Nature has evolved remarkable defense mechanisms across the animal kingdom, with some of the most impressive being creatures that carry their own armor. From thick plates to spiny exteriors, these natural defense systems provide protection against predators and harsh environments. Here’s an exploration of ten fascinating armor-bearing creatures that showcase nature’s ingenuity in defensive adaptations.

Armadillos The Living Tanks

Armadillos are perhaps the most iconic armored mammals, sporting a distinctive shell made of bony plates covered by hardened skin. This armor, called a carapace, is actually composed of dermal bone covered by keratinized epidermal scales. The nine-banded armadillo, the most widespread species, has approximately 2,500 scales covering its body. What makes their armor particularly remarkable is its flexibility—the bands allow the armadillo to move comfortably while maintaining protection. When threatened, some species can roll into a protective ball, presenting only their armored exterior to predators. This evolutionary adaptation has been so successful that armadillos have existed for roughly 55 million years, with their basic body plan remaining largely unchanged.

Pangolins The Walking Pinecones

Pangolins possess one of the most distinctive armor systems in the animal kingdom, with overlapping scales that cover their entire body except for their soft underside and face. These scales, which account for approximately 20% of a pangolin’s total body weight, are made of keratin—the same material as human fingernails. Each scale is incredibly strong yet lightweight, growing throughout the pangolin’s life and constantly being worn down through use. When threatened, pangolins curl into a tight ball, using their sharp-edged scales as weapons against predators. Their armor is so effective that even lions and tigers struggle to penetrate it. Unfortunately, these scales have made pangolins the world’s most trafficked mammals, as they’re prized in traditional medicine despite having no proven medicinal properties.

Turtles and Tortoises Nature’s Shield Bearers

The iconic shells of turtles and tortoises represent one of evolution’s most successful armor designs, having remained fundamentally unchanged for over 200 million years. Unlike what many people believe, a turtle cannot “leave” its shell—it’s fused to the animal’s skeleton, consisting of over 50 bones including the ribcage and spine. The shell has two main parts: the carapace (upper shell) and plastron (lower shell), connected by bridges on each side. This remarkable structure not only provides protection but also serves other functions like calcium storage and acid-base balance. Different species have evolved variations on this basic design, from the soft, leathery shells of sea turtles that improve swimming efficiency to the high-domed shells of desert tortoises that help regulate temperature and store water. Some species, like the box turtle, can even close their shells completely, sealing themselves inside when threatened.

Rhinoceros Beetles The Armored Giants of the Insect World

Rhinoceros beetles sport some of the most impressive armor in the insect world, with an exoskeleton so tough it can withstand forces 30,000 times their body weight. These beetles, which can grow up to 6 inches long, possess a chitinous exoskeleton that serves as both skeletal support and protective armor. Their most distinctive features are the large horns protruding from the head and thorax, which males use in combat during mating seasons. These horns, despite their imposing appearance, are actually hollow and lightweight, allowing the beetles to maintain mobility. The beetles’ exoskeleton also contains layers of specialized proteins and minerals that create a composite material similar in principle to modern body armor. This remarkable defense system makes rhinoceros beetles nearly impervious to most predators, with the additional benefit of preventing water loss in dry environments.

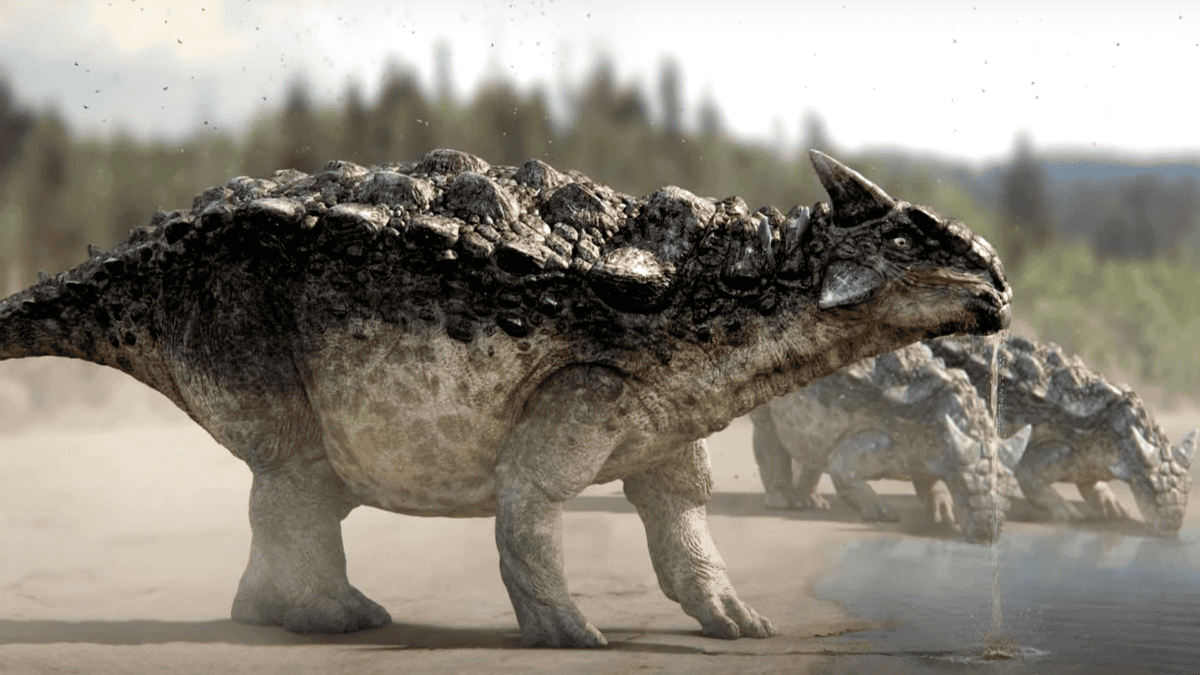

Ankylosaurs The Ancient Armored Dinosaurs

While extinct for approximately 66 million years, ankylosaurs deserve mention as bearers of some of the most extensive armor ever evolved. These dinosaurs, whose name literally means “fused lizard,” had bodies covered in osteoderms—bony plates embedded in their skin. These plates varied in size and shape across different species, forming a mosaic-like armor that protected them from predators like Tyrannosaurus rex. The largest plates could be over a foot in diameter and several inches thick. Most spectacular was the ankylosaurus’ tail club, a massive bony knob that could be swung with devastating force against attackers. Fossil evidence suggests these tail clubs could break bones, making ankylosaurs not just well-defended but actively dangerous to potential predators. This extensive armor came at the cost of speed and agility, with ankylosaurs being relatively slow-moving herbivores that relied on their defensive adaptations rather than flight when confronted with danger.

Thorny Devil The Desert Fortress

The thorny devil (Moloch horridus) of central Australia sports one of the most visually intimidating armor systems in the reptile world. This small lizard, rarely exceeding 8 inches in length, is covered in dense, sharp spines that make it appear much larger and more threatening to potential predators. These conical spines, which cover nearly every surface of the body including a prominent “false head” on its neck, are modified scales that serve multiple functions beyond defense. The spines create a microhabitat of shade on the lizard’s skin, helping to regulate temperature in the harsh desert environment. Perhaps most remarkably, they form a network of microscopic channels that can collect water through capillary action—when morning dew forms on the spines, it’s channeled directly to the lizard’s mouth, allowing it to drink without moving. This multi-functional armor demonstrates how defensive adaptations can evolve additional purposes in challenging environments.

Porcupines The Living Pincushions

Porcupines possess perhaps the most proactive armor system in the mammal world, with up to 30,000 modified hairs that have evolved into defensive quills. These quills, which can be up to 12 inches long in some species, are actually hollow hairs filled with a spongy core and covered in overlapping barbs or scales. When threatened, porcupines can erect these quills using specialized muscles beneath the skin, making themselves appear larger and more imposing. Contrary to popular belief, porcupines cannot “shoot” their quills—but they don’t need to. The quills detach easily when they penetrate an attacker’s skin, and their microscopic barbs make them extremely difficult to remove, working deeper into tissue with movement. In North American porcupines, these barbs are so efficient that the quills can migrate several inches deeper into a predator’s body within days. This defensive strategy is so effective that porcupines confidently waddle through their habitats with little fear, even from predators like mountain lions or wolves that quickly learn to avoid these walking pincushions.

Crocodilians The Living Fossils with Bony Shields

Crocodiles, alligators, and their relatives possess one of the oldest armor designs still in use today, having remained essentially unchanged for over 80 million years. Their protective system consists of osteoderms—bony deposits embedded within the tough, leathery skin. These osteoderms form rows along the back and neck, creating a flexible yet highly resistant shield. On a crocodile’s back, these bony plates are arranged in neat rows, while on the neck they form more irregular patterns for greater flexibility. Each osteoderm has a honeycomb-like internal structure that provides strength while minimizing weight. The gaps between the plates allow for movement and flexibility while still providing protection against bites from rivals or other predators. This armor is complemented by the crocodilian’s famously tough hide, which can be up to 4 inches thick and contains dense collagen fibers arranged in a cross-weaved pattern similar to modern ballistic fabrics. Together, these adaptations make adult crocodilians virtually impervious to predation, contributing to their status as apex predators and their evolutionary longevity.

Trilobites The Armored Pioneers

Though extinct for over 250 million years, trilobites were among Earth’s earliest masters of armored defense. These marine arthropods, which dominated the oceans for nearly 300 million years, possessed an exoskeleton made of calcite—a mineral form of calcium carbonate that provided exceptional protection. Their three-lobed bodies (which gave them their name) were covered by this mineralized armor, with the head shield (cephalon), thorax segments, and tail shield (pygidium) all encased in protective plating. Many species could roll into a ball when threatened, like modern pill bugs, presenting only their armored exterior to predators. What made trilobite armor remarkable was its sophisticated structure—the exoskeleton consisted of multiple layers, including a thin outer layer and a thicker prismatic layer with calcite crystals arranged perpendicular to the surface for maximum strength. Some species even developed elaborate spines and protrusions that provided additional defense. Perhaps most impressive is that trilobites possessed compound eyes protected by lenses made of clear calcite crystal—essentially wearing protective goggles as part of their natural armor.

Glyptodonts The Car-Sized Armored Mammals

Glyptodonts were prehistoric mammals that took armored defense to an extreme, evolving a shell similar to modern armadillos but on a much grander scale. These Ice Age giants, which went extinct roughly 10,000 years ago, could grow to the size of a Volkswagen Beetle, with some species weighing up to 2 tons. Their dome-shaped carapace consisted of more than 1,000 bone tiles (osteoderms) fused together to form an immobile shield that covered their back and sides. Unlike their modern armadillo relatives, glyptodonts could not roll into a ball—their armor was too rigid and heavy. Instead, some species compensated with additional protection, including a cap of armor on the top of the head and, in some cases, a club-like tail encased in bony rings that could be swung as a weapon. The armor was so heavy—up to an inch thick in places—that glyptodonts had modified vertebrae and pelvic bones fused to their shells to support the weight, essentially wearing their skeleton on the outside. This remarkable defensive adaptation made adult glyptodonts virtually impervious to predators, though it likely contributed to their eventual extinction as they couldn’t adapt quickly enough to changing environments and human hunters.

Pill Bugs Tiny Armored Tanks

Pill bugs, also known as roly-polies or woodlice, may be small but they possess one of the most effective armor systems in the arthropod world. These crustaceans—more closely related to crabs and shrimp than to insects—have bodies covered in overlapping, plate-like segments made of chitin reinforced with calcium carbonate. What makes their armor particularly notable is its functionality: when threatened, pill bugs can roll into a perfect ball (a behavior called conglobation), presenting only their armored exterior to predators and protecting their vulnerable underside and appendages. This defense is so effective that it has evolved independently in various arthropod groups, including ancient trilobites. Pill bugs also use their armor for water conservation, with the overlapping plates helping to maintain humidity around their specialized breathing structures. Despite looking like simple creatures, their exoskeleton contains seven pairs of articulated plates that flex and slide against each other, allowing the perfect spherical shape when rolled up while maintaining mobility when extended—a remarkable feat of natural engineering in a creature often less than half an inch long.

Conclusion: Nature’s Armor Evolutionary Marvels of Defense

The diversity of armored creatures across the animal kingdom demonstrates the remarkable power of evolutionary adaptation. From the massive shells of glyptodonts to the microscopic structures of pill bug exoskeletons, these defensive systems have evolved independently in numerous lineages, showcasing nature’s convergent solutions to the universal challenge of predation. The trade-offs are evident across species—heavier armor typically comes at the cost of agility and energy expenditure, while more flexible systems may offer less complete protection. Many armored species have survived for millions of years with minimal changes to their basic body plans, testament to the effectiveness of their defensive adaptations. As we continue to study these natural armor systems, they increasingly inspire human technological innovations, from medicine to military applications, proving that nature remains our most ingenious engineer.

- The Most Powerful Hurricane to Ever Hit US Shores - August 9, 2025

- 10 Animals That Use Bizarre Survival Tactics - August 9, 2025

- The Most Beautiful Bird Migration Routes Across the US - August 9, 2025