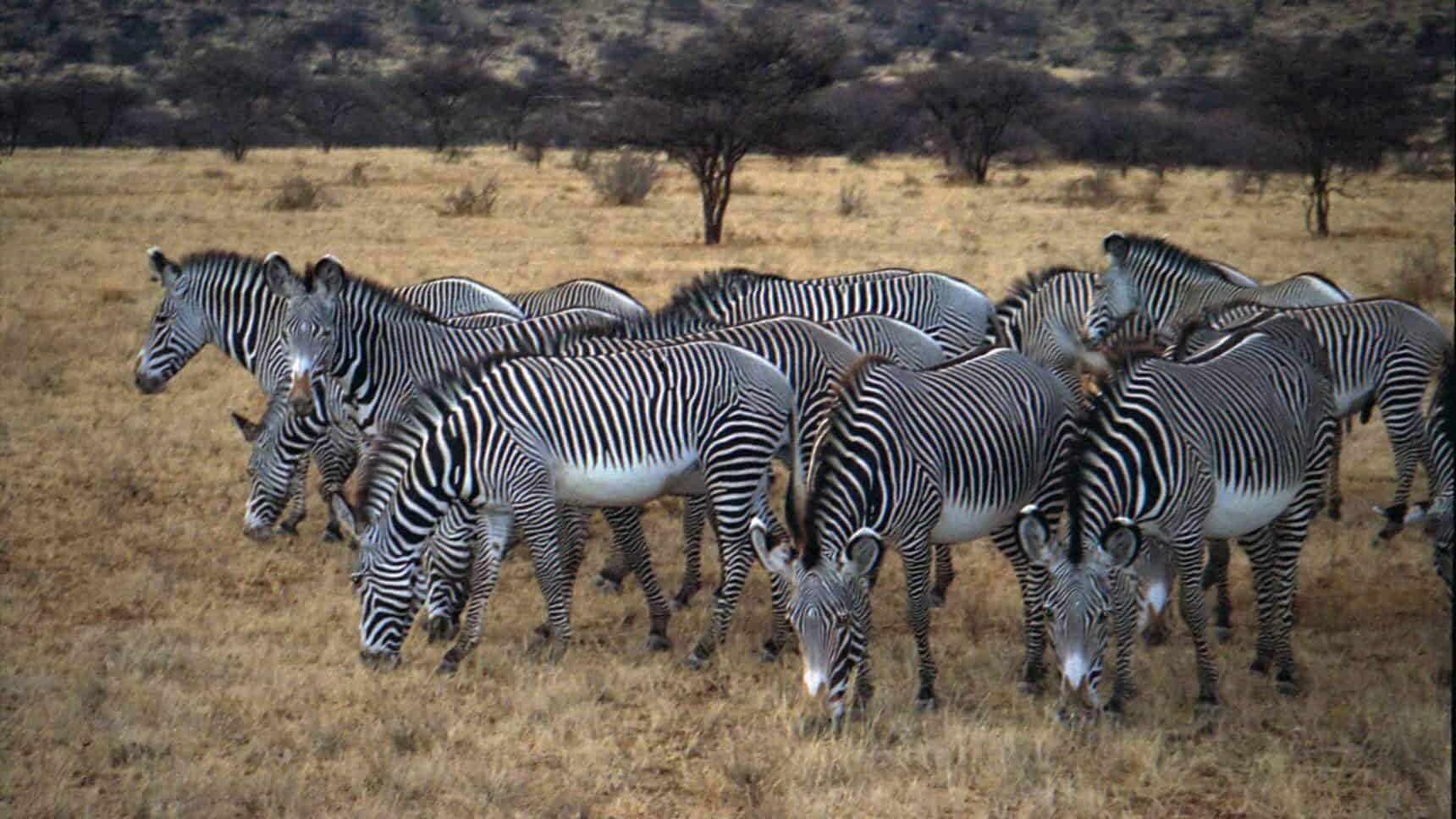

Zebras, with their distinctive black-and-white striped coats, are among Africa’s most recognizable mammals. These equids roam the savannas and grasslands of eastern and southern Africa, living in family groups or herds that can sometimes number in the hundreds. While many admire their striking appearance, fewer people understand the complex challenges these animals face in the wild—challenges that directly impact their lifespans. From predators to human encroachment, climate change to disease, wild zebras navigate numerous threats throughout their lives. This article explores how long zebras typically live in their natural habitat and examines the factors that influence their survival in an increasingly changing African landscape.

The Natural Lifespan of Wild Zebras

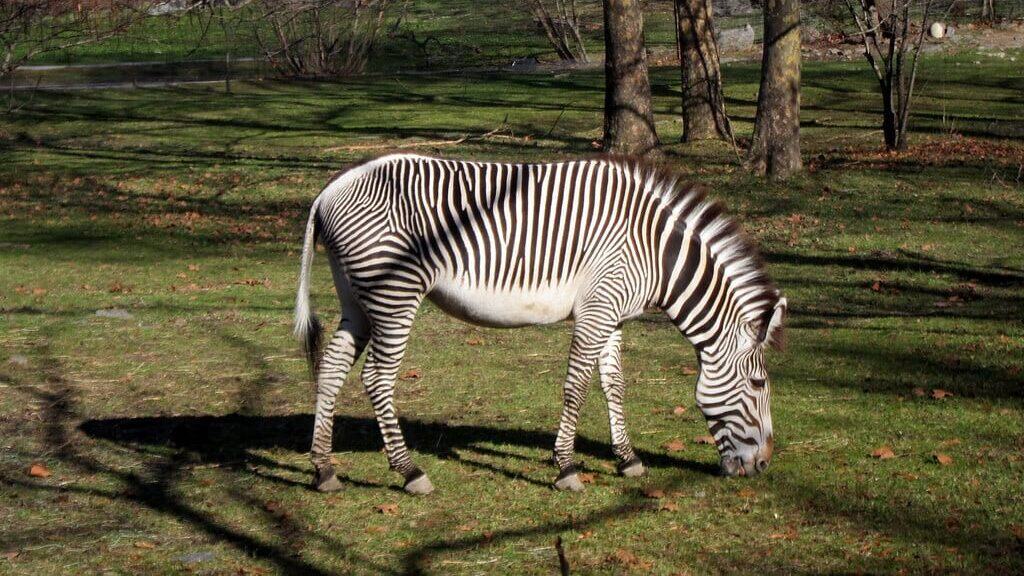

In the wild, zebras typically live between 20 to 25 years under optimal conditions. This lifespan is considerably shorter than what they might achieve in protected environments like wildlife sanctuaries or zoos, where they can live up to 40 years with regular veterinary care, consistent nutrition, and absence of predators. The three zebra species—Plains (Equus quagga), Mountain (Equus zebra), and Grevy’s (Equus grevyi)—have similar lifespans, though Grevy’s zebras tend to be slightly longer-lived when conditions permit.

A zebra’s life cycle begins with an 11-13 month gestation period, followed by a swift entry into the world where foals can stand within minutes and run within an hour—evolutionary adaptations crucial for survival in predator-rich environments. Young zebras remain dependent on their mothers for milk for up to 16 months, though they begin grazing within a few weeks of birth. Sexual maturity is reached between 3-6 years, with females generally maturing earlier than males. The prime reproductive years for zebras extend from approximately age 5 to 15, after which fertility gradually declines.

Predation: The Primary Natural Threat

Predation represents the most significant natural threat to wild zebras, particularly affecting the young and elderly. Lions are the foremost predators of adult zebras, with a pride often working together to isolate and bring down these swift ungulates. A single zebra kill can feed a pride for days, making them valuable prey despite the challenge they present. Other significant predators include spotted hyenas, which may hunt zebras in coordinated packs, and cheetahs and leopards, which typically target foals rather than full-grown adults.

Crocodiles pose a specific threat during river crossings, especially during the Great Migration in the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem, where thousands of zebras alongside wildebeest and gazelles cross crocodile-infested rivers. These dangerous crossings result in numerous casualties each year. African wild dogs and jackals may also opportunistically prey on young, sick, or injured zebras. Zebras have evolved several defensive strategies against predation, including their sharp vision, acute hearing, powerful kicks, and the protection offered by herd living, where multiple sets of eyes improve predator detection chances.

Habitat Loss and Fragmentation

One of the most pressing modern threats to zebra populations is habitat loss and fragmentation. As human populations grow across Africa, natural zebra habitats are increasingly converted to agricultural land, urban developments, and infrastructure projects. The World Wildlife Fund estimates that zebras have lost approximately 25% of their historical range across Africa due to human development. This loss is particularly acute for Mountain and Grevy’s zebras, which have more specialized habitat requirements than Plains zebras.

Habitat fragmentation compounds these challenges by dividing once-continuous populations into smaller, isolated groups. These fragmented populations face reduced genetic diversity, limited access to seasonal migration routes, and increased vulnerability to localized threats such as drought or disease outbreaks. Conservation efforts increasingly focus on establishing wildlife corridors to reconnect fragmented habitats, allowing zebras and other wildlife to move between protected areas. These corridors are vital for maintaining genetic exchange between isolated populations and enabling access to seasonal resources that zebras depend on throughout the year.

Climate Change and Drought

Climate change poses an escalating threat to wild zebra populations across Africa. Increasingly unpredictable rainfall patterns and more frequent, severe droughts directly impact water availability and the quality of grazing lands that zebras depend on. During prolonged droughts, zebras may be forced to travel longer distances between water sources and grazing areas, increasing their energy expenditure and exposure to predators. Young, elderly, and pregnant or nursing females are particularly vulnerable to these stressors.

The changing climate also alters vegetation patterns across zebra habitats. Some regions experience bush encroachment—where woody plants invade grasslands—reducing the open grazing areas that zebras prefer. Climate models predict that suitable habitat for all three zebra species will shift and potentially shrink in coming decades. For Mountain zebras, which already occupy restricted ranges in mountainous regions of South Africa and Namibia, climate change could push their habitat requirements beyond the available geographic space, creating what ecologists term “nowhere to go” scenarios that threaten long-term survival.

Human-Wildlife Conflict

As human settlements expand into traditional zebra territories, direct conflicts between people and zebras have increased. While zebras don’t pose the same threat to human life as predators like lions or elephants, they compete with livestock for grazing land and water resources—a significant concern in semi-arid regions where these resources are already limited. Zebras may also raid crops when their natural food sources become scarce, leading to retaliatory killings by farmers protecting their livelihoods.

In some regions, zebras face persecution due to competition with domestic horses and donkeys for grazing lands. This is particularly problematic for the endangered Grevy’s zebra in northern Kenya and Ethiopia, where pastoral communities maintain large herds of livestock. Conservation organizations increasingly work with local communities to develop sustainable land-use practices that accommodate both wildlife and domestic animals. Community-based conservation initiatives that provide economic incentives for protecting zebras and their habitats have shown promise in reducing conflict and fostering coexistence between people and wildlife.

Poaching and Illegal Hunting

While not targeted for ivory or horns like elephants and rhinos, zebras face significant pressure from poaching and illegal hunting. Zebras are hunted primarily for their distinctive skins, meat, and traditional medicine. In some regions, zebra meat is considered a delicacy or a source of protein in areas where food security is an issue. Their skins are highly valued in international markets, where they’re used for rugs, wall hangings, and fashion items. This commercial demand drives poaching, particularly in areas with limited anti-poaching enforcement.

The Grevy’s zebra, with fewer than 2,000 individuals remaining in the wild, is especially vulnerable to poaching pressure. Conservation efforts include increased anti-poaching patrols, community awareness programs about the ecological importance of zebras, and international agreements restricting the trade of zebra products. Some conservation groups also work with communities to develop alternative livelihood options that reduce dependence on bushmeat hunting. DNA testing of zebra products in markets has become an important tool for tracking illegal trade routes and targeting enforcement efforts.

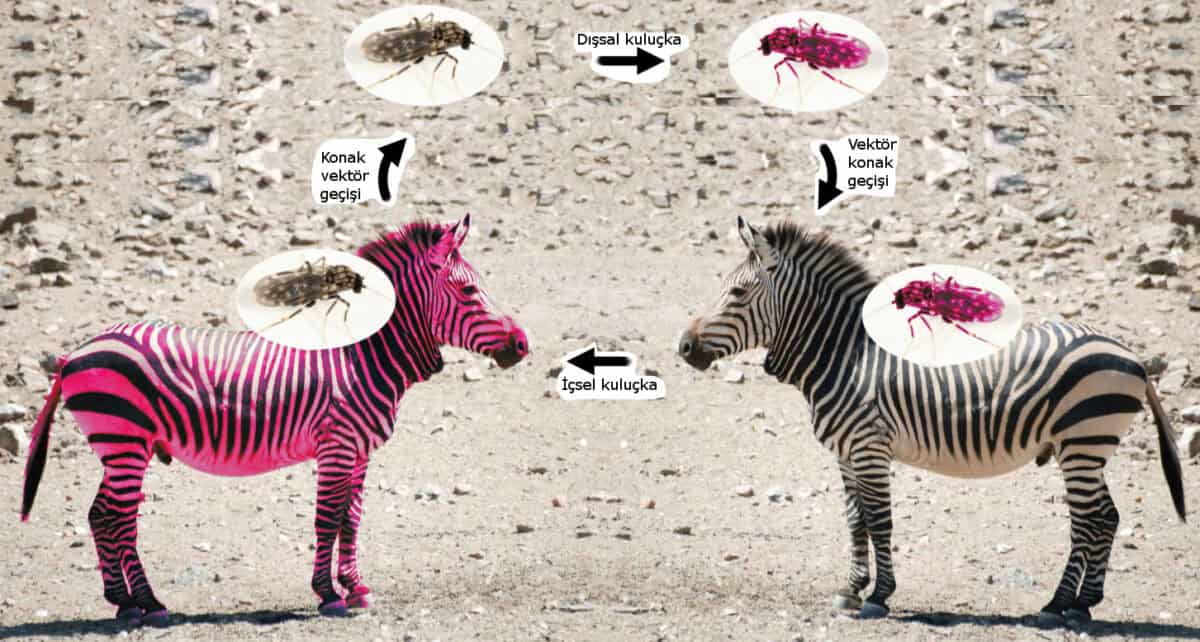

Disease and Health Challenges

Wild zebras face numerous health challenges that can significantly impact their lifespans. Anthrax, a bacterial disease that spreads through soil and vegetation, periodically affects zebra populations in parts of Africa, causing rapid death when contracted. Zebras are also susceptible to African horse sickness, a viral disease transmitted by biting midges that can cause mortality rates exceeding 90% in naive populations. Equine encephalosis, another insect-borne viral disease, affects zebras throughout their range with varying severity.

Parasitic infections also take a toll on zebra health and longevity. External parasites like ticks can transmit diseases and cause anemia through blood loss, while internal parasites such as strongyles (intestinal worms) can cause malnutrition and reduced immune function, especially during dry seasons when nutrition is already limited. Climate change may exacerbate disease challenges by altering the distribution and abundance of disease vectors like ticks and midges. Additionally, contact with domestic horses and donkeys increases the risk of disease transmission, particularly in areas where wildlife and livestock overlap. This interface between wild and domestic equids represents a significant conservation concern.

Drought and Resource Competition

Drought events, which are becoming more frequent and severe across much of Africa due to climate change, present a critical threat to zebra populations. Unlike some African mammals that can survive on very low-quality vegetation, zebras require relatively high-quality grasses to meet their nutritional needs. During droughts, not only does the quantity of available forage decrease, but the nutritional quality declines as well. This nutritional stress leaves zebras vulnerable to starvation, reduced reproductive success, and increased susceptibility to diseases and predation.

Competition for dwindling resources during drought periods intensifies both within zebra populations and between zebras and other grazers, including domestic livestock. Studies in Kenya have documented significant zebra mortality during severe drought years, with the strongest impact on the very young and old individuals. Some zebra populations undertake longer migrations or range shifts in response to drought, but these movements may be increasingly restricted by habitat fragmentation and human development. Conservation strategies that protect critical dry-season grazing areas and maintain access to permanent water sources are essential for reducing drought-related mortality in zebra populations.

Conservation Status of Different Zebra Species

The conservation status varies significantly among the three zebra species. Plains zebras (Equus quagga), the most abundant and widespread species, are currently classified as Near Threatened on the IUCN Red List. While their overall population exceeds 500,000 individuals across eastern and southern Africa, certain subspecies face greater threats. The Quagga subspecies (E. q. quagga) was hunted to extinction in the late 19th century, while the Cape Mountain zebra subspecies has recovered from near extinction to approximately 5,000 individuals today thanks to dedicated conservation efforts.

Mountain zebras (Equus zebra) are listed as Vulnerable, with two recognized subspecies: the Cape Mountain zebra and the Hartmann’s Mountain zebra. Their combined population numbers approximately 35,000 individuals, primarily in South Africa and Namibia. Most concerning is the status of Grevy’s zebra (Equus grevyi), classified as Endangered with fewer than 2,000 individuals remaining, primarily in Kenya with a small population in Ethiopia. Their population has declined by over 80% since the 1970s due to hunting, habitat loss, and competition with livestock. Targeted conservation efforts, including community-based protection programs and strict anti-poaching measures, are critical for the survival of this distinctive species.

Protected Areas and Their Importance

Protected areas form the cornerstone of zebra conservation across Africa. National parks, game reserves, and conservation areas provide crucial safe havens where zebras can live with reduced human pressures. Major protected areas supporting significant zebra populations include the Serengeti-Mara ecosystem (Tanzania/Kenya), Kruger National Park (South Africa), Etosha National Park (Namibia), and Hwange National Park (Zimbabwe). These areas not only shelter zebras from direct threats like poaching and habitat conversion but also maintain the ecological processes and predator-prey relationships that shape natural zebra population dynamics.

However, even within protected areas, zebras face challenges. Many reserves are too small to accommodate the full range of seasonal movements that zebras evolved to undertake, particularly in regions with distinct wet and dry seasons. Climate change impacts can affect protected areas just as they do unprotected landscapes. Additionally, growing tourism pressure in some popular parks can disrupt zebra behavior and habitat use. Conservation biologists increasingly recognize that protected areas alone are insufficient for long-term zebra conservation; they must be complemented by wildlife-friendly land management practices in surrounding areas and connectivity between protected zones to allow for natural movements and genetic exchange.

Conservation Initiatives and Success Stories

Despite the numerous threats facing wild zebras, conservation initiatives across Africa have achieved important successes. The recovery of the Cape Mountain zebra represents one of Africa’s most remarkable conservation turnarounds. By the early 20th century, hunting had reduced their population to fewer than 50 individuals. Through strict protection, habitat preservation, and carefully managed reintroductions, their numbers have increased to approximately 5,000 today—a powerful example of how dedicated conservation efforts can reverse population declines even from the brink of extinction.

Community-based conservation programs have shown particular promise for zebra protection. In northern Kenya, the Grevy’s Zebra Trust works directly with local pastoralist communities, employing “Grevy’s Zebra Warriors” from these communities to monitor zebra populations and protect critical habitat. This approach has helped stabilize Grevy’s zebra populations in some areas while providing economic benefits to communities through conservation-related employment. Similar community-centered approaches are being implemented for Plains and Mountain zebras across their ranges. These initiatives recognize that long-term conservation success depends on the support and involvement of the people who share the landscape with zebras and other wildlife.

The future of wild zebras depends on addressing multiple interconnected threats through coordinated conservation action. Climate change adaptation must be central to future conservation planning, with increased protection of drought refuges and migration corridors that allow zebras to respond to shifting resource availability. Reducing human-wildlife conflict requires innovative approaches that balance the needs of growing human populations with those of zebras and other wildlife. This may include improved livestock management practices, sustainable agriculture that minimizes encroachment into zebra habitat, and economic incentives for conservation on private and community lands.

Advanced technologies are increasingly aiding zebra conservation efforts. Satellite tracking collars provide detailed information about zebra movements and habitat use, helping identify critical areas for protection. Genetic studies offer insights into population connectivity and diversity, guiding management decisions to maintain genetic health. Conservation drones and remote sensing technologies enable more efficient monitoring of zebra populations and their habitats, especially in remote or inaccessible areas. These tools, combined with traditional ecological knowledge and community involvement, offer hope that Africa’s iconic zebras will continue to roam the continent’s grasslands and savannas for generations to come. The story of zebra conservation illustrates both the challenges of wildlife protection in a rapidly changing world and the potential for success when science, policy, and community engagement align toward a common conservation goal.

- The Lifespan of a Wild Zebra—and What Threatens It - August 13, 2025

- 10 Times US Military Dogs Performed Acts of Unbelievable Bravery - August 13, 2025

- These Plants Eat Insects, But One Species Has Been Caught Eating Something Even Bigger - August 13, 2025