The bald eagle, America’s national bird and a powerful symbol of freedom and strength, faced a catastrophic decline during the mid-20th century that brought it to the brink of extinction in the contiguous United States. By the early 1960s, fewer than 500 nesting pairs remained in the lower 48 states—a devastating reduction from the estimated 100,000 nesting pairs that soared through American skies in the late 1700s. This dramatic population collapse wasn’t the result of habitat loss or hunting alone, but primarily stemmed from a single chemical compound that infiltrated ecosystems across the nation: dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT.

What made this situation particularly tragic was that DDT’s devastating impact on bald eagles and other wildlife came after the chemical had been hailed as a miracle solution for controlling disease-carrying and crop-destroying insects. The story of how this pesticide nearly eliminated one of America’s most iconic species reveals the complex and often unforeseen consequences of chemical interventions in natural ecosystems—and stands as one of the most important environmental lessons of the modern era.

The Introduction of DDT: A “Miracle” Pesticide

DDT first emerged on the world stage during World War II as a revolutionary insecticide. Developed by Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller in 1939, the compound proved remarkably effective at killing mosquitoes, lice, and other disease-carrying insects. Its deployment in war zones dramatically reduced cases of malaria, typhus, and other insect-borne diseases among troops and civilian populations. Müller would later receive the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1948 for discovering DDT’s insecticidal properties—a testament to how beneficial the chemical initially appeared to be for human health.

Following the war, DDT was quickly adopted for civilian use across America. By the late 1940s, farmers were spraying millions of pounds annually on crops to control agricultural pests, while public health departments fogged neighborhoods to reduce mosquito populations. The chemical was considered so safe that promotional videos showed people eating DDT to demonstrate its supposed harmlessness to humans. Between 1940 and 1972, approximately 1.35 billion pounds of DDT were applied in the United States alone, with the chemical becoming ubiquitous throughout American landscapes and waterways.

How DDT Enters the Ecosystem

DDT’s pathway into ecosystems begins when it’s sprayed on crops, forests, or standing water to control insect populations. Once applied, the chemical doesn’t simply disappear after killing target insects—it persists in the environment for years or even decades due to its chemical stability. When rain falls on treated areas, DDT washes into streams, rivers, and eventually larger bodies of water like lakes and oceans. The compound also attaches readily to soil particles, which can be carried by wind or water to contaminate areas far from the original application sites.

What makes DDT particularly problematic is its high solubility in fats rather than water. This property causes the chemical to accumulate in the fatty tissues of organisms rather than being excreted. Small aquatic organisms like plankton absorb DDT directly from the water, beginning a process called bioaccumulation. As each organism in the food chain consumes contaminated prey, the DDT concentrates further—a process known as biomagnification. By the time the chemical reaches top predators like bald eagles, the concentration can be millions of times higher than in the surrounding environment.

Biomagnification: The Fatal Chain Reaction

The process of biomagnification explains why DDT became so devastatingly effective at targeting predatory birds like bald eagles, despite these birds never being directly exposed to concentrated sprays. When DDT entered aquatic systems, microscopic organisms absorbed small amounts of the chemical. Small fish feeding on these organisms then accumulated higher concentrations in their tissues. As medium-sized fish consumed many smaller fish, the DDT levels increased further. Finally, when bald eagles—which primarily feed on fish—captured their prey, they ingested highly concentrated doses of DDT that had magnified at each step up the food chain.

Studies conducted in the 1960s found that bald eagles could accumulate DDT concentrations up to 10 million times greater than the levels present in the water where their prey lived. A single fish consumed by an eagle might contain more DDT than thousands of gallons of lake water. This extreme concentration meant that even relatively low environmental contamination levels could produce toxic effects in eagles and other apex predators. The biomagnification process essentially transformed a diffuse environmental contaminant into a precision-targeted poison against species at the top of the food web.

Eggshell Thinning: DDT’s Silent Mechanism

The primary way DDT devastated bald eagle populations was through a subtle yet catastrophic effect on their reproduction. When female eagles with DDT in their systems produced eggs, the chemical and its metabolites—particularly DDE (dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene)—interfered with calcium metabolism. This interference prevented proper calcium deposition during eggshell formation, resulting in shells that were 20-50% thinner than normal. These fragile shells often cracked under the weight of incubating parent birds, destroying the developing embryos before they could hatch.

This reproductive failure was particularly insidious because adult eagles appeared healthy and continued normal behaviors like nest-building and mating. However, their population was quietly collapsing because successful reproduction had become nearly impossible in heavily contaminated areas. Research published in the Journal of Applied Ecology found that populations of bald eagles declined precipitously when eggshells thinned by more than 18%—a threshold regularly exceeded in most eagle territories during the DDT era. In some regions, not a single eaglet successfully hatched for years, creating entire “silent generations” that should have been the future of the species.

The Decline in Numbers: A National Crisis

The statistics documenting the bald eagle’s decline tell a stark story of a species rapidly disappearing from American skies. Historical estimates suggest that approximately 300,000-500,000 bald eagles inhabited North America before European colonization, with around 100,000 nesting pairs in what would become the contiguous United States. By 1963, at the height of DDT use, only 417 nesting pairs remained in the lower 48 states—a staggering 99% population reduction. Some states lost their entire breeding eagle populations, with once-common birds becoming locally extinct throughout their traditional ranges.

The decline was particularly severe in the continental United States’ primary eagle strongholds. Florida’s population plummeted from over 1,000 breeding pairs in the 1940s to just 88 by 1970. In the Chesapeake Bay region, where thousands of eagles once thrived in America’s largest estuary, fewer than 60 breeding pairs remained. The Great Lakes region, another historical eagle concentration area, saw populations reduced to just a few dozen pairs. Only Alaska, where DDT use was minimal due to its sparse agricultural activity, maintained healthy eagle populations—underscoring the direct relationship between the chemical’s application and the species’ disappearance.

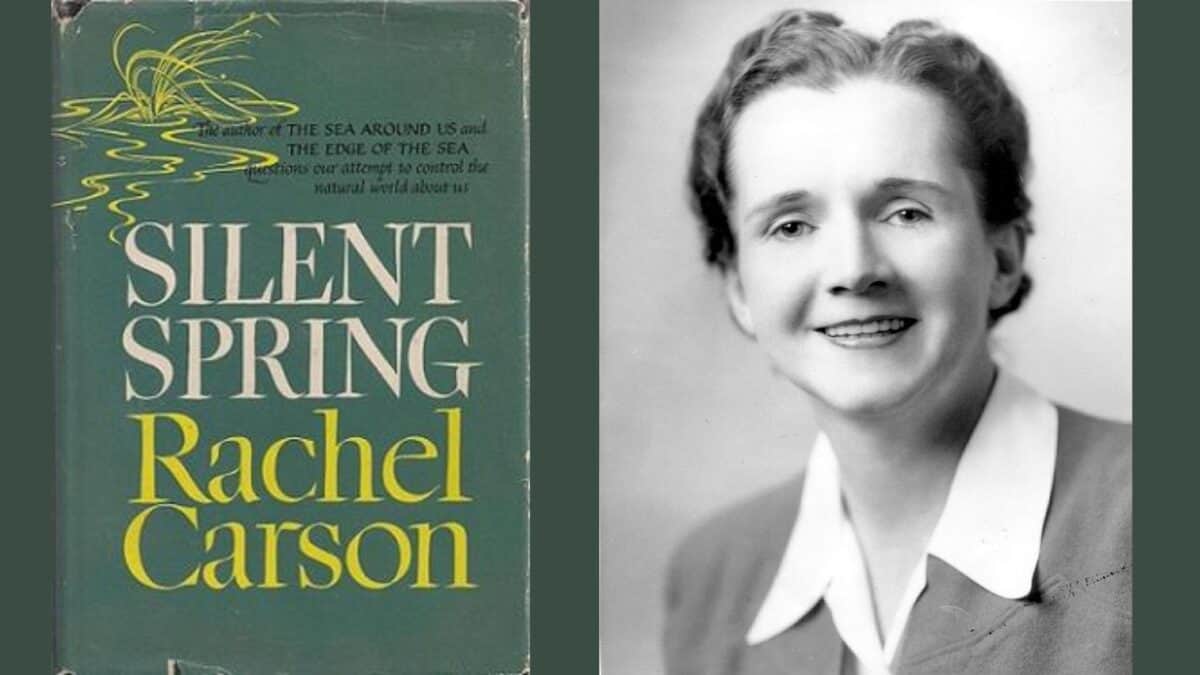

Rachel Carson and “Silent Spring”

The turning point in public awareness about DDT’s devastating ecological impacts came with the 1962 publication of “Silent Spring” by marine biologist and conservationist Rachel Carson. This groundbreaking book meticulously documented how pesticides like DDT moved through food chains and accumulated in wildlife, with particular attention to birds. Carson’s poetic yet scientifically rigorous writing style helped translate complex ecological concepts into terms the general public could understand and care about. The book’s title itself referenced a future where bird songs would be silenced by pesticides—a powerful metaphor that resonated with millions of readers.

“Silent Spring” faced fierce opposition from chemical companies and agricultural interests that benefited from DDT use. Carson was publicly attacked as an alarmist and “hysterical woman,” while chemical industry representatives lobbied aggressively to discredit her research. Despite this backlash—or perhaps because of the attention it generated—the book became a bestseller and catalyzed the modern environmental movement. It prompted President John F. Kennedy to order the Presidential Science Advisory Committee to examine the issues raised in the book, which ultimately validated Carson’s findings and led to the first serious governmental reconsideration of DDT policies.

The Battle for DDT Regulation

Following the scientific validation of DDT’s environmental harms, a complex legal and political battle ensued over the chemical’s regulation. The newly formed Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), established in 1970, began investigating DDT under increasing public pressure. Environmental organizations like the Environmental Defense Fund launched lawsuits challenging DDT’s continued use. These legal challenges forced regulatory agencies to confront the growing scientific evidence of ecological damage while balancing agricultural interests that insisted the chemical was essential for crop protection.

The regulatory process culminated in historic public hearings held by the EPA in 1971-1972, where extensive scientific testimony was presented about DDT’s environmental impacts. After reviewing over 9,000 pages of testimony, EPA Administrator William Ruckelshaus announced a ban on most uses of DDT in the United States effective December 31, 1972. This decision represented a landmark moment in environmental protection—the first time a widely used chemical had been banned primarily for its ecological rather than direct human health impacts. The DDT ban demonstrated that protecting wildlife and ecosystem health could become a legitimate basis for chemical regulation.

International Responses and Continuing DDT Use

While the United States banned most DDT uses in 1972, the international response varied significantly. Some nations quickly followed America’s lead, with Canada and Sweden implementing their own bans. However, many developing countries continued using DDT, particularly for malaria control. This created a complex global situation where eagles and other migratory birds might breed in DDT-free regions but winter in areas where the chemical remained in wide use. Even after the U.S. ban, eagles continued to accumulate DDT during migrations to Latin America, where agricultural use persisted.

The global reckoning with DDT culminated in the 2001 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, which restricted DDT use worldwide except for disease vector control in nations without affordable alternatives. However, this agreement came nearly three decades after the U.S. ban—meaning that for many years, DDT manufactured in the United States was legally exported to countries without similar restrictions. This international regulatory gap meant that global ecosystems continued to receive DDT inputs well into the 21st century, with persistent residues still detectable in remote environments today. Recent studies have found DDT in Arctic ice cores and deep ocean sediments, demonstrating how thoroughly this chemical has penetrated the global environment.

The Slow Road to Recovery

After DDT’s ban in 1972, bald eagle recovery began, but progress was painfully slow. DDT and its breakdown products persisted in ecosystems for decades, continuing to affect reproduction even after new applications ceased. The chemical’s half-life in soil ranges from 2-15 years depending on conditions, but in aquatic sediments—where it most directly enters eagle food chains—degradation occurs even more slowly. Throughout the 1970s, many eagle territories still showed significant eggshell thinning, though the severity gradually decreased as environmental concentrations declined.

Adding to the recovery challenges, bald eagles reproduce slowly even under ideal conditions. They typically don’t reach breeding maturity until age 4-5, produce only 1-3 eggs annually, and don’t always successfully raise all hatched chicks. This reproductive strategy, evolved over millennia to maintain stable populations of long-lived predators, meant that population rebounds would take decades rather than years. Recovery efforts were further complicated by ongoing threats including habitat loss, lead poisoning from hunters’ ammunition, and collisions with power lines. Despite these challenges, eagle numbers began a gradual increase in the late 1970s that accelerated through subsequent decades—a testament to the species’ resilience when given a chance to recover.

Conservation Success: The Eagle’s Return

The bald eagle’s recovery represents one of the greatest conservation success stories in American history. From the nadir of 417 breeding pairs in 1963, the population rebounded to approximately 9,789 breeding pairs by 2006 when the species was removed from the Endangered Species List. Today, estimates suggest over 300,000 individual bald eagles inhabit North America, with more than 70,000 breeding pairs in the United States alone. This remarkable recovery resulted from multiple conservation measures working in concert: the DDT ban, habitat protection under the Endangered Species Act, rehabilitation programs for injured birds, captive breeding initiatives, and intensive nest monitoring.

The species’ comeback has been so successful that eagles have returned to areas where they were absent for generations. They now nest in all 48 continental states, with some urban areas hosting eagles for the first time in a century. The Chesapeake Bay region, which had fewer than 60 breeding pairs in the 1970s, now supports over 2,000. Even heavily developed regions like New Jersey and Massachusetts have growing eagle populations. This recovery demonstrates the remarkable resilience of natural systems when major stressors like DDT are removed, though it’s worth noting that full population restoration took nearly 50 years—a reminder that ecological damage can persist long after harmful practices end.

Lessons Learned: The Legacy of the DDT Crisis

The near-extinction of bald eagles due to DDT fundamentally transformed how we approach environmental protection and chemical regulation. Before this crisis, chemicals were generally assumed safe until proven harmful to humans, with little consideration for ecological impacts. The DDT saga established the principle that environmental persistence and food web accumulation should be key factors in assessing a substance’s safety. This shift in thinking influenced the development of environmental impact assessments that are now standard practice before new chemicals receive approval for widespread use.

The bald eagle’s story also demonstrates the power of scientifically informed activism to effect change. Without Rachel Carson’s pioneering work and the citizen movements it inspired, DDT might have remained in use for decades longer, potentially driving eagles and other sensitive species to extinction. The crisis showed that environmental protection requires both rigorous science and public engagement to translate research findings into effective policy. Perhaps most importantly, the DDT case established that preventing extinction has value beyond practical human benefits—that preserving biodiversity and ecological integrity represents a moral and cultural imperative worth economic sacrifice. This ethical dimension of conservation remains central to environmental debates today, with the bald eagle standing as a powerful symbol of both near-loss and remarkable recovery.

- The Most Remote Lake in the U.S. - August 19, 2025

- 9 Animals That Have an Extra Sense Humans Can’t Even Imagine - August 19, 2025

- 17 Dog Breeds With The Shortest Live Expectancy - August 19, 2025