The ocean’s deepest realms harbor some of Earth’s most extraordinary creatures, including sharks that have evolved remarkable adaptations to survive in this challenging environment. Far below the sunlit surface, where darkness reigns supreme and pressure crushes most life forms, these specialized sharks navigate their world through bioluminescence, unique body structures, and hunting strategies unlike anything seen in shallow waters. From species that produce their own light to those with serpentine bodies designed for efficiency in the depths, deep-sea sharks represent some of the most fascinating evolutionary success stories in the animal kingdom. This article explores 18 remarkable deep-sea sharks, many of which remain mysterious even to marine biologists due to the extreme difficulty of studying creatures in such remote habitats.

14. Greenland Shark (Somniosus microcephalus)

The Greenland shark is among the most enigmatic deep-sea predators, living primarily in the cold, dark waters of the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. What makes this shark truly remarkable is its extraordinary longevity—scientists have documented specimens estimated to be 250-500 years old, making them the longest-lived vertebrates on Earth. Growing up to 24 feet in length, these sharks move through the water at an incredibly slow pace of less than 1 mph, earning them the nickname “sleeper sharks.” Despite their sluggish movement, they are effective ambush predators that feed on fish, seals, and even reindeer that have fallen into the water. One of their most unusual adaptations is their tolerance for frigid temperatures, with specialized blood compounds that function as natural antifreeze, allowing them to thrive in waters as cold as 28°F (-2°C).

13. Kitefin Shark (Dalatias licha)

The kitefin shark holds the distinction of being the world’s largest known bioluminescent vertebrate, growing to lengths of nearly 6 feet. This species produces a soft blue-green light across its underside, an adaptation known as counterillumination that helps it remain camouflaged against the faint light filtering down from above. Living at depths between 650 and 6,500 feet, kitefin sharks have large, oval eyes that enhance their vision in the dim depths. Their hunting strategy involves vertical migration—they travel toward shallower waters at night to feed on smaller fish, squid, and other sharks before returning to deeper waters during daylight hours. Scientists have only recently begun to understand the complex chemical mechanisms behind their bioluminescence, which involves specialized light-producing cells called photophores embedded in their skin.

12. Cookiecutter Shark (Isistius brasiliensis)

Few deep-sea sharks have a feeding strategy as bizarre and specialized as the cookiecutter shark. Despite its small size of just 20 inches, this shark is notorious for its parasitic feeding habit—it attaches to larger marine animals like tuna, whales, and even submarines, using its specialized jaws to extract perfect circular plugs of flesh from its victims. The cookiecutter shark features one of the most efficient bioluminescent systems in the ocean, with its entire underside glowing green except for a dark “collar” around its neck. This creates a deceptive silhouette that larger predators mistake for a small fish, luring them close enough for the cookiecutter to strike. Living at depths between 1,000 and 3,000 feet during the day, these sharks undertake nightly vertical migrations to shallower waters where they find their unsuspecting prey. Their name derives from the cookie-cutter-like wounds they leave behind—perfect circles approximately 2 inches in diameter and 2.5 inches deep.

11. Goblin Shark (Mitsukurina owstoni)

Often called a “living fossil,” the goblin shark represents a lineage dating back 125 million years. This deep-sea dweller’s most distinctive feature is its protrusible jaw that can extend rapidly forward to capture prey, somewhat resembling the xenomorphs from the “Alien” movie franchise. The elongated, flattened snout houses specialized sensory organs called ampullae of Lorenzini that detect the electrical fields produced by other animals, allowing the shark to locate prey even in complete darkness. Goblin sharks typically inhabit depths between 890 and 3,150 feet and can grow up to 12 feet in length. Their semi-transparent, pinkish-gray skin lacks the strengthening dermal denticles common to other sharks, reflecting an adaptation to the high-pressure, low-energy environment of the deep sea where robust armor is less necessary than in shallower, more competitive waters. Despite being discovered in 1898, goblin sharks remain rarely encountered, with most scientific knowledge coming from specimens accidentally caught in deep-sea fishing nets.

10. Frilled Shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus)

With a serpentine body and prehistoric appearance, the frilled shark looks more like an eel than a typical shark and represents another “living fossil” that has changed little over millions of years. Named for the frilly appearance of its six gill slits, this species typically grows to about 6.5 feet in length and inhabits depths between 390 and 4,200 feet. The frilled shark’s most remarkable feature may be its unique dentition—each of its 300 trident-shaped teeth functions like backward-facing barbs, ensuring that prey cannot escape once caught. Their hunting strategy involves bending their bodies and striking forward like a snake, engulfing prey whole with their expandable jaws. Research suggests these sharks may use their bioluminescent qualities to lure prey in the darkness, though this behavior has been difficult to study in their natural habitat. With a slow metabolism adapted for the deep sea’s energy-poor environment, frilled sharks can survive long periods without feeding—a crucial adaptation for a predator in an ecosystem where encounters with suitable prey may be infrequent.

9. Velvet Belly Lanternshark (Etmopterus spinax)

The velvet belly lanternshark exemplifies the remarkable bioluminescent adaptations found in deep-sea sharks. Growing to only about 20 inches in length, this small shark compensates for its size with an impressive light show—its belly and flanks are covered with photophores that produce a blue-green glow. Scientists have discovered that this species uses bioluminescence in at least three distinct ways: counterillumination camouflage to hide from predators below, complex light patterns on its flanks for species recognition and communication with potential mates, and specialized glowing spines that may serve as warning signals to predators. Living at depths between 650 and 2,600 feet in the eastern Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea, velvet belly lanternsharks feed primarily on small fish, squid, and crustaceans. Recent research has revealed that their bioluminescence may also play a role in “burglar alarm” defense—when threatened, they can produce bright flashes that might attract larger predators to their attacker, creating an opportunity to escape in the confusion.

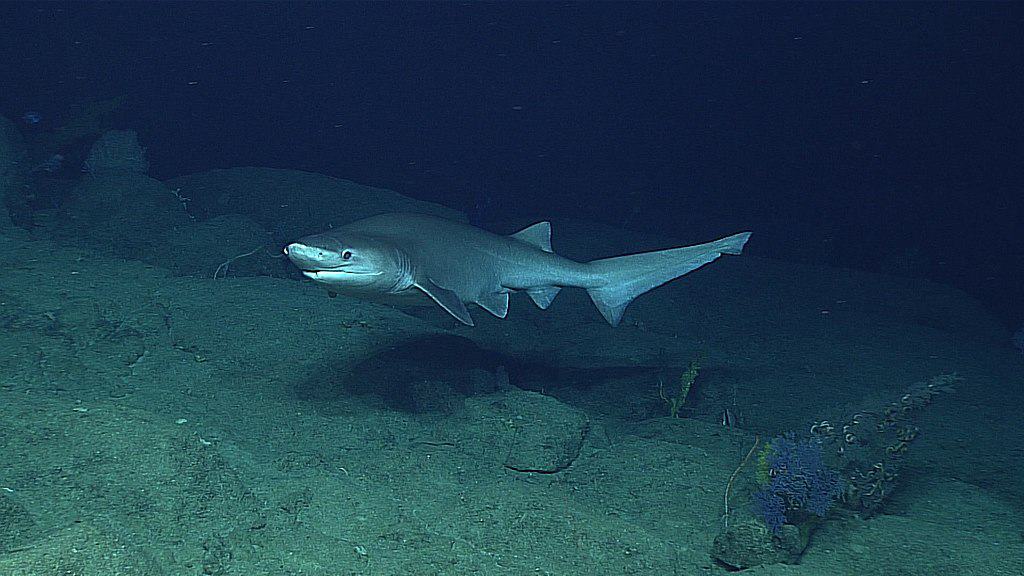

8. Bluntnose Sixgill Shark (Hexanchus griseus)

The bluntnose sixgill shark represents one of the most primitive shark lineages still swimming in our oceans, with fossils of nearly identical ancestors dating back over 200 million years. As its name suggests, this species possesses six gill slits instead of the five found in most modern sharks—a characteristic shared with early shark ancestors. These massive predators can reach lengths of 16 feet and weights exceeding 1,300 pounds, making them one of the largest deep-sea sharks. Inhabiting depths between 300 and 6,500 feet, sixgill sharks are opportunistic predators that feed on a diverse diet including fish, rays, other sharks, seals, and even whale carcasses. Their hunting strategy primarily relies on ambush, with their dark gray coloration providing excellent camouflage in the dim light of their preferred depth range. Unlike many deep-sea species that remain in the abyss permanently, bluntnose sixgill sharks undertake regular vertical migrations, moving to shallower waters at night to feed before returning to depth during daylight hours—a behavior that has allowed scientists somewhat better opportunities to study these otherwise elusive giants.

7. Pacific Sleeper Shark (Somniosus pacificus)

The Pacific sleeper shark, a close relative of the Greenland shark, inhabits the cold, deep waters of the North Pacific Ocean at depths between 6,500 and 6,600 feet. Growing up to 14 feet in length and weighing as much as 1,100 pounds, these massive predators move through the water with surprising stealth despite their size. Their dark coloration provides perfect camouflage in the depths, while their soft, flabby bodies are adaptations to the extreme pressure of their deep-sea habitat. Like their Arctic relatives, Pacific sleeper sharks are exceptionally slow swimmers, typically moving at less than 2 mph—a reflection of the low-energy lifestyle necessitated by the scarcity of food in the deep sea. These sharks have among the lowest body temperatures of any shark species, operating efficiently at temperatures just above freezing. Their diet consists primarily of squid, fish, seals, and occasional scavenging opportunities from whale carcasses. One of their most fascinating adaptations is the presence of parasitic copepods that attach to their corneas, causing partial blindness—a condition that scientists believe may actually help the sharks by making their eyes luminescent, potentially attracting prey in the darkness.

6. Viper Dogfish (Trigonognathus kabeyai)

Discovered relatively recently in 1986 off the coast of Japan, the viper dogfish represents one of the most specialized feeding adaptations among deep-sea sharks. Growing to only about 21 inches in length, this small shark possesses disproportionately large, highly mobile jaws filled with needle-like teeth that can be projected forward to capture prey—an adaptation remarkably similar to that of terrestrial vipers, hence its common name. The viper dogfish inhabits depths between 890 and 1,180 feet and features large, green eyes that provide excellent vision in low-light conditions. Their bodies are covered with photophores that produce bioluminescence, likely serving both as camouflage and to attract prey. What makes this species particularly fascinating is its extreme rarity—fewer than 60 specimens have ever been collected, making it one of the least-studied sharks in the world. Research suggests that viper dogfish undertake daily vertical migrations, moving to shallower waters at night to feed on lanternfish and squid before retreating to deeper waters during daylight hours.

5. Portuguese Dogfish (Centroscymnus coelolepis)

The Portuguese dogfish holds the remarkable distinction of being one of the deepest-dwelling sharks ever documented, with confirmed sightings at depths exceeding 12,000 feet—placing it among the elite group of animals capable of surviving the crushing pressure of the hadal zone. Growing to about 3.5 feet in length, these sharks have adapted to life in the abyss with specialized liver oils that provide both buoyancy and resistance to the extreme pressure. Their bodies are uniformly dark brown to black, with large green eyes adapted for detecting the faintest light signals in their environment. Portuguese dogfish are primarily scavengers, using their acute sense of smell to locate food sources like dead fish and marine mammal carcasses that sink to the ocean floor. Research has shown these sharks possess remarkably slow metabolism and growth rates—a female may not reach sexual maturity until she’s 20 years old, reflecting the energy conservation necessary for survival in the deep sea. Unlike many other deep-sea sharks, Portuguese dogfish give birth to live young rather than laying eggs, with females typically producing 10-14 pups after a gestation period estimated at two years—one of the longest pregnancies in the shark world.

4. Ninja Lanternshark (Etmopterus benchleyi)

Named in 2015, the ninja lanternshark represents one of the most recently discovered deep-sea sharks, found in the deep waters off the Pacific coast of Central America. This diminutive shark, reaching only about 20 inches in length, earned its name from its uniform black coloration that, combined with its bioluminescent capabilities, allows it to seemingly disappear and reappear in the darkness—much like the stealth movements of mythical ninjas. The species name “benchleyi” honors Peter Benchley, author of “Jaws,” who later became a dedicated shark conservationist. Living at depths between 2,700 and 4,700 feet, ninja lanternsharks possess specialized photophores along their belly and flanks that produce a soft blue-green glow, serving the dual purpose of camouflage from predators below and possibly communication with potential mates. What makes this species particularly intriguing to scientists is how its discovery highlights how much remains unknown about deep-sea biodiversity—if a new shark species can be found in relatively accessible waters off Central America in the 21st century, countless others likely remain undiscovered in less-explored regions of the deep ocean.

3. Megamouth Shark (Megachasma pelagios)

The megamouth shark stands as one of the most elusive and mysterious filter-feeding sharks, representing a remarkable example of deep-sea adaptation. Despite reaching lengths of up to 18 feet, this species remained completely unknown to science until 1976, when the first specimen was accidentally caught by a U.S. Navy ship near Hawaii. As its name suggests, the megamouth possesses an enormous mouth lined with rows of tiny teeth and specialized gill rakers that allow it to filter plankton and small fish from the water. Unlike most deep-sea sharks, the megamouth lacks traditional bioluminescence but instead has a reflective white band around its mouth that may attract plankton when it glows from ambient light. These sharks typically inhabit depths between 500 and 3,300 feet during the day, ascending to shallower waters at night to follow the vertical migration of their planktonic prey. With fewer than 100 confirmed sightings since its discovery, the megamouth remains one of the least-understood large marine animals. Research suggests they swim with their huge mouths open, creating a current that draws in water and food—a passive feeding strategy that conserves energy in the food-scarce environment of the deep sea.

2. Deepwater Spiny Dogfish (Centrophorus harrissoni)

The deepwater spiny dogfish inhabits the continental slopes and seamounts of the western Pacific Ocean at depths between 1,000 and 4,000 feet. Growing to about 3.5 feet in length, this shark is characterized by its two prominent dorsal fins, each preceded by a stout venomous spine—a defensive adaptation that provides protection against larger predators in the deep. Unlike many deep-sea sharks that have soft, flabby bodies, the deepwater spiny dogfish maintains a relatively robust musculature, allowing it to be an active hunter of fish, squid, and crustaceans rather than a passive ambush predator. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of this species is its extremely slow reproduction rate—females don’t reach sexual maturity until they’re about 20 years old and produce only 1-2 pups every three years, giving them one of the lowest reproductive rates of any vertebrate. This biological characteristic has made the species extremely vulnerable to overfishing, and it is currently classified as endangered. The deepwater spiny dogfish possesses specialized oil-filled livers that comprise up to 25% of their total body weight, providing both buoyancy and energy reserves in their food-scarce environment.

1. Smalltooth Sand Tiger (Odontaspis ferox)

The smalltooth sand tiger exemplifies the mysterious nature of many deep-sea sharks, inhabiting depths between 30 and 2,700 feet across a remarkably wide but patchy global distribution. Growing to lengths of 11 feet, these sharks are characterized by their long, awl-shaped teeth designed for grasping rather than cutting—an adaptation perfectly suited for capturing the fish and squid that make up the bulk of their diet. Unlike many true deep-sea specialists, smalltooth sand tigers represent transitional species that can be found in both moderately deep coastal waters and the true deep sea, providing scientists with valuable insights into the evolutionary pathways that led to deep-sea specialization. Their reproduction strategy involves intrauterine cannibalism.

Conclusion:

The deep sea remains one of Earth’s final frontiers, and the sharks that dwell within it are living testaments to nature’s capacity for innovation under extreme conditions. These 18 deep-sea sharks—some ancient, some newly discovered—demonstrate a stunning array of adaptations, from bioluminescence and stealthy locomotion to bizarre feeding mechanisms and remarkable longevity. Whether it’s the Greenland shark silently patrolling the Arctic depths for centuries, or the ninja lanternshark vanishing in blackness with a flicker of light, each species reflects a unique solution to surviving in a world of darkness, pressure, and scarcity. Studying them not only enriches our understanding of evolution and biodiversity but also highlights how much of our planet’s life still lies hidden beneath the waves. As technology improves and exploration expands, the mysterious world of deep-sea sharks continues to remind us that science has only begun to scratch the surface of what lurks in the deep.

- The Largest Wildfire to Ever Burn in the US - August 9, 2025

- The Secretary Bird A Raptor That Hunts on Foot - August 9, 2025

- 10 Dog Breed Restrictions That Stir Controversy in U.S. States - August 9, 2025