Every year, billions of birds embark on extraordinary journeys across continents and oceans, navigating through diverse landscapes and weather conditions with remarkable precision. This phenomenon, known as migration, represents one of nature’s most spectacular events and has fascinated scientists and bird enthusiasts for centuries. Bird migration isn’t merely a magnificent display of natural instinct; it’s a complex behavior shaped by evolution, environmental cues, and physiological adaptations. Understanding the science behind these incredible journeys can help us appreciate the challenges migratory birds face in an increasingly changing world and inspire us to take action to protect these remarkable travelers. In this article, we’ll explore the fascinating science of bird migration and discover practical ways you can contribute to conservation efforts that support these winged wanderers.

The Evolutionary Purpose of Migration

Bird migration evolved as a survival strategy that allows species to take advantage of seasonally abundant resources while avoiding harsh conditions. During spring migration, birds travel to northern breeding grounds where longer days and plentiful insects provide optimal conditions for raising young. As winter approaches and food becomes scarce, they journey south to regions with more favorable climates and food availability. This adaptive behavior developed over thousands of years as birds that successfully migrated passed these beneficial traits to their offspring. Migration represents a remarkable evolutionary trade-off: the considerable energy expenditure and risks of long-distance travel are balanced against the reproductive and survival advantages gained from accessing seasonally abundant resources. Not all birds migrate, but for approximately 19% of known bird species (around 1,800 species), this strategy has proven successful for their survival, demonstrating the diverse evolutionary paths that birds have taken to thrive in changing environments.

Remarkable Migration Champions

Some bird species have developed truly astonishing migration capabilities that push the boundaries of animal endurance. The Arctic Tern holds the record for the longest migration, traveling approximately 44,000 miles annually between its Arctic breeding grounds and Antarctic wintering areas—equivalent to circling Earth nearly twice. The Bar-tailed Godwit can fly over 7,000 miles nonstop across the Pacific Ocean from Alaska to New Zealand, sustaining flight for up to nine days without food, water, or rest. Ruby-throated Hummingbirds, weighing just 3-4 grams, cross the 500-mile expanse of the Gulf of Mexico in a single journey. Blackpoll Warblers, small songbirds weighing less than an ounce, make a nonstop 1,500-mile autumn flight over the Atlantic Ocean from New England to South America. These incredible feats highlight the remarkable physiological adaptations these birds have evolved, including specialized fat storage capabilities, efficient oxygen utilization, and the ability to sleep with one hemisphere of their brain at a time during flight—all enabling them to accomplish these extraordinary journeys year after year.

The Incredible Navigation Toolkit

Birds possess a sophisticated array of navigation methods that scientists are still working to fully understand. Many migratory birds can detect Earth’s magnetic field through specialized cells containing magnetite or light-sensitive proteins in their eyes, creating a biological compass that provides directional information. The sun serves as another crucial navigational tool, with birds using its position along with an internal circadian clock to determine direction. At night, star patterns guide nocturnal migrants, with studies showing that birds can learn celestial navigation by observing the night sky. Familiar landmarks like mountains, rivers, and coastlines help birds refine their routes during migration, particularly as they approach their destinations. Some species even navigate using their sense of smell, detecting oceanic or vegetation odors that indicate proximity to their destination. Perhaps most remarkably, birds appear to have an internal map sense that combines these various inputs with inherited genetic information about migration routes, creating a multi-layered navigation system that surpasses the most sophisticated human technology in its reliability and adaptability.

Physiological Transformations Before Migration

Before undertaking their arduous journeys, migratory birds undergo remarkable physiological changes that prepare their bodies for the extreme endurance challenge ahead. The most visible change is hyperphagia—a dramatic increase in feeding behavior that allows birds to accumulate substantial fat reserves, sometimes doubling their body weight in just a few weeks. This stored fat serves as the primary fuel for long migratory flights. Beyond simple weight gain, birds experience changes in muscle composition, with flight muscles developing higher densities of mitochondria and energy-producing enzymes to enhance aerobic capacity. Many species undergo selective atrophy of non-essential organs to reduce weight; the digestive tract may temporarily shrink by up to 40%, while the reproductive organs become dormant outside of breeding season. The respiratory and cardiovascular systems also adapt, with increases in lung capacity, heart size, and red blood cell count to support the extraordinary oxygen demands of sustained flight. These comprehensive physiological transformations, triggered by changing day length and controlled by complex hormonal changes, demonstrate the remarkable plasticity of avian biology and the evolutionary importance of migration for these species.

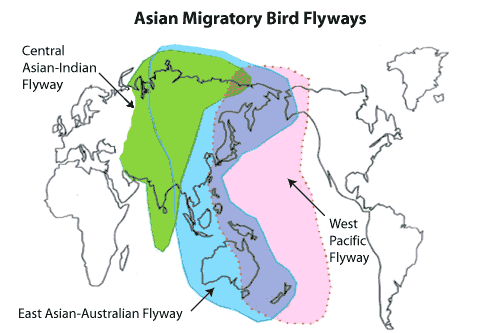

Flyways: The Highways of the Sky

Migratory birds don’t travel randomly across the landscape but instead follow established aerial corridors known as flyways—broad geographical paths that connect breeding and wintering grounds. Globally, there are eight major flyway systems that channel bird movements: the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific Flyways in the Americas; the East Atlantic, Black Sea/Mediterranean, East Asia/Australian, and Central Asian Flyways across the Eastern Hemisphere. These pathways have developed over thousands of years, shaped by geographical features like mountain ranges, coastlines, and river valleys that provide favorable navigation conditions and critical stopover sites. Flyways aren’t simply straight lines but complex networks that can vary by species, season, and weather conditions. They represent critical conservation units, as birds using these routes face similar challenges and depend on the same chain of habitats for successful migration. International conservation efforts increasingly focus on protecting entire flyway systems rather than isolated habitats, recognizing that migratory birds require connected landscapes spanning political boundaries. By understanding and protecting these aerial highways, conservationists aim to maintain the ecological connectivity essential for the billions of birds that traverse these ancient skyways each year.

The Crucial Role of Stopover Sites

Stopover sites—areas where birds pause during migration to rest and refuel—are as vital to successful migration as the breeding and wintering grounds themselves. These locations, which include wetlands, coastlines, forests, and grasslands, serve as critical refueling stations where birds can replenish energy reserves depleted by long flights. During stopovers, migrants may double their body mass through intensive feeding, with some species gaining up to 10% of their body weight daily. The time spent at these sites varies widely, from brief overnight stays to several weeks, depending on weather conditions, food availability, and the bird’s physical condition. Recent research using tracking technology has revealed that many birds show remarkable site fidelity, returning to the same stopover locations year after year, suggesting these areas have reliable resources that birds depend upon. Unfortunately, many traditional stopover habitats face threats from development, agricultural intensification, and climate change, creating potential bottlenecks in migration routes. The conservation of stopover sites presents unique challenges, as these areas may host massive numbers of birds for short periods while appearing relatively unimportant at other times of year. Effective protection of these crucial way stations requires recognition of their seasonal importance and targeted conservation efforts that maintain habitat quality during peak migration periods.

Timing Is Everything: Migration Triggers

The precise timing of bird migration relies on a complex interplay of internal and external factors that ensure birds arrive at their destinations when conditions are optimal. Photoperiod—the changing length of daylight—serves as the primary trigger, stimulating hormonal changes that initiate migratory restlessness (Zugunruhe) and the physiological preparations needed for long-distance travel. This internal clock is remarkably accurate, with captive birds showing migratory behaviors at the appropriate time even when kept under constant light conditions. While day length provides the base schedule, birds also respond to environmental cues to fine-tune their departure dates. Factors such as temperature trends, food availability, wind patterns, and barometric pressure influence when birds actually take flight. Different species vary in their dependence on these factors; long-distance migrants that cross ecological barriers like oceans tend to follow more rigid, photoperiod-driven schedules, while shorter-distance migrants show greater flexibility in response to local conditions. This timing mechanism faces growing challenges from climate change, which may create mismatches between traditional migration schedules and the peak availability of resources at breeding grounds. Recent research indicates that some species are adjusting their migration timing in response to warming temperatures, but scientists worry that not all birds can adapt quickly enough to keep pace with rapidly changing conditions.

Threats to Migratory Birds

Migratory birds face a gauntlet of challenges throughout their annual journeys, with human activities amplifying these dangers. Habitat loss along migration routes creates critical gaps in the chain of resources birds need, with wetland drainage, deforestation, and coastal development destroying crucial stopover sites. Climate change represents a growing threat, altering the timing of seasonal food peaks and creating mismatches with traditional migration schedules. Roughly one billion birds die annually from collisions with buildings in the United States alone, with light pollution disorienting nocturnal migrants and drawing them toward dangerous urban areas. Energy infrastructure like wind turbines and power lines cause additional mortality, while communication towers and tall buildings can confuse birds, especially during poor weather conditions. Hunting pressure remains significant in some regions, particularly along Mediterranean flyways where millions of migratory birds are illegally killed each year. The cumulative impact of these threats is evident in population trends, with the 2022 State of the World’s Birds report indicating that 48% of bird species globally are declining, with migratory species suffering steeper declines than resident birds. These threats are particularly concerning because they affect birds throughout their annual cycle, requiring coordinated conservation efforts across international boundaries to address challenges that span continents.

Make Your Backyard Bird-Friendly

Transforming your yard into a bird-friendly haven creates valuable habitat for both migratory and resident birds. Start by planting native vegetation that provides natural food sources through fruits, seeds, and by attracting insects that birds feed on. Include a diversity of plant types and heights to create structural variety that offers shelter, nesting sites, and feeding opportunities for different species. Water features, from simple bird baths to small ponds, provide essential resources for drinking and bathing, especially important during migration when birds need to maintain optimal condition. Reduce or eliminate pesticide use, as these chemicals can harm birds directly and reduce insect populations that many species depend on for food. Create bird safety zones by applying decals or patterns to large windows to prevent collisions, keeping cats indoors or supervised, and positioning feeders either very close to windows (where birds can’t build up lethal momentum) or more than 30 feet away. For those in migration corridors, consider participating in “lights out” programs during peak migration seasons by turning off unnecessary outdoor lighting at night, which helps prevent the disorientation of nocturnal migrants. These simple backyard modifications collectively create a network of safe havens that can significantly support bird populations throughout the year.

Citizen Science: Become a Migration Monitor

Citizen science projects offer a meaningful way for bird enthusiasts to contribute to migration research while enhancing their own knowledge and connection to birds. Programs like eBird, managed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, enable anyone to record bird observations that help scientists track migration patterns, population trends, and habitat use across continental scales. With millions of observations submitted annually, these collective efforts provide data at a scale impossible for professional scientists to gather alone. For those interested in a more structured approach, participating in organized bird counts like the Christmas Bird Count or Global Big Day connects you with worldwide bird monitoring efforts that have documented bird population changes for decades. More specialized programs focus on particular aspects of migration; Project FeederWatch monitors winter bird populations, while FrogWatch and the Monarch Larva Monitoring Project track other migratory species that share habitats with birds. Window collision monitoring projects in urban areas help document bird strikes and identify problem areas for mitigation. Many of these programs require no specialized expertise to start, offering training resources and community support for beginners. Beyond generating valuable scientific data, participation in these citizen science efforts creates a deeper awareness of local bird movements and seasonal patterns, fostering a stronger connection to the natural rhythms of bird migration in your area.

Conservation Through Sustainable Choices

Our everyday decisions can collectively reduce threats to migratory birds across their range. Choosing shade-grown coffee and cacao supports farming practices that maintain forest canopy in tropical regions where many North American migrants spend their winters, preserving crucial habitat while providing fair income for farmers. Reducing single-use plastics helps prevent pollution that can entangle or be ingested by birds, especially in marine environments where seabirds are particularly vulnerable. Energy conservation reduces carbon emissions that drive climate change while also decreasing demand for energy infrastructure like power lines and wind farms that can threaten migrating birds. Supporting sustainable forestry through certified wood products helps ensure that timber harvesting maintains habitat features important for forest-dwelling migrants. Making bird-friendly dietary choices, such as selecting sustainably harvested seafood, reduces pressure on marine ecosystems where many seabirds feed. For those who hunt, using non-toxic alternatives to lead ammunition prevents poisoning of birds that scavenge gut piles or consume wounded prey. These individual choices may seem small, but when adopted widely, they create significant positive impacts across the landscapes birds traverse during migration. By aligning our consumption patterns with bird conservation goals, we extend our positive influence far beyond our immediate surroundings to support migratory birds throughout their annual cycles.

Advocacy for Bird-Friendly Policies

Effective bird conservation requires supportive policies at local, national, and international levels, making advocacy an essential complement to individual actions. Start locally by engaging with municipal decisions about urban development, promoting bird-friendly building designs, dark sky lighting ordinances, and the preservation of urban green spaces that serve as stopover habitat. Support land conservation initiatives like local bond measures for open space preservation or the expansion of protected areas that safeguard critical habitats. At the national level, advocacy for strong environmental legislation like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in the United States provides legal protection for birds across their range. International agreements, including the Convention on Migratory Species and the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands, establish frameworks for cross-border cooperation essential for species that traverse political boundaries. Climate policy advocacy indirectly supports bird conservation by addressing one of the most pervasive threats to migratory species. Effective advocacy doesn’t require specialized expertise—writing to elected officials, signing petitions, participating in public comments on proposed regulations, and supporting conservation organizations that engage in policy work all contribute to creating a political environment more favorable to bird conservation. By raising your voice for birds, you help ensure that their needs are considered in the decisions that shape our shared landscapes.

The marvel of bird migration represents one of nature’s greatest wonders—a testament to the extraordinary adaptability and resilience of birds in the face of environmental challenges. As we’ve explored, these epic journeys depend on complex navigational abilities, remarkable physiological adaptations, and a chain of suitable habitats spanning continents. The threats facing migratory birds today are significant, but so too is our growing understanding of their needs and our capacity to help. By creating bird-friendly spaces, participating in citizen science, making sustainable consumer choices, and advocating for bird-friendly policies, each of us can contribute to a world where the ancient phenomenon of bird migration continues to connect distant ecosystems and inspire human wonder. The future of migratory birds depends not just on the actions of scientists and conservationists but on millions of individual choices made by people who recognize the value of these feathered travelers and the ecological connections they represent across our planet.

- The Fish That Builds Nests - August 23, 2025

- The Insect That Ices Itself - August 23, 2025

- 15 Weirdest Things Fish Can Do - August 23, 2025