchers. Cephalopod cognition experts, like Dr. Jennifer Mather of the University of Lethbridge, suggest that such behaviors may indicate rudimentary aesthetic preferences or environmental enrichment seeking. While anthropomorphizing animal behavior carries scientific risks, the sophisticated cognitive capabilities of octopuses—including their excellent color vision despite being colorblind themselves—provides some basis for considering that their decoration behaviors might extend beyond pure utility. This remains a fascinating frontier in cephalopod research, challenging our understanding of animal cognition and the possible emergence of proto-aesthetic behaviors in highly intelligent invertebrates.

Cultural Significance of Octopus Home Decoration

The home decoration behavior of octopuses has captured human imagination, influencing cultural representations and scientific understanding of animal intelligence. This behavior featured prominently in award-winning documentaries like “My Octopus Teacher” and “The Octopus in My House,” helping to transform public perception of cephalopods from alien creatures to intelligent beings with complex behaviors. The coconut octopus’s shell-carrying behavior, in particular, has become an iconic example used in educational materials to illustrate animal tool use beyond primates and birds. In indigenous cultures of the Western Pacific, where coconut octopuses are common, local knowledge of these behaviors predated scientific documentation by centuries, with folklore often depicting octopuses as clever collectors and builders. The cultural impact of these discoveries has contributed to growing ethical concerns about cephalopod welfare in research and aquaculture, with several countries now including octopuses in animal welfare legislation due to recognition of their cognitive complexity. Their decoration behaviors serve as powerful evidence of invertebrate intelligence that challenges traditional hierarchical views of animal cognition.

Unusual Decorative Items – From Sea Glass to Human Artifacts

Octopuses display remarkable creativity in their choice of decorative items, often incorporating human-made objects alongside natural materials. Marine biologists have documented octopuses collecting colorful sea glass, bottle caps, plastic toys, and even watch batteries to adorn their homes. In one remarkable case observed off the coast of Vancouver Island, researchers found a giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) that had decorated its den entrance with an arrangement of metal fishing lures, their colors still vibrant despite long exposure to seawater. The octopus appeared to have positioned these reflective items to catch the limited light that penetrated to its depth. In aquariums, octopuses have been observed arranging LEGO blocks, marbles, and other colorful toys into patterns around their dens. This adaptability in using anthropogenic materials demonstrates the opportunistic nature of octopus intelligence and raises interesting questions about how human ocean pollution might be affecting their natural behaviors. Some researchers speculate that the increased presence of colorful plastic in marine environments may be inadvertently providing octopuses with more decorative options, potentially altering their traditional collecting habits in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Territorial Marking Through Decoration

Beyond their protective function, octopus decorations often serve as sophisticated territorial markers. Research conducted at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, has shown that certain octopus species arrange objects in patterns that appear to delineate the boundaries of their territories. The common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) has been observed creating distinctive “walls” of rocks and shells that extend outward from their den entrances, effectively creating a visual perimeter that signals ownership to other octopuses. These territorial decorations can contain chemical signals as well, as octopuses secrete compounds through their skin that adhere to the objects they handle frequently. A 2018 study published in the Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology demonstrated that octopuses can detect these chemical signatures on decorated items and will avoid areas marked by the decorations of larger conspecifics. This chemical-visual dual marking system represents an advanced territorial behavior that helps avoid direct confrontations in a species that generally prefers to avoid physical conflict. Interestingly, when octopuses abandon a den, they typically leave their decorations behind, potentially creating a historical record of occupation that can inform other octopuses about site quality and previous inhabitants.

Octopus Decoration as a Form of Tool Use

The home decoration behaviors of octopuses qualify as sophisticated tool use according to contemporary definitions in comparative cognition. When octopuses like the veined octopus (Amphioctopus marginatus) select, transport, and arrange coconut shells as portable shelters, they demonstrate the key elements of tool use: object manipulation for a specific purpose, modification of the environment, and the extension of physical capabilities. In a groundbreaking 2009 study published in Current Biology, researchers documented coconut octopuses collecting shell halves, cleaning them of sediment, and carrying them for future use—behaviors that require planning and foresight. This discovery challenged long-held assumptions that tool use was limited to vertebrates with larger brains. Unlike instinctive nest-building behaviors in birds or insects, octopus decoration involves flexible decision-making, with individuals assessing the quality of potential items and rejecting those that don’t meet their standards. The octopus must solve complex physical problems, such as how to transport awkward objects across the seafloor and how to arrange multiple items for maximum effectiveness. This cognitive flexibility places octopus decoration at the sophisticated end of the tool-use spectrum, comparable in some ways to the tool behaviors seen in corvids (crows and ravens) and some primates.

How Environmental Factors Influence Decoration Choices

The decoration behaviors of octopuses are heavily influenced by their local environment, creating regional variations in material preferences and arrangement styles. In sandy habitats with few natural shelters, octopuses tend to collect more substantial protective items like large shells and coconut halves. Conversely, in rocky environments with abundant natural crevices, they often focus on collecting smaller items for camouflage or den entrance fortification. Water current strength also shapes decoration strategies, with octopuses in high-current areas selecting heavier, more stable objects that won’t be displaced by water movement. Research conducted in the Philippines demonstrated that veined octopuses living near coastal villages collected a higher percentage of human-made objects than their counterparts in more remote locations, showing adaptive flexibility in material selection. Seasonal variations have also been documented, with some octopus species collecting more decorative items during breeding seasons, possibly to make their dens more attractive to potential mates or more defensible against competitors. Climate change may be altering these behaviors as well—a long-term study in the Mediterranean found that as water temperatures increased, common octopuses (Octopus vulgaris) collected more reflective objects, potentially seeking to create cooler microenvironments within their dens. These environmental influences highlight the octopus’s remarkable ability to adapt its decoration strategies to local conditions and changing circumstances.

Observing Decoration Behavior in Captivity

Aquariums and research facilities have provided valuable insights into octopus decoration behaviors through controlled observation. When provided with diverse objects, captive octopuses often demonstrate clear preferences, with studies at the Monterey Bay Aquarium showing that giant Pacific octopuses (Enteroctopus dofleini) typically select objects with rough textures and bright colors when given equal access to various items. Researchers have documented that captive octopuses will rearrange their tanks overnight, sometimes creating elaborate constructions that weren’t present the previous evening. Enrichment protocols in modern aquariums now routinely include providing octopuses with novel objects specifically for decoration and manipulation. Time-lapse photography has revealed that octopuses may spend several hours meticulously arranging their collected items, using different arms for different aspects of the decoration process. One fascinating observation from laboratory settings is that octopuses appear to “test” the properties of potential decorative items, manipulating them extensively before deciding whether to incorporate them into their dens. This behavior suggests a sophisticated assessment process based on multiple sensory inputs. However, researchers caution that captive observations must be interpreted carefully, as the artificial environment and limited material choices may influence octopus behavior in ways that differ from wild populations. Nevertheless, these controlled studies have been instrumental in establishing that decoration behavior involves active choice rather than random accumulation of objects.

The home decoration behaviors of octopuses reveal the remarkable cognitive sophistication of these invertebrates, challenging our understanding of animal intelligence and tool use. Through their selective gathering, transportation, and arrangement of objects, octopuses demonstrate problem-solving abilities, environmental adaptation, and possibly even proto-aesthetic sensibilities that blur traditional boundaries between vertebrate and invertebrate cognition. These behaviors serve multiple adaptive functions—from physical protection and territorial marking to potential mate attraction—highlighting how octopuses have evolved complex behavioral strategies despite their relatively short lifespan of 1-3 years. As ocean environments change due to human impact, the decoration behaviors of octopuses may serve as sensitive indicators of marine ecosystem health, with shifts in material selection potentially reflecting broader environmental alterations. Future research using non-invasive observation techniques promises to further unravel the cognitive mechanisms behind these fascinating behaviors, potentially leading to new insights about the evolution of intelligence across distantly related animal groups.

- How Some Octopuses Decorate Their Homes With Found Objects - August 12, 2025

- The Smartest Small Dog Breeds Ranked - August 12, 2025

- The Colourful Beauty of the Resplendent Quetzal - August 12, 2025