Few extinct creatures capture the human imagination quite like the dodo bird. This flightless avian, once native to the island of Mauritius, has transcended its biological significance to become a powerful symbol of human-caused extinction and a cautionary tale of environmental stewardship. The dodo’s journey from thriving island dweller to extinction in less than a century represents one of the most rapid and well-documented disappearances of a species in human history. Despite never having been extensively studied in life, the dodo has achieved an almost mythical status in death, becoming synonymous with obsolescence and serving as a stark reminder of humanity’s impact on vulnerable species. This article explores the remarkable story of the dodo bird—from its evolutionary origins and unique characteristics to its tragic demise and enduring legacy in science, culture, and conservation.

The Evolutionary Origins of the Dodo

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) evolved from flying pigeons that arrived on the isolated island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean approximately 8 million years ago. Through the process of allopatric speciation, these ancestral birds gradually adapted to the island environment, where abundant food sources and an absence of mammalian predators eliminated the necessity for flight. Genetic studies conducted on preserved dodo specimens confirm its closest living relative is the Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica), a colorful bird still found across Southeast Asia and the Pacific. This evolutionary relationship places the dodo within the Columbidae family, making it essentially a giant, specialized pigeon. The dodo’s evolution represents a classic example of island gigantism, a phenomenon where species isolated on islands with limited competition and predation often grow larger than their mainland counterparts. Through adaptations spanning millions of years, the dodo developed its distinctive characteristics, perfectly suited to its island paradise—until human arrival changed everything.

Physical Characteristics: The Reality Behind the Myth

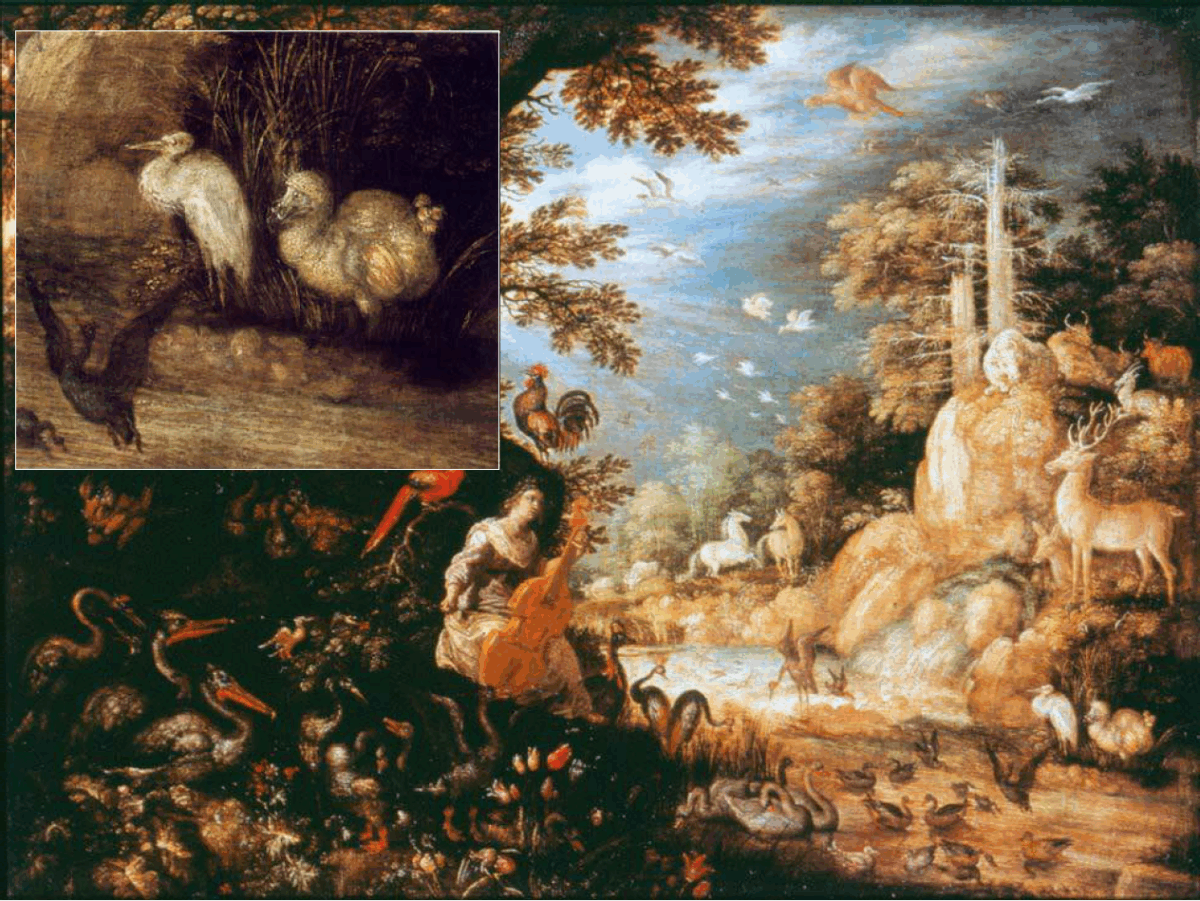

Despite its fame, our understanding of the dodo’s true appearance has been compromised by often inaccurate historical illustrations and a limited fossil record. Modern scientific reconstructions suggest the dodo stood approximately 3 feet (1 meter) tall and weighed between 23-39 pounds (10-18 kg), considerably less than earlier exaggerated accounts. The bird possessed a large, hooked beak that was likely greenish-yellow, sturdy legs designed for walking rather than running, and small, vestigial wings incapable of flight. Its plumage was likely gray to brownish-gray, rather than the vibrant colors depicted in some historical paintings. The dodo’s most distinctive feature was its disproportionately large head with the substantial beak adapted for its specialized diet. Contemporary scientific analysis of skeletal remains indicates the dodo was not the awkward, obese creature of popular imagination, but rather a well-adapted island bird with a physiology suited to its ecological niche. Recent research suggests it had relatively good eyesight, a well-developed sense of smell, and was likely more agile than traditionally portrayed in historical accounts and cultural depictions.

Life on Mauritius: The Dodo’s Island Paradise

Prior to human arrival, Mauritius provided the dodo with an ideal habitat free from natural predators. The island’s diverse ecosystem featured dense forests, wetlands, and coastal areas that supported a rich biodiversity perfectly suited to the dodo’s needs. The bird established a unique ecological niche, feeding primarily on fruits, seeds, nuts, and possibly small invertebrates found on the forest floor. Paleontological evidence suggests the dodo played a crucial role in forest regeneration through seed dispersal, particularly for the tambalacoque tree (Sideroxylon grandiflorum), once thought to depend entirely on the dodo for propagation. The dodo’s daily routine likely involved foraging during cooler morning and evening hours while sheltering from the midday heat. Although social behaviors remain largely speculative, fossil evidence of multiple specimens found in close proximity suggests some degree of social living. The isolated nature of Mauritius allowed the dodo to evolve without developing natural fear responses or defensive mechanisms against predators, a factor that would ultimately contribute to its vulnerability when humans arrived on the island in the late 16th century.

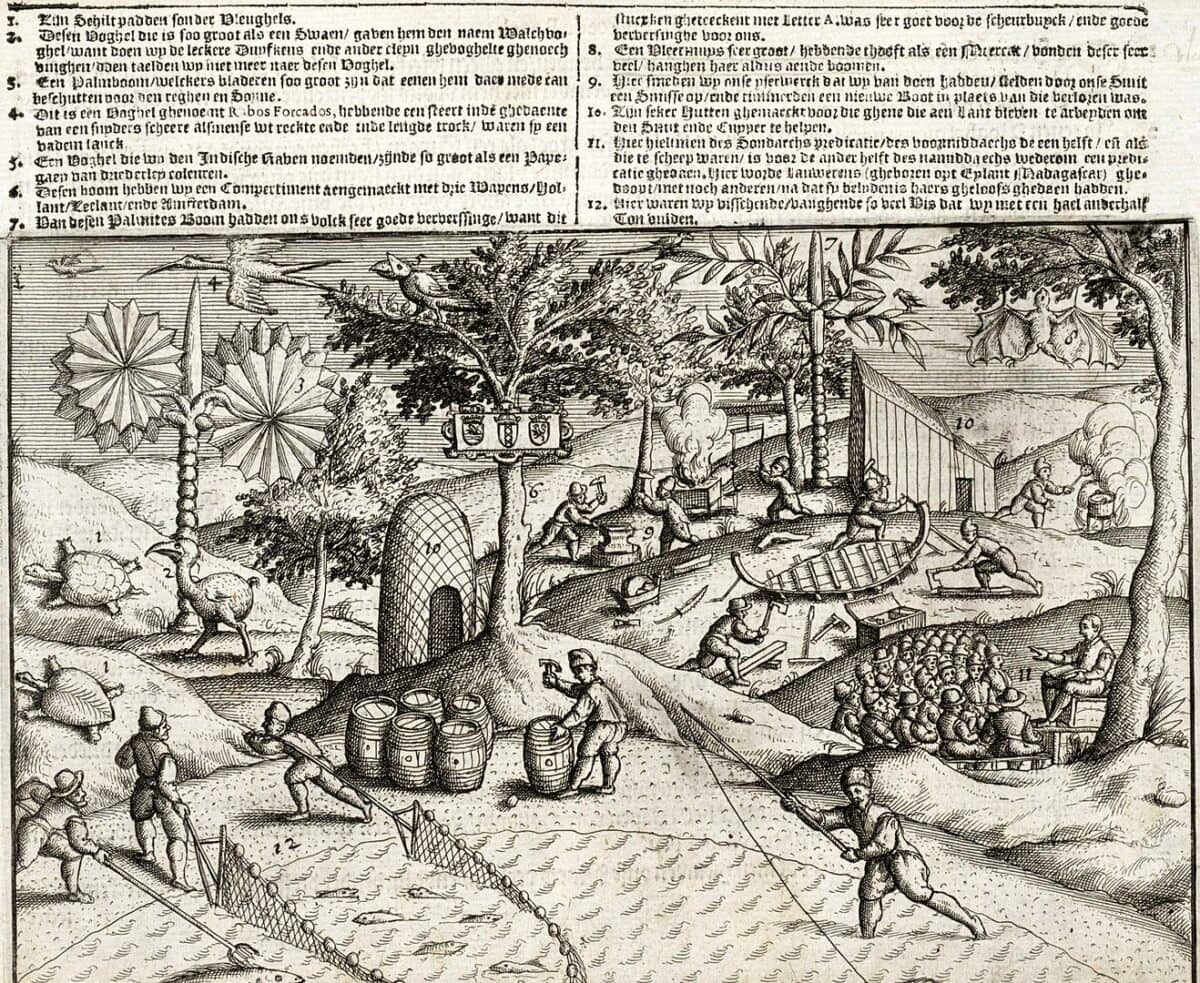

First Contact: Human Discovery of the Dodo

The first documented human encounter with the dodo occurred when Dutch sailors landed on Mauritius in 1598, during the height of European maritime expansion. Admiral Jacob Cornelius van Neck and his crew provided the earliest written accounts of this unusual bird, which they initially called “walghvogel” (meaning “disgusting bird” or “tasteless bird”) due to its reportedly unpalatable meat. These early Dutch mariners were astonished by the bird’s lack of fear toward humans, as the dodo approached sailors with curiosity rather than caution. This naive behavior, evolved in the absence of predators, would prove fatal for the species. Several live dodos were transported to Europe as curiosities for wealthy collectors and menageries, though none survived long in captivity. These initial encounters were documented in ships’ logs and illustrated in journals, providing valuable but often exaggerated or inaccurate depictions of the bird. The dodo quickly became a subject of fascination among European naturalists, though scientific understanding of the species remained limited. These first contacts between humans and dodos marked the beginning of a brief but catastrophic relationship that would lead to the bird’s extinction within less than a century.

The Rapid Decline: Factors Leading to Extinction

The dodo’s extinction resulted from a perfect storm of destructive factors introduced by human colonization. While direct hunting played a role, contrary to popular belief, it wasn’t the primary cause of the dodo’s demise. More devastating was the introduction of invasive species—rats, pigs, monkeys, and other mammals—that escaped from ships or were deliberately released, quickly establishing feral populations on the island. These non-native animals preyed voraciously on dodo eggs and nestlings, decimating the bird’s reproductive success. Simultaneously, human settlers cleared large tracts of forest for agriculture and timber, destroying critical dodo habitat. The dodo’s slow reproductive rate, with females likely laying just one egg per season, made population recovery impossible against these combined pressures. The species’ lack of fear toward humans also made them exceptionally easy targets for hunters and predators alike. Within just 65-80 years of human discovery, the last dodo perished. The most commonly accepted extinction date is 1662, based on the last reliable account by Volquard Iversen, though some researchers suggest a slightly later date. This extraordinarily rapid extinction represents one of the first documented cases of a species disappearing entirely due to human activities.

Scientific Uncertainty: Dating the Dodo’s Disappearance

Determining the exact date of the dodo’s extinction has proven challenging for scientists and historians. The last widely accepted sighting comes from the journal of Volquard Iversen, who reported encountering dodos on Mauritius in 1662. However, some accounts claim sightings as late as the 1680s, though these reports lack reliable verification. The challenge in establishing a definitive extinction date stems from several factors: declining dodo populations would have become increasingly difficult to observe; documentation from the period is incomplete; and early naturalists lacked standardized methods for recording observations. Adding to the complexity, early accounts sometimes confused dodos with other flightless birds from neighboring islands. Modern scientific consensus generally places the extinction between 1662 and 1690, making it one of the fastest documented extinctions in history. Recent archaeological excavations at Mare aux Songes in Mauritius have unearthed numerous dodo remains, helping scientists refine extinction timeline estimates through carbon dating and stratigraphic analysis. The relatively brief period between discovery and extinction—spanning less than a century—underscores the devastating speed with which human activity can eliminate an entire species.

The Forgotten Bird: Post-Extinction Obscurity

Following its extinction, the dodo fell into a period of scientific obscurity that lasted nearly two centuries. By the mid-18th century, many naturalists began questioning whether the dodo had ever existed at all, dismissing earlier accounts as sailors’ exaggerations or misidentifications of known species. This skepticism was fueled by the scarcity of preserved specimens—only fragmentary remains existed in European collections, with no complete taxidermy specimens surviving. The situation changed dramatically in 1865 when schoolteacher George Clark discovered a substantial cache of dodo bones in the marshlands of Mare aux Songes in Mauritius. This discovery provided tangible proof of the bird’s existence and sparked renewed scientific interest. During this period of obscurity, several dodo specimens were actually destroyed, most notably at Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum, where a deteriorating stuffed dodo was burned in 1755, with only the head and one foot preserved. The London Museum lost another rare specimen to decay, highlighting the era’s limited understanding of preservation techniques and taxonomic importance. This period of neglect and skepticism significantly hampered scientific understanding of the species and resulted in the loss of potentially valuable specimens that might have provided greater insights into dodo biology and behavior.

Cultural Immortality: The Dodo in Literature and Art

Despite its physical extinction, the dodo achieved immortality through its prominent place in literature, art, and popular culture. The bird’s most famous literary appearance comes in Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” (1865), where the Dodo organizes the “Caucus Race” and speaks with strange dignity. This characterization, published coincidentally the same year as Clark’s rediscovery of dodo remains, cemented the bird’s place in popular imagination. The dodo has since appeared in countless works, from Salvador Dalí’s surrealist paintings to works by Hilaire Belloc and poems by Hilaire Belloc. The bird’s name entered common language as an idiom for obsolescence—”dead as a dodo”—reflecting its status as the quintessential extinct creature. Museums worldwide feature dodo reconstructions, with the Natural History Museum in London housing one of the most famous displays. In Mauritius, the dodo appears on the national coat of arms, currency, and as a common motif in tourism materials, becoming an unofficial national symbol. This cultural afterlife transformed the dodo from merely an extinct species into a powerful metaphor for extinction itself. Through artistic representation, the dodo paradoxically achieved greater fame and recognition after its demise than during its existence, ensuring that this flightless bird would never be forgotten.

Scientific Legacy: What We’ve Learned from the Dodo

The dodo has made significant contributions to scientific understanding despite having disappeared before modern scientific methods could study it in life. The species played a pivotal role in the development of extinction theory—prior to the confirmation of the dodo’s disappearance, many Western scientists and natural philosophers believed that species extinction was impossible, contradicting divine creation. The indisputable evidence of the dodo’s extinction helped establish extinction as a biological reality, directly influencing Georges Cuvier’s pioneering work on extinction theory in the early 19th century. In modern times, the dodo continues to yield scientific insights through advanced techniques. DNA extraction from preserved specimens has allowed researchers to confirm its taxonomic placement within the pigeon family and reconstruct aspects of its evolutionary history. Three-dimensional scanning of skeletal remains has enabled more accurate reconstructions of the dodo’s appearance, movement capabilities, and sensory abilities, challenging many long-held misconceptions. Perhaps most importantly, study of the dodo has advanced understanding of island biogeography, demonstrating how isolation shapes evolutionary processes and highlighting the vulnerability of island species to invasive organisms and habitat modification. The dodo thus serves as both a historical specimen and an ongoing subject of scientific inquiry, contributing to biological knowledge centuries after its extinction.

Modern Reconstructions: Picturing the Real Dodo

Contemporary scientific efforts have dramatically revised our understanding of what the dodo actually looked like, debunking many misconceptions perpetuated through centuries of inaccurate depictions. Modern reconstructions utilize advanced techniques including CT scanning of rare skeletal specimens, comparative anatomy with related living species, and biomechanical modeling to create more accurate representations. These scientific reconstructions reveal a bird considerably different from the obese, awkward creature of popular imagination. The dodo likely had a more streamlined body with proportions similar to modern ground-dwelling pigeons, though significantly larger. Its wings, while vestigial, were probably more developed than typically portrayed. Analysis of the dodo’s brain cavity suggests it possessed cognitive abilities and sensory adaptations comparable to other columbiform birds. The dodo’s beak structure, long thought to be primarily a weak, specialized tool for fruit consumption, has been reinterpreted as potentially more versatile and stronger than previously believed. Pioneering work by paleontologist Julian Hume and paleoartist Katrina van Grouw has produced what experts consider the most accurate visual reconstructions to date, based on comprehensive analysis of all available evidence. These revised visuals present the dodo as a well-adapted, successful island species rather than the awkward evolutionary failure of popular mythology, significantly changing our perception of this iconic bird.

De-extinction Debates: Could We Bring Back the Dodo?

The dodo has emerged as a prime candidate in ongoing discussions about de-extinction—the controversial concept of resurrecting extinct species through genetic technology. In January 2023, Colossal Biosciences, a Texas-based biotechnology company, announced a $150 million project aimed at bringing back the dodo through genetic engineering. Their approach involves extracting DNA fragments from preserved dodo specimens, sequencing the genome, and identifying genetic differences between dodos and their closest living relatives. The plan would utilize gene-editing techniques to modify the Nicobar pigeon genome to express dodo-like traits, essentially creating a hybrid with dodo characteristics. This proposal has generated extensive scientific debate. Proponents argue that de-extinction could advance genetic technologies, restore lost ecological functions, and provide powerful conservation lessons. Critics counter with numerous concerns: the resulting organism wouldn’t be a true dodo but a genetically modified approximation; the original habitat has been irreversibly altered; and limited resources might be better directed toward protecting critically endangered species. Ethical questions also arise regarding the welfare of the created animals and potential ecosystem impacts. While complete dodo resurrection remains technically unfeasible with current technology, the debate highlights complex questions at the intersection of conservation biology, genetic technology, ecology, and ethics. Whether or not the dodo ever returns in some form, these discussions are shaping our approach to biodiversity preservation and extinction.

Conservation Lessons: The Dodo’s Enduring Message

The dodo’s extinction story carries profound lessons that continue to influence modern conservation efforts worldwide. As perhaps the first well-documented human-caused extinction, the dodo serves as a powerful cautionary tale about the vulnerability of island ecosystems and species with limited geographic ranges. Conservation biologists frequently reference the dodo case when highlighting the devastating impact of invasive species on native wildlife—the introduced rats, pigs, and monkeys that contributed significantly to the bird’s demise represent a pattern repeated on islands globally. The rapid timeline of the dodo’s extinction, occurring within a single human lifetime, demonstrates how quickly human activities can eliminate unique species, particularly those that evolved without defenses against predators or competition. In direct response to lessons learned from the dodo and similar extinctions, modern conservation practices now prioritize biosecurity measures for islands, invasive species prevention and eradication programs, and special protections for evolutionarily isolated species. The dodo’s story has directly influenced the development of tools like the IUCN Red List criteria for evaluating extinction risk and shaped international agreements like the Convention on Biological Diversity. Perhaps most importantly, the dodo has become an accessible symbol that helps communicate complex biodiversity concepts to the public, transforming an abstract scientific concern into a compelling narrative that resonates widely. Through its absence, the dodo continues to shape how we protect the planet’s remaining biodiversity.

The Enduring Legacy of the Dodo

The dodo’s remarkable journey from obscure island bird to global symbol of extinction represents one of the most profound transformations in our relationship with wildlife. Though its physical existence was brief in human historical terms, its impact continues to reverberate through science, culture, and conservation centuries after its disappearance. As humanity faces unprecedented biodiversity loss in the modern era, the dodo’s story provides both a warning and inspiration—reminding us of our capacity to cause irreversible harm while simultaneously motivating efforts to prevent similar tragedies. The ongoing scientific investigations into dodo biology, the cultural representations that keep its memory alive, and the conservation principles derived from its extinction collectively ensure that this flightless bird maintains a unique place in human consciousness. Whether the dodo ever returns through genetic technology or remains forever in the realm of history, its legacy as the archetypal lost species endures, challenging each generation to consider what other remarkable creatures might vanish without adequate protection and understanding.

- America’s Most Endangered Mammals And How to Help - August 9, 2025

- The Coldest Town in America—And How People Survive There - August 9, 2025

- How Some Birds “Steal” Parenting Duties From Others - August 9, 2025