In the heart of Pennsylvania’s coal country lies a story of remarkable ecological revival. Once a barren landscape scarred by decades of mining operations, the Hazel Creek Mine has undergone an extraordinary transformation from environmental liability to thriving wildlife sanctuary. Abandoned in 1972 after nearly a century of coal extraction, this 2,800-acre former industrial site now teems with diverse ecosystems and serves as a powerful testament to nature’s resilience when given the opportunity to heal. The mine that once symbolized environmental degradation has become an unexpected conservation success story, demonstrating how even our most damaged landscapes can return to ecological productivity with time and appropriate management strategies.

A Century of Extraction: The Mine’s Industrial Past

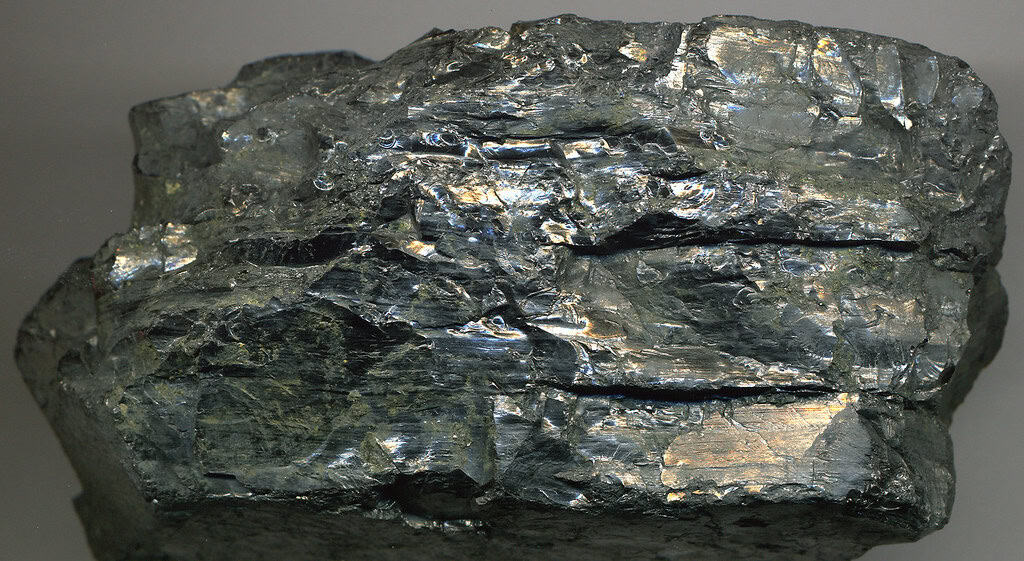

The Hazel Creek Mine began operations in 1879 during America’s industrial revolution when coal powered the nation’s rapid growth. For 93 years, the site was excavated for its rich anthracite coal deposits, creating a vast network of underground tunnels extending more than 300 miles beneath the surface. At its peak in the 1940s, over 1,200 miners worked around the clock, extracting approximately 2 million tons of coal annually. The operation left behind a severely altered landscape: acid mine drainage poisoned local waterways, massive waste rock piles towered over the terrain, and the topsoil was stripped away, leaving behind an environment seemingly incapable of supporting life. When the mining company declared bankruptcy and abandoned the site in 1972, few could have imagined the ecological renaissance that would eventually take place.

Environmental Devastation and Ecological Challenges

When mining operations ceased, Hazel Creek represented a textbook case of environmental devastation. Soil tests revealed toxic levels of heavy metals including lead, arsenic, and mercury. The land’s pH levels were dangerously acidic, measuring between 2.5 and 3.0 in many areas—comparable to vinegar. Groundwater contaminated with acid mine drainage flowed into the nearby Susquehanna River watershed, creating lifeless “yellow boy” streams characterized by their distinctive orange-yellow sediment composed of iron hydroxide. Wildlife was virtually non-existent, with vegetation limited to a few species of acid-tolerant fungi and bacteria. Environmental scientists who assessed the site in the late 1970s estimated that without intervention, natural recovery could take centuries, if it occurred at all. The Hazel Creek Mine became emblematic of the environmental costs of America’s industrial development.

The Reclamation Initiative: From Liability to Opportunity

The transformation began in 1985 when a coalition of environmental organizations, government agencies, and academic institutions launched the Hazel Creek Reclamation Project. This pioneering initiative represented one of the most ambitious mine reclamation efforts in American history. The project adopted an innovative approach that went beyond conventional remediation techniques, which typically focused on containing pollution rather than restoring ecosystems.

Instead, the coalition developed a comprehensive 30-year restoration plan that included neutralizing acid mine drainage, reconstructing topsoil, reintroducing native plant species, and creating diverse habitats. The $42 million project was funded through a combination of federal Abandoned Mine Land funds, state environmental grants, and private donations. Unlike many reclamation efforts that aimed simply to stabilize environmental damage, the Hazel Creek initiative explicitly set ecosystem restoration and wildlife habitat creation as primary goals.

Innovative Remediation Technologies and Approaches

The restoration team employed cutting-edge remediation technologies that have since become models for mine reclamation worldwide. Engineers installed a series of passive treatment systems including limestone drains, constructed wetlands, and successive alkalinity-producing systems that naturally neutralized acidic drainage without requiring ongoing maintenance or energy inputs. Microbiologists introduced specialized bacteria capable of metabolizing toxic compounds and accelerating soil formation processes.

In a particularly innovative approach, the team applied a mixture of biochar, composted waste, and mycorrhizal fungi to jumpstart soil development on barren waste rock. Hydrologists redesigned the site’s drainage patterns, creating a series of interconnected ponds and wetlands that both treated contaminated water and created aquatic habitat. Perhaps most remarkably, the project incorporated biomimicry principles—studying how natural systems recover from disturbance and applying those lessons to accelerate the restoration process.

The Return of Plant Life: Creating Habitat Foundations

The first visible signs of recovery appeared in the early 1990s as specially selected pioneer plant species began establishing themselves on the previously barren landscape. Restoration ecologists employed a phased revegetation strategy, beginning with hardy, pollution-tolerant native grasses like switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) and big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) that could stabilize soil and begin building organic matter. As soil conditions improved, teams introduced nitrogen-fixing legumes such as crown vetch and various native wildflowers that added diversity and created pollinator habitat.

By the late 1990s, the first tree seedlings were planted, including acid-tolerant species like black locust, red maple, and eastern white pine. Today, approximately 60% of the site features mature woodland habitat, including sections that have developed into old-growth forest characteristics in remarkably short timeframes. The plant diversity now exceeds 450 native species, including several rare Pennsylvania plants that have found refuge within the former mine’s boundaries.

The Wildlife Renaissance: From Barren Land to Biodiversity Hotspot

The return of wildlife to Hazel Creek represents one of the most dramatic ecological recoveries documented in reclaimed industrial sites. Wildlife biologists first recorded significant animal populations in the mid-1990s, primarily insects and amphibians colonizing the newly created wetland areas. As vegetation matured and habitat complexity increased, mammal species began returning, with white-tailed deer and eastern cottontail rabbits among the first large vertebrates to establish territories.

By the early 2000s, trail cameras documented the presence of black bears, bobcats, and even occasional mountain lions traversing the property. Perhaps most remarkably, the site now hosts 172 species of birds, including several threatened and endangered species like the cerulean warbler and golden-winged warbler that have established breeding populations. The revitalized streams now support 24 fish species, including the eastern brook trout that requires exceptionally clean water—a testament to the successful water quality restoration efforts.

Wetland Wonders: Aquatic Ecosystems Emerge

One of the most ecologically valuable features of the reclaimed Hazel Creek Mine is its network of constructed and naturally forming wetlands. What began as water treatment ponds have evolved into complex marsh ecosystems covering approximately 340 acres. These wetlands provide critical habitat for a remarkable diversity of species, including more than 15 types of amphibians. The American bullfrog, spring peeper, and the threatened eastern hellbender salamander now thrive in waters that were once too toxic to support any life.

The wetlands serve as important stopover points for migratory birds traveling the Atlantic Flyway, with autumn counts documenting over 30,000 waterfowl using the site. Beyond their wildlife value, these wetlands provide essential ecosystem services including flood mitigation, water filtration, and carbon sequestration. Scientists estimate that the Hazel Creek wetlands can store approximately 1.2 million gallons of water per acre, significantly reducing downstream flooding during heavy precipitation events while continuing to filter residual mining contaminants from the watershed.

Rare and Endangered Species Find Refuge

Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the Hazel Creek recovery is its emergence as critical habitat for threatened and endangered wildlife. The site now hosts 14 species listed under the Endangered Species Act, making it one of the most important wildlife refuges in the eastern United States. The Indiana bat, classified as endangered since 1967, has established maternal colonies in the abandoned mine shafts where stable temperatures and high humidity create ideal roosting conditions.

The mine’s diverse topography—featuring a mix of forests, grasslands, wetlands, and rocky outcrops—has created numerous ecological niches that support specialized species with specific habitat requirements. The eastern massasauga rattlesnake, federally listed as threatened, has established a robust population within the property’s grassland-wetland transition zones. Additionally, botanists have documented several endangered plant species thriving on the site, including the northeastern bulrush and the small whorled pogonia orchid, whose presence indicates the remarkable ecological recovery of soil conditions once considered permanently damaged.

Scientific Research and Ecological Monitoring

The Hazel Creek Mine has become a living laboratory for scientific research, hosting more than 40 ongoing ecological studies. Researchers from universities across the country monitor everything from soil microbial communities to large predator behavior patterns. A comprehensive ecological monitoring program tracks key indicators of ecosystem health, creating one of the most detailed long-term datasets on post-industrial ecological recovery available anywhere.

This scientific work has generated more than 85 peer-reviewed publications documenting the site’s transformation and providing valuable insights for future restoration projects. The science conducted at Hazel Creek has revolutionized mine reclamation practices nationally, demonstrating that ecological restoration goals can be achieved even in severely degraded landscapes. Perhaps most impressively, researchers have documented that certain areas within the property now exceed the ecological functionality of comparable undisturbed natural areas, suggesting that carefully designed restoration can sometimes create systems with enhanced resilience and biodiversity.

Educational and Community Engagement

The Hazel Creek Wildlife Haven now serves as a powerful educational resource, welcoming over 15,000 visitors annually through guided tours, educational programs, and research opportunities. A state-of-the-art visitor center opened in 2010 showcases the site’s transformation through interactive exhibits and offers programs for school groups focused on environmental restoration and wildlife conservation. The site has become particularly important for environmental justice education, demonstrating that communities historically impacted by industrial pollution can experience environmental revitalization.

Local residents who once depended on mining for their livelihoods now find employment as tour guides, maintenance personnel, and research assistants. The haven has also become an economic asset to the region, generating approximately $3.2 million annually in ecotourism revenue for the surrounding communities. This economic benefit has helped transform local attitudes toward conservation, with surveys showing that 78% of area residents now consider environmental protection a top priority for regional development.

The Mine’s Remaining Industrial Features

While much of Hazel Creek has returned to a natural state, the restoration plan deliberately preserved certain industrial elements as historical monuments and wildlife habitat. Several mine buildings have been stabilized and repurposed as bat roosts, with specialized entrances designed to accommodate bat flight patterns while preventing human access. The main mining shaft has been secured with a wildlife-friendly gate that allows bats, small mammals, and certain bird species to use the underground spaces while ensuring human safety.

Some of the massive waste rock piles were intentionally left in place and have developed into unique cliff-like habitats that support peregrine falcons and other cliff-dwelling species. These preserved industrial features serve as powerful reminders of the site’s history while simultaneously providing specialized habitat niches that contribute to overall biodiversity. Interpretive trails connect these features, allowing visitors to understand both the environmental costs of past industrial practices and the potential for ecological healing.

Future Conservation Challenges and Opportunities

Despite its remarkable recovery, Hazel Creek still faces ongoing conservation challenges. Certain areas contain persistent heavy metal contamination that will require monitoring for generations. Climate change presents new threats, with projections suggesting the region will experience more extreme precipitation events that could potentially mobilize buried contaminants or stress recovering ecosystems. Invasive species management remains an ongoing concern, with teams actively controlling non-native plants like Japanese stiltgrass and multiflora rose that threaten to displace native vegetation.

The conservation team has developed a forward-looking adaptive management plan that incorporates climate resilience strategies, including establishing wildlife corridors to adjacent natural areas and maintaining genetic diversity within plant populations to enhance adaptive capacity. Looking ahead, the Hazel Creek Wildlife Haven stands as both a conservation triumph and a model for how abandoned industrial sites across America might be reimagined as wildlife sanctuaries and ecological assets rather than perpetual environmental liabilities.

A Testament to Nature’s Resilience and Human Stewardship

The transformation of the Hazel Creek Mine from industrial wasteland to wildlife haven represents one of America’s most inspiring ecological success stories. This remarkable recovery demonstrates that with appropriate intervention, even severely damaged ecosystems can heal and eventually support thriving wildlife communities. The project offers valuable lessons about the integration of scientific knowledge, community involvement, and long-term commitment in ecological restoration efforts.

As thousands of abandoned mines remain scattered across the American landscape, Hazel Creek stands as powerful evidence that these environmental liabilities can become conservation assets with vision and dedicated stewardship. Through this extraordinary recovery, we are reminded that nature’s resilience, when supported by human care and scientific understanding, can transform our most damaged landscapes into places of remarkable ecological value and beauty.

- The Largest Wolf Ever Recorded Was the Size of a Pony - August 22, 2025

- This Bird Has the Largest Wingspan of Any Living Creature - August 22, 2025

- The Brightest Supernova Ever Recorded Is Visible Again - August 22, 2025