The Great Lakes, often celebrated for their pristine beauty and recreational opportunities, harbor more than meets the eye beneath their shimmering surfaces. These five interconnected lakes—Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario—contain 21% of the world’s fresh surface water and support diverse ecosystems teeming with life. But alongside native species and natural wonders lurk some surprising, concerning, and occasionally alarming residents that many visitors and even locals may not be aware of. From invasive species that have dramatically altered food webs to emerging contaminants of concern, ancient shipwrecks to mysterious underwater formations, the Great Lakes contain fascinating secrets in their depths. This exploration reveals what’s really lurking in these vast inland seas—some natural, some human-caused, and all part of the complex story of North America’s freshwater crown jewels.

Invasive Sea Lampreys: Vampires of the Lakes

Perhaps one of the most nightmarish creatures lurking in the Great Lakes is the sea lamprey (Petromyzon marinus), an ancient, eel-like parasitic fish that attaches to other fish with its suction-cup mouth lined with circular rows of razor-sharp teeth. Native to the Atlantic Ocean, these prehistoric creatures invaded the Great Lakes in the early 20th century after modifications to shipping canals removed natural barriers. Once attached to a host fish, the lamprey uses its rasping tongue to bore through scales and skin, then feeds on the fish’s blood and bodily fluids, often resulting in the host’s death.

The ecological impact of sea lampreys has been devastating. At their peak in the 1950s, they nearly destroyed the Great Lakes fishery, with lake trout catches in Lake Michigan plummeting from 6.7 million pounds annually to just 200,000 pounds. Today, an ongoing control program costing over $20 million annually helps manage their numbers through selective lampricides, barriers, and traps. Despite these efforts, an estimated 100 million pounds of fish still fall victim to sea lampreys each year across the Great Lakes basin, making them one of the most persistent and destructive invasive species in North American waters.

Zebra and Quagga Mussels: Tiny Invaders, Massive Impact

Arriving in ballast water of transoceanic ships in the late 1980s, zebra and quagga mussels have completely transformed the Great Lakes ecosystem. These small mollusks might seem inconsequential, but their numbers tell a different story—in some areas, population densities exceed 700,000 individuals per square meter. Their filtering capacity is equally staggering: the mussels in Lake Michigan can filter the entire volume of the lake in less than a week, removing vital phytoplankton that forms the base of the food web.

The ecological and economic consequences of these invasive mussels extend far beyond water clarity. They’ve contributed to the collapse of native mussel populations, facilitated harmful algal blooms by selectively filtering out beneficial algae, and caused billions in damage to infrastructure by clogging water intake pipes and encrusting boat hulls. Their spread has been nearly impossible to control once established, and they’ve now invaded waterways throughout the eastern United States. Perhaps most concerning is how they’ve fundamentally altered nutrient cycling in the lakes, creating what scientists call “the Great Lakes’ ecological regime shift”—a dramatic, potentially irreversible transformation of these freshwater ecosystems.

PFAS: The “Forever Chemicals” in Great Lakes Waters

Beneath the surface of the Great Lakes lurks an invisible threat—per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a group of over 9,000 synthetic chemicals used in everything from non-stick cookware to firefighting foam. These “forever chemicals” earned their nickname because they don’t break down naturally in the environment or the human body, potentially remaining for thousands of years. Recent monitoring has detected PFAS in all five Great Lakes, with concerning concentrations in fish, wildlife, and even drinking water sourced from the lakes.

The health implications of PFAS exposure are increasingly troubling. Scientific studies have linked these chemicals to kidney and testicular cancer, decreased fertility, developmental delays in children, reduced immune response, and increased cholesterol levels. The Great Lakes region has several PFAS hotspots, including areas near Marinette, Wisconsin, and Oscoda, Michigan, where industrial discharges and the use of firefighting foam at military bases have created plumes of contamination. While regulatory efforts are increasing, with some states establishing drinking water standards for certain PFAS compounds, removing these persistent chemicals from such vast bodies of water presents an unprecedented environmental challenge that will likely affect generations to come.

Microplastics: A Growing Invisible Threat

The Great Lakes have become a significant repository for microplastics—plastic particles less than 5mm in size that include manufactured microbeads from personal care products and fragments from the breakdown of larger plastic items. Research has revealed alarming concentrations, with Lake Michigan containing an estimated average of 17,000 microplastic pieces per square kilometer of surface water. These tiny fragments have been found throughout the water column, in lake sediments, and in the digestive systems of fish and aquatic birds.

What makes microplastics particularly concerning is their ability to absorb and concentrate toxic chemicals from the surrounding water, essentially acting as delivery vehicles for pollutants into the food web. Studies have detected microplastics in Great Lakes beer brewed with lake water, table salt harvested from the lakes, and tap water from municipalities drawing from these freshwater sources. While the U.S. banned microbeads in rinse-off personal care products in 2015, the vast majority of microplastics come from the breakdown of larger items, meaning the problem continues to grow as the estimated 22 million pounds of plastic entering the Great Lakes annually gradually fragments into smaller and smaller pieces that may remain in the ecosystem for centuries.

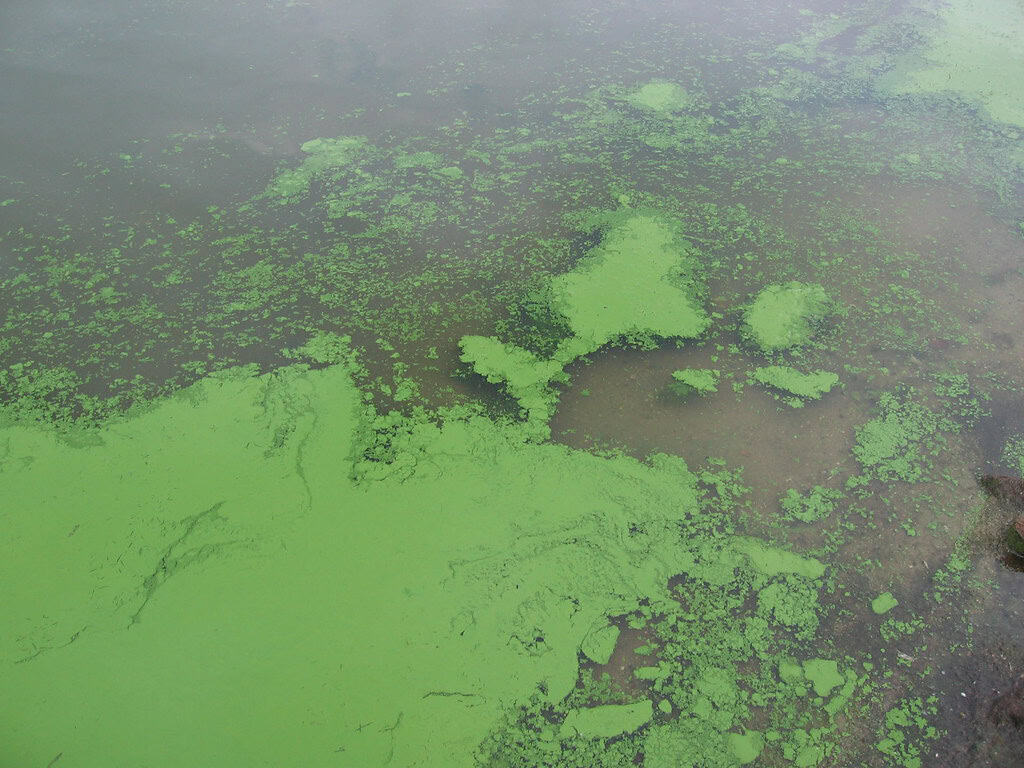

Harmful Algal Blooms: Toxic Green Monsters

Some of the most visible and dangerous phenomena lurking in the Great Lakes are harmful algal blooms (HABs)—explosive growths of cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) that can turn vast areas of water into toxic green soup. Lake Erie has become notorious for these blooms, with the 2014 event growing so large it was visible from space and contaminating Toledo, Ohio’s drinking water, leaving over 400,000 residents without safe tap water for three days. These blooms produce potent toxins including microcystin, which can cause liver damage, respiratory problems, and skin irritation in humans and has been responsible for pet deaths when dogs swim in or drink contaminated water.

The primary driver behind the resurgence of these harmful blooms is agricultural runoff rich in phosphorus and nitrogen, particularly from fertilized croplands and livestock operations in the western Lake Erie basin. Climate change exacerbates the problem, as warmer water temperatures and more intense rain events create ideal conditions for cyanobacteria growth while increasing nutrient runoff. Despite billions invested in water quality improvements since the Clean Water Act, harmful algal blooms have returned with increasing frequency and intensity since the 1990s, creating dead zones depleted of oxygen that threaten fish populations and rendering beaches unusable during summer months when recreation should be at its peak.

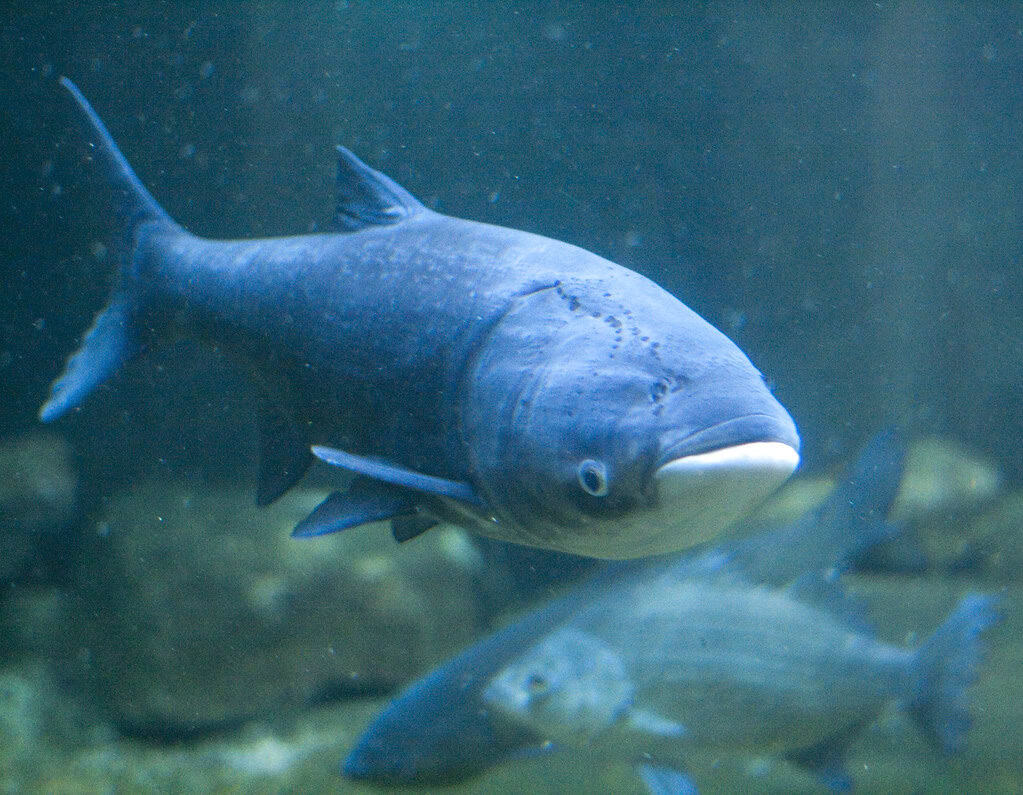

Asian Carp: The Invaders at the Gates

Hovering at the threshold of the Great Lakes is perhaps their most feared potential invader: Asian carp. This umbrella term encompasses several species including bighead, silver, grass, and black carp—large, voracious fish originally imported to the southern United States for aquaculture and wastewater treatment ponds in the 1970s. After escaping during floods, they’ve been steadily moving northward through the Mississippi River system. Silver carp, known for leaping several feet out of the water when startled by boat motors, have caused serious injuries to boaters, while bighead carp can grow to over 100 pounds and consume up to 40% of their body weight daily in plankton.

The potential ecological and economic impacts of an Asian carp invasion in the Great Lakes are staggering, with estimates suggesting they could decimate the region’s $7 billion fishing industry and $16 billion recreational boating economy. The primary defense has been a series of electric barriers in the Chicago Area Waterway System, but environmental DNA of Asian carp has already been detected past these barriers in waters connected to Lake Michigan. In 2021, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction on additional preventative measures at Brandon Road Lock and Dam in Illinois, but the $858 million project won’t be completed until at least 2025, leaving the Great Lakes vulnerable to what many biologists consider an ecological disaster waiting to happen.

Shipwrecks: Underwater Time Capsules and Environmental Hazards

The Great Lakes hold the world’s largest collection of freshwater shipwrecks, with an estimated 6,000 vessels lost throughout their history. These underwater time capsules provide fascinating glimpses into maritime history, from wooden schooners of the 1800s to massive steel freighters of the early 20th century. The cold, fresh water of the lakes creates ideal preservation conditions, with many wrecks remaining remarkably intact. Notable examples include the Edmund Fitzgerald in Lake Superior, which sank in 1975 with all 29 crew members lost, and the Cornelia B. Windiate in Lake Huron, which sits perfectly preserved in the cold depths since its disappearance with all hands in 1875.

While these shipwrecks serve as artificial reefs supporting aquatic life and attract thousands of recreational divers annually, they also present environmental concerns. Many older vessels contain hazardous materials including bunker fuel, lubricating oils, coal, and even unexploded ordnance from military vessels. The deterioration of these wrecks can release contaminants into the surrounding water, as demonstrated by the slow leak of oil from the Argo, a barge that sank in Lake Erie in 1937 and began leaking petroleum products in 2015. Efforts to identify and remediate the most hazardous wrecks are ongoing, balancing preservation of maritime heritage with protection of the lakes’ fragile ecosystems.

VHS: The Invisible Fish Killer

Viral hemorrhagic septicemia (VHS) represents an invisible but lethal threat lurking in Great Lakes waters. This pathogen, often called the “fish Ebola” by researchers, causes bleeding in fish tissues and has been responsible for massive die-offs affecting over 30 fish species in the Great Lakes. The virus first appeared in the lower Great Lakes in 2005, likely introduced through ballast water from oceangoing vessels, and has since spread throughout the basin. Infected fish develop hemorrhages that appear as red patches on their skin and internal organs, eventually leading to death from internal bleeding and organ failure.

The economic and ecological impacts of VHS have been substantial, affecting both commercial fishing operations and recreational angling. Species particularly vulnerable include muskellunge, freshwater drum, yellow perch, and round goby. While not harmful to humans, the virus has prompted restrictions on moving live fish between water bodies and required changes in hatchery operations to prevent spreading the pathogen. What makes VHS particularly concerning is its ability to survive in cold water for extended periods and to be transmitted through contaminated fishing equipment, allowing it to spread to inland lakes and rivers. Despite declining reports of major die-offs in recent years, the virus remains present in the Great Lakes ecosystem, potentially affecting fish population dynamics in ways scientists are still working to understand.

Botulism Outbreaks: The Deadly Chain Reaction

A complex ecological chain reaction involving invasive species, changing water conditions, and a naturally occurring toxin has led to recurring botulism outbreaks that have killed tens of thousands of birds along Great Lakes shorelines. Type E botulism, produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, thrives in the oxygen-poor, nutrient-rich environments created by decaying algae on lake bottoms. The toxin enters the food web when invasive quagga mussels filter feed and concentrate the toxin, which is then consumed by round gobies (another invasive species) that feed on the mussels. Birds that eat the infected gobies, including common loons, mergansers, and threatened species like the piping plover, become paralyzed by the potent neurotoxin and typically drown or suffocate.

The scale of these die-offs has been alarming, with over 80,000 bird deaths attributed to botulism outbreaks since 1999. Lake Michigan’s Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore has been particularly hard-hit, with thousands of bird carcasses washing ashore during outbreak years. The problem illustrates how thoroughly invasive species have altered Great Lakes ecosystems, creating new pathways for natural toxins to move through the food web. Climate change may be exacerbating the situation, as warmer water temperatures and lower lake levels create conditions favorable for botulism toxin production. Monitoring programs now track bird mortalities along shorelines, providing early warning of outbreaks and helping researchers better understand this complex ecological threat.

Nuclear Legacy: Radioactive Materials in the Lakes

The Great Lakes region’s role in nuclear research, power generation, and weapons production has left a radioactive legacy in the waters and sediments of these vast freshwater seas. During the Cold War, facilities like the Palisades Nuclear Plant in Michigan, the West Valley Reprocessing Plant in New York, and the Bruce Nuclear Generating Station in Ontario (the world’s largest operating nuclear power plant) released low levels of radioactive materials into the lakes. While most releases were within permitted limits, accidents and poor waste management practices at some facilities resulted in contamination hotspots, particularly in harbors and near-shore sediments.

Radioactive isotopes including strontium-90, cesium-137, and plutonium-239 have been detected in Great Lakes sediments, with the highest concentrations generally found in Lake Ontario, which receives water flowing from the other four lakes. Though levels in open waters are typically below those considered harmful to human health, some fish and bottom-dwelling organisms show bioaccumulation of these materials. The half-lives of some of these isotopes range from decades to thousands of years, making them persistent concerns. Additionally, 38 nuclear facilities (both active and decommissioned) around the Great Lakes basin have proposed or are operating facilities for long-term storage of nuclear waste near shorelines, raising concerns about potential future contamination should storage systems fail over their millennia-long service lives.

The Enigmatic “Lake Michigan Triangle”

Among the more mysterious phenomena associated with the Great Lakes is the so-called “Lake Michigan Triangle,” an area roughly bounded by Manitowoc, Wisconsin; Ludington, Michigan; and Benton Harbor, Michigan. Similar to the more famous Bermuda Triangle, this region has developed a reputation for unexplained disappearances of ships and aircraft, magnetic anomalies, and reported UFO sightings. The legend began with the disappearance of the schooner Thomas Hume in 1891, which vanished with its entire crew during a routine lumber run across Lake Michigan, leaving no trace despite calm weather conditions.

Other incidents have fueled the Triangle’s mysterious reputation, including the strange case of Captain George R. Donner, who disappeared from his locked cabin aboard the freighter O.M. McFarland in 1937 while the vessel was passing through the triangle area. In 1950, Northwest Airlines Flight 2501 crashed into Lake Michigan within the triangle with 58 people aboard, with the wreckage never recovered despite being one of the deadliest commercial aviation disasters of its time. While scientists attribute most disappearances to the lake’s notoriously unpredictable weather, powerful currents, and sudden squalls rather than supernatural forces, the Triangle continues to intrigue both folklore enthusiasts and those studying the many shipwrecks in this particularly hazardous section of Lake Michigan.

Protecting the Great Lakes: Challenges and Hope

The diverse array of threats lurking in the Great Lakes presents unprecedented challenges for conservation and management efforts. Since 2010, the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative has invested over $3.8 billion in projects targeting invasive species, habitat restoration, toxics cleanup, and nonpoint source pollution reduction. This collaborative effort involving federal, state, provincial, tribal, and local governments has achieved significant successes, including the remediation of 11 contaminated “Areas of Concern” and the treatment of over 250,000 acres to control invasive species. The 2012 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement between the United States and Canada created a framework for binational cooperation, establishing shared objectives and accountability measures to protect and restore the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the waters. Under this agreement, the two nations committed to addressing emerging threats such as climate change, harmful algal blooms, and microplastic pollution, while continuing progress on legacy issues like industrial contamination and habitat degradation. The agreement also emphasized science-based decision-making, public engagement, and regular reporting to ensure transparency and sustained momentum in preserving the health of the Great Lakes ecosystem for future generations.

- What Time of Year Snakes Are Most Active in the US? - August 20, 2025

- What a Horse’s Ears Say About Their Mood - August 20, 2025

- The Long Road to Reintroducing Grizzly Bears in Washington - August 20, 2025