Deep within the world’s tropical forests, a remarkable evolution is taking place. Parrots, known for their vibrant colors and impressive vocal abilities, are adapting their communication methods in response to changing environments. These highly intelligent birds, belonging to the order Psittaciformes, have always been exceptional communicators, but recent research reveals fascinating shifts in how wild parrots interact with each other and their surroundings. From developing new calls to adjusting to urban environments, these adaptations showcase the remarkable plasticity of parrot communication systems and raise important questions about avian intelligence, evolution, and conservation.

The Foundation of Parrot Communication

Parrots have evolved complex communication systems that include a diverse repertoire of vocalizations, body language, and visual displays. Unlike most birds that are limited to a fixed set of genetically programmed calls, parrots are vocal learners—they acquire their vocalizations by listening to and imitating others. This remarkable ability, shared only with humans, some marine mammals, and a few other bird groups, allows parrots to develop regional dialects, adapt to new environments, and even learn new languages. In the wild, parrot communication serves multiple purposes: maintaining social bonds, coordinating group movements, warning about predators, establishing territories, and facilitating mate selection. This sophisticated foundation has positioned parrots perfectly to adapt their communication strategies as their environments change.

Environmental Pressures Driving Communication Changes

Several environmental factors are forcing wild parrots to modify how they communicate. Habitat fragmentation due to deforestation splits populations and interrupts traditional transmission of calls between generations. Noise pollution from urbanization masks natural sounds, making traditional calls less effective. Climate change alters breeding seasons and migration patterns, requiring new coordination signals. Additionally, the introduction of invasive species creates novel competitive and predatory pressures. These challenges require parrots to adapt quickly, and their vocal learning abilities provide the flexibility needed to survive in rapidly changing landscapes. Researchers have documented these adaptive changes across multiple species and continents, revealing a global pattern of communication evolution in wild parrot populations.

Urban Adaptations: Louder and Higher-Pitched Calls

Perhaps the most well-documented change in parrot communication comes from urban environments, where background noise presents a significant challenge. Studies of yellow-naped Amazons in Costa Rica and rainbow lorikeets in Australia have found that urban populations consistently produce louder, higher-pitched calls than their forest-dwelling counterparts. This adaptation allows their vocalizations to cut through the low-frequency noise of traffic and machinery. Researchers at Cornell University discovered that urban-dwelling parrots also tend to call during quieter periods of the day, demonstrating remarkable behavioral flexibility. Some species have even developed shorter, more punctuated calls that are more easily distinguished amid city clamor. These adaptations demonstrate not only the parrots’ cognitive abilities but also highlight the remarkable plasticity of their vocal apparatus, which allows them to modify sound production in response to environmental pressures.

The Development of Regional Dialects

As parrot populations become increasingly isolated due to habitat fragmentation, distinct regional dialects are emerging. A groundbreaking study of yellow-naped Amazons in Costa Rica revealed that populations separated by just 25 kilometers developed noticeably different contact calls. These dialects serve as cultural markers that identify group membership and may even influence mate selection. Similar patterns have been observed in Australian galahs and New Zealand keas. The process resembles how human languages diverge over time when communities become separated. What makes this particularly fascinating is that younger parrots seem to adopt the local dialect rather than maintaining their parents’ calls, suggesting cultural transmission rather than genetic inheritance. This cultural evolution of communication systems provides a unique window into how language-like systems develop and change over time in non-human species.

Novel Vocalizations for Novel Threats

Wild parrots are developing new alarm calls in response to emerging threats in their environments. Researchers tracking Cape parrots in South Africa documented the emergence of distinctive alarm calls specifically for warning about new predators that have expanded their range due to climate change. Similarly, Australian cockatoos have developed specialized calls that alert flocks to the presence of introduced predators like feral cats and foxes—threats they didn’t encounter historically. These new vocalizations spread rapidly through populations, demonstrating social learning. The specificity of these calls is remarkable—they often contain acoustic elements that indicate the type of threat, its proximity, and even its behavior. This sophisticated referential communication system allows for appropriate response strategies, highlighting the cognitive complexity underpinning parrot communication adaptation.

Interspecies Communication Adaptations

One of the most surprising developments is how some wild parrot species are adapting to communicate with other species. In mixed-species foraging groups in the Amazon, macaws and Amazon parrots have been observed modifying their calls to facilitate coordination with other parrot species. This interspecies communication improves foraging efficiency and predator detection. Research in Australian ecosystems reveals that some cockatoo species have developed calls that attract honeyeaters to rich food sources, creating mutually beneficial relationships. Even more remarkably, some wild African grey parrots appear to mimic the alarm calls of local monkeys, potentially to benefit from the primates’ vigilance. These adaptations suggest that parrots recognize the value of communication beyond their own species and can strategically modify their vocalizations to engage in complex ecological relationships.

Technology-Influenced Communication Changes

Human technology is influencing wild parrot communication in unexpected ways. Researchers in Australia have documented wild cockatoos incorporating ringtones, car alarms, and construction sounds into their natural repertoire. In South America, some wild Amazon parrots living near research stations have been observed mimicking the beeping sounds of scientific equipment. While mimicry has always been part of parrot behavior, what’s noteworthy is how these sounds are being incorporated into functional communication. Some researchers hypothesize that these novel sounds may attract attention more effectively in certain contexts or serve as distinctive markers for specific territories. This phenomenon highlights the dynamic relationship between human-generated soundscapes and wild animal communication, raising questions about how our technologies might be inadvertently reshaping animal behavior in ways we’ve only begun to understand.

The Role of Vocal Learning in Adaptation

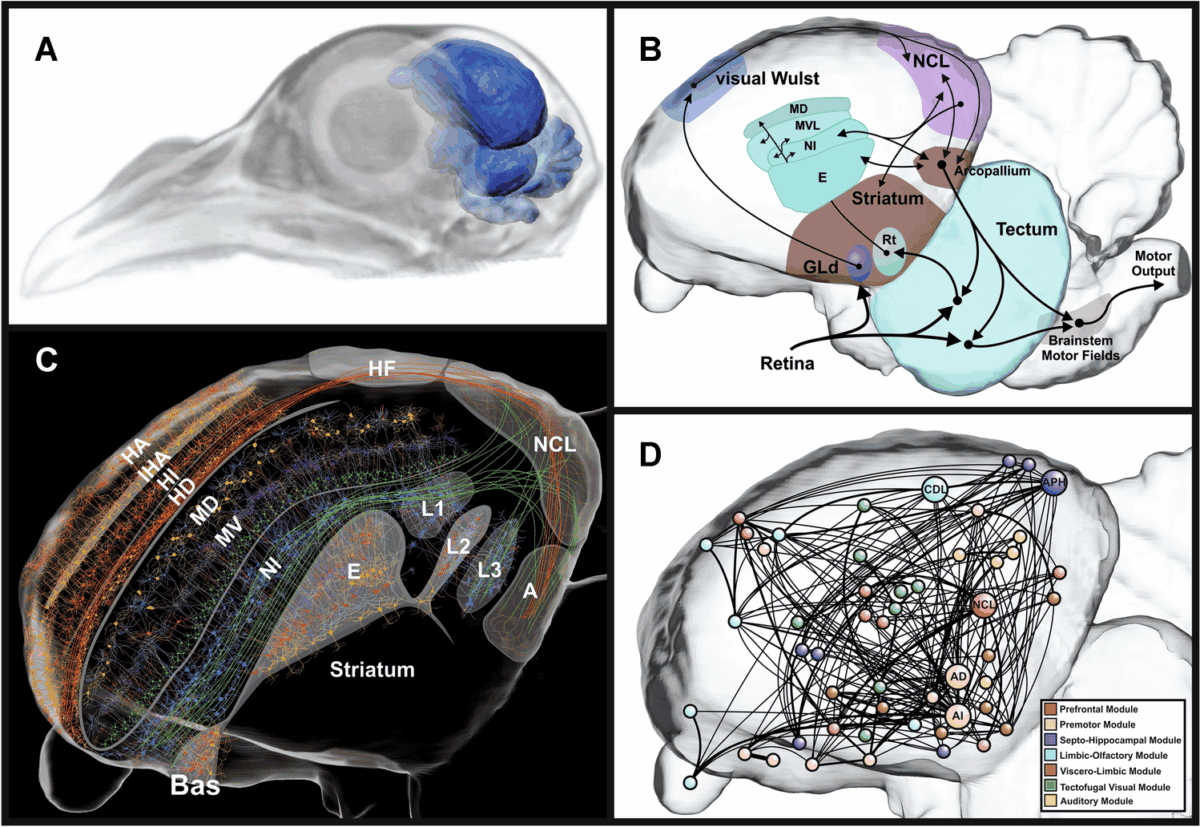

The remarkable vocal learning abilities of parrots underpin their communication adaptations. Unlike most birds, parrots possess a specialized brain circuit dedicated to vocal learning—the anterior forebrain pathway—which bears striking similarities to human speech learning pathways. This neural architecture allows parrots to continuously modify their vocalizations throughout their lives. Recent neurobiological studies reveal that exposure to environmental changes activates plasticity in these brain regions, facilitating rapid adaptation of communication patterns. Young parrots appear particularly responsive, with critical periods for vocal learning that can be extended or reactivated during environmental shifts. The parrots’ capacity to learn new vocalizations into adulthood provides an evolutionary advantage in changing environments. This neurological flexibility represents a fascinating example of convergent evolution with humans and offers insights into how vocal learning systems evolve and adapt.

Social Complexity and Communication Evolution

The social structures of wild parrot flocks significantly influence how their communication systems evolve. Parrots typically live in complex social groups with long-term pair bonds and extended family relationships. As environmental pressures force changes in group size, composition, and dynamics, communication patterns adapt accordingly. Researchers studying scarlet macaws in Peru found that populations living in fragmented forests developed more complex contact calls that contained more individual-specific information compared to those in continuous forests. This adaptation appears to help maintain group cohesion when visual contact is limited. Similarly, yellow-crowned Amazons in fragmented habitats have developed more frequent call-and-response patterns that help coordinate group movements across gaps in the forest canopy. These adaptations highlight how communication evolution is shaped not just by physical environment but also by the social context in which communication occurs.

Conservation Implications of Communication Changes

The changing communication patterns of wild parrots have significant conservation implications. As parrots develop region-specific dialects, releasing captive-bred individuals into the wild becomes more complicated—they may lack the appropriate vocalizations to integrate successfully into wild flocks. Conservation efforts now increasingly include “cultural training” where captive parrots are exposed to recordings of wild calls before release. Additionally, communication changes can serve as early warning systems for environmental degradation. Sudden shifts in call structure or timing may indicate environmental stressors before other effects become visible. For critically endangered species like the Spix’s macaw, preserving recordings of wild calls has become an essential part of conservation programs. Understanding how communication systems adapt also helps conservation planners predict how species might respond to future environmental changes, informing more effective protection strategies.

Human Impact on Parrot Communication

Human activities are primary drivers of changes in parrot communication. Beyond noise pollution and habitat fragmentation, human activities create other significant pressures. The illegal wildlife trade removes vocal role models from wild populations, potentially disrupting cultural transmission of communication patterns. Introduced predators force the development of new alarm calls. Agricultural expansion creates novel food sources that require new coordination signals. Even well-intentioned conservation interventions, such as supplementary feeding stations, can alter social dynamics and communication needs. However, human impact isn’t universally negative. Some parrot species thrive in human-modified landscapes, developing innovative communication strategies to exploit new resources. For instance, sulphur-crested cockatoos in Australia have developed calls specifically used to coordinate raids on agricultural fields and to alert others when humans approach. These complex interactions between human activities and parrot communication highlight the need for interdisciplinary approaches to conservation that consider behavioral adaptations alongside traditional protection measures.

Future Research Directions

The study of changing parrot communication represents a vibrant frontier in animal behavior research. Emerging technologies like miniature audio recorders, machine learning algorithms for call analysis, and remote monitoring systems are enabling more comprehensive studies of wild parrot communication than ever before. Researchers are developing acoustic monitoring networks that can track communication changes across entire populations over time, providing unprecedented insight into how these systems evolve. Future studies aim to investigate whether communication changes represent evolutionary adaptations or flexible responses that can be reversed, how vocal learning is maintained across generations despite environmental disruptions, and whether some parrot species are more adaptable than others. Cross-species comparisons with other vocal learners like dolphins and humans may yield insights into the general principles governing communication adaptation. These research directions not only advance our understanding of animal communication but may also inform conservation strategies and provide insights into the evolution of human language.

The evolving communication systems of wild parrots reveal the remarkable adaptability of these intelligent birds in the face of environmental change. Through vocal learning, social transmission, and cognitive flexibility, parrots around the world are developing new calls, adjusting acoustic parameters, and establishing novel communication patterns to meet the challenges of their changing habitats. These adaptations not only highlight the cognitive sophistication of parrots but also offer valuable lessons for conservation, demonstrating how behavioral flexibility can contribute to species resilience. As human influence on natural environments continues to expand, understanding how animal communication systems respond becomes increasingly important for effective conservation planning. The story of changing parrot communication reminds us that nature’s response to environmental challenges can be both creative and complex, involving not just physical adaptations but cultural and behavioral innovations that may ultimately determine which species thrive in our rapidly changing world.

- What Horses Teach Us About Nonverbal Communication - August 25, 2025

- How a Breed’s Adaptability Fits Frequent Moves - August 25, 2025

- Meet the World’s Heaviest Flying Bird - August 25, 2025