The animal kingdom offers a fascinating glimpse into the diverse ways mothers care for their young, often displaying remarkable behaviors that parallel human maternal instincts while also demonstrating unique adaptations shaped by evolution. From mammals that nurse their young for years to insects that sacrifice their lives for their offspring, motherhood in nature reveals both touching similarities to human parenting and extraordinary differences. This exploration of animal motherhood not only provides scientific insights into the biological foundations of maternal care but also offers philosophical reflections on the universal aspects of nurturing the next generation. Through understanding how various species approach motherhood, we can gain deeper appreciation for the evolutionary roots of our own parenting instincts and perhaps even draw inspiration from the resilience, creativity, and dedication of animal mothers facing the challenges of survival and reproduction.

The Evolutionary Purpose of Maternal Care

Maternal care evolved across species as a crucial strategy to ensure offspring survival and, consequently, the continuation of genetic lineages. This fundamental biological imperative takes remarkably diverse forms across the animal kingdom. In evolutionary terms, maternal investment represents a delicate balance between current reproduction and future reproductive potential. Mothers that devote excessive resources to current offspring might diminish their ability to reproduce later, while insufficient investment could result in offspring failing to thrive.

The degree of maternal care typically correlates with reproductive strategy. K-selected species, which produce fewer offspring with greater individual investment, generally exhibit more extensive maternal care than r-selected species, which produce numerous offspring with minimal individual investment. This difference explains why an elephant might devote years to raising a single calf while a sea turtle lays hundreds of eggs and departs immediately. Fascinatingly, maternal care has evolved independently multiple times across different animal lineages, suggesting its powerful adaptive value across diverse ecological niches.

Mammalian Devotion: Nursing and Nurturing

Mammals stand apart in the animal kingdom for their distinctive approach to motherhood, centered around lactation—the production of milk to nourish their young. This nutritional strategy provides offspring with perfectly tailored sustenance while creating powerful bonds between mother and young. The composition of mammalian milk varies dramatically between species, reflecting evolutionary adaptations to different environmental challenges and developmental needs. For instance, marine mammals like seals produce milk with up to 50% fat content, enabling rapid growth in cold environments, while primate milk contains relatively less fat but more complex carbohydrates supporting brain development.

Beyond nursing, mammalian mothers engage in extensive nurturing behaviors. Female lions not only nurse their cubs but also teach hunting skills and defend them against threats, including male lions that might kill them. Elephant matriarchs lead multi-generational family groups, with female relatives helping care for calves in a system called allomothering. This cooperative care ensures that young elephants learn complex social behaviors and survival skills during their extended developmental period. These examples illustrate how mammalian motherhood extends far beyond nutrition to encompass protection, education, and social integration—paralleling many aspects of human maternal care.

Marsupial Innovation: The Pouch as Protection

Marsupials like kangaroos, koalas, and opossums have evolved one of nature’s most distinctive maternal care systems through their specialized pouches (marsupium). Unlike placental mammals that nurture developing embryos internally until birth at a relatively advanced stage, marsupials give birth to extremely underdeveloped offspring—sometimes after just a few weeks of gestation. A newborn kangaroo joey, for instance, weighs less than a gram and measures about 2 centimeters, resembling an embryonic stage in placental mammals.

The mother’s pouch becomes a remarkable external womb where this development continues. Newborn joeys instinctively crawl from the birth canal into the mother’s pouch, attach to a teat, and remain there for months while continuing to develop. The kangaroo mother can simultaneously produce different milk compositions from different teats—one formulated for a newborn in the pouch and another for an older joey that has begun to explore outside the pouch but still returns to nurse. This extraordinary adaptation allows marsupial mothers to continue reproductive cycles while caring for existing offspring, a strategy particularly valuable in Australia’s unpredictable climate, where resources may be inconsistently available.

Avian Architects: Nest Construction and Incubation

Bird mothers demonstrate remarkable engineering and dedication in creating safe environments for their developing offspring. Nest construction represents a sophisticated form of parental investment, with designs ranging from the simple scrapes of ground-nesting birds to the elaborate woven structures of weaverbirds. The female bald eagle constructs massive nests weighing up to a ton that may be used for generations. Female hornbills take nest protection to extremes—after entering a tree cavity to lay eggs, they seal themselves inside with mud, feces, and food remains, leaving only a narrow slit through which the male passes food during the weeks of incubation and early chick development.

Incubation behavior demonstrates equally impressive maternal devotion. Many bird species develop a brood patch—an area of featherless, blood-vessel-rich skin that efficiently transfers body heat to eggs. Emperor penguin mothers lay a single egg and then transfer it to the father’s feet for incubation while they journey to sea to feed. When they return months later, they recognize their mates and chicks through distinctive calls. Some bird species, like the American flamingo, produce crop milk—a nutritious secretion from the digestive tract—demonstrating a convergent evolution of “nursing” behavior similar to mammals. These varied strategies highlight how avian mothers have evolved specialized adaptations to protect vulnerable eggs and chicks from predation and environmental challenges.

Reptilian Strategies: From Abandonment to Vigilance

Reptilian motherhood presents a fascinating spectrum of parental investment strategies, challenging common assumptions about these animals’ maternal instincts. Many reptile species are indeed characterized by minimal parental care—sea turtles famously travel thousands of miles to ancestral nesting beaches, dig carefully constructed nests, lay their eggs, and then return to the ocean, never to see their hatchlings. This strategy evolved in response to aquatic lifestyles incompatible with egg incubation and reflects a trade-off favoring quantity of offspring over individual attention.

At the other end of the spectrum are crocodilians, whose maternal behaviors rival those of many mammals. Female American alligators construct large vegetation nests that generate heat through decomposition, carefully maintain optimal nest temperature by adding or removing material, and respond aggressively to any threats near the nest. When hatchlings begin making distinctive vocalizations from within unhatched eggs, the mother gently uncovers them and carries the newly hatched young to water in her mouth. She may continue protecting her young for up to two years. Python mothers coil around their eggs for months, “shivering” to generate body heat—a behavior requiring significant energy expenditure and demonstrating that even “cold-blooded” reptiles can evolve complex maternal behaviors when selection pressures favor such investment.

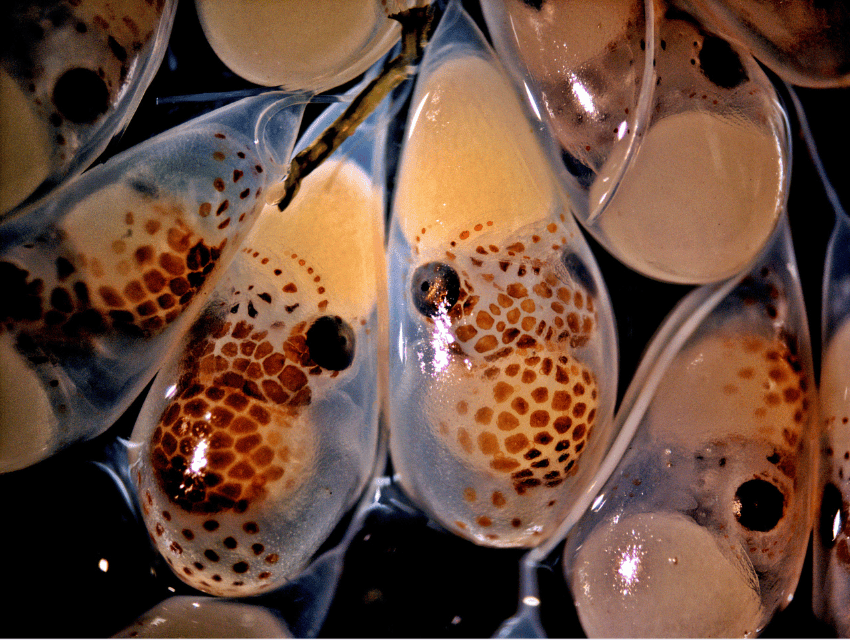

Amphibian Adaptations: Creative Solutions for Vulnerable Offspring

Amphibians face unique reproductive challenges due to their dual lifestyle between aquatic and terrestrial environments, driving the evolution of some of nature’s most creative maternal strategies. The African bullfrog mother creates escape routes from drying pools by digging channels with her hind legs, allowing tadpoles to reach larger water bodies. Strawberry poison dart frogs carry individual tadpoles on their backs to deposit each one in a separate water-filled bromeliad leaf, returning to feed each tadpole with unfertilized eggs until they metamorphose.

Perhaps most remarkable are the gastric-brooding frogs of Australia (now sadly extinct), whose mothers would swallow their fertilized eggs. The mother’s stomach would cease producing acid, becoming a living nursery until she eventually regurgitated fully formed froglets. Similarly, the Surinam toad embeds eggs into specialized pockets on her back, where they develop until emerging as miniature toadlets. The Darwin’s frog father (rather than mother) guards eggs until they reach a wriggling stage, then swallows them into his vocal sac, where they complete development before being “coughed up” as fully formed froglets. These extraordinary adaptations demonstrate how the challenges of raising vulnerable offspring in hostile environments have driven the evolution of highly specialized maternal (and sometimes paternal) care strategies.

Fish Mothers: Surprising Underwater Parenting

Fish exhibit a remarkable diversity of maternal behaviors, challenging the stereotype of them abandoning their offspring. While many species indeed release thousands of eggs into the water column with no further investment, others demonstrate sophisticated maternal care. Female mouthbrooding cichlids from Lake Malawi and Lake Tanganyika provide perhaps the most striking example, incubating fertilized eggs in their mouths for weeks. During this period, mothers cannot eat and lose significant body mass while constantly circulating oxygen-rich water around the developing embryos. When danger threatens, developed fry can dart back into their mother’s mouth for protection.

Some fish species take maternal protection to extraordinary levels. The female giant Pacific octopus (technically not a fish but deserving inclusion) guards her eggs for months without eating, eventually dying after her offspring hatch—the ultimate maternal sacrifice. Seahorse reproduction famously features pregnant males rather than females, but this represents a unique evolutionary division of reproductive labor rather than an absence of maternal investment. Female seahorses produce energy-rich eggs and transfer them to the male’s specialized brood pouch. The female’s biological investment in egg production represents substantial maternal care, even though gestation occurs in the male. These diverse strategies demonstrate how selective pressures in aquatic environments have shaped a wide range of maternal adaptations across fish species.

Insect Extremes: Ultimate Sacrifice and Mass Production

Insect motherhood spans from extreme sacrifice to minimal investment, reflecting the tremendous diversity of this group that represents over 80% of animal species. Female worker ants, bees, and wasps represent a radical evolutionary development—they are effectively non-reproductive mothers, caring for their siblings rather than their own offspring in a sophisticated division of reproductive labor. The sole reproducing female—the queen—specializes in egg production while her daughters perform maternal duties. This evolutionary strategy has proven remarkably successful, with social insects dominating many ecosystems.

Some insect mothers make the ultimate sacrifice. Female Stegodyphus spiders allow their spiderlings to consume them through a process called matriphagy—the mother liquefies her internal organs as her offspring consume her, providing crucial nutrition for their development. The female Atrax robustus spider seals herself into her egg chamber, where she will die after her spiderlings hatch. Earwig mothers demonstrate surprisingly sophisticated care, cleaning eggs to prevent fungal infections and retrieving any that roll away. Female burying beetles transform small animal carcasses into nurseries by removing fur or feathers, coating the remains with antimicrobial secretions, and regurgitating predigested food for their larvae. These diverse examples highlight how even animals with relatively simple nervous systems can evolve complex maternal behaviors when selection pressures favor such investments.

Cooperative Mothering: It Takes a Village

Across the animal kingdom, cooperative maternal care strategies demonstrate that motherhood need not be a solitary endeavor. African elephants exemplify this approach, with herds structured around related females led by an experienced matriarch. Aunts, sisters, and grandmothers all participate in calf-rearing, protecting youngsters from predators, teaching them to use their trunks, and even producing milk to nurse calves that are not their own. This cooperative approach ensures that elephant calves—which require years of development—benefit from collective wisdom and protection.

Meerkats practice a similar system where older daughters serve as “babysitters” for the dominant female’s pups while she forages. These helpers gain valuable parenting experience that will benefit them when they eventually reproduce. Among lions, related females in a pride synchronize their breeding when possible, creating a communal nursery where cubs receive care and milk from multiple mothers. Perhaps most remarkably, in some bird species like the superb fairy-wren, unrelated females may help raise another pair’s offspring, apparently as a form of “rent payment” for territory access. These cooperative strategies highlight how the challenges of raising offspring have, in many species, driven the evolution of shared maternal responsibility that distributes costs while ensuring young animals receive comprehensive care and training.

The Motherhood-Environment Connection

Animal mothers demonstrate remarkable plasticity in their maternal behaviors in response to environmental conditions, illustrating how motherhood adaptively responds to external factors. Red squirrels can predict future food availability based on conifer cone production and adjust their reproductive timing and investment accordingly. In years preceding abundant cone crops, females produce larger litters earlier in the season, demonstrating a form of predictive maternal programming. Kangaroo mothers simultaneously carry joeys at different developmental stages and can pause the development of an embryo during drought conditions until resources improve—a remarkable adaptation called embryonic diapause.

Climate change and habitat disruption are now challenging these finely tuned maternal adaptations. Polar bear mothers, which typically fast for months while nursing cubs in snow dens, face shorter winters and reduced hunting opportunities on diminishing sea ice, compromising their ability to produce sufficient milk. Turtle mothers that lay eggs on beaches threatened by rising sea levels and increased storm frequency face reproductive failure as nests are flooded. Monarch butterfly mothers must locate increasingly rare milkweed plants on which to lay eggs, as agricultural practices eliminate these essential host plants. These examples highlight how anthropogenic environmental changes are disrupting maternal strategies that evolved over millions of years, forcing animal mothers to attempt adaptations within timeframes much shorter than those in which these behaviors originally evolved.

Human Parallels: What We Share with Animal Mothers

Despite our cultural sophistication, human motherhood shares fundamental biological and behavioral foundations with other animals. The neurohormonal mechanisms triggering maternal behavior are remarkably conserved across mammalian species. Oxytocin—often called the “love hormone”—plays a crucial role in maternal bonding in humans, other primates, rodents, and even sheep. This common biochemical pathway suggests ancient evolutionary roots for the emotional attachment between mothers and their offspring. Similarly, the biochemical composition of human breast milk, with its complex immunological properties and changing formulation to meet infant developmental needs, parallels adaptations seen in other mammals.

On a behavioral level, human mothers instinctively engage in practices observed across many species—protecting children from threats, teaching essential skills, and providing nutrition at personal cost. The intense bond many human mothers describe—being willing to sacrifice anything for their child’s welfare—mirrors behaviors like a mother elephant charging predators despite personal risk or a mother bird feigning injury to draw predators away from her nest. While human motherhood is undoubtedly shaped by culture, technology, and social structures, these parallels with other species remind us that maternal care emerges from deep evolutionary history. Understanding this shared biological heritage can validate the powerful instincts many human mothers experience while highlighting how cultural practices and social support can complement these natural tendencies.

The exploration of motherhood across the animal kingdom reveals both astonishing diversity and profound commonalities in how different species approach the fundamental challenge of raising offspring. From the extreme sacrifice of spider mothers who offer their bodies as their offspring’s first meal to the decades-long commitment of elephant matriarchs who guide multiple generations, maternal care strategies reflect millions of years of evolutionary refinement. These varied approaches—whether focused on quantity of offspring or quality of care—have proven successful in their specific ecological contexts, demonstrating that there is no single “correct” way to mother, but rather a spectrum of solutions to the universal challenge of perpetuating genetic lineages.

For human observers, animal motherhood offers both scientific insights and philosophical reflection. The biochemical foundations of maternal behavior highlight our deep connection to other species, while the tremendous diversity of parenting strategies reminds us that human approaches to motherhood—which vary considerably across cultures and historical periods—exist within a broader natural context. Perhaps most importantly, animal mothers demonstrate remarkable resilience and adaptability, continuing to nurture their young despite environmental challenges, resource limitations, and predatory threats. In this resilience, there may be lessons for human society about the importance of supporting mothers with social structures that recognize the biological and emotional demands of raising the next generation.

As we face unprecedented global challenges affecting all species, the study of animal motherhood underscores the universal value of maternal care to ecological systems and species survival. Conservation efforts that fail to account for the specialized needs of animal mothers and their offspring risk undermining the reproductive success of vulnerable species. By understanding and respecting the maternal adaptations that have evolved across the animal kingdom, we gain not only scientific knowledge but also a deeper appreciation for the powerful biological imperative that drives mothers of all species to nurture, protect, and prepare their young for the challenges ahead.

- How Wild Dolphins Use Medicinal Coral to Heal Wounds - August 17, 2025

- 11 Common Animals With Secret Abilities You Never Knew About - August 17, 2025

- 9 Times Dogs Showed Unbelievable Loyalty to Their Owners - August 17, 2025