In restaurants across the world, lobsters are often boiled alive before being served as a delicacy. This practice has existed for centuries, with lobster meat considered a luxurious treat by many. Yet in recent years, a profound ethical question has emerged: Are lobsters merely seafood, or are they sentient beings capable of experiencing pain and suffering? This debate has grown increasingly heated, pitting culinary traditions against animal welfare concerns, and challenging us to reconsider our relationship with these fascinating creatures. As science advances our understanding of lobster neurobiology and behavior, legislators, chefs, and consumers alike find themselves navigating complex moral territory that blurs the line between gastronomic pleasure and ethical responsibility.

The Cultural History of Lobster Consumption

Lobster hasn’t always held its current status as an expensive delicacy. In colonial America, lobsters were so abundant that they washed ashore in piles two feet high. They were considered a low-status food, fed to prisoners, servants, and livestock. Some servants even had clauses in their contracts limiting how frequently they could be fed lobster. The crustacean was commonly used as fertilizer and fish bait before it gained culinary prominence.

The transformation of lobster into a luxury food began in the mid-19th century with the development of canning and railway transportation, allowing lobster to be shipped inland. By the early 20th century, lobster had become associated with fine dining and social status. This cultural shift highlights how our relationship with lobster as food is not static but has evolved significantly over time, shaped by economic, technological, and social factors rather than inherent qualities of the creature itself.

The Science of Lobster Sentience

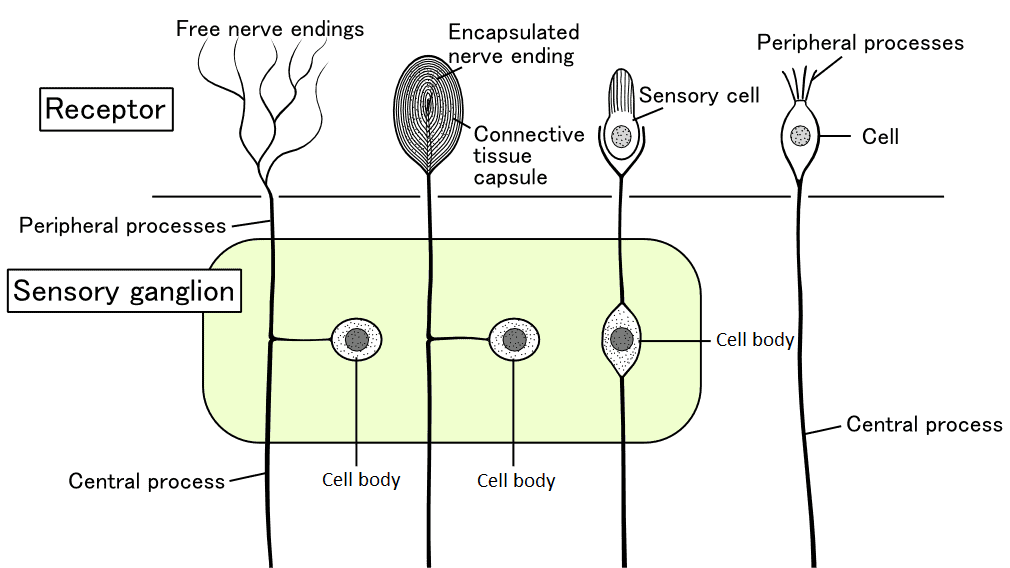

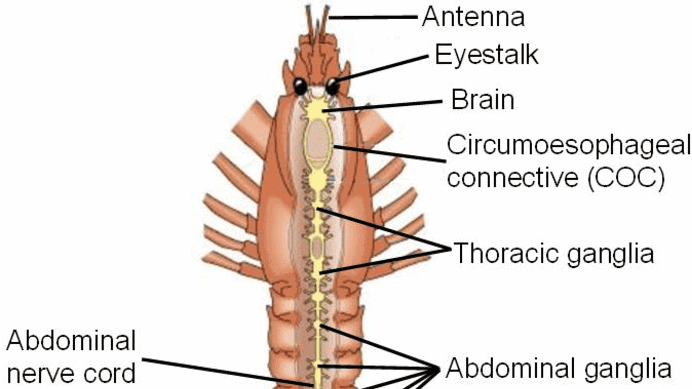

The question of whether lobsters can feel pain hinges on our understanding of their nervous systems. Lobsters possess a decentralized nervous system rather than a centralized brain like mammals. They have ganglia—clusters of nerve cells—distributed throughout their bodies. For decades, this was used as evidence that lobsters couldn’t feel pain in a meaningful way. However, recent scientific studies have challenged this assumption, suggesting that the absence of a centralized brain doesn’t necessarily preclude the experience of pain or discomfort.

Research published in the journal Science in 2022 identified nociceptors—sensory neurons that respond to harmful stimuli—in lobsters. When exposed to harmful conditions, lobsters exhibit avoidance behaviors consistent with pain response, such as rubbing injured areas and avoiding locations where they previously experienced negative stimuli. They also produce stress hormones similar to those released by mammals under duress. While lobsters may not experience pain in the same way humans do, growing scientific consensus suggests they possess some form of sentience and capacity for suffering that merits ethical consideration.

Legal Recognition of Lobster Sentience

Several jurisdictions have begun formally recognizing lobsters as sentient beings deserving of protection. In 2018, Switzerland banned the practice of boiling lobsters alive, requiring that they be stunned or killed instantly before cooking. The Swiss government stated this was based on scientific evidence that lobsters can feel pain. The United Kingdom’s Animal Welfare (Sentience) Act of 2022 officially recognized all decapod crustaceans, including lobsters, as sentient beings, acknowledging their capacity to experience feelings including pain.

New Zealand and Norway have also implemented legislation protecting crustacean welfare, while the European Union has identified lobsters as animals that should be considered for welfare protection in future legislation. These legal developments represent a significant shift in how societies view these creatures, moving them from the category of “seafood” toward recognition as beings with inherent welfare interests. The legal trend clearly points toward increased protection for lobsters, even as they remain a commercially important food source.

Traditional Cooking Methods and Welfare Concerns

The traditional method of cooking lobsters—dropping them alive into boiling water—has become the focal point of the sentience debate. This practice originated partly for food safety reasons, as lobster flesh deteriorates rapidly after death, and partly for culinary preference, as pre-killed lobsters were thought to yield tougher meat. When placed in boiling water, lobsters exhibit behaviors that appear distressing: they thrash their tails, claw at the sides of the pot, and their heart rates increase dramatically. These responses have raised serious welfare concerns.

The process of death by boiling can take up to 45 seconds or longer, during which time the lobster may experience significant distress if capable of feeling pain. This has prompted researchers and chefs to develop more humane methods. Electrical stunning devices can render lobsters unconscious before cooking, while the “chilling” method involves placing lobsters in cold water that is gradually brought to boiling temperature, supposedly inducing a state of unconsciousness. However, the efficacy of these alternative methods in preventing suffering remains contested, with some experts arguing that only instant killing methods can truly eliminate potential suffering.

The Philosophical Dimensions of the Debate

The lobster sentience debate extends beyond scientific questions into philosophical territory concerning how we determine which beings deserve moral consideration. Philosophers like Peter Singer have argued that the capacity to suffer, not cognitive capabilities like self-awareness or rationality, should be the primary criterion for moral consideration. Under this utilitarian view, if lobsters can experience pain—even in a primitive form—their suffering should count in our moral calculations.

Others argue from a precautionary principle standpoint: given scientific uncertainty about lobster sentience, we should err on the side of caution and avoid potentially causing suffering. This approach doesn’t require definitive proof of lobster sentience but acknowledges that enough evidence exists to warrant ethical concern. Conversely, some philosophers and traditionalists maintain that moral consideration should be extended primarily to beings with higher cognitive functions, arguing that while compassionate treatment of all animals is desirable, equating lobster experiences with mammalian suffering inappropriately anthropomorphizes these creatures and devalues human moral experience.

Chefs and Restaurateurs Respond

The culinary world has been forced to grapple with the ethical implications of lobster preparation as awareness of potential crustacean sentience has grown. Some renowned chefs have taken decisive action. Heston Blumenthal, the chef behind The Fat Duck, discontinued serving lobster after becoming convinced of their capacity to suffer. Similarly, Alexis Gauthier of Gauthier Soho in London has removed all animal products, including lobster, from his menu, citing ethical concerns about animal welfare.

ther chefs have adopted compromise positions, continuing to serve lobster but adopting more humane killing methods. Chef Eric Ripert of Le Bernardin in New York uses a device called the Crustastun, which electrically stuns lobsters before cooking. Many restaurants now use the “knife method,” quickly severing the lobster’s central nerve cord before cooking. These adaptations reflect a growing recognition within the culinary community that traditional cooking methods may pose ethical problems, even as lobster remains a staple on many fine dining menus. The industry’s response demonstrates that commercial interests and ethical considerations need not be mutually exclusive.

Cultural and Religious Perspectives

Attitudes toward lobster consumption and preparation vary widely across cultures and religious traditions. In Judaism, lobsters are not kosher because they lack fins and scales, criteria for permitted seafood under Jewish dietary laws. This prohibition predates any ethical concerns about sentience. Similarly, some Buddhist traditions discourage the consumption of lobsters based on the principle of non-violence (ahimsa) and the belief that all sentient beings deserve compassion.

Indigenous coastal communities often have long-standing traditions of lobster harvesting that incorporate respect for marine life alongside sustainable consumption practices. For example, some Native American tribes performed rituals thanking lobsters for their sacrifice before harvesting them. These diverse cultural and religious perspectives remind us that the question of whether lobsters should be food or respected as sentient beings has been answered differently across human societies long before the current scientific debate began, suggesting that our ethical relationship with these creatures has always been more complex than modern industrial food systems might indicate.

The Neurobiological Evidence

Examining lobster neurobiology provides crucial insights into their potential for sentience. Though lobsters lack a centralized brain, they possess approximately 100,000 neurons—far fewer than humans’ 86 billion, but comparable to insects whose capacity for basic forms of learning and pain perception is increasingly recognized. Research has demonstrated that lobsters have complex sensory systems, including chemoreceptors that detect chemicals, mechanoreceptors sensitive to touch and water movement, and statocysts that help with orientation.

Studies have also shown that lobsters can learn to avoid unpleasant stimuli. In one experiment, lobsters quickly learned to avoid areas where they received mild electric shocks, demonstrating not just reflexive responses but associative learning capabilities. They also show preference behaviors, choosing environments with certain characteristics over others, suggesting they have subjective experiences. While lobsters clearly don’t possess consciousness comparable to mammals, the neurobiological evidence suggests they have more sophisticated neural processing than previously thought, capable of supporting some form of subjective experience that could include pain.

The Economic Impact of Changing Perspectives

The shift in perspective regarding lobster sentience has significant economic implications. The global lobster industry is valued at approximately $5.7 billion annually, with the American lobster fishery alone worth over $1 billion. Any regulations limiting traditional harvesting or cooking methods could substantially impact these industries and the communities that depend on them. In Maine, where lobstering represents a cultural heritage as well as an economic driver, concerns about new welfare regulations have been met with resistance from industry representatives who worry about added costs and operational challenges.

However, economic adaptation is possible. Premium “humanely harvested” lobster products have emerged in some markets, commanding higher prices from ethically conscious consumers. Companies like Clearwater Seafoods have invested in technology that processes lobsters more humanely while maintaining quality, suggesting that welfare improvements and economic viability can coexist. The industry may also benefit from improved consumer perception as it adopts more humane practices. Nevertheless, the transition period poses genuine economic challenges, particularly for smaller operations with limited capital to invest in new equipment or processing methods.

Scientific Uncertainty and the Burden of Proof

A central challenge in the lobster sentience debate is determining where the burden of proof should lie amid scientific uncertainty. Those arguing that lobsters deserve welfare protections often invoke the precautionary principle: given evidence suggesting lobsters may experience pain, we should act to prevent potential suffering until proven unnecessary. This approach holds that we needn’t wait for absolute certainty before extending moral consideration to these creatures, particularly when the potential harm (unnecessary suffering) is significant.

Skeptics counter that the burden should fall on those claiming lobsters are sentient, arguing that without definitive proof, we risk imposing costly regulations and cultural changes based on anthropomorphic projections rather than biological reality. They point to fundamental differences between crustacean and vertebrate nervous systems and the challenges of inferring subjective experiences in creatures so unlike ourselves. The scientific community continues to develop more sophisticated methods for assessing pain and sentience in non-human animals, but consensus remains elusive. This uncertainty creates a space where values and risk assessment inevitably influence how we interpret available evidence.

Alternative Approaches to Lobster Consumption

As the debate over lobster sentience continues, various stakeholders have developed alternative approaches to traditional consumption. Lab-grown seafood companies like BlueNalu and Shiok Meats are working to develop cellular aquaculture technologies that could eventually produce lobster meat without harvesting living creatures. These technologies, though still in early stages for complex seafood like lobster, promise to eliminate welfare concerns entirely while potentially offering environmental benefits through reduced fishing pressure and transportation emissions.

For those who continue to consume lobster, welfare-centered harvesting and preparation methods have gained traction. The North American Lobster Sustainability Alliance has developed best practice guidelines that include more humane handling and rapid killing techniques. Some processors now use high-pressure processing systems that kill lobsters instantly while preserving meat quality. Consumers increasingly have options that align with various ethical positions, from plant-based lobster alternatives made from hearts of palm or artichokes to certified humanely harvested lobster products. These alternatives demonstrate that ethical concerns about lobster sentience need not create a binary choice between traditional consumption and complete abstention.

The debate over whether lobsters are merely food or sentient beings deserving of moral consideration reflects a broader societal reckoning with our relationship to non-human animals. As scientific evidence continues to accumulate suggesting lobsters possess at least basic forms of sentience, we find ourselves at an ethical crossroads that demands thoughtful navigation. The path forward likely involves balancing respect for cultural traditions and economic realities with evolving understanding of animal consciousness and welfare. Perhaps most importantly, this debate challenges us to examine the arbitrary lines we draw between species we protect and those we consume, pushing us toward more consistent and compassionate ethical frameworks for all creatures capable of suffering.

- The Fish That Builds Nests - August 23, 2025

- The Insect That Ices Itself - August 23, 2025

- 15 Weirdest Things Fish Can Do - August 23, 2025