The jaguar prowled through the spiritual landscapes of Mesoamerica as powerfully as it stalked the physical jungles and forests. For the Maya and Aztec civilizations, this magnificent spotted cat was far more than just an apex predator—it was a divine being, a symbol of power, a cosmic force, and a bridge between worlds. From temple carvings to sacred texts, jaguar imagery permeated these ancient cultures, leaving an indelible mark on their religious beliefs, social hierarchies, and cosmological understanding. The jaguar’s strength, stealth, and nocturnal nature made it the perfect vessel for complex mythological systems that sought to explain the universe and humanity’s place within it. This article explores the fascinating and multifaceted role of the jaguar in Mayan and Aztec mythology, revealing how this magnificent feline shaped two of the most sophisticated civilizations of pre-Columbian America.

The Sacred Feline: Jaguar Symbolism in Mesoamerica

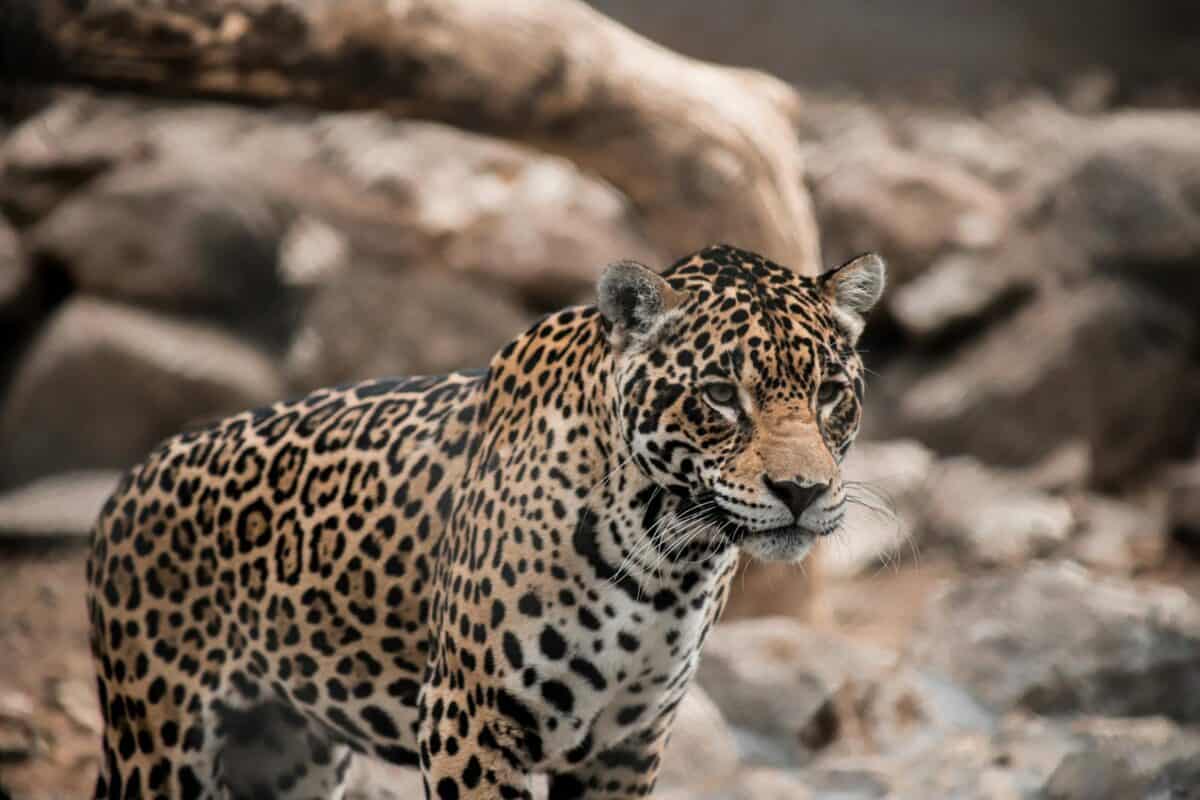

The jaguar (Panthera onca) stands as the largest cat native to the Americas and the third largest in the world. In Mesoamerica, these powerful predators thrived in the diverse habitats ranging from the rainforests of the Yucatan to the highlands of central Mexico. For both Maya and Aztec civilizations, the jaguar embodied raw power, sovereignty, and mystical energy. Its ability to hunt both during day and night, on land and in water, marked it as an extraordinary creature that transcended normal boundaries. The jaguar’s spotted coat, reminiscent of the night sky dotted with stars, further enhanced its cosmic associations. Archaeological evidence shows jaguar imagery dating back to early Olmec times (1200 BCE), establishing a tradition of reverence that would be elaborated upon by later Mesoamerican cultures. The jaguar’s role in mythology wasn’t merely symbolic—it represented a complex set of beliefs about transformation, divinity, and the structure of the universe itself.

The Jaguar Throne: Royal Power and Authority

In both Mayan and Aztec societies, the jaguar was intrinsically connected to concepts of royal power and legitimate authority. Maya rulers often incorporated the jaguar into their royal names and titles, such as “Jaguar Paw” or “Shield Jaguar,” demonstrating their association with the animal’s strength and prestige. Elaborate jaguar thrones have been discovered in various Mayan archaeological sites, including the famous Temple of the Jaguar at Chichen Itza. For the Aztecs, jaguar imagery adorned royal regalia and architectural elements in the imperial capital of Tenochtitlan. The legendary Aztec emperor Moctezuma II reportedly kept a menagerie of jaguars, demonstrating his divine right to rule. The “Jaguar Knights” (cuauhtlocelotl) formed an elite military order within Aztec society, second only to the Eagle Knights in prestige. These warriors wore jaguar pelts and helmets carved to resemble jaguar heads, embodying the ferocity of the animal in battle. Through these associations, the jaguar became a potent symbol of political legitimacy and social stratification in Mesoamerican civilizations.

The Jaguar and the Underworld Journey

Perhaps the most profound mythological role of the jaguar was its association with the underworld and nocturnal realms. In Mayan cosmology, the jaguar was believed to guide the sun through its nightly journey in the underworld (Xibalba), enabling its rebirth each morning. The jaguar’s dark spots against its golden coat symbolized the night sky’s stars against the darkness. In the Popol Vuh, the sacred Mayan creation text, the Hero Twins encounter jaguar deities during their perilous journey through the underworld. For the Aztecs, the jaguar was associated with Tezcatlipoca, the “Smoking Mirror” deity of the night sky, sorcery, and memory. The jaguar’s ability to see in darkness made it the perfect guide through the metaphorical and literal underworld. Archaeological evidence shows numerous jaguar-themed burial items, suggesting the belief that the jaguar would protect and guide the deceased through their afterlife journey. Temple entrances designed as giant jaguar mouths symbolized the threshold between the earthly realm and the underworld, demonstrating the jaguar’s role as a liminal creature capable of traversing cosmic boundaries.

Tepeyollotli: The Jaguar Heart of the Mountain

In Aztec mythology, Tepeyollotli (meaning “Heart of the Mountain”) was a jaguar deity associated with earthquakes, echoes, and the interior of the earth. As one of the manifestations of Tezcatlipoca, Tepeyollotli represented the mysterious forces within the earth’s core. The Aztecs believed that this jaguar god resided inside mountains and that earthquakes were caused by his movements. The jaguar’s roar was thought to be Tepeyollotli’s voice echoing through caves and valleys. In the Aztec calendar, Tepeyollotli ruled over the third day sign, Calli (House), further emphasizing the deity’s connection to enclosed spaces and interior realms. Archaeological evidence includes various stone carvings depicting Tepeyollotli as a jaguar emerging from the mouth of a cave or mountain. The deity’s association with earthquakes highlighted the Aztec understanding of natural phenomena as manifestations of divine will, with the jaguar serving as the perfect embodiment of unpredictable and powerful natural forces. This complex deity illustrates how jaguar symbolism extended beyond simple animal worship to form an intricate part of Aztec cosmological understanding.

The Were-Jaguar: Shamanic Transformation

One of the most fascinating aspects of jaguar mythology in Mesoamerica was the concept of the were-jaguar—humans who could transform into jaguars and vice versa. Shamans and priests in both Maya and Aztec societies were believed to possess this transformative ability, allowing them to access spiritual realms and harness supernatural powers. Through elaborate rituals involving hallucinogenic substances like peyote or sacred mushrooms, these spiritual practitioners would enter altered states of consciousness interpreted as jaguar transformation. The were-jaguar concept appears frequently in Mesoamerican art, depicted as figures with mixed human and feline features—jaguar paws, fangs, or spotted skin on otherwise human forms. These shamanic transformations served multiple purposes: healing the sick, communicating with deities, predicting future events, and ensuring community welfare. The Olmec civilization, predecessors to both Maya and Aztec cultures, produced numerous were-jaguar figurines with infants displaying jaguar-like features, suggesting ancient roots for this belief. This spiritual shapeshifting reinforced the jaguar’s status as a boundary-crosser capable of mediating between the human and divine realms.

Ix Chel and the Jaguar Goddess Connection

In Mayan mythology, the goddess Ix Chel (sometimes spelled Ixchel) maintained strong associations with jaguar symbolism. As a powerful female deity governing medicine, midwifery, weaving, and the moon, Ix Chel was often depicted wearing a skirt adorned with crossed bones and accompanied by a rabbit, one of her sacred animals. In her crone aspect, she appeared as an aged woman with jaguar claws and sometimes jaguar ears, symbolizing her fierce protective nature and connection to the earth’s fertile powers. The jaguar’s association with fertility and birth stemmed from observations of the animal’s reproductive behaviors and its role as a guardian of forest abundance. Archaeological evidence from sites like Cozumel, where a major shrine to Ix Chel existed, reveals numerous jaguar-themed offerings and ceremonial objects. The goddess’s jaguar aspects emphasized the feline’s connection to feminine power, highlighting how jaguar mythology extended beyond masculine warrior symbolism to encompass complex gender dynamics. Through Ix Chel, the jaguar became associated with cycles of creation, destruction, and renewal—much like the waxing and waning of the moon that the goddess controlled.

Balam: The Jaguar Protectors of Maya Communities

In Mayan tradition, jaguars held a special protective role through the Balam spirits. The term “balam” means jaguar in several Mayan languages, and these spiritual entities functioned as guardian deities for communities and agricultural fields. The four Balams were believed to stand at the four cardinal directions, protecting Maya settlements from evil and ensuring agricultural prosperity. This protective function extended into the colonial period, where the Jaguar Gods transformed into the “Bacabs” who continued to serve as community guardians even as Christian influences spread. The Chilam Balam books—post-conquest Mayan texts written in Latin script—preserve many of these jaguar-related protective traditions. These manuscripts, named after the jaguar prophet priests, contain medical knowledge, historical records, and prophecies demonstrating the enduring importance of jaguar symbolism even after Spanish conquest. Archaeological evidence shows jaguar effigies placed at the boundaries of ancient Maya communities, physically manifesting this protective function. The Balam tradition demonstrates how jaguar mythology served practical social functions by reinforcing community identity and providing psychological security against both natural and supernatural threats.

Jaguar Warfare: The Elite Military Orders

The martial prowess of the jaguar inspired elite military orders in both Maya and Aztec societies. For the Aztecs, the Jaguar Knights (Ocelopilli) formed one of the two highest military ranks alongside the Eagle Knights. These warriors earned their position through capturing multiple enemies in battle for sacrifice. Their distinctive jaguar-skin uniforms and wooden helmets carved in jaguar form made them fearsome figures on the battlefield. Archaeological evidence from Tenochtitlan includes stone benches carved with jaguar imagery at the remains of warrior lodges. For the Maya, jaguar warrior imagery appears on numerous murals, including the famous war scenes at Bonampak. These elite warriors utilized the jaguar’s hunting strategies in their military tactics—employing stealth, surprise, and overwhelming force. Military drills and training often incorporated jaguar movements and fighting styles. Beyond practical warfare, these military orders fulfilled ceremonial functions, participating in ritual battles that mirrored cosmic conflicts between light and darkness. The jaguar warrior tradition exemplifies how animal symbolism translated into concrete social institutions that shaped Mesoamerican political and military organization.

The Jaguar in Creation Myths

Jaguars feature prominently in the creation mythology of both Maya and Aztec cultures. In the Popol Vuh, the Mayan creation epic, the first attempt at creating humans resulted in beings who lacked souls and proper respect for the gods—these failed creations were subsequently destroyed, with jaguars serving as divine instruments of punishment. The text describes how “their faces were crushed by things of wood and stone. Their bodies were ground to powder and scattered by the beasts of the forest, among them the jaguar.” This narrative established the jaguar as an agent of divine justice. In Aztec creation myths, the jaguar ruled the Third Sun (Nahui Quiahuitl), one of the five cosmic ages. This era ended when fire rained from the sky, destroying the world, with only those who transformed into jaguars surviving the catastrophe. These creation myths positioned the jaguar at pivotal cosmic moments, emphasizing the animal’s role in both destruction and renewal. Archaeological evidence includes numerous ceramic vessels depicting scenes from these creation narratives, with jaguars prominently featured. Through these origin stories, both cultures explained natural phenomena and established moral frameworks with the jaguar serving as a powerful symbol of cosmic order.

Tezcatlipoca: The Jaguar God of Night and Sorcery

Among the most powerful deities in the Aztec pantheon, Tezcatlipoca (“Smoking Mirror”) maintained strong jaguar associations as lord of the night sky, sorcery, and destiny. As one of the four creator gods, Tezcatlipoca often appeared in jaguar form or with jaguar attributes, including a missing foot replaced by a smoking obsidian mirror—symbolizing his ability to see all things. His nahual, or animal counterpart, was the jaguar, representing his ability to transform and his dominion over darkness. The deity’s connection to jaguars was so strong that one of his calendrical names was Ocelotonatiuh (Jaguar Sun). Archaeological evidence includes numerous obsidian mirrors found in ritual contexts, associated with both jaguar imagery and Tezcatlipoca worship. The ritual calendar featured ceremonies where priests would dress as Tezcatlipoca in his jaguar aspect, wearing pelts and masks during elaborate processions. Tezcatlipoca’s jaguar nature highlighted the ambivalent attitude toward jaguars in Aztec thought—they were both feared and revered, representing both creative and destructive cosmic forces. This complex deity demonstrates how jaguar symbolism reached the highest levels of Aztec theological thought, influencing their understanding of fate, time, and divine power.

Jaguar Symbolism in Art and Architecture

Jaguar imagery pervades Mesoamerican art and architecture, providing tangible evidence of the animal’s cultural significance. Mayan temples often featured jaguar motifs, with the most famous example being the Temple of the Jaguar at Chichen Itza, where jaguar thrones and relief carvings demonstrate the animal’s association with royal power. The Structure of the Five Stories at Edzna displays prominent jaguar imagery associated with the underworld. Jaguar-themed ceramics were ubiquitous throughout Mesoamerican history, with vessels shaped like jaguars or decorated with jaguar glyphs serving both practical and ceremonial functions. Aztec sculptural traditions include numerous jaguar representations, such as the famous life-sized ceramic jaguar knight found near the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan. Codices from both cultures feature jaguar imagery in their pictorial narratives—the Dresden Codex contains numerous jaguar hieroglyphs, while Aztec manuscripts show jaguar warriors and deities. The Mayan script included a dedicated jaguar glyph (BALAM) that appeared in royal names and religious contexts. Even everyday objects like jewelry, textiles, and household items incorporated jaguar motifs, demonstrating how deeply jaguar symbolism penetrated all aspects of material culture in these societies.

The Jaguar’s Legacy: Cultural Continuity and Modern Significance

Despite the Spanish conquest and centuries of cultural disruption, jaguar symbolism continues to resonate in modern Mesoamerican communities. Contemporary Maya groups in Guatemala, Mexico, and Belize maintain numerous jaguar-related beliefs and practices. In some communities, traditional healers claim to transform into jaguars during shamanic journeys, continuing ancient were-jaguar traditions. Annual festivals in various Indigenous communities feature jaguar dances and ceremonies that blend pre-Columbian elements with Catholic influences. The jaguar maintains its status as a powerful symbol in contemporary Mexican and Central American art, literature, and political imagery. The animal appears in the works of prominent artists like Francisco Toledo and Rufino Tamayo, who draw on ancient jaguar symbolism to express modern indigenous identity. Conservation efforts to protect the now-endangered jaguar often invoke its cultural significance, creating partnerships between environmental organizations and indigenous communities. The jaguar’s continued presence in everything from place names to commercial brands demonstrates its enduring cultural power. This persistence speaks to the remarkable resilience of Mesoamerican cultural traditions and the jaguar’s capacity to adapt its symbolic meanings across changing historical circumstances. As contemporary Maya and Nahua communities navigate the challenges of modernity, the jaguar remains a potent symbol connecting them to their ancestral heritage and cosmological understanding.

Conclusion: The Eternal Jaguar

The jaguar’s profound significance in Mayan and Aztec mythology transcends simple animal worship, revealing sophisticated symbolic systems that connected the natural world with cosmic forces. Through its associations with royalty, warfare, shamanism, and the underworld, the jaguar provided a versatile metaphorical framework that helped these civilizations understand their universe and organize their societies. The remarkable consistency of jaguar symbolism across different Mesoamerican cultures and historical periods testifies to the animal’s powerful grip on the human imagination. Even today, as jaguars face extinction in their natural habitats, their mythological presence remains vibrant in cultural memory, artistic expression, and spiritual practice throughout Mexico and Central America. The jaguar’s journey from the dense jungles of physical reality to the rich symbolic landscapes of Mesoamerican thought offers a window into how human cultures transform their natural environment into meaningful cosmological systems—a process that continues to shape our relationship with the natural world in the present day.

- These Endangered Animals Are Making a Comeback - August 8, 2025

- 11 Most Dangerous National Parks in the US - August 8, 2025

- The Most Dangerous Animal in Texas—It’s Not a Snake - August 8, 2025