Born on May 23, 1933, during the depths of the Great Depression, Seabiscuit entered the world with little fanfare at Claiborne Farm in Kentucky. The grandson of the legendary Man o’ War, expectations should have been high for the young colt. However, his early physical appearance did little to suggest future greatness. Small and knobby-kneed with an awkward gait, Seabiscuit was initially dismissed by the racing establishment. His early handlers described him as lazy and uninterested in racing, often preferring to sleep and eat rather than train.

Seabiscuit’s first two years of racing reinforced this assessment. Racing an astonishing 35 times as a two-year-old—a punishing schedule by today’s standards—he managed only 5 wins. Most races saw him finishing in the middle or back of the pack, and his early career trajectory suggested he would become nothing more than a forgettable claiming horse. This inauspicious start made his later transformation all the more remarkable, as the little horse that nobody wanted would eventually become America’s most beloved sports figure during one of the nation’s darkest periods.

The Perfect Storm of Underdogs

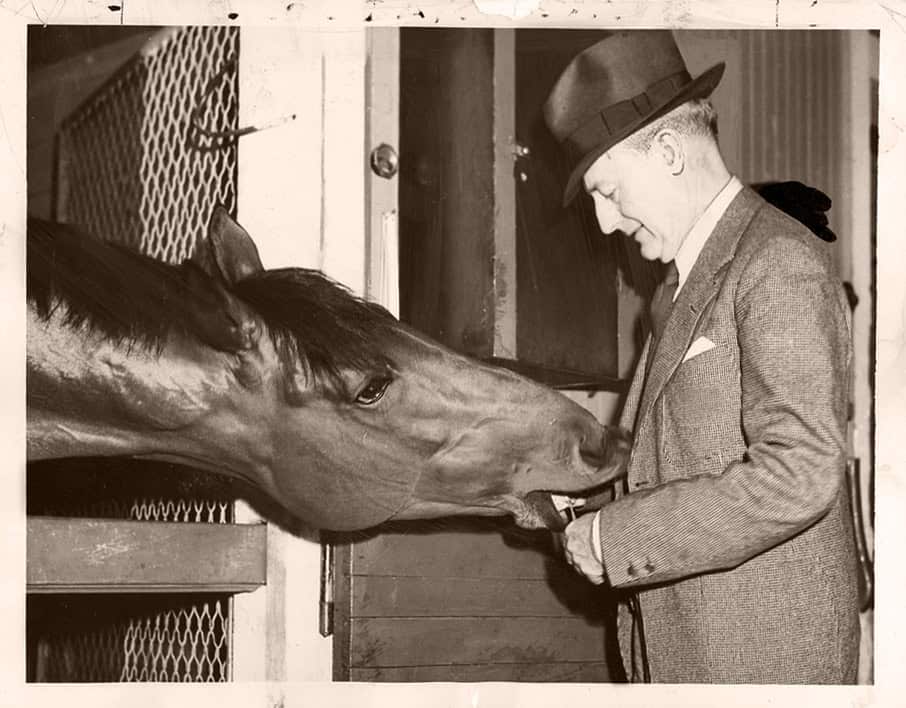

Seabiscuit’s rise to prominence came through his association with three men who, like him, had faced significant setbacks in their lives. Owner Charles Howard had lost his son in a tragic accident and saw his first marriage dissolve under the weight of that grief. Before becoming a successful automobile dealer and businessman, Howard had arrived in California with just 21 cents in his pocket. His interest in horse racing developed relatively late in life, making him an outsider to the established racing world of the East Coast elite.

Trainer Tom Smith was a taciturn frontiersman who had witnessed the closing of the American frontier and lived as something of a nomad before Howard discovered him. Jockey Red Pollard had been abandoned by his family during hard times and raised himself in racing stables, losing sight in one eye from a racing accident—a secret he kept to continue his career. Together, these three broken individuals formed an unlikely team around an equally unlikely horse, creating one of the most compelling underdog stories in American sports history.

The Transformation Under Tom Smith

When Charles Howard purchased Seabiscuit for $8,000 in 1936 at the recommendation of trainer Tom Smith, few could have predicted what would follow. Smith, nicknamed “Silent Tom” for his reclusive nature, saw something in the small, dejected horse that others had missed. He immediately began implementing unconventional training methods tailored specifically to Seabiscuit’s unique personality and needs. Understanding the horse’s intelligence and previous mistreatment, Smith created a nurturing environment where Seabiscuit could thrive both physically and mentally.

Smith’s approach included providing Seabiscuit with companionship in the form of a palomino horse named Pumpkin and a stray dog named Pocatello, who became his constant stable companions. He allowed the horse ample rest and relaxation time, even permitting him to sleep late—unheard of in standard race training. Smith also customized Seabiscuit’s exercise regimen to build confidence and strength without breaking his spirit. The transformation was remarkable: within months, the once-lethargic horse began showing signs of the competitive fire and athletic ability that would soon captivate the nation.

Red Pollard: The Wounded Rider

John “Red” Pollard’s life story paralleled Seabiscuit’s in many ways. Standing at 5’7″—tall for a jockey—and weighing around 115 pounds, Pollard was a hardscrabble boxer-turned-rider whose career had been marked by ups and downs. His most significant secret was his blindness in the right eye, the result of being struck by a rock thrown up by another horse during a race. This disability should have disqualified him from riding, but desperate to continue in his profession, Pollard kept it hidden from racing officials and owners alike.

When Tom Smith paired Pollard with Seabiscuit in 1936, something magical happened between horse and rider. Despite (or perhaps because of) their respective flaws, they developed an intuitive understanding. Pollard seemed to grasp Seabiscuit’s psychology, recognizing the horse’s competitive nature and intelligence. He learned to ride with exceptional tactical awareness, compensating for his visual impairment while playing to Seabiscuit’s strengths. Their partnership, though interrupted by Pollard’s serious injuries during critical points in Seabiscuit’s career, formed the emotional heart of the Seabiscuit phenomenon that would soon sweep America.

Rising to National Prominence

Seabiscuit’s transformation from lackluster claimer to national phenomenon began in earnest during the 1937 racing season. After finding his stride under Smith’s training and Pollard’s riding, Seabiscuit began racking up victories in California. His breakthrough on the national stage came in the February 1937 San Antonio Handicap at Santa Anita Park, where he defeated the highly regarded Rosemont. Though he would lose narrowly to the same horse in the Santa Anita Handicap (known as the “Hundred-Grander” for its unprecedented purse), this race marked Seabiscuit’s arrival as a serious contender.

Throughout 1937, Seabiscuit dominated West Coast racing and then traveled east, where the racing establishment initially dismissed the “western horse.” That skepticism evaporated when Seabiscuit defeated the Triple Crown winner War Admiral’s stablemate Sceneshifter at Suffolk Downs, setting a track record. By year’s end, Seabiscuit had won 11 of his 15 races and was the top money winner in the United States. Despite these accomplishments, he was controversially denied Horse of the Year honors. This slight only added to his growing reputation as the people’s champion—an outsider fighting against the racing establishment, much like many Americans felt they were battling economic forces beyond their control during the Depression.

The Match of the Century

Perhaps no single event cemented Seabiscuit’s legendary status more than his match race against War Admiral on November 1, 1938, at Pimlico Race Course in Baltimore. War Admiral, son of Man o’ War (making him Seabiscuit’s uncle), had won the 1937 Triple Crown and was considered virtually unbeatable. The Eastern racing establishment viewed him as racing royalty, while Seabiscuit represented the scrappy, working-class West. The contrast couldn’t have been more perfect for capturing public imagination: War Admiral was sleek, dark, aristocratic, and traditionally beautiful; Seabiscuit was small, knobby-kneed, and decidedly unorthodox in appearance and running style.

The race, promoted as “The Match of the Century,” captured America’s attention like few sporting events before it. An estimated 40 million people—roughly one-third of America’s population—listened to the radio broadcast. With Red Pollard sidelined by injury, jockey George Woolf took the reins for Seabiscuit. Following Tom Smith’s strategic plan to perfection, Woolf allowed Seabiscuit to look War Admiral in the eye at the start, then burst ahead to an early lead. Though War Admiral caught up and briefly challenged, Seabiscuit found another gear and pulled away to win by four lengths. The victory was more than a sporting triumph; it became a cultural moment that symbolized hope and the triumph of the underdog during the final years of the Great Depression.

Setbacks and Injuries

The story of Seabiscuit would not be complete without acknowledging the remarkable comebacks that punctuated his career. In February 1938, Red Pollard suffered a devastating injury when another horse crashed into him during a training ride, leaving him with shattered ribs and a broken collarbone. This accident forced Pollard to watch from the sidelines as George Woolf rode Seabiscuit in the historic match race against War Admiral. Then, in a cruel twist of fate, just as Seabiscuit was preparing for the 1939 Santa Anita Handicap with Woolf, the horse suffered a ruptured suspensory ligament in his front leg—an injury considered career-ending for most racehorses.

Charles Howard refused to retire his champion, instead sending Seabiscuit to recuperate at his Ridgewood Ranch in California. Coincidentally, Pollard was also recovering there from another serious accident that had broken his leg so badly doctors initially considered amputation. The sight of horse and jockey convalescing together became one of the most poignant chapters in their intertwined story. Against all veterinary advice, Seabiscuit began a slow rehabilitation process under Tom Smith’s careful supervision. Meanwhile, Pollard, using a specially designed cast that would allow him to ride, dreamed of returning to the saddle. Their parallel recoveries reinforced the deep connection between horse and rider that had characterized their relationship from the beginning.

The Comeback at Santa Anita

After more than a year away from racing, Seabiscuit made a tentative return in early 1940 with a few modest races to test his recovered leg. The ultimate goal remained the Santa Anita Handicap—the prestigious race that had twice eluded him by narrow margins. On March 2, 1940, seven-year-old Seabiscuit entered the starting gate for “The Hundred-Grander” one final time. Aboard him was Red Pollard, himself barely recovered and riding with a specially designed boot to accommodate his injured leg. The narrative tension couldn’t have been scripted better: two broken competitors, reunited, facing their greatest challenge together.

Carrying 130 pounds (a significant handicap weight), Seabiscuit broke well but found himself trapped behind a wall of horses entering the homestretch. Pollard, demonstrating remarkable patience and confidence in his mount, waited for an opening. When it appeared, Seabiscuit accelerated with the heart of a champion, surging past the favorite Kayak II (ironically, also owned by Howard and ridden by Woolf) to win by a length and a half. The victory completed one of sports’ greatest comeback stories and provided the storybook ending to Seabiscuit’s career. He had finally conquered the race that had twice denied him, setting a new track record in the process and becoming the leading money winner in racing history at that time with earnings of $437,730.

Cultural Impact During the Depression

Seabiscuit’s rise to fame coincided with some of the darkest years of the Great Depression, and this timing significantly amplified his cultural impact. For millions of Americans struggling with economic hardship, unemployment, and uncertainty, Seabiscuit represented hope and resilience. His transformation from an overlooked, underestimated horse to a national champion resonated deeply with a population that felt similarly marginalized by forces beyond their control. The story of the little horse that refused to be defined by his humble beginnings offered a powerful metaphor for perseverance during difficult times.

Media coverage of Seabiscuit was unprecedented for a sports figure of that era. His races received front-page coverage in newspapers across the country, pushing war news and politics to secondary positions. When he traveled by train, thousands gathered at stations just to catch a glimpse of him. His merchandise—including toys, games, and clothing—sold in quantities that foreshadowed modern sports marketing. The 1938 match race against War Admiral drew an estimated radio audience comparable to that of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats. In a fractured and struggling nation, Seabiscuit became a rare unifying figure, transcending regional, class, and political divisions to become a shared national hero.

Life After Racing

Following his triumphant victory in the 1940 Santa Anita Handicap, Seabiscuit was retired to Charles Howard’s Ridgewood Ranch in Mendocino County, California. The timing proved perfect, as he had achieved everything possible in racing and could retire sound and at the peak of his fame. At Ridgewood, Seabiscuit lived the life of a celebrated retiree. Howard created a special stall for him with a Dutch door that allowed visitors to see the famous horse while protecting his privacy. An estimated 50,000 visitors came to see Seabiscuit during his retirement years, often receiving personally guided tours from Howard himself.

In retirement, Seabiscuit became a successful breeding stallion, siring 108 foals, including Fair Knightess and Sea Swallow, both of whom became stakes winners. While none of his offspring achieved the level of fame or success as their sire, his bloodlines continue in Thoroughbreds to this day. Seabiscuit lived out his days in comfort and dignity at Ridgewood Ranch until his death from a heart attack on May 17, 1947, at the age of 14. He was buried at a secret location on the ranch, marked by a simple stone. Howard, respecting his champion’s dignity even in death, never disclosed the exact location to the public, wanting Seabiscuit to rest undisturbed.

Legacy in American Sports History

Seabiscuit’s impact on American sports and culture has endured long after his death. In 1958, he was inducted into the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame, cementing his place among Thoroughbred racing’s immortals. His story experienced a significant revival in 2001 with the publication of Laura Hillenbrand’s meticulously researched bestseller “Seabiscuit: An American Legend,” which introduced his remarkable saga to a new generation. The book remained on the New York Times bestseller list for two years and was subsequently adapted into an Academy Award-nominated film in 2003, starring Tobey Maguire as Red Pollard and Jeff Bridges as Charles Howard.

Beyond his racing accomplishments, Seabiscuit’s enduring legacy lies in his symbolic value to American culture. He represents the quintessential underdog triumph—a narrative that resonates deeply with American identity and values. His story embodies fundamental national myths about second chances, the irrelevance of origins in determining destiny, and the power of faith and perseverance. Time Magazine included Seabiscuit in its list of the 100 most influential figures of the 20th century, recognizing that his impact transcended sports. Today, Ridgewood Ranch preserves his legacy through tours and educational programs, while the Seabiscuit Heritage Foundation works to protect his bloodlines through descendants of his breeding program. Nearly a century after his birth, Seabiscuit remains one of the most beloved and culturally significant athletes in American history.

Conclusion: More Than Just a Racehorse

Seabiscuit’s journey from overlooked claimer to American icon represents far more than a series of victories on the racetrack. His story embodied the American spirit during one of the nation’s most challenging periods, offering hope when it was desperately needed. The unlikely partnership between a discarded horse, a half-blind jockey, a silent trainer, and a grief-stricken owner created a narrative of redemption and second chances that transcended sports to become a cultural touchstone.

What makes Seabiscuit’s legacy so enduring is how perfectly his story aligns with fundamental American values: the belief that underdogs can triumph through hard work and determination, that past failures need not define future success, and that broken things—be they horses, people, or nations—can be healed and made whole again. In Seabiscuit, America found not just a champion racehorse but a mirror reflecting its highest aspirations and deepest beliefs about itself.

Today, when we recall Seabiscuit as “the little horse that could,” we’re celebrating more than athletic achievement. We’re honoring a symbol of resilience that helped a generation through difficult times and continues to inspire nearly a century later. In the end, Seabiscuit’s greatest victory wasn’t winning the Match of the Century or the Santa Anita Handicap—it was winning the heart of a nation by embodying the power of the indomitable spirit, regardless of the odds stacked against it.

His story reminds us that greatness often comes from the most unexpected sources, and that with the right care, understanding, and opportunity, even the most overlooked among us can achieve extraordinary things. This is Seabiscuit’s true and lasting legacy: not just as one of racing.

- Seabiscuit: The Little Horse That Could Defy the Odds and Inspire a Nation - August 12, 2025

- The Fastest Horse Breeds in the World — Ranked - August 12, 2025

- How Sharks Use Electroreception to Hunt in Murky Water - August 12, 2025