For decades, we’ve imagined dinosaurs as solitary creatures roaming ancient landscapes alone, perhaps meeting only to mate or fight. But compelling evidence is changing this long-held view. Paleontologists now believe many dinosaur species may have been highly social animals that lived, migrated, and even raised their young in complex herds—much like many modern mammals and birds do today. From massive fossil beds containing multiple individuals to trackway evidence showing synchronized movement, the case for dinosaur herding behavior continues to strengthen, offering us a fascinating glimpse into the social dynamics of these prehistoric creatures.

The Revolutionary Fossil Discoveries

The first significant evidence suggesting herd behavior came in the early 20th century, but it was in the 1970s and 1980s when dramatic discoveries began to reshape our understanding. In Montana, paleontologist Jack Horner discovered a massive bone bed containing over 10,000 Maiasaura fossils—adults, juveniles, and hatchlings all preserved together. This wasn’t just a random accumulation of bones. The arrangement suggested these duck-billed dinosaurs lived together in large groups, with apparent “nursery areas” where younger dinosaurs congregated under the protection of adults. Even more compelling, growth rings in the bones indicated these dinosaurs returned to the same nesting grounds year after year, much like modern migratory birds return to specific breeding grounds, suggesting complex social structures that persisted across generations.

Multiple Species, Similar Patterns

What makes the case for herding behavior particularly compelling is that evidence has been found across numerous dinosaur species and families. Ceratopsians like Centrosaurus and Triceratops, sauropods including Diplodocus and Apatosaurus, and numerous hadrosaurs all show evidence of group living. In Alberta, Canada, a bone bed containing over 300 Centrosaurus individuals appears to document a catastrophic flood that caught a herd crossing a river. In China, six perfectly preserved Psittacosaurus specimens were found together in positions suggesting they died suddenly while in a group. These consistent patterns across different dinosaur lineages suggest that herding was not just an isolated adaptation but a widespread and successful survival strategy during the Mesozoic Era, indicating convergent evolution of social behavior across diverse dinosaur groups.

Trackway Evidence: Dinosaurs on the Move

Perhaps even more dramatic than fossil bone beds are the preserved trackways showing multiple dinosaurs walking in the same direction at the same time. In places like Colorado, Wyoming, and Bolivia, paleontologists have discovered extensive dinosaur “highways” with dozens or even hundreds of footprints forming parallel paths. Analysis of these footprints reveals fascinating details—the spacing between individuals remains consistent, suggesting coordinated movement rather than random travel. Some trackways even show larger footprints on the outside of the group with smaller tracks protected inside, hinting at a deliberate protective formation similar to what we see in modern elephants protecting their young. These fossilized moments in time provide perhaps the most direct evidence that dinosaurs coordinated their movements in herds, working together as they traversed ancient landscapes.

Age Segregation Within Herds

One of the most intriguing aspects of dinosaur herding behavior appears to be age segregation within groups. Multiple fossil sites show evidence that juvenile dinosaurs often stayed together in “pods” or subgroups, sometimes with a few adults presumably serving as guardians. This pattern is particularly well-documented among hadrosaurs and some ceratopsians. A remarkable example comes from a site in Argentina where seven Mapusaurus (large carnivorous dinosaurs) of different ages were found together, suggesting even some predatory dinosaurs may have hunted in age-structured groups. This complexity mirrors what we observe in modern elephants, where juveniles are protected within the herd structure, or wildebeest, whose calves gather in nursery groups during migrations. Such age-structured social organization would have provided protection for vulnerable young while allowing them to learn important survival skills from both peers and adults.

The Evolutionary Advantages of Herding

Why would dinosaurs form herds? The evolutionary advantages are numerous and powerful. First and foremost is protection from predators—many eyes watching for danger and many bodies creating confusion for attackers, making it difficult to single out individuals. For herbivorous dinosaurs living alongside fearsome predators like Tyrannosaurus and Allosaurus, safety in numbers would have been critical. Herding also facilitates more efficient foraging, as groups can cover more ground searching for food patches and defend productive feeding areas. For migratory species, collective knowledge about routes to seasonal feeding grounds would be preserved and shared. Perhaps most importantly, herds provide social contexts for mate selection and offspring care, allowing for complex reproductive strategies. These same advantages drive herd formation in modern animals from bison to zebras, suggesting that similar evolutionary pressures shaped dinosaur behavior millions of years earlier.

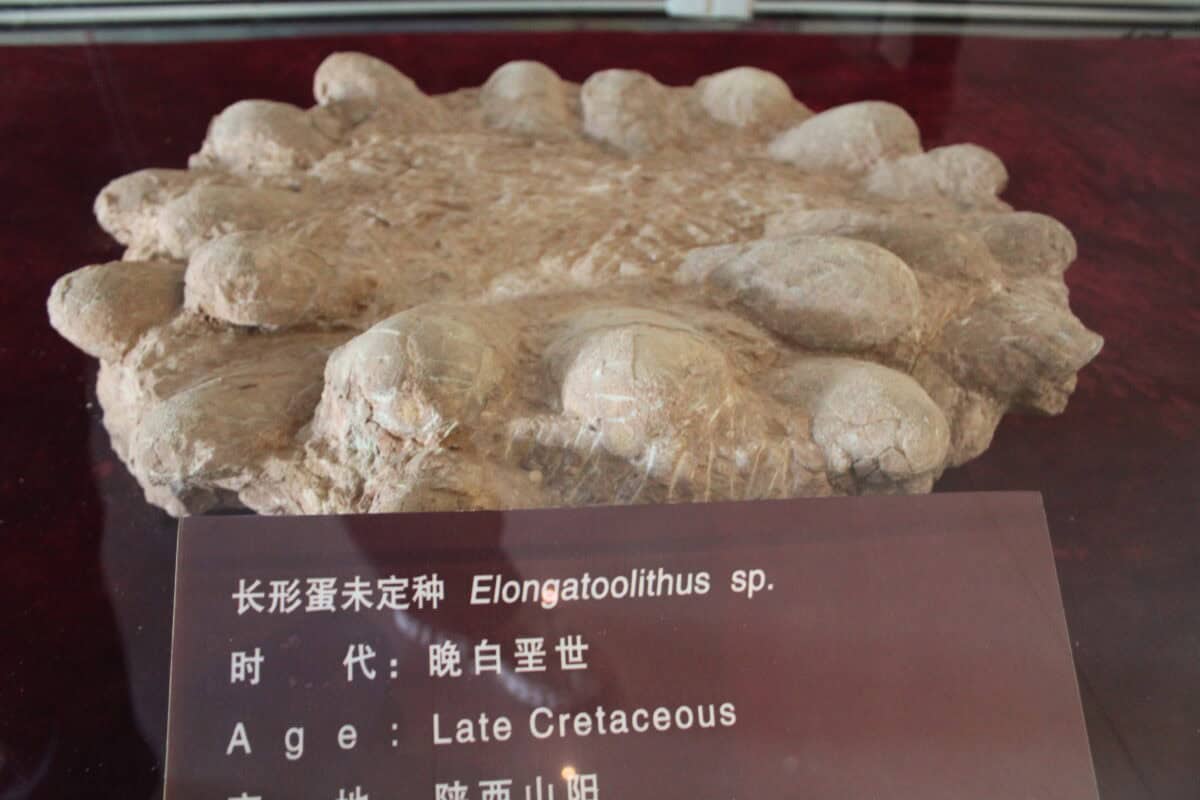

Parental Care: The Foundation of Herd Structure

Strong evidence for parental care in dinosaurs underpins theories about their herd behavior. The Maiasaura (“good mother lizard”) nesting sites discovered by Jack Horner showed nest structures with partially developed hatchlings, indicating parents were providing food to nestbound young. Other discoveries include an adult Oviraptor fossilized while apparently brooding its eggs, similar to modern birds. In Mongolia, a Citipati was found in a protective posture over its nest despite being buried by a sandstorm. These discoveries suggest many dinosaurs invested heavily in their offspring, a prerequisite for the development of complex social groups. The transition from simply laying eggs to actively raising young represents a fundamental shift in reproductive strategy that likely drove the evolution of increasingly sophisticated social structures, forming the foundation for herd behavior that could span generations and involve elaborate socialization of juveniles.

Seasonal Migration Patterns

Isotopic studies of dinosaur teeth and bones have revealed fascinating insights into potential migration patterns that further support the herd hypothesis. By analyzing oxygen and carbon isotope ratios, researchers can determine if dinosaurs moved between different environments seasonally. Studies of hadrosaurs from Alaska show evidence of long-distance migration, potentially traveling hundreds of miles annually between summer and winter feeding grounds. Such long journeys would be much more successfully undertaken as a group rather than individually, providing another compelling reason for herd formation. Seasonal migration in herds would have allowed dinosaurs to exploit different food resources throughout the year, avoid harsh weather conditions, and reach specific breeding grounds—all behaviors we see in migratory herds of modern mammals like caribou. The energetic demands and navigational challenges of migration would have further reinforced social bonds and coordination within dinosaur groups.

Predator Dinosaurs: Group Hunters?

While the evidence for herding is strongest among herbivorous dinosaurs, intriguing findings suggest some predatory dinosaurs may have been social as well. The discovery of multiple Deinonychus skeletons near a single Tenontosaurus victim hints at pack hunting behavior. More dramatically, a site in Alberta, Canada contains the remains of 12 Albertosaurus individuals of different ages, possibly representing a family group or hunting pack that died together in some catastrophic event.

In Argentina, the discovery of multiple Mapusaurus specimens suggests these massive carnivores may have hunted together to bring down the enormous sauropods that shared their environment. Pack hunting would have given predatory dinosaurs a significant advantage when tackling large prey, much as we see with wolves and lions today. However, the evidence remains more circumstantial than for herbivore herding, and some paleontologists remain skeptical about the degree of social coordination among predatory dinosaurs.

Communication Within Dinosaur Herds

For dinosaurs to function effectively in herds, they must have had methods of communication—but what were they? The elaborate crests of hadrosaurs like Parasaurolophus and Corythosaurus likely served as visual identifiers and possibly as resonating chambers for vocalizations that could travel great distances. The frills and horns of ceratopsians may have similarly functioned as visual signals within herds. Studies of dinosaur brain casts show many species had well-developed optic lobes and inner ears, suggesting good vision and hearing that would facilitate group coordination.

Some dinosaurs, particularly ceratopsians, show evidence of potential display structures that changed with age, perhaps indicating status within herds. While we can never know exactly how dinosaurs communicated, the diversity of sensory equipment and potential signaling structures they possessed suggests complex communication systems that would have enabled the coordination necessary for successful herd living across various environments and situations.

Modern Analogues: What Living Animals Tell Us

To better understand dinosaur herd behavior, paleontologists often look to modern animals that occupy similar ecological niches. Elephants provide particularly valuable insights—they’re large herbivores that travel in matriarchal herds with complex social structures and demonstrate remarkable intelligence and social bonding. Birds, as direct dinosaur descendants, offer another window: colonial nesting seabirds show many parallels to the nesting grounds of hadrosaurs and other dinosaurs.

Meanwhile, migrating ungulates like wildebeest demonstrate how large herbivores coordinate movement across vast distances while protecting vulnerable young. Even modern reptiles provide useful comparisons—Komodo dragons, though usually solitary, sometimes feed together on large carcasses in a social hierarchy. By studying how these modern animals negotiate the challenges of social living—from coordinating movement to protecting young and managing resources—we can develop more nuanced hypotheses about how dinosaur herds might have functioned in similar ecological contexts.

Technological Advances Revealing New Evidence

Modern technology is revolutionizing our understanding of dinosaur social behavior. CT scanning allows paleontologists to examine the internal structures of fossils non-destructively, revealing growth patterns that indicate how quickly different species matured—critical information for understanding herd dynamics. Advanced chemical analysis of tooth enamel can now track seasonal movements and dietary changes throughout a dinosaur’s life. Ground-penetrating radar helps locate fossil beds without destructive excavation, leading to more complete picture of how dinosaurs were positioned relative to each other when they died.

Digital modeling of trackways allows researchers to estimate speeds and patterns of movement with unprecedented precision. Perhaps most exciting, machine learning algorithms are now being applied to analyze patterns across hundreds of fossil sites, identifying subtle correlations that human researchers might miss. These technological advances continue to strengthen the case for dinosaur herding behavior while adding nuance to our understanding of how these social structures varied across species and evolved over time.

Debating the Evidence: Scientific Challenges

Despite the growing evidence, some paleontologists remain cautious about interpreting dinosaur social behavior. Taphonomy—the study of how organisms become fossils—reminds us that bone beds can form through processes unrelated to social behavior, such as floods washing multiple carcasses to a single location. Some apparent “herds” might represent individuals gathered at water sources during droughts or seasonal resource concentrations rather than true social groups. Additionally, our tendency to anthropomorphize—projecting human-like social behavior onto animals—can lead to overinterpretation of limited evidence.

There’s also significant variation in the quality of evidence across different dinosaur groups; while the case for herding in certain hadrosaurs and ceratopsians is strong, evidence for other groups remains more circumstantial. These scientific challenges highlight the importance of rigorous methodology and multiple lines of evidence when reconstructing the social lives of animals that lived millions of years ago, ensuring that our conclusions about dinosaur herding behavior rest on solid scientific ground.

Conclusion: Reimagining Dinosaur Social Lives

The evidence for dinosaur herding behavior continues to mount, challenging our traditional image of these ancient creatures as solitary giants. From massive bone beds to parallel trackways, from age-segregated groups to complex nesting sites, multiple lines of evidence suggest many dinosaurs lived rich social lives within structured herds. This evolving understanding transforms how we perceive these animals—not as simple, instinct-driven reptiles, but as complex beings engaging in sophisticated social behaviors that helped them thrive for over 165 million years. As technology advances and new fossils are discovered, our picture of dinosaur herding behavior will undoubtedly become even more detailed and nuanced. Perhaps most profoundly, recognizing the social complexity of dinosaurs helps us understand the deep evolutionary roots of the herd behaviors we see in many modern animals, connecting us to an ancient behavioral heritage that long predates human existence.

- Homeostasis in Animals: Balancing the Internal Environment - August 14, 2025

- The Most Venomous Snakes Slithering Through the Backwoods of Alabama - August 14, 2025

- How Monkeys Are Trained in Certain Cultures—And the Ethics Behind It - August 14, 2025