In the animal kingdom, intelligence is often associated with mammals that possess large, complex brains—particularly primates like chimpanzees and household pets like dogs. These animals demonstrate problem-solving abilities, emotional intelligence, and even rudimentary tool use. However, recent research has uncovered surprising cognitive abilities in a creature that lacks the brain structure we typically associate with intelligence: the common octopus. Despite having a radically different nervous system than vertebrates, octopuses display problem-solving skills that sometimes surpass those of chimps and dogs, challenging our understanding of animal cognition and the evolution of intelligence.

The Remarkable Octopus Brain

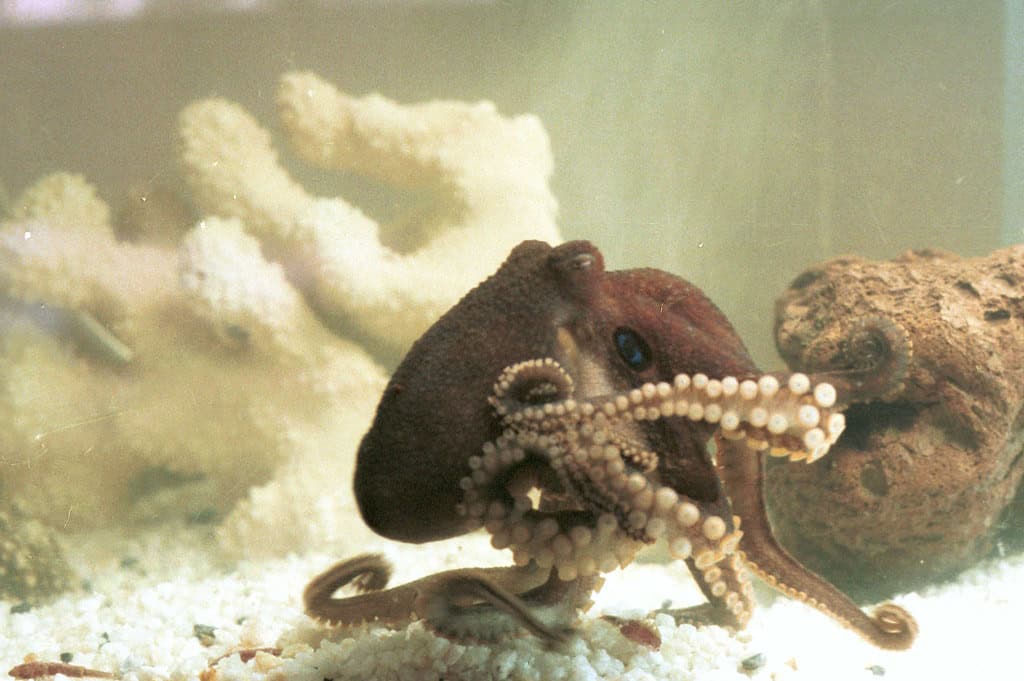

Unlike the centralized brains of mammals, the octopus possesses a distributed nervous system with approximately 500 million neurons—similar to the number found in dogs. However, what makes their neural architecture revolutionary is that only about one-third of these neurons reside in the central brain. The remaining two-thirds are distributed throughout their eight arms, creating a decentralized intelligence that operates fundamentally differently from our own. Each arm contains about 40 million neurons and can function somewhat independently, allowing the octopus to delegate certain tasks to its limbs without central brain oversight.

This distributed intelligence enables octopuses to solve complex problems using different neural strategies than mammals. Their brain evolved independently from vertebrates, with the last common ancestor between octopuses and humans living over 500 million years ago. This makes octopus intelligence one of the most fascinating examples of convergent evolution—where similar traits develop independently in unrelated lineages—in the animal kingdom.

Problem-Solving Capabilities

Octopuses have repeatedly demonstrated exceptional problem-solving abilities in laboratory settings. They can navigate mazes, unscrew jar lids to access food, and even use tools—behaviors once thought exclusive to primates and some birds. In one famous experiment, octopuses were presented with closed jars containing food; they quickly learned to unscrew the lids, requiring both memory and dexterity. Another test showed octopuses could solve puzzles requiring multiple sequential steps, demonstrating planning capabilities comparable to those of chimpanzees.

Perhaps most impressively, octopuses show individual problem-solving strategies. When faced with the same challenge, different octopuses may develop entirely different solutions, suggesting not just intelligence but creativity. Some scientists have observed octopuses using coconut shells as portable shelters and manipulating objects in their environment to create tools—a level of innovation that rivals and sometimes exceeds what we observe in chimps and certainly surpasses the capabilities of most dogs.

Memory and Learning

Despite having a lifespan of only 1-2 years, octopuses display remarkable memory capabilities. They can remember solutions to problems they’ve encountered before and apply this knowledge to new situations. Research shows they can recognize individual humans, even when those people wear the same uniform, and will react differently to people who have treated them well versus those who have annoyed them. This ability to recognize and remember individuals is comparable to that of dogs and suggests a sophisticated memory system.

Octopuses also demonstrate both short-term and long-term memory. They can learn through observation and retain information for extended periods—up to several months in some studies. This capacity for learning is particularly impressive given their short lifespan, suggesting a neural efficiency that allows rapid acquisition of complex behaviors, sometimes outpacing the learning curves observed in mammalian species like dogs.

The Puzzle of Octopus Play

Play behavior, once considered exclusive to mammals and some birds, has been documented in octopuses. They have been observed manipulating objects with no apparent purpose other than entertainment—pushing objects around their tanks, shooting jets of water at floating items, and even engaging in what appears to be games. At the Seattle Aquarium, octopuses were documented repeatedly releasing plastic toys into the water current, then catching them—an activity with no survival benefit that strongly resembles play.

This playful behavior is significant because play is often associated with higher cognitive functions and is considered a hallmark of intelligence in other species. The fact that octopuses engage in play despite having evolved along a completely different evolutionary path suggests that play may be a fundamental aspect of intelligence regardless of brain structure. This convergent evolution of play behavior places octopuses in the rare company of intelligent mammals and birds, despite their radically different neural architecture.

Tool Use Without Opposable Thumbs

Perhaps one of the most surprising aspects of octopus intelligence is their ability to use tools despite lacking the skeletal structure and opposable thumbs that facilitate tool use in primates. Octopuses have been observed collecting coconut shells, carrying them around, and then assembling them into shelters when needed. They’ve also been seen using rocks to wedge open clam shells and wielding sticks to poke at interesting objects. Some species even use shells and other debris as armor against predators.

This sophisticated tool use is particularly remarkable because it evolved independently from tool use in mammals. While chimpanzees use tools primarily with their hands, octopuses use their entire arms, which are covered with suckers capable of fine manipulation and chemical sensing. This represents a completely different evolutionary solution to the challenge of manipulating the environment—one that works remarkably well despite developing along a different path than the primate hand.

Social Intelligence Without Social Lives

Unlike chimpanzees and dogs, which evolved in highly social environments that selected for social intelligence, octopuses are largely solitary creatures. This makes their cognitive abilities even more remarkable, as they developed high intelligence without the social pressures thought to drive brain evolution in primates and canines. While the “social brain hypothesis” suggests that the complex cognitive demands of group living drove primate intelligence, octopuses prove that high intelligence can evolve in the absence of complex social structures.

Despite their solitary nature, when octopuses do interact with each other or with humans, they display sophisticated social behaviors. They can learn from watching other octopuses solve problems, recognize individual humans, and adjust their behavior based on previous interactions. This suggests a form of social intelligence that developed for different evolutionary reasons than in social mammals, perhaps related to predator avoidance or complex hunting strategies rather than group cooperation.

Escape Artists: Evidence of Planning

Octopuses are notorious escape artists, capable of squeezing through openings as small as their beaks—the only hard part of their bodies. Their escape behaviors often display remarkable planning and foresight. Aquarium staff worldwide have documented octopuses waiting until humans leave before executing escape plans, unscrewing tank lids from the inside, navigating complex pipe systems, and even traveling across dry floors to reach other tanks. One famous octopus at the New Zealand National Aquarium, named Inky, escaped through a small gap in his tank, traveled across the floor, and disappeared down a 164-foot drainpipe leading to the ocean.

These escape behaviors demonstrate not just problem-solving but the ability to plan and execute multi-step actions toward a goal—a cognitive ability once thought limited to animals with prefrontal cortices like primates. The planning involved in these escapes sometimes exceeds what we observe in dogs and rivals the planning capabilities of chimpanzees, despite the octopus’s radically different brain structure. This suggests that planning and foresight may be fundamental aspects of intelligence that can evolve through different neural pathways.

Sensory Intelligence: A Different Kind of Smart

The octopus’s intelligence is intimately connected to its extraordinary sensory capabilities. Their arms contain chemoreceptors that allow them to “taste” by touch, effectively giving them eight “tongues” that can independently explore and analyze their environment. Their visual system, with camera-like eyes similar to our own (another example of convergent evolution), provides high-resolution vision. They can also detect polarized light—an ability humans lack—allowing them to communicate through skin pattern changes invisible to many predators.

This rich sensory world creates a form of intelligence quite different from our own. While human intelligence relies heavily on abstract thinking facilitated by language, octopus intelligence appears more deeply embedded in direct sensory experience. Their problem-solving often involves coordinating multiple senses and body parts simultaneously in ways that would be challenging even for primates. This sensory-motor intelligence represents a different but equally sophisticated form of cognition that has evolved to meet the challenges of an octopus’s unique ecological niche.

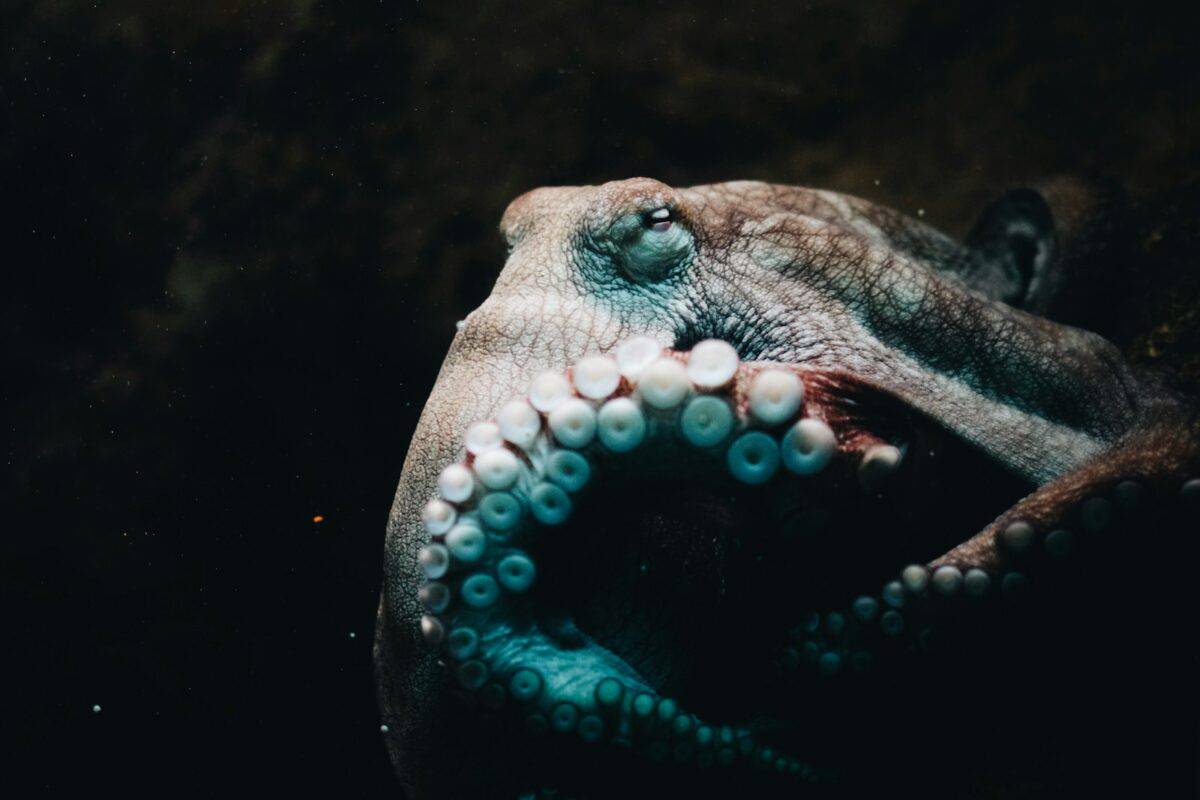

Camouflage: The Thinking Skin

One of the most remarkable displays of octopus intelligence is their unparalleled camouflage ability. Octopuses can instantly change their skin color, pattern, and texture to match their surroundings through a complex system of chromatophores, leucophores, and iridophores controlled by their nervous system. This is not a simple reflex but requires sophisticated visual processing, pattern recognition, and decision-making about which camouflage strategy to employ. Some octopuses can even mimic other marine creatures, changing not just their appearance but their movement patterns to resemble dangerous sea snakes or harmless floating algae.

What makes this ability particularly astounding is that octopuses are colorblind, yet they can match the colors of their environment perfectly. Scientists believe they may be able to detect colors through their skin, effectively “seeing” without using their eyes. The neural processing required for this rapid adaptive camouflage exceeds the capabilities of most vertebrates and represents a form of embodied intelligence where the skin itself becomes an extension of the nervous system. This distributed sensory-motor intelligence allows octopuses to solve the complex problem of remaining hidden from predators in ways no dog or even chimpanzee could match.

Evolutionary Pressures: Why Intelligence Evolved

The question of why octopuses evolved such sophisticated intelligence without the social pressures thought to drive cognitive development in primates remains fascinating to scientists. Several theories exist, with the most compelling relating to their unique ecological niche. As soft-bodied creatures in predator-rich environments, octopuses faced intense selection pressure for problem-solving and adaptive behavior. Their lack of physical protection (like shells) meant they needed to rely on intelligence for survival—finding creative hiding places, manipulating objects for protection, and outwitting predators.

Additionally, octopuses are active predators themselves, hunting prey that often has its own defensive adaptations. This evolutionary arms race likely selected for increasing cognitive capabilities to outsmart both predators and prey. The short lifespan of octopuses (generally 1-2 years) also means they must learn quickly without the benefit of extended parental care that mammals receive, potentially selecting for rapid learning and innate problem-solving abilities. This confluence of evolutionary pressures created an intelligence that evolved independently from but rivals or exceeds that of many mammals, including dogs and sometimes even chimpanzees.

The Challenge to Human Exceptionalism

The remarkable intelligence of octopuses challenges long-held assumptions about the relationship between brain structure and cognition. For centuries, humans have placed ourselves at the pinnacle of an intelligence hierarchy, with other primates, mammals, and vertebrates following in descending order. The discovery of high intelligence in an invertebrate with a radically different nervous system forces us to reconsider this linear view of cognitive evolution and suggests that intelligence can take multiple forms, evolving through different pathways to meet similar challenges.

Octopus intelligence also challenges our understanding of the biological requirements for complex cognition. If a creature so evolutionarily distant from humans—with such a different brain structure and such a short lifespan—can develop problem-solving abilities that rival or exceed those of chimps and dogs in certain domains, then intelligence may be more fundamental to life than we previously thought. This realization has profound implications not just for our understanding of animal cognition but for how we might recognize intelligence in truly alien life forms, should we ever encounter them.

Rethinking Intelligence in the Animal Kingdom

The cognitive abilities of octopuses force us to broaden our definition of intelligence beyond mammal-centric models. Their problem-solving skills, memory, learning capacity, and adaptive behaviors represent a form of intelligence that evolved independently from our own yet achieves similar functional outcomes. This convergent evolution of intelligence suggests that certain cognitive capacities may be fundamental solutions to survival challenges, regardless of neural architecture or evolutionary history.

As we continue to study these remarkable creatures, we’re learning that intelligence in the animal kingdom is not a single ladder with humans at the top, but rather a complex branching tree with multiple forms of intelligence evolving to meet specific ecological challenges. The octopus—with its distributed brain, problem-solving capabilities that sometimes exceed those of dogs and chimps, and its radically different evolutionary history—stands as perhaps the most profound example of how intelligence can take unexpected forms. Their unique cognitive abilities remind us that in the vast diversity of life on Earth, intelligence manifests in ways we are only beginning to understand, challenging our assumptions and expanding our appreciation for the many paths evolution can take toward complex cognition.

- This Bird Sets Forests on Fire - August 17, 2025

- Orcas Have Regional Accents - August 17, 2025

- The Largest Group Migration in the Animal World - August 17, 2025