When most people think of monkeys, they often picture these intelligent primates hanging from trees, gleefully munching on bananas. While this iconic image isn’t entirely wrong, it vastly oversimplifies the diverse and complex dietary habits of wild monkeys. In reality, monkeys across different species and habitats consume an impressively varied diet that adapts to their environment, seasonal availability, and nutritional needs. From fruits and insects to flowers and even small vertebrates, the monkey menu extends far beyond the yellow curved fruit that’s become their stereotypical meal in popular culture.

The Banana Misconception

Let’s address the banana in the room first. While wild monkeys do eat bananas when available, the commercial bananas we’re familiar with aren’t native to many monkey habitats. Modern cultivated bananas are actually a human-developed hybrid, quite different from wild bananas that monkeys might encounter naturally. In their natural environments, most monkey species only occasionally come across wild bananas, which contain large seeds and less pulp than their grocery store counterparts.

The association between monkeys and bananas largely stems from captivity observations and popular media representations. Captive monkeys are often fed bananas because they’re inexpensive, readily available, and monkeys indeed enjoy their sweet taste. However, zoo nutritionists now recognize that a banana-heavy diet is actually unhealthy for monkeys, as cultivated bananas contain much more sugar and less fiber than the foods these animals would naturally consume in the wild.

Frugivores: The Fruit Specialists

Many monkey species are primarily frugivores, meaning fruits make up the largest portion of their diet. Spider monkeys, howler monkeys, and capuchins in the Americas, along with many Old World monkeys like macaques and mangabeys, derive 60-90% of their nutrition from fruits. These monkey species have evolved specialized digestive systems to process the sugars, fibers, and other nutrients found in various fruits.

Unlike humans who might focus on the sweetest, ripest fruits, wild monkeys often consume fruits at various stages of ripeness. They eat everything from young, unripe fruits (which contain more complex carbohydrates and less sugar) to fully ripened and even overripe fruits that have begun fermentation. This variety provides different nutritional profiles and helps monkeys maintain a balanced diet throughout seasonal changes when certain fruits may become more or less available.

Leafy Greens and Plant Matter

Leaves, shoots, and other plant matter constitute a significant portion of many wild monkeys’ diets. Folivory (leaf-eating) is particularly important for species like howler monkeys, colobus monkeys, and langurs. These species have evolved specialized stomachs similar to those of ruminants, with compartmentalized chambers hosting beneficial microbes that help break down cellulose in leaves that would otherwise be indigestible.

Even primarily fruit-eating monkeys supplement their diets with leaves, especially when fruits are scarce. Young leaves are typically preferred over mature ones because they contain more protein and fewer toxins and defensive compounds. Some monkey species have even developed detoxification strategies to handle certain levels of plant toxins, allowing them to access food sources that other animals cannot safely consume. This ability gives them a competitive edge in forest ecosystems.

Protein Sources: Insects and Small Animals

Contrary to the herbivore image many people have of monkeys, most species actively seek out animal protein. Insects form a crucial part of many monkey diets, providing essential amino acids, fats, and micronutrients that can be harder to obtain from plant sources alone. Capuchin monkeys, for instance, are skilled insect hunters who will peel back tree bark or probe into crevices to extract beetles, ants, termites, and caterpillars.

Some monkey species take their carnivorous tendencies further. Baboons and macaques occasionally hunt and consume small vertebrates including birds, lizards, and even other mammals like young antelope or hares. This predatory behavior is more common during dry seasons when plant foods become scarce. The consumption of animal protein is particularly important for pregnant females and growing juveniles, who have higher protein requirements for development.

The Importance of Flowers and Nectar

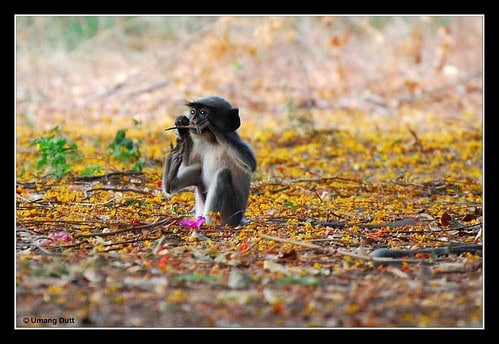

Flowers and nectar represent an often-overlooked component of wild monkey diets. These food sources are rich in sugars, proteins, and various micronutrients. During flowering seasons, many monkey species will dedicate significant foraging time to consuming flowers or drinking nectar. This behavior not only provides nutritional benefits but also plays an ecological role, as monkeys often serve as pollinators for certain plant species.

In some tropical forests, flowering events can be sporadic but massive, with entire canopies blooming simultaneously. During these events, monkeys may temporarily shift their dietary focus to take advantage of this abundant but ephemeral food source. Some smaller monkey species like marmosets and tamarins have evolved specialized dentition that allows them to gnaw holes in tree bark to stimulate the flow of gum and sap, which provides carbohydrates and minerals, especially during periods when other food sources are scarce.

Seeds, Nuts, and Underground Foods

Many monkey species consume seeds and nuts that provide concentrated sources of fats, proteins, and minerals. Species like the bearded saki and uakari have evolved powerful jaws and specialized teeth that can crack open hard nuts and seed pods that other animals cannot access. This adaptation allows them to exploit food resources with limited competition from other forest dwellers. Some monkeys will even consume unripe seeds from fruits, which often contain different nutritional compounds than the mature fruit pulp.

Underground plant parts such as roots, tubers, and corms also feature in some monkey diets, particularly during dry seasons when above-ground vegetation becomes limited. Baboons and macaques are known to dig for these underground resources, using their strong hands and problem-solving abilities to access these hidden food sources. These underground plant parts provide starches and carbohydrates that help monkeys maintain their energy levels when preferred foods are unavailable.

Seasonal Dietary Shifts

Wild monkeys display remarkable dietary flexibility in response to seasonal changes in food availability. During fruit-abundant seasons, frugivorous species may obtain up to 90% of their calories from fruits. However, when fruits become scarce during dry seasons or winter months, these same species will shift to alternative foods like leaves, flowers, bark, and insects. This dietary plasticity is crucial for survival in environments where food availability fluctuates dramatically throughout the year.

Research tracking monkey feeding patterns has revealed that some species migrate seasonally to follow food availability, traveling considerable distances to reach areas where particular trees are fruiting or flowering. Other species have adapted to remain in the same territory year-round by developing more diverse feeding strategies. These adaptations highlight the ecological intelligence of wild monkeys and their intimate knowledge of their habitat’s food resources and phenological cycles.

Regional Diet Variations

Monkey diets vary dramatically across different geographical regions and habitats. Mountain-dwelling Japanese macaques in colder climates have very different diets from their tropical cousins in Southeast Asia. The former may rely heavily on bark and buds during winter months when fruits are unavailable, while the latter have year-round access to diverse tropical fruits. Similarly, rainforest monkeys typically have access to more fruit species than monkeys living in drier woodland savannas, who may consume more seeds, roots, and insects.

Even closely related monkey species occupying different habitats will develop distinct dietary preferences and specializations. For example, among macaque species, the crab-eating macaque has evolved techniques to forage in mangrove swamps for crustaceans, while the Barbary macaque of North Africa’s mountains has adapted to a diet heavy in cedar nuts and oak acorns. These regional variations demonstrate how monkey diets are shaped by both evolutionary history and ecological context.

Social Learning and Food Processing

Wild monkeys don’t just eat whatever they find—they learn what to eat, when to eat it, and how to process it through social learning and cultural transmission. Juvenile monkeys observe adults in their group and gradually acquire knowledge about which foods are safe and nutritious, which require special processing techniques, and which should be avoided. This knowledge is passed down through generations, creating distinct feeding traditions within different monkey populations even of the same species.

Many monkey species employ sophisticated food processing techniques that enhance nutritional value or reduce toxicity. Capuchin monkeys, known for their exceptional intelligence, use stones as tools to crack open nuts and seeds. Japanese macaques wash sweet potatoes and wheat in water, removing dirt and salt. Some monkey species rub toxic leaves with other plant materials or soil before consumption, a behavior that helps neutralize defensive chemical compounds. These cultural feeding behaviors demonstrate that monkey diets are not just determined by instinct but are shaped by learned traditions.

Geophagy: Why Monkeys Eat Dirt

Many wild monkey species regularly engage in geophagy—the deliberate consumption of soil or clay. This behavior, once thought to be abnormal, is now recognized as an important dietary supplement. Soils, particularly certain clay types, contain minerals like calcium, magnesium, and potassium that may be limited in plant foods. Additionally, the binding properties of clay help monkeys detoxify certain plant compounds by adsorbing harmful substances in the digestive tract.

Geophagy is especially common among pregnant females, suggesting it may help address increased mineral demands or combat morning sickness-like symptoms. Researchers have observed that monkeys are highly selective about the soil they consume, often traveling to specific sites with particular soil compositions. Some monkey groups maintain traditional “salt lick” locations that are visited regularly across generations, highlighting the nutritional importance of these non-food substances in their overall dietary strategy.

Water Sources and Drinking Behavior

While not strictly part of their diet, water acquisition strategies are integral to understanding wild monkey nutrition. Many monkey species obtain most of their water directly from the foods they eat, particularly fruits, which can have high water content. However, most species will also drink from streams, ponds, tree hollows, or accumulated rainwater when needed. Some monkeys have developed fascinating adaptations for accessing water in challenging environments.

Baboons in arid environments can dig wells in dry riverbeds to access underground water. Certain macaque species have learned to dip their hands in water and lick the drops off their fur to hydrate. During dry seasons, some monkeys will chew bark or roots to extract moisture. These diverse strategies for obtaining water complement their feeding behaviors and further demonstrate the remarkable adaptability that has allowed monkeys to thrive in varied environments around the world.

Conservation Implications of Monkey Diets

Understanding the complex dietary needs of wild monkeys has critical implications for conservation efforts. As deforestation and habitat fragmentation continue to threaten monkey populations worldwide, many species face nutritional challenges when their diverse food sources disappear. Monkeys with specialized diets are particularly vulnerable—those that depend on specific fruit species or have complex nutritional requirements may struggle to adapt when their preferred foods become unavailable due to habitat loss or climate change.

Conservation strategies increasingly incorporate knowledge about monkey diets when designing protected areas or reforestation efforts. By ensuring that reserves contain the full range of plant species that local monkey populations depend on throughout the year, conservationists can better support viable wild populations. Additionally, research into wild monkey diets has influenced captive care practices in zoos and rehabilitation centers, where nutritionists now strive to provide varied diets that better replicate the diversity of foods these animals would naturally consume, moving far beyond the stereotype of monkeys subsisting on bananas.

Conclusion: Beyond the Banana

The diet of wild monkeys represents a fascinating example of dietary adaptability, ecological intelligence, and evolutionary specialization. From the fruit-heavy diets of spider monkeys swinging through Central American rainforests to the omnivorous feeding patterns of savanna baboons, these primates have developed remarkably diverse nutritional strategies that extend far beyond the simplified banana-eating stereotype. Their ability to extract nutrition from hundreds of plant and animal species, adapt to seasonal changes, and develop cultural feeding traditions underscores their impressive cognitive abilities and ecological importance.

Understanding the true complexity of wild monkey diets not only corrects popular misconceptions but also provides crucial insights for conservation and captive care. As we continue to learn more about the nutritional ecology of these remarkable animals, we gain a deeper appreciation for the intricate relationships between primates and their environments. The next time you see a cartoon monkey with a banana, remember that in the wild, that monkey would likely be enjoying a diverse buffet of fruits, leaves, insects, flowers, and even the occasional handful of nutritious soil—a diet as complex and adaptable as the fascinating animals themselves.

- How Penguins Take Turns at Sea and Nest to Raise Chicks - August 9, 2025

- Dolphin Brains Compare to Those of Apes and Humans - August 9, 2025

- 14 Cutting-Edge Biotech Innovations That Will Shape the Future - August 9, 2025